A conversation with Trevor Strunk, author of Story Mode (part one)

Story Mode: Video Games and the Interplay Between Consoles and Culture is available to purchase now, and so I spoke with its author at length about its messages and theories.

Those of you who listen to the No Cartridge podcast might know that I’m a frequent guest of its host, Trevor Strunk. His book, Story Mode: Video Games and the Interplay Between Consoles and Culture, released in November, so, finally, I have the chance to be the one asking the questions about his projects and thoughts instead of the other way around. It’s truly a fascinating book, and one I recommend to anyone who wants to engage with video games beyond the surface level of just playing them for something to do.

Below is part one of a conversation we’ve been having over email about the book, its themes, and the theories contained within it: there will be a part two at another time, as we wanted to keep the conversation going.

Marc Normandin: We're trying to sell books here, Trevor, so, tell the people about the central idea behind your new book before we get going.

Trevor Strunk: Marc, the central idea behind the book is I need a new addition to my house and a solid gold PS5, so papa needs a cash cow.

No in all seriousness, the book basically is about two things that are interrelated in my mind. The first is the idea of game series — whether that means literal series like Metal Gear Solid or Final Fantasy or sort of spiritual ideas borne out through a genre like survival horror or first-person shooters — and the way they evolve over time. What I noticed was that, while all these series start with a pretty firm trajectory in mind, developers and the game's audience correspond with one another to produce a strange outcome that often is more reactionary than the initial vision, but sometimes also quite a bit more progressive or interesting.

The second thing I ended up tracking, which was a surprise to me while writing, was the way that games were going through this back and forth and growing pains due to the fact that they're evolving as a medium. In this way, game creators are kind of functioning like creators of novels and films and photography before them — they’re experimenting with what it means to produce something that conforms to the medium they've chosen, and therefore also kind of attempting to cement what that medium actually is in the first place. As you can imagine, this involves a lot of growing pains.

MN: Let's talk about what exactly drove you to write this book. Where'd the initial idea for Story Mode come from? What was the genesis of the moment that made you think, "This is a theory that needs to be researched and written, and by me?"

TS: So what's funny is that I think I wouldn't have bothered trying to write a book without my all-star agent Erik Hane, who reached out and asked if maybe I'd like to write something. He'd heard the podcast I do, No Cartridge, and wondered if there was something there I'd like to expand on. We had some fruitful conversation and kind of brought up some ideas which kind of ran their course too quickly and weren't suited for a book, and then I hit upon the idea of working through series.

My initial thesis was that these would end up being depressing but helpful looks at how games just lose their way and become reactionary marketized blobs over time. And honestly I had this idea in mind up until drafting, but as I wrote the book and really sketched out my ideas about these games in more detail, I found that more complex kernel I mentioned above, and I ended up seeing that the book was more about how games exist in their own generative space. In other words, it's not a "games are art" book or a "games are political in this way" book, it's a book that looks at those ideas in a kind of interconnected way, thinking about games as a spectrum of ideas that are influenced in a lot of surprising and often generative ways.

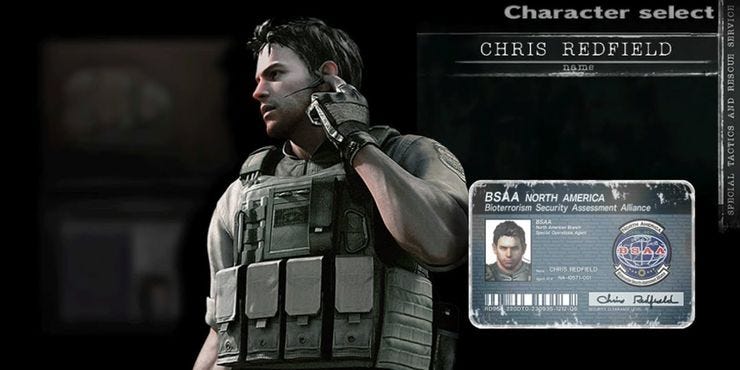

MN: You mentioned that some series can become more "reactionary" over time, which I read as they are reacting to the environment they are placed into and evolving within. I'm curious, though, about your thoughts on video games and a more explicitly political kind of "reactionary." Resident Evil, for instance, had a post-9/11 shift from the kind of horror of isolation and the fear of the unknown that you wrote about in Story Mode, to being more about action and fighting global terrorists as part of elite, above-the-law-ish squads built from the best of the best of the best, yes sir types. The terrorists still ended up, like, transforming into giant goo monsters or what have you, but still, to me this feels like the kind of shift you're making a point of here in terms of games being fed by and simultaneously feeding reality in a loop. (A cultural ouroboros, as it were, which is a joke I'm required to make while referencing anything about Resident Evil 5.) I'm not saying Capcom was personally in favor of the United States invading Afghanistan and Iraq or anything, so much as the audience was there for games pulling from the kind of world that would see America do that. And now the series has shifted back to its more personal and explicit horror roots, as you wrote about in your chapter on horror.

First off, is that a complete misunderstanding of the text — this is going to be a long-ass interview for everyone if so — and second, what do you think might have driven Capcom away from the very explicit "but then the terrorists will win!" plot direction and back to the more personal, individualized horror that launched the franchise to begin with?

TS: Not a misunderstanding at all! Actually, when I used "reactionary" before, I meant it in the political sense — I found that all games are reactive in the first way you lay out, that they're always responding to some sort of dialogue between the creator of the game and the audience for the game. But as you've correctly identified, there's a shift in what I guess we can call a "global unconscious" after 9/11, where suddenly the stuff a mass audience cared about before shifted perceptibly (albeit without any grand statement or anything of the like). I use 9/11 a lot as this sort of shift because — as it does in the first-person shooter and horror chapters — it serves as a neat little dividing line. But unlike shooters, which are still military ooh-rah outside of the more arcade-y return to games like DOOM (2016) or DUSK, horror games definitely push back a bit more against the easy divide.

In part that's because horror games, as I write in the book, are always trying to reverse engineer what their audiences are scared of, even when they don't consciously know they're doing it. If Capcom released Resident Evil and instead of zombies it was, I don't know, a bunch of sentient eggplants wandering the manor, I doubt we'd have the same monolithic horror franchise we have today. That's a silly example I know, but it serves to illustrate the fact that the horror genre absolutely must care about its audience in a way that so many other genres really don't have to, at least not until the game is released and starts getting reviews. As a result, I think the realization that the idea of other people invading begins to ebb after the 2008 financial crisis, at the same point that your average Joe on the street is probably realizing America isn't much of a superpower anymore, because the fear of being overrun or taken over is replaced with a fear of just being irrelevant or unimportant. Alone but not in the sense of being stalked, more in the sense of being forgotten. And so you get Resident Evil 7, notably taking place in the middle of nowhere in a poor, abandoned old manor left to decay. Resident Evil: VIIlage is kind of the same, though it came out too late for me to cover, but you can see how the blueprint is there too.

Ultimately, the idea of letting the bad guys win being the ultimate sin, and the patriotism that drove a country to the brink of supply shortages on hokey flags drives first-person shooters in many ways still because that's the kind of first-person shooter we've manufactured consent for. That they're being challenged at all is kind of remarkable. For horror games, though, that need to keep abreast of the style of existential fear an audience feels is crucial, and I think that's why we're seeing not just indie games but full-fledged AAA games speaking to a kind of personal terror of being alone because you have ceased to matter.

MN: Here I am, concerned I'm shoving my politics into things, but no. It is you who is shoving my politics into things.

Anyway, I wanted to talk about 9/11's role in video games first so we could ease into a real thorny subject: let's switch gears and talk about Difficulty Discourse. You delve into difficulty as aesthetics (and aesthetics as difficulty), centered around the Souls universe of games. I'm with you on it being a tough subject to discuss, since apparently not everyone has read the Dia Lacina feature that you cite on how "difficulty is not synonymous with accessibility," so sometimes the two sides end up talking past each other. So, just focusing on actual difficulty here: Difficulty sliders are wonderful — I believe every game that can do what Mass Effect and its ilk have done, which is to make a more casual mode that lets you enjoy the story and not stress the combat so much, should. Hades' God Mode that lets you make your way through the story a little easier after each failure is also a brilliant innovation, and one I used until everything clicked. Xenoblade Chronicles letting you switch to a casual mode at any time, where enemies go down much faster to alleviate the stress of backtracking and grinding in a JRPG, is incredible. And yet, sometimes, I just want a game to kick my ass and force me to pick myself back up, by myself, as Metroid Dread recently did.

I bring up Dread because it was criticized by some as being poorly designed because of its difficulty, in some corners as significant as the one David Jaffe of God of War and Twisted Metal fame resides in. And to me, there's a significant difference between "game is designed to be a challenge" and "game is a challenge because it's poorly designed." You mention Battletoads in Story Mode as a game whose difficulty no one is going to confuse for an artistic choice — it's very obviously a poor design that expected too much of any player, the kind of thing that would have been too greedily quarter-thirsty for arcades in the 80s. Shoot-em-ups are a wonderful, often difficult genre of games, but there are great shoot-em-up designs that are both difficult and rewarding, and then there are ones where there are checkpoints before the boss of a stage, but after every power-up you could collect, what was the developer even thinking?

Metroid, on the other hand, is closer to the Souls version of challenge and aesthetics you describe: the game works the way it does, narratively and in how it feels to play, because of its difficulty, because of its design choices meant to create tension and confusion. These are intentional decisions, not oversights, that make Metroid what it is. Assuming this kind of intentional difficulty is what we're discussing, what do you think about these dueling desires of balancing Something For Everyone with Everything For Everyone, and where it might lead development in the future?

TS: That's a really good question, and one that I do think ultimately may boil down to "well, not everything is for everyone." But I'm hesitant to say that since it's a bit like giving up — I don't want to admit that my (read: Dia's) version of difficulty crumbles when it's all about some kind of aesthetic choice. I think what's more helpful is to say that something like Dread is closer to a tough novel, something that rewards reading and re-reading to get at the right angles. Really hard games that attempt to make something of their difficulty should work like that, in my opinion: you mentioned design being of paramount importance, and I think you're right, since something like the Souls games or Dread rewards constant failure and learning as the game sort of lets you into its secrets.

Now I realize that kind of recursion isn't for everyone, and there are some people who can't stand the Beckettian die, die again roundabout in FromSoftware’s games or Dread. However, I think there's some truth in the idea that the stories for these games couldn't really be conveyed without that frustration; I don't oppose an easy mode for a Souls game, but imagining that story without the corresponding mechanical trouble is so blank, you know? Like it's a fantastic story, but embodying that story is part and parcel of the telling — your being the chosen undead, with all of their foibles and deaths, is a kind of metaphorical leap to your own standing as a person. To just experience the story in god mode would deaden that a bit.

Now, ultimately, that's more an endorsement for games that are hard but understand their development so well that, given enough time, any gamer could become masters of them. Which is in itself a version of saying "hey man, why don't we just make every game amazing?" But I do think that there's some circles that see difficulty as a sine qua non of gaming as opposed to a very specific choice that requires very careful and intentional and skilled design to get right.

MN: That makes a lot of sense, the idea that difficulty that exists for more than the sake of just the difficulty alone requires skillful design. Given the improvements to the checkpoint system, and that Metroid games instituted a post-game hard mode decades ago, I feel comfortable saying we already have an "easy" mode for Metroid games, and it's the default one. We can allow that distinction to exist because of the kind of intentional, skillful design you cited. Maybe it's not for everyone... but it could be.

I think a lot about Gears of War 2 and its cooperative mode, which managed to seamlessly mesh multiple difficulty levels together. You and a partner would be climbing the same mountain, basically, at the same pace, with the more skilled and/or experienced player's abilities offsetting that their bullets essentially did less damage and that they died much more quickly than that of the player who was on casual, easy, whatever. This kind of mashup also kept the game from being solely the providence of the player who was better at/more experienced at Gears of War 2. Just by nature of how little damage they could take before they needed to be revived, and how many rounds they had to fire in order to take down even basic enemies, the partner playing on the lower difficulties was vital to the experience. They aren't going to use rounds up as quickly, even if they're not as deadly accurate with their weaponry: they're in a better position to save the day through revival, or a chainsaw-bayonet charge to smash through the Locust's lines, meaning they aren't just watching the other mow down the opposition. There are surely players out there who wouldn't have been able to complete Gears 2 on its toughest difficulty without the benefit of a friend playing on a lower difficulty, even. Managing something like that is obviously a challenge, but it was one that Epic's skillful developers were capable of both envisioning and creating. It'd be nice if more games could manage to figure out this balance achieved in an Xbox 360 game from 13 years ago.

If you want to keep pulling on that thread, by all means: I could talk about difficulty and Gears of War 2 all day long. I've got another question for you to ponder, however. Your chapter on Metal Gear and Hideo Kojima is one of the best in the book, in my opinion, especially since, as analyzed as both the works of Kojima and Metal Gear are, as you say in Story Mode, there only seem to be certain ways we're allowed to talk about either of them. It was refreshing to see some different angles from someone who still thinks highly of the franchise as a whole despite the stated issues.

My question here, though, is specifically about Metal Gear Rising Revengeance, which gets just a brief mention in the book. One of the main points you make in your Metal Gear chapter is that the series, its messaging, its focus, all of it changed in between Metal Gear Solids 2 and 3, in a way that corresponds with your theory about this kind of cultural push and pull, give and take on game development and franchise direction. Do you find that Revengeance is somewhat outside of this particular trend, given that it is not only an action game no one was especially asking for, but that it went back to Raiden, who is much-loathed in some circles of the MGS fandom for not being Snake? And that even without the franchise auteur at the helm, managed to force the player to ask themselves questions about what it means to be playing as a video game protagonist responsible for so many, many deaths, and why they get to be the hero in a game where pacifism is not an option?

TS: So first off, to tug at that thread a little bit, I love the point about cooperative gameplay. I don't know why this isn't something that's pursued more often, and I can't pin it down to the death of couch co-op either, as the options for really playing with as opposed to against your friends weren't exactly plentiful then either. Games like Gears 2 or Divinity 2 are few and far between, but almost everyone loves them, so I have to wonder if we're not just spiting ourselves as gamers by not having more of them. Party games and FPS are fun and all, but they can't possibly be the only option, right? Maybe it's a cultural issue wherein we refuse help Horatio Alger style; I'm not sure, but I'm curious to know more.

Anyway, your point on Revengeance is a really good one, and it's one I didn't have enough time to really think about in the book — also my experience with Revengeance isn't quite enough to be authoritative about it, in my opinion. That said, I do think that there's a way that the game does key into the somewhat forgotten arc of Metal Gear Solid 2 by way of the goofy Platinum brand, doing that nice Bayonetta acrobatica whereby we get compelling ideas and extraordinarily lush setpiece action as well. But that may also be a bit of a dodge; the goofiness of the plotline in Revengeance is probably best set against the stodgy and dour plot of MGS4, which Raiden also appears in, along with fellow MGS2 alumnus, Vamp (they call him that because he's bisexual!).

But while MGS4 tells an interesting enough story about aging and obsolescence even in the sort of militaristic heaven that someone like Liquid or Big Boss would want, that's not a particularly new story. It's the death of the old soldier, predating MacArthur and going as far back as Achilles. What Raiden is in MGS2 is the new hero, replacing and not replicating the old hero; the death of merchandising and the rise of replaceability and artificiality as opposed to "genuine" heroes. Of course, this has been the case already in MGS1 and Solid Snake, though particularly via the clone army storyline in the former. The sin MGS2 committed that needed to be corrected by Kojima to retain his audience in MGS3 is openly saying that the hero is not just obsolete, but ultimately modular, able to be slotted in and refitted at will by the state. As we have seen with the UK's horror over a female or Black James Bond, this is a third rail of sorts.

And Revengeance, I think, actually honors this. Raiden is robotic and destroyed — a second Ninja/Gray Wolf perhaps — in MGS4, and he's just as horribly messed up in Revengeance. But he's horribly messed up in a way that is still deeply effective. For all the allure of Snake, he is always efficient as a killer, and to answer the question of "ok what would Raiden be like if he was too" is kind of brilliant. It reveals the grim fantasy beneath complaining about Raiden's emotional approach to the series' protagonist role, the demand for efficient killers that really was what Ocelot wanted all along with the Solid Snake Simulation program we see uncovered in MGS2. Man, what a game that is.

Part two of this conversation will publish at a later date. You can find Story Mode for sale at bookstores and online retailers such as Bookshop.org, listen to past, present, and future episodes of No Cartridge through your podcast app of choice or at No-Cartridge.net, and Trevor Strunk’s promotional materials and good tweets can be found on Twitter at @hegelbon.