It's new to me: Linkle Liver Story

Another Sega-exclusive action-adventure game from the developer behind Crusader of Centy.

This column is “It’s new to me,” in which I’ll play a game I’ve never played before — of which there are still many despite my habits — and then write up my thoughts on the title, hopefully while doing existing fans justice. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Sega might have had their answer for Mario in the form of Sonic, but as for the adventures of Link? They never quite figured out how to properly, “hey, we’ve got that, too” in the action-adventure scene. That’s not to say that the company’s consoles lacked quality offerings in the field that were published by Sega, because they certainly had them. Crusader of Centy, a Genesis title developed by Nextech, was one such game. As was the Sega Saturn’s Linkle Liver Story, which was also developed by Nextech and published by Sega, just like Centy. The difference there is mostly that Crusader of Centy received a North American release one year after its Japanese release, courtesy of Atlus, while North America had to wait until 2019 when a fan translation emerged to be able to play Linkle Liver Story.

It’s unclear why Sega didn’t publish the game overseas themselves, but you could ask the same question about Centy, too. The Saturn has a reputation for lacking games, but that’s not strictly true. It’s just that a not-insignificant percentage of the system’s library never left Japan. So even though Linkle Liver Story released in Japan in 1996, and Sega was still supporting the Saturn both home and abroad at this point, they left this one at home. Don’t blame the odd name, since those have certainly changed during localization before. But seriously, what does the game’s title mean? Is it supposed to be Linkle River Story, like maybe Linkle is the name of the river in the forest the game begins in? It was previewed in the Official Sega Saturn Magazine as “Wrinkle River Story,” so maybe that would have been it.

It’s not a quality issue, either: Linkle Liver Story isn’t the best action-adventure or action RPG game you’ve ever played, no, but it’s fun enough while it lasts — it’s pretty easy to see why it’s something of a cult classic among Saturn enthusiasts despite its flaws — and it’s an impressive example of the kind of 32-bit sprite work the Saturn was capable of. There are some nifty graphical flourishes in the game, like seeing the reflections of clouds moving in the gorgeous, clear waters of the forest, and the attention to detail paid to most, but not all, of the main character’s animations. It’s the kind of game that makes me wish the industry had spent a bit more time in the 32-bit space pushing 2D and sprites to new frontiers, instead of having so much switch over to polygons and 3D at the first opportunity. So it goes.

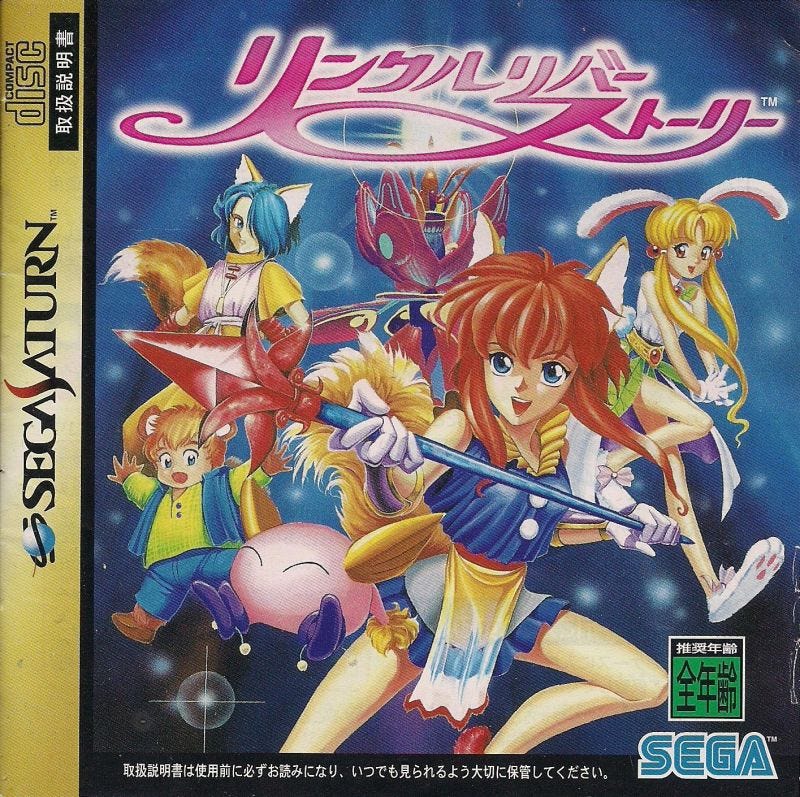

In Linkle Liver Story, you play as a foxgirl named Kitsch, who is training to become the new guardian of the forest she lives in. Said forest is attacked by an outsider, Hungaro the mole, who Kitsch’s master knows, this after she is warned by a cute little pink creature named Puchimuku about the attack by Hungaro on his own land. It turns out that no new plant or animal life is being born anywhere, because Hungaro stole the Mother Flower that creates the magical pearls that imbue said new life into the world, and is using those pearls for himself to create an army of servants and monsters. Kitsch and Puchimuku team up to solve the impending crisis of the world, one region and dungeon at a time, and Puchimuku is there for more than just the occasional bit of dialogue and cuteness. Kitsch can pick up her little pal and charge up a ranged attack wherein she throws him, and it’s useful against all kinds of enemies, and even some bosses.

Otherwise, your attacks come in two varieties: melee, or magic. You won’t be given the ability to perform magic for a few hours, which is no small thing in a game that is itself seven-to-eight hours long, but it’s still a useful skill once you do acquire it. The ability to perform magic is charged up by executing successful melee attacks, so you can’t lean on it so much as use it strategically in order to gain an advantage against a boss, or help to clear the screen of foes in a real pinch. There are four different spells to perform, one for each element, ranging from rapid-fire water bubbles to a defensive wind-based shield, and you are able to access them depending on what element your currently equipped weapon is attuned to.

The weapon system itself is unusually layered for a game of this length. As said, there are four elemental types for weapons — water, wind, earth, and fire — but within each element there are also a variety of weapon types, which you unlock after finding the “seed” for a particular element. It’s in quotes there, but the “seed” in question is literally a seed: you plant it in the appropriate area in the hub region, the Land of Seasons, and it allows you to start purchasing new weapons and eventually upgrade them, too. You do this via a Venn diagram-esque system, where attack speed, range, and power are all represented as points on a triangle. You walk to the combination of these aspects that you want — speed and power? range and power? just speed, or just power, and so on — and you’ll either get the weapon that corresponds to your position on the screen, or upgrade the weapon’s attack power if you already have it. To do either, you need pearls, which are collected from defeated foes: you’ll be doing a whole lot of weapon swinging, regardless of what you end up going with.

The game isn’t long enough for you to unlock every weapon that exists within it and upgrade them each the full four times, especially since you have four different elements with seven weapons each to focus on, not just one set of weapons. And that’s kind of the shame of things here: there is a ton of depth and customization to the weapon system, since you can decide that hey, you’re happy to sacrifice attack power in order to have a spear you can stab with quickly and from a distance in order to preserve your health, or maybe you want an all-power, no-speed option like the hammer. But you don’t really have the hours of game within to fully utilize it. You could, if you wanted to, play through with different weapon types, or maybe you want to round out your arsenal by equipping four different weapon types, one from each element, and focusing on just those. But honestly, the game’s low difficulty, in combat and exploration and puzzle-solving, is a poor match for the weapon system that’s attached to it all. It’s the kind of game you will enjoy enough on a single playthrough, but probably not one you’re going to go through again and again.

None of this is an indictment of the game so much as a realization that it could have been better than it was, if Nextech had leaned into this impressive weapon customization and upgrading system more in the actual game design, instead of just having it there, not being utilized like anyone playing could see it should be. A similar issue exists with some of the game’s stages and dungeons: the longer ones show off what this game could have been, as they’re a bit tougher to navigate and conquer due to the game’s limited save features (there are autosaves and checkpoints within levels, but you can only truly save on the world map) and the fact you’re at the mercy of random drops for health recovery once you’ve used your stored items. But too much of the game happens in a hurry, without asking much of either your skill or your curiosity. It all averages out to be a game that’s worth checking out if you’re a fan of the genre, but as said, you can’t help but see that there could have been a better version of this game out there, if only Nextech had spent more time focusing on making more of Linkle Liver Story resemble its best parts.

At least Linkle Liver Story does a good job of varying up your environments, and does so with a mix of various outdoor locations — forest, cliffside waterfalls, fields of wheat, caves — with some areas on the complete other end of that spectrum, like sci-fi or steampunk-flavored dungeons and towers, brought into the world by Hungaro and his anti-nature crusade. Not everything within is stunning, highly detailed 32-bit art, but at its worst the world is still interesting to look at because attention was paid to ensuring that this variety exists. The game’s puzzles, like its combat, are never overwhelming: if you see something you can hit to activate it, you should do so. If you see something you can break, you should do so, whether the game has told you to look for it or not. You might not know why you’re doing it, but you’re either going to get an acorn to heal with from it, or some pearls, or trigger a path of some kind to open up.

The bosses also aren’t difficult, but they at least often require you to figure out how you can even hurt them in the first place: surviving their attacks long enough to actually do something with that knowledge is the key here. Maybe they can only be reached with charged ranged attacks, maybe they need to have a shield taken down with a specific element’s weapon before you can damage them, maybe they’re only vulnerable to attack after attacking themselves, forcing you to dodge some splash damage but not get so far away from the attack that you miss your chance to counter. You’ll occasionally face off against a boss where you don’t need to think, just get up close and mash that attack button, but overall they’re enjoyable events.

Again, the most significant problem with Linkle Liver Story is that it feels like it could have been a better game: the ambition that went into the best dungeons and the weapon system could have been used in more places. A game being short isn’t an issue on its own, but this one needed a little more within to elevate it from merely a good time to a great one. Still, the game world is interesting enough, the characters and story enjoyable, and if you’re looking for something pretty breezy to work through in between more involved games, you could do a lot worse than Linkle Liver Story.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.