It's new to me: Fatal Labyrinth

A game that was before its time in basically every way.

This column is “It’s new to me,” in which I’ll play a game I’ve never played before — of which there are still many despite my habits — and then write up my thoughts on the title, hopefully while doing existing fans justice. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

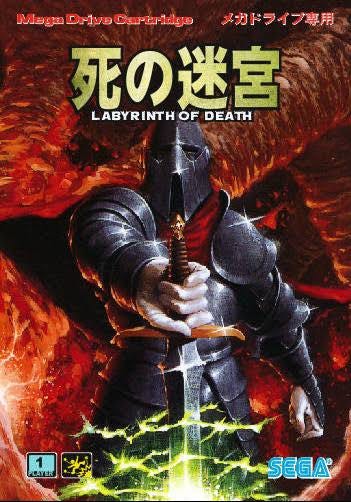

In 1991, when Fatal Labyrinth was given a makeover and a North American release on the Sega Genesis, the term “roguelike” didn’t exist yet. Roguelikes themselves, yes, but the term that would describe them as people understand them today had not been coined yet. This obviously means that “roguelike” wasn’t around yet in 1990, when Fatal Labyrinth came out in Japan on the Mega Drive.

In that inaugural release, it was known as Shi no Meikyuu, which translates to Labyrinth of Death. That would have been a wonderful name, too, but Fatal Labyrinth certainly does the trick of telling you just what this is about. In this first release, Shi no Meikyuu wasn’t contained in a physical cartridge, but was a downloadable game available through Sega’s Meganet system. Meganet was an early pay-for-play digital download subscription service that utilized dial-up internet to access. It never did make its way to North America, despite the fact that it’s where the market of people who owned (and would continue to buy the Genesis) actually existed, but it did end up being the predecessor to the Sega Channel, which, like Nintendo’s Japan-only Satellaview service, was ahead of its time but vital to the development of working online systems for home consoles.

Games on the Meganet service had to be small so that they could actually be downloaded and stored using the technology of the day. The modem used for Meganet had a max upload speed of 1.2 kbps: if you were there for it, remember how long it took photos and webpages to open with a 56k modem, and then try to imagine what downloading a game with a 1.2 kbps modem must have been like. My guess is that it’s the equivalent of waiting for an update to download on your Playstation 3, which is to say, you had time to both make and eat a sandwich while you waited.

Here’s some context for size comparisons between Meganet titles and what a Genesis cartridge was capable of. Phantasy Star II, which released in Japan in 1989 and North America in 1990, was contained within what at that point was the largest ever console cartridge, which allowed Phantasy Star II’s 768 KB of game to fit in there. Your smaller physical Genesis titles came in at 512 KB, though they’d certainly get larger: Alien Soldier comes in at 2,048 KB, Panorama Cotton is larger still, and something like Sonic 3 & Knuckles is over 4,000 KB thanks to its dual cartridge setup. Most Meganet titles came in under 128 KB, and it still took at least five minutes to download them at the speeds of the day.

Think of how the initial digital downloads for the Xbox 360, Playstation 3, and Wii were all smaller (and lower priced) games designed for their respective fledgling online services, rather than digital copies of physical games, and you’d be on the right track. Meganet games were full-fledged Mega Drive games, yes, not lesser by any means, but they had to be crafted with different limitations in mind. A roguelike with randomized elements that allowed for more expansive gameplay than the storage limit imposed on it was one such way to ensure that this was true: Fatal Labyrinth became replayable without you have to play it the exact same way, making it appear as if there was more here than its limited, sub-128KB size allowed for.

Fatal Labyrinth has the kind of setup roguelike purists can appreciate, as you start out in a town that lets you know what the title screen cinematic meant: a dragon is back in town, the castle full of evil it lives in has risen from the earth to let everyone know, and also the holy goblet that allows light into the world has been stolen by its forces. You then head into the castle to start exploring and climbing it, and don’t come back out until you’ve finished your quest of getting that Trees of the Valar-ass cup back where it belongs. There are no shops, no treasure chests, just items laying on the ground that might help you, or might be cursed, or might be inhabited by a ghost, or might be a mimic that’s waiting for someone to come by and make the mistake of thinking they won’t die when they pick up that bag of gold. Or it might just be garbage you don’t need, and you used up a turn to pick it up to find out, whoops, sorry about that.

Every action of yours (and sometimes inaction) is a turn, which, when taken, then allows all of the enemies on screen to then take their own turn. Walk a step? That’s a turn. Attack an enemy? You know that’s a turn. Pick up an item? That’s a turn. Attempt to turn in place to face a different direction without holding down the C button first to do it? That’s a turn. Pressing the action button when there’s no action to perform? That’s a turn, not for punishment purposes, but because it’s how you advance a turn while standing in place, which you might want to do sometimes. Don’t accidentally do this while surrounded by foes, or you might end up having a wizard put you to sleep right before a monster melts the armor off of your body while you sit there honk shoo-ing yourself to death.

Enemies will chase you, or sometimes, run from you, and in either case, you might end up attracting the attention of additional enemies by also running. You don’t want to end up surrounded: you want to try to isolate foes and take care of them that way, because if you have enemies on three sides of you, every time you attack one of them, all three will counterattack in succession. Your hit points won’t last very long if this happens, even if your armor manages to remain unmelted.

Luckily, hit points recover on their own over time, just from you walking around. The higher your level, the more hit points you regain at once, and there is also a ring you can wear that will speed that process up by recovering even more health at a time — more on rings in a bit. So you can play a little cat and mouse with some foes about to end you, running to regain some HP, before going in for the killing blow. Just be sure you’re not going to run right into an even worse situation for yourself when you do that.

And make sure that your character is well-fed enough for you to expend energy on such a chase, too. There’s a food mechanic in Fatal Labyrinth that sticks out, because it very much drives everything you do, and the order in which you do things in. You have to eat to survive within the labyrinth, but it’s not as simple as picking food up whenever you see some. While running out of food is (obviously) a negative — your character will slowly starve to death in the form of your HP ticking away — eating too much is its own problem. Your hunger is measured on a scale of 0 to 99, and if it goes over 80, you’ll start to take two turns to perform one action. It goes without saying that this is a serious issue, for movement and even more for battles. And if you fill up the gauge completely, well, you die. Just straight-up die. It doesn’t come off as if it’s judgmental a la Yume Penguin Monogatari, which is basically Fatshaming: The Video Game, but it kills you as quickly and as brutally as anything else in Fatal Labyrinth.

“Oh, well that’s easy to avoid then, I will simply not overeat.” How easy do you think it would be to count calories if you (1) had to for some reason and (2) they were never listed on the label of anything you eat? Because Fatal Labyrinth doesn’t tell you how much food is sitting there on the floor waiting for you to pick it up and eat it: it might be 10 units of food, it might be 20, it might be 50! All you know is that the food sprite indicates that there is food to be eaten, and what you need to consider is just how much you need to accept the risk of the fact that eating it very well might kill you, or, at least, overfeed you enough to make you take two turns for every step. Down at 30? Your odds are pretty good. Down at 10? You don’t have much of a choice, do you? Already at 50? Well… hopefully you find some more food soon, when your hunger is greater, and hopefully that one isn’t just a 10. Fatal Labyrinth doesn’t deal with all of the Seven Deadly Sins, but between the food mechanic, the mimics posing as bags of gold, and the kind of punishment that occurs in a roguelike the moment you feel as if you’re up to any challenge it can throw at you, it’s at least got gluttony, greed, and pride covered.

Then again, you don’t have to worry too much about ever feeling overpowered and overconfident in Fatal Labyrinth. Leveling up improves your hit points and hit point recovery, but your attack and defense are tied up in your equipment. The weapons will remind you of your own weakness again and again. The strongest weapons, like axes, have a low hit rate that’ll make you wonder if it’s worth the trade off of accuracy since you’re actually striking your foes so much less often. The weakest weapons, like spears and lances, are highly accurate but don’t have anywhere near the power of an axe, so you still feel like you’re attacking some foes forever to kill them. And swords are well-balanced, but this still leaves you with plenty of chances to miss or not strike nearly as hard as you might need. You get access to more powerful weapons as you climb the castle interior, but just know that you’re going to want a balanced collection for the times where an enemy (say, a ninja) seems too agile to be hit by an axe with any consistency.

You have ranged weapons, as well: there are bows, which aren’t particularly accurate but do let you attack from a distance, and you can also throw any weapons you don’t mind losing in the process. Shurikens are meant for throwing in the first place, but you can throw swords, lances, axes, whatever, too. They have a longer range than some ranged enemy attacks, as well, so if you plan things well, you can make room in your inventory and soften up a tough foe — or an immobile one — at the same time.

It’s also not just weapons you can throw: your old armor, shields, and helms, those can all be thrown, too. You don’t get a funny visual on-screen of what happens when you decide to just throw a helmet at a giant snake as it approaches you, no, but if you think real hard on it you’ll see it in your mind grapes. This is probably as good a place to mention as any that you do see your character’s new gear reflected on screen when it’s a different type: so, the switch from no helm to a leather one will change your sprite, and switching from there to a steel helm is an additional change, too. Pretty impressive for a game designed to fit the era’s dial-up speeds, and it sticks out even more so since nothing else about the game’s visuals tell you much besides that this game indeed released in 1991 without burning up a lot of storage space in the process.

You won’t know what a weapon is until you pick it up. Same goes for the various armor pieces. If you pick up what turns out to be a short sword and you’ve already equipped a short sword at some point in the past, you’ll be able to see its attack power without equipping it. Completely new items, though, must be equipped before you know how strong they are offensively or defensively, and you’ll want to check the item description even if it’s not new: it’s entirely possible that you’ve picked up a cursed item. If your item description says a weapon provides zero points of damage, then guess what? Cursed. You can solve this by dropping said weapon and picking it back up, but you won’t know you’re wielding something cursed and unhelpful unless you bother to look at what you’re putting on.

In addition to weapons and armor, you can also defend yourself with scrolls, rings, and potions. The three come in a variety of flavors, and like with weapons you don’t know what they do until you use them. Unlike weapons, what they do is not fixed: a short sword is always a short sword, regardless of what playthrough you’re on, but a scroll, ring, or portion, which are sorted by colors, won’t necessarily correspond to the colors they were on a previous run through the labyrinth. So maybe on one playthrough, a red ring helps you digest food more slowly so you don’t starve, and a blue potion heals a serious chunk of HP all at once, and an orange scroll heals whatever curse is upon you. On the next playthrough, red rings might actually curse you by darkening the entire level except for right around you, the blue potion might immediately send you to near-starving hunger levels, and the orange scroll might put you to sleep.

You won’t know what a given scroll, ring, or potion does in a given playthrough until you’ve tested it, which means you can’t escape their abilities (and punishments) forever without causing real problems for yourself down the line. You have to experiment with everything when you first get it, so that you don’t accidentally stockpile a bunch of items that are going to make it easier to kill you, and in place of the ones you actually could have used instead. So yeah, maybe it turns out yellow scrolls will put you to sleep, but try one out in an empty room and see once you first pick one up, so you can avoid holding onto those for the rest of the game. And you never know, maybe the red potion this time around will give you a one-point boost to your attack power every time you drink one: wouldn’t you want to know that early on so you can immediately down every one of them you find, which will both power you up and make room in your limited inventory for more potions?

That’s a lot of different kinds of items and inventory to manage, but thankfully the menu is split into easily navigable sections for each. Plus, looking at the menu doesn’t use up a turn or anything, so you can take whatever time you need to in order to figure out what you need to do to counter a curse, an enemy, whatever is in your way or holding you back. Only when you perform an actual action, or use an item, will time begin to advance anew.

Don’t worry, there’s more bullshit (complimentary) where the rest came from, though. Gold doesn’t actually do anything for you in-game since there aren’t any shops, but when you die, you’ll have a larger funeral with more of the town’s population in attendance. Is your vanity such that you can’t skip a bag of gold even knowing it might actually be a mimic? Is it worth it to you to go for it, anyway, because you want the experience points the mimic would give you? Venture forth at your own peril, regardless of your feelings in those situations.

Fatal Labyrinth is full of secret doors and passageways that you just have to poke around to discover. Can’t find a path anywhere? There’s a secret door to be found, so start looking in likely places and hitting the A button on those walls until something opens up. If you’re playing without a manual or without checking in on GameFAQs or what have you first, you’re going to be unaware of this. But if you’ve got roguelike instincts (or have just been playing an awful lot of Wolfenstein 3D of late), then you’ll have secret doors on the brain, anyway. Oh, you can also fall into hidden pits that drop you back onto the floor below, and all the monsters you slew will be back. Try not to forget about the pit when you return, either, because it becomes hidden again and you can keep falling down it.

The difficulty increases in a hurry. There are 31 floors, and 28 of them are randomized, while three of them are always the same in terms of placement. The rest are random in two ways: the order in which you play them in, meaning, the first floor on one playthrough isn’t the first floor on another, and in their actual item and monster placement. Maybe you’ll get lucky and have a couple of the floors where the exit is real close to the entrance late in the game, or maybe you’ll get those early and then know you’re in for a long, no-escape late-game. On the 10th floor (which is one of the three that are always the same), the weapons that aren’t actually weapons but are ghosts living inside of weapons that will attack you are introduced, as are the mimics living in gold bags. On the same floor is a wizard who will attack you with a spell that makes you “feel like dancing,” which is to say move around at random for a while, leaving you very wide open to being surrounded and attacked and killed.

Around halfway through the labyrinth, you’ll be introduced to the bugs that melt your armor: hope you’ve got another set of chain armor, because you’re not going to want to downgrade back to ring armor at this point. There are more, and more powerful, enemies from here on out, and by the time you reach the 20th floor, there is an apparent spike in the power of your foes, as well as how often the items you pick up are cursed. The last third is brutal, as the game expects you to have a full grasp of what every item is capable of, and also to have those items you need when you need them. You’ll earn your victory, if you manage to achieve it.

You do get a little bit of help that goes against the accepted structure of roguelikes, in that, after you die, you can continue. Not from where you died, lord no, but still. Every fifth floor is a checkpoint floor, and you’ll be sent back there after death if you so choose. That might seem real generous early on, but as the ways you can die in a hurry pile up, working your way back through floors 15-19 to get to 20, or 20-24 to get to 25, is going to feel as Herculean as just starting over.

Despite the fact that Fatal Labyrinth wasn’t a massive critical or commercial success, Sega has done an admirable job of making sure it stays available decades later. It was included in the Xbox 360 and Playstation 3 release, Sonic’s Ultimate Genesis Collection, in its North American form, and is currently available as part of Sega Genesis Classics for the Playstation 4, Xbox One (which also works on PS5 and Series S|X), and Nintendo Switch, as well as on Windows as a standalone title for $2.99. It wasn’t included in either of the Sega Genesis Mini consoles, but it’s not as if it’s unavailable otherwise, at least.

It saw a re-release in its own day, as well, as the Meganet version was included in a Japan-only Sega CD compilation of Meganet titles. This isn’t the definitive version of the game, however, since Labyrinth of Death did receive upgrades in the move from Meganet to Genesis proper, which is why Sega keeps trotting the one particular version out in the present. Still, it’d be something to get a modern Meganet collection, just to see what was only on that service, or what games like Fatal Labyrinth, Columns, and Flicky were like in their more distilled, download-friendly forms.

Fatal Labyrinth’s forced experimentation and exploratory nature, combined with its often brutal scenarios, mean it’s unlikely to appeal to everyone, but for those interested in roguelikes, its an early entry in the genre that predates the term, and, even though it allows a limited version of continuing after death, it still does its best to kill or at least make life real difficult for you as often as possible. An enjoyable use of an afternoon, so long as you don’t mind spending one to get your ass kicked and accidentally putting yourself to sleep once or twice.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

Definitely not a game for me with all the randomization and heavy punishment for what could come down to bad luck. It's interesting looking at the early history of downloadable games though.