Ranking the top 101 Nintendo games: No. 19, The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening

Link's Awakening was the best thing going in 2D Zelda even before its excellent Switch remake.

I’m ranking the top 101 Nintendo developed/published games of all-time, and you can read about the thought process behind game eligibility and list construction here. You can keep up with the rankings so far through this link.

Most Zelda games don’t present a very involved or detailed narrative. That’s not to say that these games lack a story: it’s just that said story tends to be presented more through themes and exploration by the player that feeds their imagination than they are explicitly told to you through dialogue or cutscenes. There are exceptions, like Twilight Princess, which goes heavy on the narrative aspects and links Ocarina of Time to its own story, but usually, Nintendo tends to be a little more subtle and let themes and exploratory world-building guide the narrative more than dialogue.

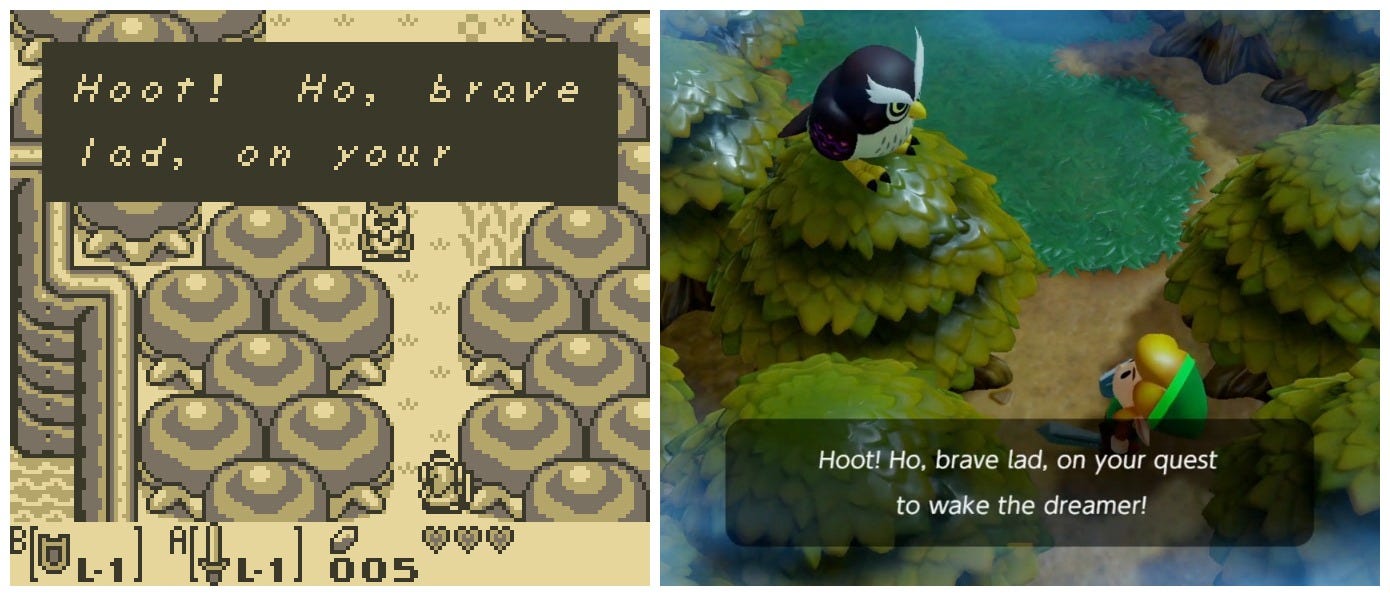

One of the two Zelda games in which this setup is most apparent — and most successful — is Link’s Awakening. Originally released on the Game Boy in 1993, it took aspects from the original Legend of Zelda for the NES and combined them with some of the gameplay from its more direct sequel, Link to the Past, to create something new. Something that, thanks to its themes and design, remains the best 2D Zelda out there to this day.

Here’s the thing about Link’s Awakening: even if it had not received a remake on the Switch that refined some of the gameplay by making use of the additional button inputs, even if it didn’t end up on a high-definition console with a stunning, updated art style, this is right around where it would have been in the rankings. It’s the pinnacle of Game Boy games, and only held back by entry we’ll get to on this list later, Link’s Awakening is the second-best Game Boy Color game, too. The updated release of it numbers among the very best things you can play on the Switch, whether you’re putting it up against the system’s originals or its retro channels or its many ports. It’s one of the greatest Zelda games, 2D or otherwise, and one of [checks spreadsheet] the top-20 games Nintendo has ever released.

Another way of putting this is that there is a reason Nintendo put a previously handheld Zelda on the Switch, and it’s not just because it’s a hybrid system that can serve as a handheld. The Switch sells games at console pricing, not handheld pricing, and no one worth listening to is going to argue against Link’s Awakening being worth the former in an updated form. It was a stunning achievement for the Game Boy, which had plenty of titles that very obviously rose above the unfair stigma of handheld gaming being a lesser experience, but none more so than Link’s Awakening. If anything, Link’s Awakening maybe could have been more of a success, in a vacuum, if it had released on the Super Nintendo as the sequel to Link to the Past that it is — the two games feature the same iteration of Link. There was something to the idea of populating the Game Boy’s library with such a high-end release, though, and it probably made Nintendo a lot more money in the long run to put Link’s Awakening on their handheld behemoth, in a space they thoroughly dominated the competition in and wanted to ensure they kept dominating, than to use it as a single blow in the fight for market share against the Sega Genesis.

It’s hard to say how things would have played out if Nintendo had put Link’s Awakening on the SNES alongside Link to the Past, but it’s also hard to argue with the success found in reality: Link’s Awakening sold nearly 4 million copies on the Game Boy, another 2.22 million on the Game Boy color in its DX form, and then nearly 340,000 more on the 3DS’ Virtual Console. Sales for Game Boy systems went up 13 percent in 1993, the year of Link’s Awakening’s release: this is no small thing, given the system was already four years old at that point. It was exactly the kind of release that allowed Nintendo to keep that system going for just shy of a decade before introducing its replacement in the Game Boy Color, though, and that has real, long-term meaning, especially given how many upstart handhelds with superior graphics and screens the Game Boy vanquished in its day.

I don’t usually like to talk sales here, since sales don’t necessarily equal quality and all that, and we’re using this project to focus on quality exclusively. I do, though, think that in this instance, sales and what Nintendo wanted to use Link’s Awakening to achieve are instructive. They knew they had a killer idea, and then they knew they had a killer game, and they put it on the Game Boy even if it “felt” like a console release, because from a business perspective, that was the smarter play. Link’s Awakening eventually ending up as a console game without anything besides quality of life changes to the core experience and game play should not be a surprise: it was always that “level” of game, regardless of its initial home.

Nintendo didn’t remake Link’s Awakening to match up with other Zelda titles that came after, in the way Square Enix overhauled Nier’s gameplay with Nier Replicant in the wake of the success of its sequel, Nier Automata. You don’t have to go to the item screen in Link’s Awakening as often as you used to in the past, because you have dedicated buttons for the sword and shield now, and, outside of dungeons, the map isn’t broken into a grid that you visit one square at a time anymore. It also, obviously, looks significantly different stylistically, as it has its own unique art style now, but it still looks just like Link’s Awakening did nearly 30 years ago, in the sense of what it is you’re looking at. It’s just rendered in a different style. The one addition they made to the Switch game — the dungeon builder — is the worst part of the entire Link’s Awakening experience. It’s optional, though, so whatever.

It’s the same game it has always been, which is to say, it’s one of the best games Nintendo has ever made.

Much of the setting of Link’s Awakening is unique, which helps it stand out in a sea of Zelda games. The game takes place in a dream, which isn’t a spoiler, really, considering the bosses you fight are called “Nightmares” and the game is literally titled “Link’s Awakening.” Dreaming makes it so there doesn’t need to be an explanation as to why there are Goombas to be stomped by Link, or why there are another of Mario’s classic foes, Chain Chomps, and also why the Chain Chomps seem to be domesticated pets. And yes, “stomped” is accurate, as Link is able to jump when he equips the feather, and jump on enemies like Goombas like he’s in a sidescrolling platformer during certain segments of dungeons, too.

The surreal nature of it all goes beyond just “ha ha there are Goombas in a Zelda,” of course. The dream-like experience is fueled by the game’s enemies, sure, but also its music — the original soundtrack is so very Game Boy, and so, so good, which you’ll be reminded of if you open the video embedded above — and parts of the setting itself. Why are there telephones in this Zelda? How is a magical creature like the Wind Fish, which is neither of those things, keeping Link trapped on this island simply by sleeping? How is there an entire village of talking animals that live in homes like “normal” people? The Switch release also adds a little graphical detail to the borders of the screen, making everything look a little more dreamlike out on the margins, which fits, because again: it is a dream.

The actual spoiler, regarding the dream thing, is who is having the dream: it’s not Link. And this little detail isn’t actually that little, as it completely changes the meaning of Link’s actions, and the weight of what it is he needs to do. It’s one of the only times that you can argue Link is selfish instead of selfless throughout the entire Zelda canon, and it poses a philosophical question that I spent an hour talking to Trevor Strunk about on his No Cartridge podcast when the remake hit stores in 2019. It’s not that Link will awaken when the Wind Fish does, ending the dream: it’s that the Wind Fish has dreamed up the entirety of Koholint Island, and all of its inhabitants. They are all real to the touch, as real as Link, but they are creations of the Wind Fish’s magic. They have lives, they have homes, they have backstories, they have existed for untold time having children and growing and loving and dying within this dream, which to them, is indistinguishable from reality. Because the dream Link finds himself trapped in is reality. And his escape will end these lives, this existence, for everyone except for himself, who belongs outside of this dream reality, and the Wind Fish, who should probably be more responsible about his ability to haphazardly create worlds while catching some shuteye.

Link ends up connected to the Wind Fish’s dream when he is shipwrecked: he is actually dozing, or more accurately, probably in a knocked-out state, hanging on to a broken part of his ship at sea, and this sucks his consciousness into the world the Wind Fish has dreamed up. Nightmares have arrived, seemingly at the same time as link, to keep the Wind Fish from ever waking. Monsters appear in greater numbers, the creatures that already existed in the world become restless. Link’s arrival has doomed Koholint, which will eventually be overrun: his decision to leave the island dooms it even sooner. Link could have defeated the Nightmares and stopped the threat of the monsters, and let the Wind Fish wake on his own, if the creature was ever to wake again. Link could have lived out the rest of his days on Koholint and had a fulfilling life with the villagers who accepted his arrival with grace and kindness, but he chose a return to his own world. Which is understandable, sure, but his decision blinked a world out of existence, a world full of people as real, with as much right to exist, as Link had.

This is what I mean by Zelda games relying on themes to tell their story: none of this is necessarily explicitly told to Link, but the implications are all there, the weight of Link’s decision and the consequences of it laid out before you in a recognizable fashion even if your talking owl pal doesn’t spell it out as bluntly as this. That Link makes these choices, that he decides to erase a world from existence to return to his normal life, still haunts me when I play to this day, and I’m not some newcomer to Link’s Awakening: I had the thing on Game Boy when I was a kid. Zelda games are often at their best, narratively and thematically, when expectations are subverted. Link’s Awakening was just the fourth Zelda game, but even with that in mind, it subverted expectations on a number of levels, including with its themes. All this time later, it still stands out for this, because Nintendo has never tried to develop another Zelda just like it. It gets to stand on its own, and stand it does, as strong today as it was back in 1993.

As for the actual gameplay, which is maybe why some people play a Zelda rather than to be haunted by the idea that Link murdered an entire island of people because living there was inconvenient for him: the dungeon design makes it more of a successor to the original Legend of Zelda than to Link to the Past, as it’s a very one room at a time setup, but with plenty of advances in design philosophy (and graphical prowess) that help give the dungeons and their rooms more character, more personality, more distinguishing characteristics than the extremely basic version of a Zelda dungeon that the original game possessed. It helps, too, that the items available to you are so different than they had been to this point: much of what you utilize in Link’s Awakening became kind of handheld Zelda staples, but they became staples because they worked so well the first time around.

The dungeons range from very straightforward to the kind of places that can trip you up, and the latter can be a real problem considering that the original versions of Link’s Awakening don’t let you use fairies to revive yourself: instead, you pay to be slathered in an oil that will give you a one-time revival, and you don’t want to accidentally use it up before the boss fights. The Switch version of Link’s Awakening does let you carry up to three bottles, and to carry fairies within them, but they still don’t revive you. They are solely to be used like the healing potions from other Zelda titles, a manually selected and used item for replenishing health. This is the kind of change I can get behind, since they didn’t drastically revamp the game’s balance by adding in fairies and bottles, so much as add in an option you can use if you want to. If you want to experience the original game’s challenge but with modern graphics, just don’t put fairies in the bottles.

And even if you’re just using them as if they were a health potion, that mostly just saves you from having to enter and exit and reenter a room with breakable pots that have hearts in them, which you know you absolutely did to load up when you had the opportunity.

The world is a more intriguing one than Link to the Past’s, owing much in part to the cast of characters you interact with as well as the unique features of Link’s Awakening that have already been referenced. It’s not quite as complicated of an overworld as that of the Oracle games, and it lacks the degree of backtracking that is one of the few flaws in Minish Cap. The world is not multilayered, nor are there two sides to it or multiple points in a timeline. Outside of it not being as open-ended as the original game, it truly is its successor for this direct kind of approach and explorable world, and remained its most obvious one until only very recently in Zelda history. But we’ll talk about that another time. Just know that the relatively straightforward nature of the overworld of Link’s Awakening is one of the game’s strengths, as it helps you focus on the strong dungeon design and the characters that populate the world, while still allowing you the freedom to discover odds and ends and sidequests and hidden goodies with the kind of regularity you expect from a Zelda title.

There’s the item trading quest, which is full of weirdness and laughs. There is the man who tells he’s going to be lost later and where, so that you make a mental note of looking for him when it seems appropriate to do so. There is the shop that will let you steal exactly one item without paying before the shopkeeper retaliates by smiting Link with lightning the next time and every time after that he enters the store: you better make sure that theft was worth it. So many little gems like this to be discovered and enjoyed, despite the relatively small world, size-wise, we’re referencing. It’s filled to the brim with personality to compensate, and is a significant part of why Link’s Awakening has always felt “bigger” than its home system.

It’s a classic, one I can and have gone on at length about. If you don’t want to pay for the Switch version, then grab a copy of either the original Game Boy edition or the Game Boy Color one, that has not just colorization but also additional dungeons and a later choice between either an armor upgrade or a sword upgrade (the Switch version of the game also has this content). The Switch one is absolutely worth it, though, not just for quality of life upgrades, but because it’s a truly gorgeous game to behold. You can certainly enjoy Link’s Awakening without playing it in its modern incarnation, though: I played through it twice for the purpose of this project, once with the DX edition and once with the Switch one, just to be sure I was on the right track thinking they were comparable. If you haven’t felt the need to experience Link’s Awakening before, whether because you don’t prefer handheld games or think that kind of Zelda is somehow lesser than its console cousins, well, this, more than any of those games, is the one that would prove you’ve been off base. That’s why it’s the one Nintendo gave a handheld-to-console conversion to first, and why you should see what all the fuss has been about for 28 years now.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

I hadn't ever considered it but the dream of another creating the reality the protagonist explores seems to have been borrowed in Final Fantasy X with the dream of Zanarkand by the Fayth. Tidus starts out selfishly living however he wants and then, once he understands the nature of his non-reality, he works to undo it to release those dreaming