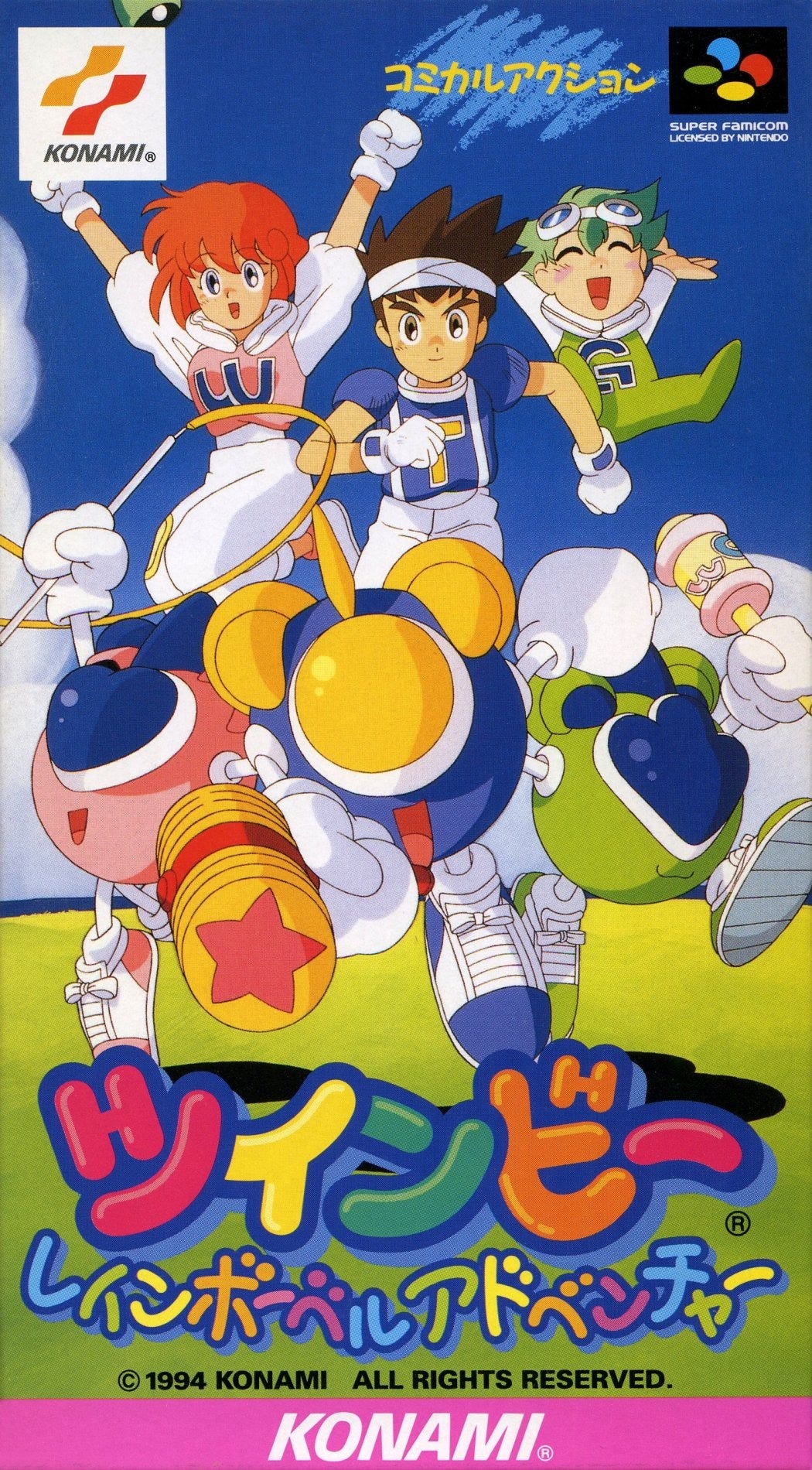

It's new to me: Pop'n TwinBee Rainbow Bell Adventures

Twinbee was a series of vertically scrolling shoot-em-ups, until Konami correctly decided it would also work as a side-scrolling platformer.

This column is “It’s new to me,” in which I’ll play a game I’ve never played before — of which there are still many despite my habits — and then write up my thoughts on the title, hopefully while doing existing fans justice. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Have you ever played a TwinBee game? You can certainly be forgiven if not, since Konami didn’t always support the series in North America, and much of its popularity in Japan comes not just from the games, but from its expansion into other media, like anime. Meanwhile, the North American (and European) versions of TwinBee games would often remove any dialogue or story bits, leaving you with just the gameplay. It’s a little tougher to do a recurring and fleshed out cast of characters if you reduce them all to just another ship in a shoot-em-up, is all, and that’s how Konami tended to treat the localized versions of TwinBee.

That is not to say that even these reduced-in-scope outings aren’t fun or anything like that, because they are: Konami, at its peak, was an incredible source of shmups, both vertical and horizontal, able to nail mechanics, feel, and sound seemingly with ease. They didn’t just make Gradius and thrive off of that, but even made a cute-em-up parody of it called Parodius that has its own success and following! TwinBee is certainly on the cute-em-up side of things, visually, but being cute doesn’t mean it’s easy or simplistic.

There are some layered systems in TwinBee games relating to how you can take damage, what your weapons are like, how to collect new ones, how to maximize scoring, and so on. There’s a lot to love about these shoot-em-ups, which made it all the more surprising to discover that TwinBee ventured into other genres. And not a new genre that would make immediate sense on the surface, either, like R-Type’s jump into the world of tactical games: TwinBee followed up the excellent Pop’n TwinBee on the SNES and Super Famicom with Rainbow Bell Adventures… a side-scrolling, 2D platformer.

Rainbow Bell Adventures never received a North American release, which is part of how I hadn’t played it until recently, but there is an English version floating around out there since it did end up the SNES in Europe. You don’t want to play that version, though: the English-patched Japanese original is the way to go, as there were significant changes made to the game’s structure for its European release, and as referenced before, the story bits were thrown out the window in its conversion from Japanese.

Whereas the Japanese version of Rainbow Bell Adventures is structured around the idea of being able to unlock new levels to play by choosing alternative level exits, and therefore being able to work your way around the world map how you would like to and with the ability to pause on any stage you’re stuck on and work on another in the meantime, the European version is more linear. You complete the levels in a specific order, so if you get stuck, you’re stuck. Oh, and you have to use a password system in order to save your progress, whereas Japan’s version has an autosaving battery backup. You’re going to have to download this to play it either way, so make the right call and go with the patched Japanese edition.

TwinBee might have been developed as a shmup half-a-dozen times before Rainbow Bell Adventures changed up the franchise’s genre, but Konami was no stranger to the side-scrolling platformer. In fact, you can sense a little bit of their Rocket Knight Adventures in Rainbow Bell Adventures, in the sense that you can fly around in eight directions at high speeds, and not necessarily while fully in control of where you’ll end up, either. Largely, though, Rainbow Bell Adventures isn’t like any one thing, outside of itself. It pulls clear influence and feel from a number of other platforming or action franchises, like Super Mario Bros. (you can jump on enemies’ heads to defeat them), Rocket Knight Adventures (the chaotic flying and charged beam weaponry), and even the original Sonic the Hedgehog (multiple pathway level design that works both horizontally and vertically, the speed to ensure you can get to your exit in a hurry if you want to play it that way, and a system where after taking damage you can briefly try to collect your lost upgrades again like you would rings in Sonic). You even start to get some Metroid vibes — well, in terms of progression, not in terms of Metroid’s actual vibes — as stages become more maze-like, more enclosed, and secrets need to be unlocked by way of experimental blasting and punching your way through walls instead of through flying into the stratosphere.

Combine all that with TwinBee’s own characters and style, the idea that hidden keys open up additional exits which unlock additional pathways in previously played levels, and a more customized path through the game world, and you’ve got yourself a platformer that isn’t much like anything else out there, even if it so clearly pulled from everything around it.

Let’s back up a second and talk about the game’s characters and their conversion from shmup to platformer. TwinBee games, by this point in time, featured three ships: the eponymous TwinBee, yes, but also GwinBee and WinBee. These ships already looked anthropomorphic in nature in their earlier designs — they have mouths! — so while Konami deciding Gradius’ Vic Viper should star in a platformer would have been an odd decision, the Bees all made inherent sense in this realm. They already had limbs, for instance, so it’s not like any changes to their design were necessary for them to be able to grip weapons or walk. The only change from any kind of established canon or convention (besides the genre shift itself, I mean) is that the bells you would collect for power-ups no longer come from non-enemy objects in the world, but instead, are secured by defeating enemies in the platformer.

The bells serve as upgrades and changes to your weaponry and your defensive systems. Collect the right bells, and TwinBee gets a hammer to bop enemies with, or if you’re WinBee, you get a longer-range whip attack, and GwinBee gets to throw rattles. You also can find shielding, invincibility, a pistol, and more, and you hold on to all of these (non-shielding and invincibility) upgrades until you take damage. At which point all of the corresponding bells in your possession fly out of your Bee’s body like Sonic’s rings, and you get a brief moment to try to collect them before they fall away into the ether. You have three hearts — three hits — in each stage, but collecting 100 miniature bells scattered throughout the level will grant you another heart. And stages have hundreds of the things.

You might think you need to collect all of them because they are there to be collected, but if you’re trying to scour every inch of a stage in order to find all of its secrets, you’re going to want to ration your collection of these bells at least a little bit. That’s because you have three hearts, but only one life. There is no continuing from where you left off within a stage. You can continue from where you were in the game’s overall progress, but you have to start the level you died in back at the beginning of it.

Actually, all of that plays into part of what makes Rainbow Bell Adventures stand out so much. You can spend 10-12 minutes in any given stage, as they are massive, attempting to find any hidden secrets or pathways it might contain. You can also complete them in a matter of seconds, if you just speedrun right to the nearest exit. It’s actually a little confounding at first, when you think you made your way through a stage early on at a brisk pace of 90 seconds or two minutes, and the game tells you that the goal time for that level was more like 12 seconds. It all makes more sense when you realize it has all been designed as both an exploratory, slow-going experience, and as one where your lone goal can be trying to navigate and complete it as quickly as humanly possible.

The weaponry isn’t the only difference between the three playable characters. TwinBee is kind of the most balanced option, with what end up seeming like standard charge times for both the projectile punch beam and the rocket-assisted “jump” that sends you flying in whatever direction you pointed for a considerable amount of time and distance, whereas GwinBee and WinBee each have longer charge times for one or the other, so they tend more toward the extreme of either combat readiness or “I wonder if I can quickly and successively launch myself across much of this stage” play. Your choice in character is part personal preference, and part what it is you are expecting to get out of the level you have chosen to play upon returning there, but you can do anything with any of the three. It just might be done a little differently, depending on the charge times in play.

You might tend to think of games the SNES never received from Japan as almost exclusively JRPGs, given the amount of localization work needed to get them into a playable state for non-Japanese speakers, but no. The Super Famicom is also loaded with platformers and plenty of other games from other non-RPG genres that never made it this far west, for one reason or another. Rainbow Bell Adventures might have been an oddity as a side-scrolling platformer based on a series of shoot-em-ups, but it’s one whose quality is high enough that it should have received the same kind of international support as other Konami projects, like Rocket Knight Adventures. At least it’s playable now in its superior Japanese form, and in English, too, thanks to fan translaters. And you should play it, if you’re into platformers at all, or want to see what other kinds of genres the TwinBee crew easily slot into.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.