It's new to me: Rad Racer

Before there was Final Fantasy, there was Square taking their turn at an OutRun-style driving game.

This column is “It’s new to me,” in which I’ll play a game I’ve never played before — of which there are still many despite my habits — and then write up my thoughts on the title, hopefully while doing existing fans justice. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Different things come to mind for different people when Square Enix is mentioned. Final Fantasy! Dragon Quest! Tomb Raider! Ugly mobile ports of classic games that deserve better! What doesn’t come up nearly as often as the above is that they’ve got a few racing games under their belt. Way before the merger with Enix, before Final Fantasy, even, there was Rad Racer. Released as Highway Star in Japan, it was, from Square’s point of view, a way to show off the 3D programming skills of Nasir Gabelli. From where Nintendo of America and Nintendo of Europe were sitting, Rad Racer was a way for the company to respond to kids and parents wondering why OutRun wasn’t on the popular NES with, “we have OutRun at home.”

Rad Racer is a better game than summoning that meme implies, but it is no OutRun. Barely anything is, of course: even Sega’s own ports and conversions of the arcade classic and its sequels didn’t quite capture its essence for some time. Rad Racer is plenty fun in its own right, albeit more frustrating to play than OutRun. It does have one thing going for it, though, in that it’s wildly fast: it might be lacking visually compared to OutRun’s 16-bit Super Scaler arcade experience, but you fly — often to your own detriment — in Rad Racer, and that’s the appeal. That feeling of unease when you’ve hit top speed and a turn is coming up quick, that moment when you can either panic or stay focused when the road ahead of you is suddenly full of cars blocking your path… that’s when Rad Racer is at its best.

I don’t think Nintendo’s publishing of Rad Racer outside of Japan was a direct response to OutRun, in the sense that anyone at Nintendo was concerned that Sega had a ton of momentum and popularity in arcades and it would eventually translate to popularity in the home market, so much as it was a chance for them to capitalize on that popularity of the arcade racer with their own (published) go at something similar. Which makes a ton of sense: Rad Racer couldn’t replicate OutRun’s feeling of sitting in a car and driving, like the arcade cabinet tried, but it could do its best to make for a surprisingly fast-paced experience you’d need to play and play and play again to thrive at. And since you needed a Sega Master System to play OutRun at home in 1987, and that wasn’t really a thing in American homes, there was a clear gap in the market and opportunity to wedge something in there.

Coincidentally, the North American editions of Rad Racer and the SMS conversion of OutRun actually released in the same month: October of ‘87. So, even if Nintendo publishing Rad Racer in North America wasn’t actually an attempt at stifling Sega’s own console properties on a system where Nintendo had already contractually ensured existing and popular third-party games wouldn’t release, actually trying to do that probably wouldn’t have looked much different. No wonder Sega was so intent on toppling Mario, specifically.

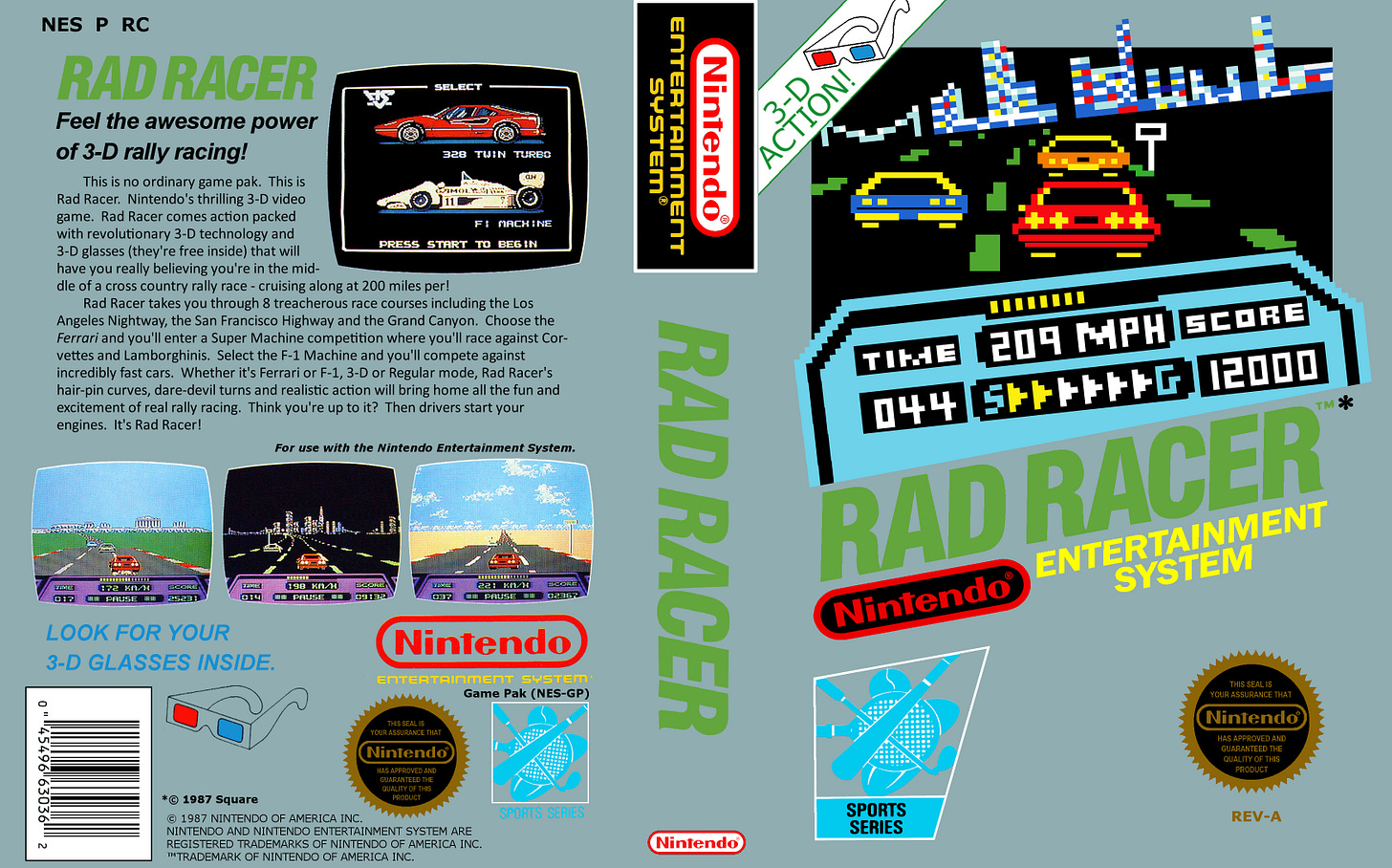

Like so many games from this era, everything you need to know about Rad Racer is contained within the manual, as the game gives you no indication of how anything works or what you can do. There’s no tutorial, no screen explaining how the controls work: you just turn the game on, select either a 328 Twin Turbo Ferrari or an “F1 Machine,” and then you’re shown the first course right before beginning to race — the 328 is a Ferrari, by the way, in case you thought I was 100 percent joking about the “we have OutRun at home” thing. Which vehicle you use doesn’t matter, other than visually speaking: the other cars are replaced on the highway to correspond with your choice, so it’s either other F1 vehicles if you go that direction, or assorted other street cars getting in your way if you go with the 328.

Visually, it’s no OutRun (arcade), but it stacks up well enough against OutRun (Master System). There’s a true sense of speed, which isn’t the case even in some Genesis ports of arcade racers. Rad Racer was built from the ground up for the NES, and its backgrounds can come off a bit sparse at times, but this was a worthwhile sacrifice to get the car moving as fast as it does. The backgrounds are at least varied: the first track starts out on a coastline, as the name Sunset Coastline implies, and you start to work your way toward a city, with the sky darkening as you go to show the passage of time. The second track is on a mostly unlit highway at night, with a fully lit-up city in the far background — that’s where you’re headed next, if you can survive this desert no one bothered to illuminate. It’s got a different visual vibe than OutRun, to its credit — the only reason that game keeps getting brought up here is because it’s difficult to disconnect the two, even if Rad Racer does do its own things as well.

The controls are easy enough, if you know them: the A button accelerates, B brakes, pressing/holding Up on the D-pad turns on an infinite turbo, and pressing down changes the music. The last one of those defaults to not being on, leaving you with the sound of your car’s engine as you speed up and slow down and hit the turbo, but there are a few tracks to choose from, like you’re switching stations on the radio. The music is fine — the first one is the standout, easy, and the second of three has some life to it as well, but it’s nowhere near as memorable as basically anything else composed by Nobuo Uematsu. Hey, I said Rad Racer predated Final Fantasy: he was actively composing before that was made, you know.

[A note: this song isn’t actually called “Sunset Coastline; that’s the name of the game’s first race track. The music in Rad Racer is just named things like “BGM 1,” and the song in the above video is, in fact, BGM 1.]

As for that turbo, it is unlimited in its use, but it has a ceiling. It doesn’t actually make you drive faster, in terms of your car’s top speed, so much as it allows you to reach that top speed sooner. This isn’t like nitrous in Ridge Racer or Cruis’n Blast or what have you: turbo is just meant to help you max out faster, and in the process save you precious seconds in between checkpoints that extend your remaining time on a track. You’ll know you’ve reached a bit of Rad Racer zen when you can carefully balance letting your finger off of the A button to slow down and ramping up turbo to get back up to top speed in between taking turns and dodging the other vehicles on the road. If you don’t find that balance, you’re going to run out of time even if you don’t crash. And you will probably crash: the roads are full of obstacles, from trees to turn signs to billboards, and if you hit them, your car will go flying through the air.

This is actually one of the more frustrating elements of Rad Racer, and it’s because it has the problem Excitebike does, which is that it takes for-ever for you to be able to start driving again after a crash. In Excitebike, at least, the punishment for this extended waiting period is just that you might not finish with the top time. In Rad Racer, though, you’re racing against the clock, and when the clock runs out, you lose and have to start over. Rad Racer’s courses are also quite bit longer than those in Excitebike, so restarting the former is a little more of an ask than the latter, especially when you feel — correctly or not — that The Game is at fault for your loss. It’s on you, of course, since you crashed, but if everything went a little quicker, maybe you would have kept going. That’s how you’ll react, because you’ll have plenty of time for your train of thought to reach that station before the car starts moving again.

Crashing at high speeds in Rad Racer can be frustrating, yes, but it’s also extremely funny, so who’s to say if it’s good or bad. The annoyance at hitting a sign on a turn that came out of nowhere — well, out of nowhere for 255 kilometers per hour, anyway — is replaced by joy at seeing your car spiraling through the air, continuing to score points while out of your control. Points are gained based on distance traveled, and you might not be driving as you catapult over the roofs of other cars and down the road, but it’s still distance gained. It takes too long to get back to driving under your own power after a crash, yes, but seeing a Ferrari launch itself over the cars in front of it and some additional obstacles, scoring points and getting right back to the middle of the road in the process, is still funny.

Bumping into the back of another car can actually be a blessing sometimes, as it slows you down dramatically, but far less than if you, say, veered off the road and into an obstacle on the side of it on a bungled turn. In every instance, whether it’s bumping into a car in front of you, letting off the gas or turbo, or even hitting the brakes, you’d much rather be temporarily slowed down than to crash: again, crashing takes so long to recover from, but if you’re still above 90 km/h, you can engage turbo at any time and reclaim your lost speed in a hurry. And if you were at or near max and temporarily slow down, you’re probably only falling to 150 or so at minimum, anyway, so you won’t have all that much room left to climb. Crash, though, and obviously, you’re back down to zero km/h, in addition to the whole waiting to get going again thing.

One thing I love about Rad Racer’s design is that running out of time isn’t automatically the end. When you’re out of time, you can no longer accelerate, and your car will begin to slow down. You can still control your vehicle, turning left or right, and if you manage to cross a checkpoint after running out of time as your car decelerates, you’ll still receive a time extension as if you had come across it with time left to go. It allows for a build-up of anticipation and the hope that you’ll live to try to make it to one more checkpoint: while you won’t always succeed in keeping your race alive, that tension and the occasional payoff for it is both wonderful and welcome. How far you made it and your position relative to the next checkpoint will show up on the map if you fail, only adding to the “oh I was so close!” feeling; that’s one way to convince you to give it another try. It’s a very arcade-centric feature in a game that released on consoles, really, but speaks to how Rad Racer worked on keeping you invested in trying again even after you had a brutal go of things with crashes and its difficulty.

A thing I do not love about Rad Racer’s design is the 3D element. It’s optional, thankfully, and turned on and off by pressing the Select button during a race. For the Famicom release, Highway Star, a console peripheral — the Famicom 3D System — was utilized, so the 3D worked better there. The Famicom 3D System utilized active shutter glasses to create a 3D effect. While the peripheral was a failure and not exactly the most pleasant thing to use in the world, it at least worked on the games that utilized it, Highway Star among them. Rad Racer, though, just had some pack-in 3D glasses like you’d get at the movie theater, so the quality was lower, and you have to consider that these televisions weren’t necessarily built with 3D in mind, either, so getting the settings just right was a whole other thing to deal with. I understand why Square worked on implementing 3D in Rad Racer, and 3D certainly can make this type of game even better, but it didn’t need the gimmick. It could have stood on its own merits.

That being said, how Square didn’t bother to rework Rad Racer on the Nintendo 3DS, like Sega did with OutRun, Afterburner II, Super Hang-on, and a whole bunch of other titles that utilized 3D and pseudo-3D technology in the 80s is beyond me. The absurdly dark overlay that the 3D graphics created could have been dealt with with this improved tech, making for a better-looking and better-working 3D experience. Square remasters and re-releases so much — was putting a popular NES game that, for all the criticism directed at it was still well-regarded in its time, on a system that could actually make it feel complete for the first time that much of an ask? Plus, Square could have included the additional track that was used for the 1990 Nintendo World Championship in such a re-release.

There was a limited-edition cartridge release of the 1990 Nintendo World Championship games, which included modded, timed versions of Tetris, Super Mario Bros. and Rad Racer. In 2019, Seattle’s Pink Gorilla Games (a shop run in part by Kelsey Lewin of Video Game History Foundation) happened upon one of those cartridges at the bottom of a Safeway bag full of pretty typical NES fare, and ended up cutting the surprised seller a check for $13,000 to part with it. How much it was then sold for to a collector remained a secret at the buyer’s request, but Pink Gorilla Games themselves released an authenticity verification video which also asked if it was worth $20,000, so you get the idea of what one of these could go for.

Which is all a bunch of color to get to me just asking, “why not?” again of Square. Now the 3DS is out of commission, its shop shutting down (or shut down, depending on when you read this), and no Rad Racer with bonus 1990 Nintendo World Championship and working 3D exists. It’s always something with those guys.

As for the Rad Racer we did get, though, it’s a quality game, with speed surprising for an NES title. It’ll take you some time and a whole lot of practice to finish the game’s eight courses, which feature progressively faster and more aggressive drivers to share the road with as it goes, but the only way you’ll be able to play is either with an original copy or emulation: Square hasn’t bothered releasing it outside of its original Famicom and Famicom-adjacent family of home and arcade systems.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.