It's new to me: Tenshi no Uta: Shiroki Tsubasa no Inori

A JRPG developed by the iteration of Wolf Team that would go on to become two studios you probably know better.

This column is “It’s new to me,” in which I’ll play a game I’ve never played before — of which there are still many despite my habits — and then write up my thoughts on the title, hopefully while doing existing fans justice. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Tenshi no Uta was a JRPG series in the early 90s, and not one of the three entries made it out of Japan. It’s not totally unknown elsewhere in the world, but it is obscure enough that the three games share a single Wikipedia page, and you don’t need to scroll down to read all of it on a desktop. Tenshi no Uta: Shiroka Tsubasa no Inori — which translates in English to Song of the Angel: Prayer of the White Wings — is the third game in the series, the lone Super Famicom release, and also the only one of the three to receive an unofficial translation into English.

It’s not a sequel, not really, but also not really a remake of those games, either. It takes place in a different world than the original PC Engine Super CD-ROM² games, but uses some of the same narrative beats and plenty of the same general tropes as those titles: it was meant to be something of a Tenshi no Uta catch-all for players who hadn’t experienced what the series was before, on the more popular of the two platforms.

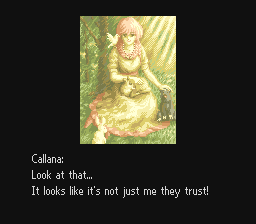

Being on the Super Famicom instead of the PC Engine CD did come with some drawbacks and cuts: being the newest of the three doesn’t matter so much when you’re going from CD storage and all that entailed to a cartridge system unable to do some of the same things. For instance, the voice acting is gone, but at least the developer, Wolf Team, tried to make up for these differences where they could by including large-scale character art in cutscenes that used text instead of voices. It’s more than some other developers used to the additional storage and power of systems like the PC Engine CD managed when they shifted their work over to the Super Famicom: Ys V, for instance, felt like a massive downgrade on the presentation side because Falcom didn’t try to directly compensate for the loss of some of the features that players of their titles on other platforms were used to.

Shiroka Tsubasa no Inori isn’t a bad-looking game, but the cutscenes and larger character portraits are the highlight, and it isn’t close. It’s just kind of bland and generic-looking elsewhere; there are some real nifty, large-scale creature designs and sprites that stick out a bit since the game — and series — are focused heavily on religions and demons and literal Hell, but the overworld map looks like a bunch of other SNES/SFC JRPGs, and the actual sprites for your characters are fairly nondescript, with none of the kind of heavy lifting put in to translate what you see on the box and in cutscenes to the sprites as you would get in, say, Final Fantasy VI, which released the same year. It looks like they tried to make character sprites that remind you of the tall, lean, detailed ones of the Phantasy Star series, but then kind of forgot to sort out any of that, so you instead end up with leaner sprites that aren’t quite tall enough to squeeze in the detail Sega was able to in their own RPG series. Again, not bad, but it just kind of is, and its look is most memorable for its lack of distinction.

Where Shiroka Tsubasa no Inori does manage to be memorable comes outside of how it looks. It’s one of the early joint efforts between composers Motoi Sakuraba and Shinji Tamura, who have partnered together 30 times over the years, most recently in 2020. There are some hints as to where Sakuraba’s sound would go within Song of the Angel, but it’s far less distinctly him than you might imagine, considering how generally easy it has been, historically, to know when you’re listening to a Sakuraba-composed game.

Shiroka Tsubasa no Inori leans heavily on romance in its narrative, basically from the outset through its end. The game begins with your protagonist, Rayard, meeting Callana out in the woods in the middle of an errand that he’s running for his father. She’s beautiful, surrounded by woodland creatures, and wants to speak with Rayard since the animals don’t seem spooked by his presence. The two hit it off, with Rayard later finding out she’s part of a traveling circus troupe and a singer with a voice as enchanting as the person it’s coming from, and… well, think about the name of the game for a bit and the information you just read, and you can probably figure out both that the two fall in love, and also who or what Callana might actually be.

Callana and the circus troupe end up departing for another town, and Rayard makes the mistake of not saying goodbye because he’s too upset about the parting occurring at all. Callana would have stayed for him, and it’s only after Rayard’s friends let him know he’s being a dingus that he decides to set out to find her and apologize and to give love a chance. That’s when the party finds out that Callana’s been imprisoned by a powerful noble who is basically going, “hey, agree to marry me against your will and I won’t hunt down everyone you know and imprison them until your spirit is broken.” Reynard and his pals end up meeting up with a nascent rebel army that thinks this guy is a jerk for reasons other than kidnapping a songstress, and work together to free Callana: they’re now all on the run, forming new relationships and working with each other to help themselves and those they meet while they’re putting distance between a very angry noble who was enough of a problem even before he received extra powers from a demon to better exact his revenge against those that have wronged him. Pacts with a demon, what could go wrong?

Shiroka Tsubasa no Inori might navigate through some other territory, like with the rebellion and its focus on demons (and their less evil counterparts), but the central thrust of it all comes from the romance. The game begins there, it continues on because of it, with every future event occurring because Rayard and Callana are just trying to make this thing they want so badly to work.

The narrative is the highlight of the game, which is some good news/bad news. It’s enjoyable to see this kind of story and central focus, but it’s still told in a game that doesn’t quite land the rest of the package as much as it needs to in order to move the whole title from intriguing to must-play. Battles, for example, have a mechanic that sounds great on the surface, but isn’t quite as baked as it should be in practice. Rather than fighting the monsters and demons you find in your random battles throughout your journey, you can try negotiating your way out of conflict instead. Even just trying is a positive, as you’ll get a different form of experience that helps you better form friendships with the creatures you meet along the way even if the enemy in question essentially responds with [Jason Lee voice] “I’m a fucking demon.”

Bosses scale to your level, so you don’t actually need to grind for standard XP by defeating standard foes, which means you’re free to attempt to talk your way out of it again and again, fighting when you have to and maybe getting some bonus rewards for not slaying beasts whenever they agree it’s in their best interest to let you pass. It’s an intriguing mechanic, but as said, one that still ends up feeling a little half-baked here, especially since it’s not really explained to you the way it probably needed to be in order for you to get the most out of it. Consider that early on, you’re going to be forced to fight basically every monster until you’ve advanced your ability to speak to these enemies, picked up their languages around the world, etc., so… you could get pretty used to fighting and forget all about improving your nonviolent tendencies. There’s no real penalty for fighting, like there is in something like Undertale, and because of the way things are designed, you’re going to have to fight plenty even if you would prefer to: there’s no pacifist route. Should there be? Maybe not, but I do still think it would help if all of these unusual systems were explained a little better in-game.

I will say that it’s possible that the game’s manual does go in-depth on it all so you know the score from the outset, but that was not part of the unofficial translation done by Translation Corpotation. Which is not a dig at their work by any means: translated manuals are a rarity, and Song of the Angel itself is wonderfully translated, with additional work performed to improve the actual quality of the game itself, not just to give you the original form of it in English this time. In their translation, there is proportional font in both the menus and in dialogue, which helped to modernize the look and layout of them a bit, and it’s also clear that a ton of work went into making sure this was more localization than direct translation, too.

There’s nothing significantly wrong with Song of the Angel, but it also feels like it’s missing something that easily compels you to keep on with it. The game’s best concepts are almost there, the art, outside of portraits and cutscenes and some enemies, isn’t enthralling, and the soundtrack is good, but not a standout among the portfolio of either of its composers. The story is your best bet on staying hooked, as the relationship between Rayard and Callana is a solid foundation for the game, and the layers built on top of it stand tall. Just don’t expect anything revolutionary that’s been hiding in Japan this whole time from the rest of the package.

As for the developer, Wolf Team, this is one of the first games they created in this specific iteration of the outfit. Wolf Team was a studio within Telenet, which published this game (and gets the credit for developing it, too, since Wolf Team wasn’t independent or anything — just a team within Telenet). While Wolf Team had existed since the mid-80s, they had also left Telenet at some point, rejoined later, and then were part of a 1993 restructuring that so many of the long-term members disappear, leaving behind a younger, less experienced group. This is the one folks are likely to be more familiar with, even if they aren’t aware that they are: Wolf Team was the Telenet studio that would develop Tales of Phantasia for Namco.

Wolf Team is and was responsible for the vast majority of the Tales games, but even the Wolf Team known for these isn’t the same as the one that began Tales of Phantasia, the initial entry in the series. That’s because, in the time it took Wolf Team and Namco to work out all of the details of what would become the final version of Tales of Phantasia, a whole bunch of the studio’s members packed their bags and left to form tri-Ace, the studio known for, among other things, the Star Ocean series. If you’ve ever wondered why Motoi Sakuraba seems to have such an affinity for both Tales games and various tri-Ace projects, it’s because he worked with all of those people before either of those series or studios even existed.

Namco would eventually acquire the majority of Wolf Team in 2003, and renamed it Namco Tales Studio, since that’s basically all they were doing, anyway. Telenet would declare bankruptcy in 2007, (Bandai) Namco would scoop up the rest of the shares in the studio, and four years later, Name Tales Studio would no longer exist as an entity within Bandai Namco, but would instead merge completely into it. tri-Ace remained independent for years and years, though you might not have known that based on their history of publisher choices. Enix and then Square Enix handled almost all of it, with the occasional foray into Sega or Konami, and that’s still the case now even though tri-Ace was acquired in 2015 by mobile game publisher Nepro Japan. With one exception, they’re remained a developer for consoles and Windows since, though, they’ve also narrowed their focus a bit, with just Star Ocean and remakes/updates of previous titles their purview in the years since that acquisition.

It would be something if a remake of Tenshi no Uta would release and get some modernizing touches that maybe help it to finish baking and reach its considerable potential, but as basically the entire past of Wolf Team has been forgotten about by their bosses outside of the advent of the Tales series in the decades since the last of these titles, it seems unlikely that we can count on that sort of thing. At least we have the unofficial translation of the original to turn to, and while the game isn’t quite as good as I want it to be, it does have its charms worth exploring if you’re looking for another Japan-only JRPG to try.

One note about the unofficial translation to keep in mind, though: this game won’t easily work like it should on a modded SNES Classic. It opens, but depending on how you fiddle with the emulator options (the default emulator, Canoe, or installed Retroarch), either the audio or the text are missing. Through SNES9X, on both Windows and Steam Deck, the game works as it should, but on occasion the Classic’s emulators have a rough time with patched, unofficial translations of Super Famicom games, and Tenshi no Uta is one such game.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.