This column is “It’s new to me,” in which I’ll play a game I’ve never played before — of which there are still many despite my habits — and then write up my thoughts on the title, hopefully while doing existing fans justice. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

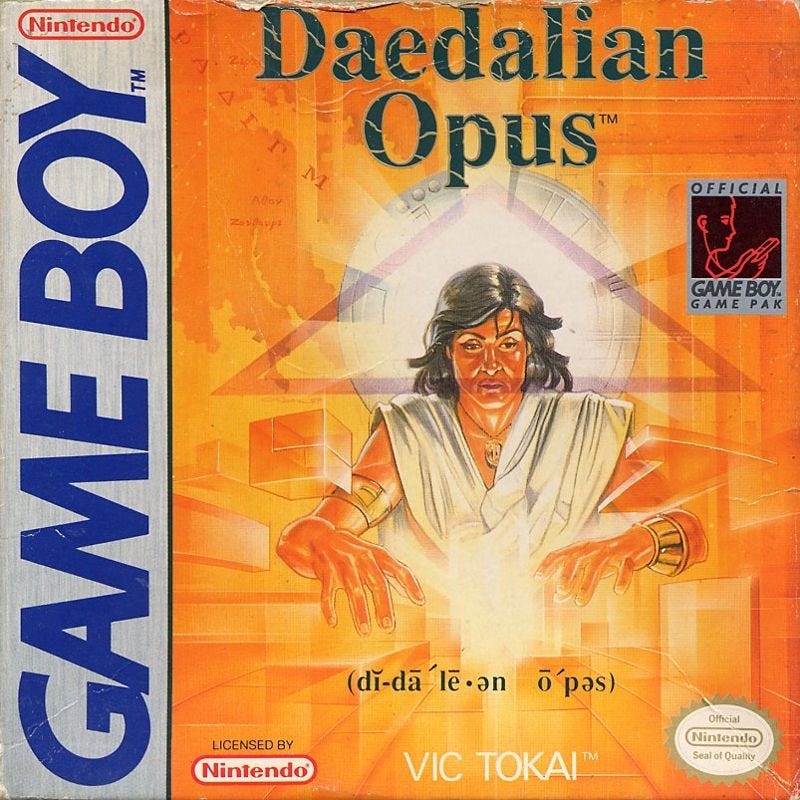

Sometimes I decide to buy or play a game I haven’t played before because I’ve known it existed for a long time, but just hadn’t gotten around to it or had the opportunity or desire to before then. Other times, you see something on the shelf at your local shop with retro games for sale, and you’ve never heard of it, and it costs $3, so you quickly do a search on your phone to see what it even is and then hand a few bucks over to the cashier when you’ve confirmed you probably won’t regret doing that. Daedalian Opus falls into the latter category: even as someone who enjoys Vic Tokai games, I hadn’t ever heard of this Game Boy puzzler before seeing a loose cartridge on the shelf.

Good news, however: I do not miss my $3. Daedalian Opus — named for the mythical Greek architect Daedalus, the creator of King Minos’ labyrinth on the island of Crete — is short, and it lacks features in the way you’d imagine a 1990 Game Boy release might, but it does the one thing it set out to do well, which is to make jigsaw puzzles of increasing size for you to solve that will eventually frustrate you — in a good way — while a clock counts the seconds the entire time. There aren’t rankings or scores or anything, so the clock doesn’t really matter for anything besides your own feelings of adequacy or inadequacy, and yet, you can somehow hear the soundless thing ticking louder and louder in your ear the longer you take to solve the puzzle.

Daedalian Opus starts out easily enough. You have three polyomino pieces to slot in together on a small-ish rectangle board, and once you realize that you can rotate the pieces, flip them horizontally, or flip them vertically, it won’t take very long for you to figure out where those three should go in order to fill the space and complete the puzzle. The size of the puzzles grows each time out, however, and the kinds of polyominoes you are choosing from and placing changes again and again, as well — you will oftentimes unlock a new puzzle piece on your character’s little walk to the next stage, which is also where you receive the password used to save your progress — so it doesn’t take long for Daedalian Opus to become more difficult.

There’s a lot of trial and error to solving the puzzles, which is not meant as a negative. Unless your brain works a certain way, you’re going to have to look at the pieces you have to place, and pick one you think makes sense as a starting block, then place it. Keep doing this until it’s clear you messed up somewhere along the way, then start flipping and rotating and swapping out different pieces. You’ll start to get a sense of which pieces are used for specific purposes, though, which ones are reliable starter pieces, which polyominoes are probably best to save for near the end of the puzzle.

A thing you need to watch out for as the puzzles become more complex is which blocks need to be used at all: you’ll eventually start receiving more pieces than you need to complete the puzzle, which means it’s not just a matter of narrowing down where to place what you’ve got, but also what among the pieces you have needs to be used at all. This isn’t the case at all early, but it doesn’t take too long for the game to start mixing these extra blocks in. There are just 36 levels in Daedalian Opus, starting with the three-piece opener and ending with a whole bunch of 12-block puzzles in increasingly complex shapes and arrangements one after the other.

Given this wasn’t a particularly popular or notable release, there aren’t a ton of walkthroughs for it out there, but a couple do exist, including one visual aid that shows the solution for each of the stages. For our purposes, it’ll give you a sense of how the scale and shape of the puzzles changes as the game progresses, and how many kinds of pieces exist within Daedalian Opus:

In between stages, you take control of a little guy, who you have exit one building with a stage housed within it, and have him cross a bridge to the next one. A little UFO appears and displays a four-letter password that you can use to retain your progress, since Daedalian Opus doesn’t save anything, and you’ll often come into contact with a fairy creature who will grant you access to the next block to be used in future puzzles. This short gameplay video displays pretty much the entire game experience, from the end of one stage to the completion of the next one, as well as three of the six songs that are in the game (with the others being the title screen music and other stage themes):

Now, what’s missing from this video is the wrong guesses — every piece is placed where it belongs here, when it needs to be and where it needs to be — but you can see that there are extra blocks already at this early juncture of stage 10. And that pieces need to be rotated and flipped, and that nine of them are needed to complete the puzzle. What changes later, as you can see in the solutions image above, is the complexity of the shapes themselves, not just how many blocks are needed to finish them off. It becomes tougher to envision just where things go as the shape itself is less standard.

The only real issues with Daedalian Opus come from its lack of features. Not saving any progress and relying on passwords means no leaderboards, which would have been nice for a game with a clock intimidatingly ticking away in it, but as far as the actual gameplay goes, it still gets the job done. It doesn’t invent some new kind of puzzle, and it isn’t some kind of riff on the falling block genre that was dominating the scene and causing all kinds of post-Tetris puzzle series to be created, but it handles its modest goal of “jigsaw-style puzzles with polyominoes” well.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.