It's new to me: Snatcher

Before Hideo Kojima made Metal Gear Solid and... well, lots more Metal Gear Solid, he was behind a 1980s cyberpunk graphic-adventure, released on platforms you probably didn't have.

This column is “It’s new to me,” in which I’ll play a game I’ve never played before — of which there are still many despite my habits — and then write up my thoughts on the title, hopefully while doing existing fans justice. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Much was made about Hideo Kojima leaving Konami and Metal Gear Solid behind back in late-2015, in no small part because it meant he was going to be free to make games that, well, weren’t Metal Gear Solid. Death Stranding was the first such independent, non-MGS release for Kojima and his studio, Kojima Productions, but it’s far from the first non-Metal Gear game that Kojima directed. There are the Zone of the Enders games, of course, but well before that, in between the initial MSX2 releases of Metal Gear and Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake, Kojima and Konami released Snatcher, a graphic-adventure cyberpunk mystery.

Snatcher has had multiple releases in Japan across multiple platforms, but in North America, it just got the one, six years after its initial debut. Like with the pair of early Metal Gear games, Snatcher came out on the MSX2 computer system, and the NEC PC-8801, during 1988’s holiday season. It got its first console release in 1992, for the PC-Engine Super CD-Rom, but it did not get a localization for North America’s equivalent to that system, the Turbografx-CD. Instead, the west would have to wait until 1994 for that, when Konami decided to port Snatcher to the Sega CD add-on for the Sega Genesis. Six years after its initial release, released late into the lifespan of the Sega CD, which sold just 2.24 million units in its day… an English localization of this graphic-adventure was a rare, rare thing, as its sales numbered in the thousands. It’s hard enough to find a working Sega CD in 2021, never mind an authentic copy of one of its commercial failures, and it doesn’t help that neither the Playstation nor Sega Saturn ports that followed made it out of Japan, either.

With all of that being said, times have changed, and it’s much easier to play Snatcher than it used to be. You don’t need a Sega CD to play games from that system, thanks to emulation on a computer, or if you’re into the modding scene at all and have maybe hypothetically tweaked your Sega Genesis Mini until it can play games that are definitely backup copies from that system’s add-on devices, that would suffice, too. It’s also easier to know Snatcher exists than it used to be: Kojima is much more of a household name than he was back in 1994, years before the initial entry in the Metal Gear Solid franchise had even released, so you have more cause to go and see what games he directed or produced than you would have nearly two decades prior. It’s only recently that I finally finished all of the Metal Gear games — a story for another day — so my own realization that Snatcher is a thing that exists that I should find a way to play came only a little more recently than that.

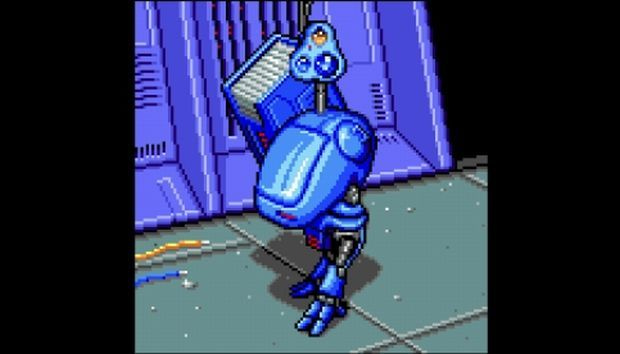

While Snatcher isn’t a Metal Gear game, it is set in that universe. A future version of it in the mid-21st century, well after the days of Snakes and Bosses, but in that same universe nonetheless. We know that because your little robot detective pal is named “Metal Gear,” and his creator goes out of his way to tell your character, Gillian Seed, that he was designed and named after the Metal Gears from back in the day. Just, you know, tiny, and with judgmental wit in place of nuclear weapons. A club you’ll spend some time in during your investigation is named “Outer Heaven,” and of course, the first time the words “Metal Gear” are uttered, the response is, “Metal Gear?!” as it should be. Snake would be proud.

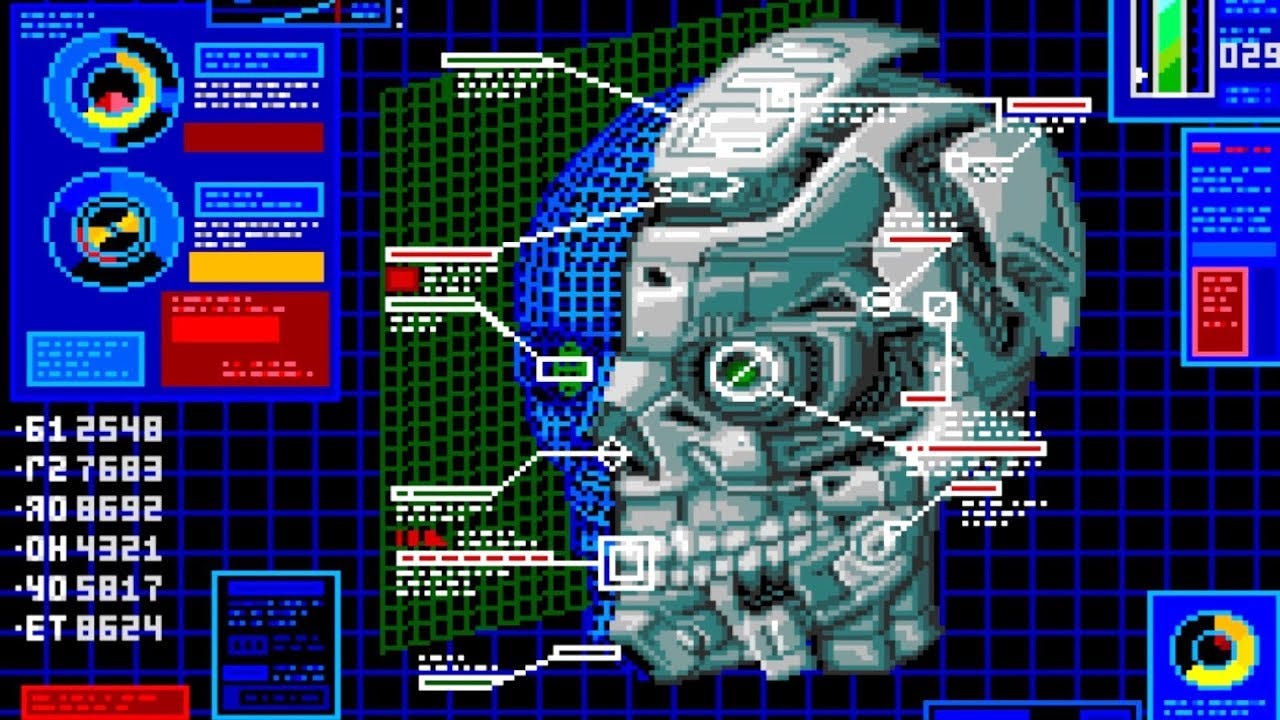

You will be shocked, shocked I say, to find that Kojima filled Snatcher with references and odes to films*, be they very obvious ones like the Snatchers themselves, which out of their human-skin-disguises look a whole lot like T-1000 Terminators, or that nearly everything in the game owes a debt to Blade Runner. It is a cyberpunk game with a detective looking to see who is actually human and who is just pretending, after all.

*If you want to know all about Kojima and his influences from film and otherwise, the podcast Pod Sans Frontieres, which does an extremely deep dive on everything in the Metal Gear games and what it all means and where it originated, would be a good time for you.

Snatcher might be “just” a graphic-adventure game, but it utilized the extra features of the Super CD-Rom and Sega CD add-ons by implementing what was, at the time, a ton of voice acting, as well as quality audio for its soundtrack. The voice acting wasn’t included in the original releases back in ‘88, since there wasn’t enough space for that sort of thing at that time. The North American voice acting from 1994 was actually a point of contention for critics, as some felt the actors did a believable, enjoyable job, while others felt, well, the opposite. I actually enjoy the voice acting: it’s light years ahead of what Resident Evil would end up doing later on in the 90s, and any weird vibes it gives off at times fit in well with the game world. That’s not just a way to dismiss criticism, so much as to point out that it’s vital for it to make sense within the context of the world it’s in, to add value to the whole idea of what you’re playing, and Snatcher’s voice acting accomplishes that. It does a great job of adding nuance to the dialogue, characterization to the characters, and building out this weird, futuristic world on the brink of destruction, just like the soundtrack so successfully does.

You play as Gillian Seed, who, along with his wife, Jamie, has lost his memories but is aware that his background had something to do with the Snatchers. Who, true to their name, are snatching up humans and then replacing them in society with lookalikes. So, Gillian becomes a Junker, which is basically a detective but specifically for finding Snatchers, in order to find out more about his and his wife’s past. The two are separated, by the way: while they know they were married back when they had their memories intact, they are practically strangers now, and the expectations of being together when they don’t remember each other was just too much.

Like with Blade Runner and replicants, anyone could be a Snatcher, so much of the game has you on edge, wondering if the person you are talking to at that moment is a Snatcher, will end up being snatched, or is just a regular kind of weird and off-putting. It’s an impressive feat for a game that is, primarily, a text adventure, with you trying to piece together how to unveil the next clue or story beat through a combination of Investigating and Looking. If you’re familiar with visual novel style games or graphic mysteries by now, Snatcher will look very familiar, but if you haven’t spent time going through, say, Famicom Detective Club outings since their recent release, or haven’t logged years and years in the Ace Attorney mines, you might find some parts of Snatcher’s setup annoying. Granted, that’s because some of the gameplay mechanics are very 1988 graphic-adventure, so there is a lot of guessing and redoing things in order to get them in the exact right order to open up new dialogue options or destinations, but you’ll eventually get a handle on the game’s internal logic.

And if not, well, spoiler-free guides exist, and Snatcher’s world is one worth visiting even if you’re just going to follow along with a guide the whole time.

Gillian is a good detective, but he’s also absolutely a perv dipshit, as you’ll discover whether you meant to or not through the trial-and-error investigative system. If Gillian is talking to a woman, he is trying to figure out how to get a phone number or a date. It’s offputting, but luckily, the game agrees: your little metal friend is always giving you hell for that behavior, and Gillian is made to look like a doofus in some way or another whenever he’s chasing the wrong kind of lead on the job. If you persist in making advances, then the game switches from trying to make Gillian feel bad to making you, the player, feel bad: you can get a fake number after pestering a dancer long enough, punishing you for trying to wear her down, and Mika, who works at Junker headquarters with Gillian, will make it clear you’ve crossed a line into harassment and infidelity if you keep it up.

That helps a lot, really, since it punishes players for indulging Gillian’s worst impulses, and since the North American version is a bit more cleaned up in some ways than the Japanese one is — the 18-year-old model in North America’s release sure was not 18 in the original versions, for instance — the chastising doesn’t feel out of place, either. It’s a little harder to blame the game for also being kind of pervy, since now it’s more like “well you’re the one reading into it that way.” Shouldn’t you be trying to make things work with Jamie, Gillian? God.

While the game features Kojima’s traditional fourth-wall-breaking, tension-relieving moments of humor, it’s never as fully out of place as his games can sometimes make it. No one wets themselves or suffers from comedic diarrhea, or at least, I didn’t see anything like that: there was no big cutscene interrupting a mission because a Snatcher really had to find a toilet, you know? The story is mostly pretty serious, focusing on the kind of big picture stuff that certainly helped inform what would be coming out of the Metal Gear series next upon its switch to 3D and the Solid era. It’s a very human story, for all of its sci-fi elements, which is, traditionally, what makes for some of the best sci-fi going. It’s supposed to be a distorted reflection of our own time, our own fears, and so on, with sci-fi being a way to set it outside of our direct experience. Snatcher succeeds at that very thing with its story, themes, and setting.

It’s also hilarious to find out that Kojima was already so… Kojima at this point in his career. Snatcher initially released in 1988, but it already featured a 30-minute segment of exposition right at the climax, where the big bad details the how and why of the plans for the Snatchers and the world, filling in a whole bunch of blanks that had not yet been filled in by the story regarding essentially everyone involved. Kojima and Konami weren’t at the Guns of the Patriots level where you should be sure you’re completing Snatcher while it’s still early enough out that you have time for it to get late, but still, this is like an eight-hour game where the last 30 minutes or so before the credits are mostly one person unveiling all that had yet to be unveiled. None of this is a criticism, either: it works, both in-game and as a storytelling device.

The only parts of Snatcher that don’t quite land are the shooting segments. They’re easy enough through most of the game, but the end-game ones are more challenging, since they’re relentless, with little room to miss your shots. They’re probably a whole lot easier if you have a light gun to use, since Konami made Snatcher work with the one from another of their games, Lethal Enforcers, but let’s be real. If you’re playing Snatcher now — a game that just thousands of copies of ever existed in English — you’re probably doing it on a setup where you can save your state whenever you want to, so you can get through those segments without whatever annoyances might have existed back in ‘94 easily enough.

It’s great and all to get a glimpse at what was going on in Kojima’s brain before the days of Metal Gear Solid — the love for films and philosophy were already there, as well as what we can see by this time is also a clear love of redheads — but Snatcher, on its own merits, is worth playing. It’s just a damn good cyberpunk world and mystery, with a future version of Japan worth exploring and a foe worth both figuring out and defeating. The voice acting can be a little off at times, sure, but it’s mostly endearing, and helps build out the world and characters, and the soundtrack is as vital to the experience as the animation and art style. Like with the best graphic adventures and visual novels out there, I’ll be revisiting Snatcher somewhere down the line, once I forget the finer points of its plot. If you want to find an excuse to replay a mystery you already know the solution to, well, that’s a game that is built on a much stronger foundation than just that solution, isn’t it?

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.