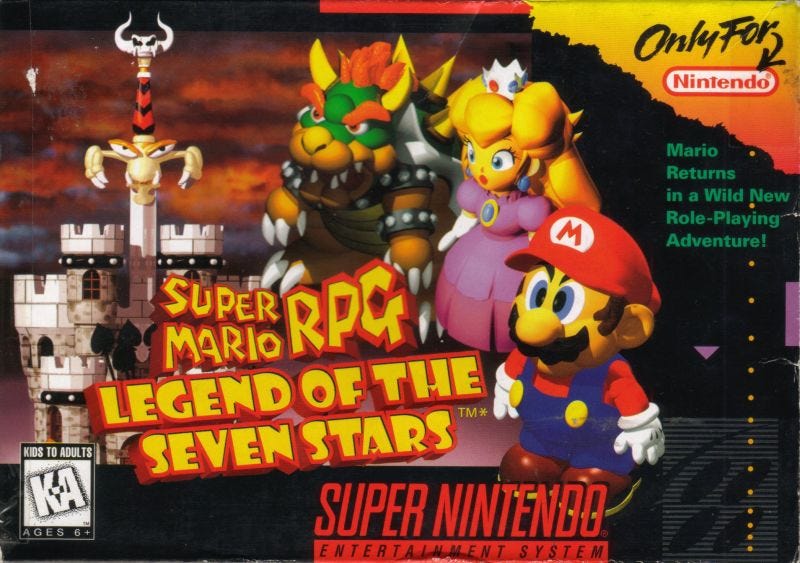

Ranking the top 101 Nintendo games: No. 76, Super Mario RPG: Legend of the Seven Stars, and no. 75, Paper Mario

Nintendo got into the RPG business with their main man, and didn't let a little thing like the developer of that game leaving to make Sony games instead keep them from continuing down that road.

I’m ranking the top-101 Nintendo developed/published games of all-time, and you can read about the thought process behind game eligibility and list construction here. You can keep up with the rankings so far through this link.

It’s difficult to not pair Super Mario RPG: Legend of the Seven Stars with Paper Mario, which might as well have the same subtitle. They’re very different games in many respects, but Paper Mario is also technically a reboot of while also technically being a sequel to Super Mario RPG, which muddies the waters just enough to keep you from seeing either clearly as their own, distinct title in a zoomed out scenario like the one that fuels this ranking project of mine.

You see, Super Mario RPG was developed by Square for the Super Nintendo, and is Mario’s first foray into the RPG space. The relationship between Square and Nintendo soured shortly afterward, though, with Square bringing their previously Nintendo-exclusive Final Fantasy series to the powerful (and disc-based, cheaper to develop for) Playstation and, at least temporarily, severing the ties between the two longtime partners. So, Nintendo was left with a good, successful idea — Mario, but in an RPG — and no one to develop that idea further. At least, that was the case temporarily: the task was eventually handed to an internal Nintendo developer, Intelligent Systems, who had found success in Japan with the Fire Emblem and Wars franchises, as well as helping out on some all-time titles like Super Metroid. The result? The Paper Mario franchise, which began in 2000 on the Nintendo 64 with Paper Mario, and just released its sixth title in the series, Origami King, in 2020.

The Paper Mario titles are certainly of a varying quality — you will find just two of them on this top 101 list — but there is only one title in the series that I feel comfortable saying isn’t a fun game, and that’s the 3DS entry, Sticker Star. The Wii U’s Color Splash has brilliant writing that helps overcome some of the monotonous issues with the battle system; Super Paper Mario almost never knows when to stop showing you dialogue boxes so you can just get on with it, but you want to get on with it because the gameplay itself is a lot of fun. Origami King suffers from the same edict to avoid too much new story or new characters that Intelligent Systems has had to work around for some time now, but it’s also considered something of a return to form for the long-running franchise. Or, at least, a game pointing in the right direction.

All of this began with Paper Mario in 2000, but it also began in 1996 with Super Mario RPG. There might not be a Paper Mario if not for Square nailing Mario In An RPG as well as they did, and there wouldn’t be a Paper Mario franchise if Intelligent Systems hadn’t similarly created an instant classic when it was their turn to give that very thing a shot.

The stories aren’t the same, not exactly, but the base inspiration matches up a little too well, to the point where Paper Mario, as I said, is something of both a sequel and a reboot. The main difference in these titles, which are both platformers with turn-based battles and RPG leveling mechanics, is in who Mario is fighting: in Super Mario RPG, creatures from another dimension arrive, take over Bowser’s keep, begin to spread throughout the entire Mushroom Kingdom (and beyond), and it forces Mario to actually team up with his longtime nemesis Bowser in order to push these invaders out of their realm. These baddies, led by brand new character Smithy — named such because he’s actually some kind of Blacksmith King who has smithed himself an army of minions — crash into the Star Road on their way to taking over Bowser’s castle, which scatters star pieces across the land. These star pieces, comprising the Star Road, granted the wishes of the populace. With no star road, wishes aren’t being granted, and quality of life is dropping in ways besides “there is an army of evildoers made by a robot blacksmith king bent on world domination” because of it.

In Paper Mario, it’s Bowser who Mario is saving the Mushroom Kingdom from. Once again, you are collecting stars in order to allow wishes to once again be granted, but this time, it’s because Bowser and his minions stole the stars, all of which are now sentient and have personalities. Mario defeats Bowser’s underlings in a variety of locales, liberates these stars, and grows his own powers in the process, with the end result being he has the power of their wish-granting as both sword and shield to tackle Bowser, who, as he does, has managed to find a powerful magic to grant him the strength to defeat Mario once and for all.

The lands you traverse in each game are very different ones, with Super Mario RPG including plenty of Marioverse characters — Goombas! Koopa Troopas! Yoshis! — but also creating brand new ones, like your party members Geno and Mallow. Thanks to his adoption by a frog, Mallow thinks he’s a tadpole, even though he is a cloud person wearing pants who can summon lightning, while Geno is an action figure slash doll inhabited by a spirit creature from the Star Road, grown to person size in order to fight back against Smithy and his gang alongside Mario. You create a party of three, always featuring Mario and two others from Mallow, Geno, Bowser, and Princess Toadstool: she wasn’t referred to as Peach just yet. In a fun twist on her always needing to be saved in other Mario titles, with the right equipment, the Princess is actually the most capable character in the entire game. You’ll do just fine if you wanted to partner Mario with newbies Geno and Mallow, though, but there is something pretty fun about having Mario, Toadstool, and Bowser all work together against the people who interrupted their usual dynamic.

Paper Mario is almost strictly a Mario experience. You travel to new lands not seen in other Mario titles, sure, but it’s basically all part of the larger Mushroom Kingdom, with more typical Marioverse inhabitants for the most part. Your party is different, too: you build out a large assortment of helper characters, but you can only use one at a time, and they are all clearly inferior to your main character, Mario: any damage they take knocks them out for the next round, whereas Mario has an HP meter and is only temporarily knocked out by specific status effects. With these characters, it’s more about who you are facing in battle or what kind of environment you’re in that will determine which one you’re using. Need info on how to defeat a specific enemy? Use Goombario, who has the power to basically fill out your monster codex. Want to attack multiple enemies at once? You can use Kooper the Koopa Troopa for a spinning shell attack, or, if you need something a little more explosive, there’s Bombette, the class-conscious Bob-omb.

No, really: someone or someones at Intelligent Systems loves to use Paper Mario as a way to air their grievances with the ruling class and promote the plight of the working class, and it endlessly fascinates me that this is the specific space in which that commentary ended up:

Super Mario RPG tried to show you what else was out there besides the Mushroom Kingdom that we knew of, which is how you come to a mine in a mining town inhabited entirely by mole people, or the sky kingdom with the cloud people, or the talking frogs in the pond, or Booster’s… whole thing. Paper Mario, on the other hand, tried to show you more of the Mushroom Kingdom and its inhabitants, to enrich a game world that had plenty of space to be enriched, to flesh out the characters and, ironically or unexpectedly or both, give them layers and make them multidimensional in a game where the characters were all two-dimensional in a 3D space. Hence, the class-conscious Bob-ombs, who aren’t all thrilled about working for Bowser and his minions, who feel that they are essentially prisoners performing forced labor for their Koopa masters. Again: no, really:

Both games are entertaining, they’re funny, and they achieve much with the space they’ve chosen to work with, but I prefer Paper Mario’s deeper, more thoughtful analysis of its game world and the developer’s decision to bring breadth and depth into the inhabitants of the Mushroom Kingdom, whether you traditionally consider them to be good or bad guys. It’s why, all this time later, the original Paper Mario still stands out as one of the best titles in the franchise: the way the game world and its inhabitants are presented and revealed to you, combined with the game’s actual mechanics, is nearly unmatched in the franchise’s nearly 20-year history.

Speaking of battles, they are similar, but different, too. Super Mario RPG introduced a timing component to enhance the power of your characters’ attacks and defensive abilities: press A at just the right time, and Mario will continue to jump on an opponent’s head, or throw more fireballs, or deliver a more powerful swing of his hammer. In Paper Mario, the timing — which was an excellent addition to the RPG battle system canon — is back, but also more diverse: now you time a hammer swing just right by holding back on the analog stick for the most damage possible, but holding too long results in the opposite of your intended effect. Maybe you have to watch a reticule moving around on screen to time and make more accurate the throw of an object one of your characters uses to attack. Or maybe you’re smashing a button repeatedly as fast as possible to fill a meter before the attack is finally delivered, in order to enhance the damage or area of effect.

From reading all of this, it probably sounds like I enjoy Paper Mario significantly more than Super Mario RPG, so what are they doing next to each other in these rankings? The truth is that while I appreciate the world and mechanics of Paper Mario more than the game that preceded it, Paper Mario has the same disease as literally every other Paper Mario title, in that it goes on longer than it should. I am desperate to finish every Paper Mario game by the time the end is nearing, no matter how much I’ve enjoyed myself to that point: there’s a real pacing issue they’ve never quite solved. Mario RPG, on the other hand, is an extremely tight experience, one you can wrap in around a dozen hours if you know what you’re doing. Paper Mario is about twice as long, which isn’t absurd by any means, but just like with sporting events, pacing matters a lot. And Paper Mario’s pacing is inferior to Mario RPG’s.

Another way of putting this is that the frequency at which I’ll revisit Super Mario RPG is a lot higher than that of Paper Mario. I do think Paper Mario is the better game, by a sliver, but there are only so many hours in a day, you know?

There are better Nintendo RPGs than these two, sure, but both Paper Mario and Super Paper Mario are deserving of inclusion on this list. The care for the source material is evident, as is the desire to make something new and different and worthwhile that can exist outside of just being another game with Mario’s name attached. These two games are inextricably linked, yet are their own independent creations, too, and you’re missing out if you haven’t played either or haven’t revisited in some time.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.