Past meets present: The Tower of Druaga

A highly influential and popular Japanese arcade game that helped launch action RPGs, a sense of community and teamwork in arcades themselves, and has been completely misunderstood elsewhere.

This column is “Past meets present,” the aim of which is to look back at game franchises and games that are in the news and topical again thanks to a sequel, a remaster, a re-release, and so on. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

There is a straight line you can draw between Namco’s 1984 Japanese arcade hit, The Tower of Druaga, and a modern Game of the Year recipient like From Software’s Elden Ring — and it’s a much shorter line than you’d imagine. Druaga is an early action RPG and dungeon crawler — nascent, even — full of easy deaths and secrets you have to dedicate yourself to unearthing, or you’re not going to have much luck climbing the titular tower. Its design has been described as “oblique” by numerous critics, and it’s certainly more opaque than transparent, but Druaga doesn't hide any of its secrets any more than From does their own in their Souls games (including 2022’s Elden Ring, which Bandai Namco themselves just happened to publish): like in those beloved modern masterpieces, you just have to work it out for yourself over time or with an assist from hints, and try something else when you end up sprawled out on the floor instead.

From’s Souls games have, as part of their communal backbone, the online message system that allows other players to leave words of wisdom or warning for other players to find in their own travels in Boletaria, Drangleic, The Lands Between, and so on: Druaga, in a pre-internet world, helped solidify the practice of leaving shared notebooks at arcade cabinets, filled in by hand with hints by everyone who had played the game to aid the next players in their own quests. Given how From is, and their obsession with going back to a particularly brutal era of role-playing game design powered with today’s technology, there’s little chance that this common thread was accidentally sewn into the fabric of Souls.

The Tower of Druaga was influential in ways that are easy to trace without being directly told so by those it influenced — see above — and certainly helped pave the road for Falcom’s Dragon Slayer, which would release at the end of the summer of ‘84, a summer that had begun with Druaga’s own June debut. It’s not just action RPGs that took from Druaga, though: Nintendo’s The Legend of Zelda was an action-adventure game, not an action RPG depending on who you ask, but the emphasis on puzzle solving and dungeons and figuring out secrets largely through experimentation? Series creator Shigeru Miyamoto didn’t get those ideas from out of nowhere.

In fact, in an interview published in the February 1986 issue of Japanese magazine Famimaga, Miyamoto even spoke to the creator of Druaga, Masanobu Endo, about his love for the game (translation courtesy shmuplations):

Endo: I have to say, there's no two ways about it, Super Mario Bros was the most interesting game last year. It's no contest.

Miyamoto: Well, I'm a big fan of Xevious and Tower of Druaga myself. We had them bring an arcade cabinet to our office, and I played Tower of Druaga on it. But I couldn't get past floor 60… I got sent back to floor 14 and couldn't end up finishing it. Still though, the maze programming is excellent, as I've come to expect of Namco. It's impressively well-made.

The first Legend of Zelda game, by the way, would release the same month that interview published. It’s not like Zelda pulled everything it was from Druaga by any means — it might have used some of Druaga as a foundation but clearly was its own foundational, influential title that changed the industry — but it’s difficult to avoid the conclusion that Miyamoto took a fancy to it that ended up showing itself in his own work. And we don’t have to infer as much from that interview, either: Miyamoto himself has admitted that the initial The Legend of Zelda prototype resembled something more akin to The Tower of Druaga than it did to the finished product.

Originally, before it was even thought of as “The Legend of Zelda,” it was a series of dungeons located underneath the Death Mountain range… a dungeon crawler, rather than an open-world game. According to a translation of the initial Japanese edition of Hyrule Historia, Miyamoto and company eventually wanted to go beyond the dungeons and “feature a world above, so we added forests and lakes, and so Hyrule Field took form gradually.” (The North American edition of Hyrule Historia, for whatever reason, words all of that far more succinctly and with less detail, but the general thrust is the same.) Thus the marriage between Miyamoto’s love for the Druaga-style game, and the story we’re used to hearing about Zelda springing from his childhood memories of playing outside in nature, resulted in The Legend of Zelda as we know it. Not a bad thing to take even partial credit for inspiring.

All of this — the game’s lineage, the influence on and connections to other beloved games, The Tower of Druaga itself — were all lost on North American audiences, however, and it’s because Namco’s arcade hit stayed in Japan. It was ported to a number of platforms there, from Japanese computers like the MSX and FM-7, to home consoles like the Famicom and PC Engine, and it spawned a series of arcade and console sequels as well, but all of that stayed in Druaga’s country of origin. Which meant that, by the time The Tower of Druaga finally did receive a standalone international release in 2009, those international critics had no idea what it was they were playing.

They weren’t aware of the game’s history, its importance, or exactly what it even was, in terms of how to play it. They had no connection to how it was meant to be experienced, the communal aspects and the mysteries to be solved that made it such a hit to begin with, and instead treated it as a dated chore that no one in their right mind could possibly enjoy. A series of 3/10 and 4/10 reviews were published shortly after Druaga released as one of the first four Virtual Console Arcade titles on the Nintendo Wii, and the most unwilling to entertain why anyone would enjoy it likely came from IGN:

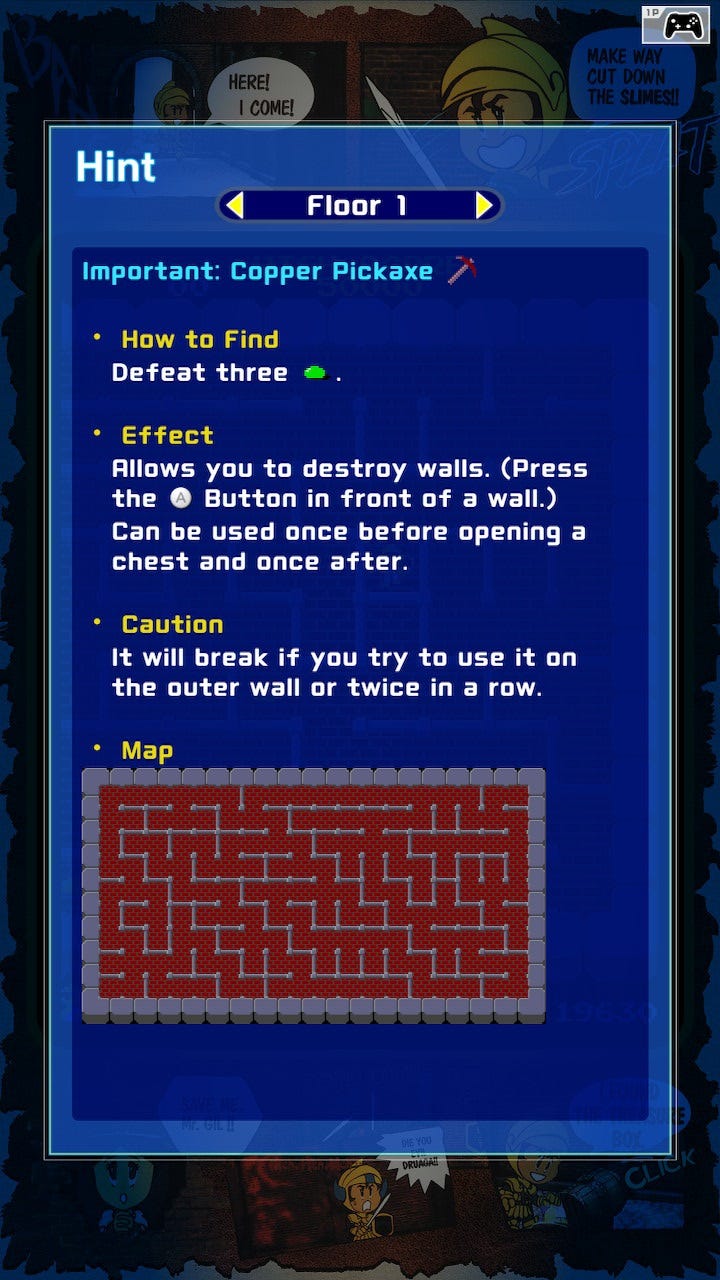

The Tower of Druaga did the same thing, 10 years earlier -- it could only be completed by those gamers dedicated enough to memorize all its patterns and secrets. Newcomers wouldn't have a chance, as they wouldn't know, for example, that you have to kill three Green Slimes on Level 1 to make the Copper Pickaxe appear. Or that the it's two Black Slimes to defeat if you want to earn Level 2's Jet Boots. Or that Level 29's Golden Pickaxe (an improvement from the Copper one, of course) isn't activated by any accomplishment in the labyrinth at all -- you instead have to spin the joystick in a circle three times.

…

So this is a game that, in the end, is absolutely unplayable unless you just happen to be one of the five individuals in America who actually still remember all the secrets to this 25-year-old coin-op, or you make use of an FAQ or Walkthrough that you can constantly reference to make sure you're not missing anything (which is a painfully un-fun way to play any game).

…

The Tower of Druaga is, to me, woefully boring and pointless to play. It's slow-paced and not much fun even on the surface, and digging deeper than that just boggles the mind -- its extreme over-complication, with its tons of hidden collectible treasures and the associated random requirements for finding them, is just not what you want in an arcade maze game.

As you probably already figured out yourself, newcomers to The Tower of Druaga in Japanese arcades did “have a chance,” thanks to the proliferation of notebook sharing and the communal aspects of playing this single-player experience. Which American could “remember” all of the secrets to the 25-year-old game, when it hadn’t actually released in American arcades? (This review also described its North American run as a “flop,” which, again, what run?) Sure, it had released as part of a couple of collections, but if anything, that’s even more reason to give it this standalone release 25 years after the initial one, to help launch a service: it’s a legendary game, but outside of Japan, no one knew the legend. And that only became more clear as people paid to review video games showed a complete lack of contextual knowledge about Druaga’s past, its influence, and why it might be one of the inaugural releases on a Nintendo-branded service.

Critics in 2009 did not understand it, and given the pressures of reviewing those Virtual Console titles as quickly as possible following their release — there were multiple VC releases weekly, some of them obscure by North American standards like Druaga, and the expectation was that sites like IGN would handle that influx of “new” releases alongside the actually new ones of the day — they likely didn’t have time nor the desire to give the time to understand it. But Druaga is a game with history that is itself a major part of gaming’s history, and to just toss it aside as poorly designed, or decry it for being something only “dedicated players” would enjoy, as more than one review put it, is shortsighted, incurious, and missing the point of what its sudden appearance as a standalone offering for the first time, 25 years after its initial release, could have meant.

That it arrived in North America the same year that From brought us Demon’s Souls — one month after its Japanese release and around six months before its North American debut — a game Sony published as a major holiday exclusive for the Playstation 3… well, the contempt for Druaga was a bad look then, and it’s aged much worse than Druaga ever did. If anything, we’ve seen a renaissance in this particular style of game design, between the rise of Souls games and dungeon crawlers and roguelikes and so on: Druaga, to this day, fits right in with the games and genres it helped to inspire.

Part of a critic’s job is to bring context to the reader, and dismissing Druaga basically out of hand because it gave you a hard time when you first opened it up, and you didn’t have the time to go beyond a surface-level examination of it, is a failure to do that job. Druaga is too “slow,” with protagonist Gil not walking nearly fast enough, as multiple reviews pointed out? The upgrade to move significantly quicker is on the literal second floor of 60: it appears if you defeat two of the new enemy type that shows up in that level, which someone with even a modicum of curiosity would attempt. It’s one of the easiest treasures to accidentally stumble upon, but you have to give yourself the chance to stumble. While I can understand the desire for a game to reveal itself to you immediately, I don’t have to empathize with that desire.

The point here is not to attack these individual reviewers for how they handled Druaga’s Virtual Console release, though. Instead, it’s to point out that the nature of the review machine — churn them out fast (no, faster!) — made doing the kind of work readers deserved difficult, which in turn made critics look worse than they would have been if they had space to work things out. I imagine more than one of those reviewers who gave Druaga a 3/10 or whatever would have handled their review far differently if they had been given the space to answer the many questions they had about why in the hell Japan loved this game so much in the first place. They didn’t have that time, though, and readers, who, especially in an age before there was a mass proliferation of indie video game criticism sites that would be able to expend more effort and attention on answering these questions, were left in the dark and told to avoid Druaga, based on the consensus recommendation that it wasn’t worth the $5.

Now, to the credit of everyone reviewing the game in 2009, it was the original arcade release with none of the kind of tweaks or adds that had come to it in previous releases over the years. The edition of The Tower of Druaga that released on the Playstation’s Namco Museum Vol. 3, for instance, included a hint system to help players along, since they weren’t playing the game in an arcade with notebooks capable of filling in those blanks. The Game Boy port of Druaga no longer made Gil’s hit points hidden, so you could tell if going after a particular enemy with the game’s bump combat system was a good idea or a guaranteed way to die. The PC Engine edition showed Gil’s hit points, too, removed the timer, and added a system of upgrading health, power, defense, speed, and the number of times you could use the wall-breaking pickaxe on a given floor — you just had to find a blue crystal on each floor in order to do so.

The Virtual Console edition, though, was lacking any of those little improvements and quality of life adjustments… but that’s also a subject that could have been tackled by the reviewers themselves, with the framing being that this particular release of Druaga was only going to interest a very particular kind of retro gamer, and was missing some of the improvements and tweaks made to the game over the years. Instead, what we got was mostly an attack on the concept of Druaga itself. Again: context.

Endo himself was surely in favor of the tweaks made to Druaga to make it a bit more approachable. As he told Beep! Magazine in 1985, “I’m glad that Tower of Druaga was loved by fans, but the fact that the game made players more paranoid about looking for secrets, and that it put a new emphasis on ‘clearing’ a game are two consequences I’ve had time to reflect on. Was it really setting a good example for other games…?” The “clearing” part of things might require some background: Druaga was an early example of an arcade game with a clear beginning and end; Xevious, Endo’s other ridiculously influential arcade hit, could essentially be played forever on one credit if the player was good enough. So, Druaga received Endo’s solution to that problem: “Arcade games would loop endlessly if you didn’t die, so I wanted to create a real ending that would act as a forced stopping point. I thought that if the ending tied into the story and gave the player a sense of completion and achievement, then no one would mind.”

Endo’s feeling was certainly not off base, though, as mentioned above, he did seem to regret the focus on clearing that grew out of it. That being said, “On the other hand, thanks to Druaga, the community and culture of notebook sharing (where arcade players shared their secrets and tips) was born, so that was a good thing.” Understanding that people playing at home wouldn’t have the same experience as those in a more communal setting led to the built-in hint systems and some of the hidden bits like hit points being revealed — if the PC Engine version of The Tower of Druaga had released internationally on a platform as popular as the SNES, the franchise might have had a far different legacy by 2009 outside of Japan than it did.

The Tower of Druaga remains highly enjoyable to this day, whether you’re in Japan playing it or not. And thankfully, you no longer need to be there or stuck digging up a semi-obscure collection from decades ago to play it in the present. The arcade edition of The Tower of Druaga is included in the Switch and Playstation 4 Namco Museum collection, and it’s easily its definitive at-home edition: there are online leaderboards, a rearranged and restriction-filled challenge mode for people who somehow don’t think the original Druaga was tough enough, and a hint system that not only tells you how to get every item on each floor, but also provides an explanation of what the item is for, how necessary it is, and, in some cases, how you’d accidentally use it, lose it, or break it. I’d say this is all a response to how it was received internationally in 2009, but again, Druaga had already begun incorporating built-in hints and quality of life changes decades before then.

Now, how you go about playing Druaga should probably be explained. There are 60 floors, and each floor is a contained level. You play as Gil — short for Gilgamesh — in this Babylonian-inspired game. The Tower of Druaga is actually the Tower of Babel, only after it had been destroyed: it was rebuilt by Druaga’s dark magics, and filled with monsters. Gil is a knight seeking his lost love, Ki, who is no damsel in distress: she just happened to be kidnapped by the powerful and evil Druaga atop the tower, which she climbed all on her own prior to Gil’s entrance. (We know Ki isn’t helpless, too, because she stars in her own prequel game on the Famicom — The Quest of Ki — and in the sequel to The Tower of Druaga: The Return of Ishtar.)

Gil holds his shield out in front of him by default — it can block magic beams directed right at him. When you want to use your sword, the shield is held to Gil’s left, which means unsheathing it doubles also a defensive move: magic beams coming from Gil’s left can be blocked this way. You don’t swing your sword so much as run into enemies with it, Ys-style. You have to make sure you time things right, so your sword is actually in front of Gil, and try to avoid running into enemies who are moving toward you at the same time when you can: you’ll cut right through a slime who is just standing there, for instance, but might take some damage if it jumps into you at the same time you’re walking toward it.

Each floor has a secret treasure, some more important than others. The design might seem “oblique,” but again, the point was to figure out what was right and what was wrong, what could be missed and what had to be collected. You don’t “need” the boots that make you go faster, but if you want to be able to get out of the dungeon as fast as possible, to avoid encounters when you can and to get a higher score, then you should be sure to get them, even if it means restarting the game until you clear floor two with them in tow. Here’s a look at Floor 3 of Druaga in the Famicom edition of the game, which is available on the Switch through Namco Museum Archives Vol. 1:

Gil defeats a Blue Knight, which reveals a treasure chest. The chest has a potion inside which will revive Gil once without it costing him an extra life. Gil then exits the stage a little quicker due to the use of the pickaxe to take down a wall in his way: the pickaxe can be used once before the opening of a chest, and one more time after a chest is opened: don’t try to use it consecutively or on an outer wall, or it will break. Notice the decreasing five-digit number in the bottom-right corner? Those are the possible bonus points you can receive after completing a given floor. Whatever number is still there when you finish is the number of points awarded: if the bonus points run out, a 60-second timer begins to tick down, and to make things worse, some fast-moving energy balls start hunting you down. Just one more reason to have the pickaxe and boots handy, so you can make it out of a stage alive quicker.

Some items might be optional, but you can’t defeat Druaga without the Blue Crystal Rod, and some treasures, like the White Sword, are required for additional treasures to appear on later floors. Don’t be shy about using the hint system: hints are a significant part of the Druaga experience, and you still have to actually pull off whatever it tells you that you need to do in order to cause a chest to appear. Sometimes it’s better not to grab the key right away, lest you find that the only way to a chest is through the door that will now unlock, open, and send you to the next floor. You have to both move and react quickly, but give yourself time to strategize. It’s kind of incredible just how much depth exists in this coin-op from ‘84, but if you take the time to find it, it’s plainly there.

The Tower of Druaga maybe isn’t for everyone, in the same way that Souls games — well, Elden Ring’s 20 million sales aside — haven’t been for everyone, in the same way that Etrian Odyssey remains popular within its niche, but still niche. A game doesn’t have to be “for everyone” to have merit, though: The Tower of Druaga was a masterclass of its time, and remains intriguing to this day: its secrets beckon, and the desire to unearth them is strong enough for you to let it overtake you. It’s at its most playable in its at-home form right now, as playable as it’s been since it was a communal arcade hit in the 80s in Japan, and is available through the aforementioned Namco Museum collections, as well as through Hamster’s Arcade Archives series.

It’s one of the most important games in the industry’s ever-growing history: one that influenced developers from Nintendo, Falcom, and more, that spawned a series of sequels, a Mystery Dungeon spin-off, an anime, and has found itself re-released again and again even after an entire continent’s worth of reviewers failed to understand what made it so popular in the first place. Give it a shot, if any of this sounds of interest to you: it’ll take time and effort to master, but that will just make completing the game that much more satisfying… just like Endo intended nearly 40 years ago now.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

Thanks for covering this! I grew up with this game, as far as I can remember nearly 20 years it's been (I was probably about 5 years old) played it on my PlayStation. It's such an amazing game, yet underrated story but the deeper you go the more you understand its lore. Hard to believe it's been 40 years since its release and to this very day I'm still supporting it, I try to get my hands on as much "rare" merchandise as possible, including any re-releases of the original game and its sequels.

Apart from being the Action-RPG title that it is, it's no wonder how Namco continues to take inspiration and put that into their modern games such as Elden Ring and Dark Souls like you said, even if they haven't made any remakes or revivals, but hopefully something comes up - I'd imagine Namco brings it back so that both returning players and newcomers try out their newer version on this game, even if it doesn't happen, I won't give up my hopes just yet, maybe a museum compilation like they did with Pac-Man Museum+ then perhaps more people would appreciate this game.

You ever considered looking at it's brother game Dragon Buster. It was just as influential for being not just an ARPG, but an action game with an expansive moveset. It's also still fun to play today.