Ranking the top 101 Nintendo games: No. 9, Xenoblade Chronicles

Nearly the best game Nintendo never bothered to release outside of Japan, but as befits Xenoblade's story, that fate was changed.

I’m ranking the top 101 Nintendo developed/published games of all-time, and you can read about the thought process behind game eligibility and list construction here. You can keep up with the rankings so far through this link.

Xenoblade Chronicles isn’t just one of the best games in Nintendo’s history, but it’s also a significant turning point for them, as well as the game’s developer, Monolith Soft. Xenoblade Chronicles itself might be the best of the three games released in the series so far, but neither of Xenoblade Chronicles 2 nor the online JRPG, Xenoblade Chronicles X, are slouches, either: all three games made it into this top 101 project, which is a helluva batting average.

The original Xenoblade Chronicles sold just under 1 million copies on the Wii, despite being a late-life Gamestop exclusive in the North American market: XC released in April of 2012, about half-a-year before the Wii U hit shelves, and about half-a-year- after the release of The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword, which was considered to be a swan song for the little white console. Nintendo was impressed enough with the sales under these conditions that it re-released a New Nintendo 3DS port of Xenoblade Chronicles three years later, giving the game a version that was uglier, sure, but now portable: with the structure of Xenoblade being what it is, that was a welcome addition.

And now, Xenoblade Chronicles has gone from a game Nintendo wasn’t even going to bother to release outside of Japan to one that got a definitive edition on the Switch in May of 2020: that’s now the best-selling version of the game, outpacing the two previous iterations on its own, and the nearly three million sales it’s picked up over the years account for about half of what the series has managed since its inception.

The success of Xenoblade — and fans’ demand for it to be localized and released outside of Japan in the first place, which ended up organized under the “Operation Rainfall” banner — has seemingly forever turned the tide on Nintendo of America deciding to skip localizing certain major Japanese titles. There was never a question about whether either of XC’s sequels would come to North America like there was for the original, and there hasn’t been any kind of concentrated moment of localization frustration with Nintendo like there was back when XC’s release was up for debate.

[A brief aside: I’ve embedded the entire soundtrack above, and suggest you listen to it while you read the rest of this. More on that later.]

That Operation Rainfall I mentioned, if you’re not familiar, was a fan campaign centered around three different games that weren’t planned to be released in North America, even after they received English localizations for PAL regions. The Last Story, which if you can’t tell by the extremely on-the-nose name, was a Wii exclusive made by Final Fantasy’s creator, Hironobu Sakaguchi, and his development studio, Mistwalker. Pandora’s Tower, developed by Ganbarion, was an action RPG with a unique personal focus and story. And then there was Xenoblade Chronicles: while Nintendo simply published The Last Story and Pandora’s Tower in Japan, they owned Monolith Soft, the developer of XC, so deciding not to bring that to America was even more egregious before you even consider the quality of that game.

That’s not to take anything away from the other two titles, as both were in consideration for this list, but they’re more in the Baten Kaitos Origins “Just Missed” category of JRPG than they are at Xenoblade’s level. Xseed ended up handling publishing for both Last Story and Pandora’s Tower in North America, while Nintendo, eventually, caved and brought Xenoblade to North America themselves: if you think Xenoblade released late into the Wii’s lifespan, The Last Story didn’t hit shelves until August, just three months before the Wii U launched, and Pandora’s Tower actually came out the following April, a full year after XC.

Luckily, there hasn’t been a situation like this since. Nintendo even had Pandora’s Tower release on the Wii U’s Virtual Console shop for $20 to help compensate for how difficult it was to find a physical copy of a niche action RPG that came out after its home system was effectively retired: there are very few non-Nintendo-published Wii games games on the Wii U eShop, and even fewer of those on the North American eShop, but this time, Nintendo didn’t let Pandora’s Tower slip through the cracks like they did with its initial release. Progress! Now release Monolith’s Soma Bringer in English and we’ll forget there was ever a problem to begin with.

As for how Xenoblade became a turning point for developer Monolith Soft, well, outside of the obvious thing where they successfully created their most popular series, there is how both industry and fan attitudes towards them completely changed. I at some point have to talk about the actual game itself, so I’ll spare you from going through their entire history, but as Kotaku wrote about last fall, Xenoblade Chronicles was the first time that Monolith managed to release a game where the quality of the final product matched its big, bold ideas, where execution and inspiration were in harmony. It was not, by any stretch of the imagination, the developer’s first good game: the Xenosaga games deserve much of the criticism they’ve received, but they’re still a good trilogy of games, and both Baten Kaitos titles are great. But XC was Monolith’s first essential release, and they got there with help from Nintendo that they never got from their previous boss, Namco, nor from the Square executives whose lack of support caused much of the Xenogears team to split and form Monolith to begin with.

The focus Nintendo helped to give their new subsidiary — focus that, per Kotaku’s investigation, Namco never bothered to instill in Monolith or utilize themselves while overseeing their projects — helped make for both better game development and a better game. The three Xenoblade games are the best of what Monolith has managed to create this point, and the original, Xenoblade Chronicles, is the best of that bunch. Monolith has gone from a developer that Nintendo took a chance on because of their ideas and relationships that developed between the two during previous collaborations to one that is a significant part of the reason that Breath of the Wild is the way it is, with a world that works the way it does: who else was Nintendo going to entrust with designing massive, layered, highly explorable and compelling open-world landscapes to, if not the developers of Xenoblade? They’re arguably better at it than anyone out there these days.

Xenoblade Chronicles isn’t just one of the best Nintendo games ever: it’s the best JRPG of its generation, and its legacy as important to that genre as it is to Nintendo and Monolith itself. As Ishaan Sahdev wrote for Kotaku in that history of Monolith:

Xenoblade Chronicles won praise for its unique premise, incredibly well-crafted world map, excellent English dub, and most of all the sense of openness and freedom it offered the player—something Square Enix’s Final Fantasy XIII, which was meant to be the defining JRPG of the generation, had utterly botched. Where Final Fantasy XIII had failed, Xenoblade helped spark the JRPG comeback that would carry over into the next console generation, pulling Japanese games off of the sidelines and back into the limelight. To gamers, it was a reason to care about Japan again. To JRPG fans, it was a sign of hope—vindication of their favorite genre, following years of apathy from the industry at large. To video game critics, it was a change in the ongoing narrative about how Japan was becoming irrelevant. And finally, to fans that had once mocked the idea of Nintendo acquiring Monolith Soft, it was an eye-opener.

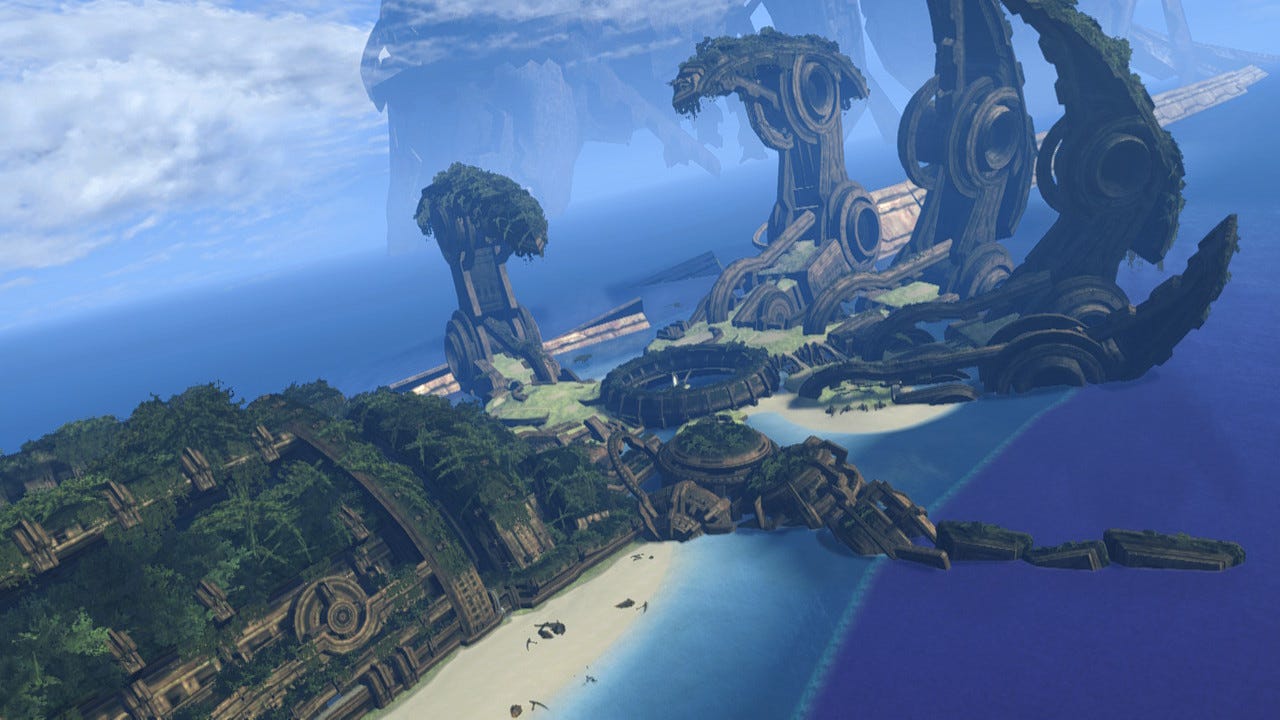

Alright, so we’ve established that Xenoblade Chronicles is important, but now let’s talk about the game itself. The game is set on an ocean world where two massive gods were in combat with each other until they were both injured to the point that they stopped in their tracks. One, the Bionis, was more in tune with nature, and multiple races of people were born there, as well as plants, monsters, and animal life. The other god, Mechonis, is full of giant mechs, robotic life: the kind of folks you think would live on a place with “Mech” right there in the name. You spend the game climbing up the Bionis and making your way to Mechonis, back-and-forth as necessary, a massive open-world taking place entirely on the bodies of gods so huge in scope that multiple civilizations sprang up on them, so huge that different areas of these gods’ bodies have different weather patterns. The valley that also serves as a land bridge between the two gods is actually just the sword of one of them, which had been swung into the body of that god’s opponent millenia before.

This isn’t just some cool effect designed to give the game a weird premise: the bodies of these gods play a significant role in the story, and they have meaning well beyond “hey wouldn’t it be cool if?” that helps make Xenoblade’s story as engaging and as memorable as it is. These civilizations that sprung up on the gods, what is their purpose? What does it mean to defy fate, to change the future, to fight for what you believe in? Does the land these people live on belong to them and to the rest of the life living on them, or does it belong to the gods themselves, who [s-p-o-i-l-e-r-s — there are going to be a lot of these in the description of this story-driven, 10-year-old game] it turns out might not be quite as out of commission as they appear.

Monolith asks a whole bunch of big-picture questions like this in Xenoblade, but they actually stick the landing while answering them, unlike in Xenosaga, where the fascinating philosophy builds up so much that, regrettably, does not always end up in as intriguing a spot as the questions themselves. The gameplay is also light years beyond what Xenosaga managed: Xenoblade isn’t turn-based, but it isn’t exclusively an action RPG, either. It blends multiple styles together into a battle system that is very much, well, Xenoblade.

You can control one of three party members at a time — you’re rarely forced into selecting which of the game’s seven playable characters you’re using in battle — while fighting enemies. There is some crossover of skills, with different characters maybe excelling a little more at one aspect than another, while also having strengths found elsewhere, so you can play around with the bunch of them until you find the party that works best for you in general. Or, you can spend time figuring out situational parties for different enemy types, if that’s your thing. Either way works, the choice is up to you, etc. The extensive customization of skills, and that there are more equippable skills than their are active skill slots, helps you further tailor the way a given character plays, too.

Explaining exactly how Xenoblade’s combat works is a thing we do not have time for: it takes the game dozens of hours to fully take the training wheels off, but its to the credit of the game designers that it never feels like you’re being held back before that point. There is so much to absorb and learn through repetition and experimentation that your hands are full, and the game does a better job of pacing it all out than its contemporary, Final Fantasy XIII, while also providing a far more intriguing and enjoyable… well, everything, than Final Fantasy XII, whose battle system Xenoblade drew some comps to. I think that’s kind of a simplification of things, though, the kind of comparison you get when there just isn’t much to compare something to because we’re in mostly uncharted territory. Xenoblade’s blending of real-time battle with turn-based battles feels more like, well, Xenoblade than anything, and they’ve continued to iterate on it for not just the original’s sequels, but also for each of the expansions, for lack of a better word, developed for XC and XC2.

Mostly what you need to know about the battle system is that you have a basic attack that characters will automatically perform unless you tell them to use a skill or attack that will need a cooldown period before it’s used again. A gauge fills as you deliver damage, and when one segment is filled, it can be used to revive a fallen party member. You want to fill that gauge all the way up, though, because it’s also how you power your coordinated party attacks that melt health off of enemies: it’s absolutely vital to use these party attacks against bosses, since it interrupts their own attacks and, if executed expertly by you, can keep going for a while, amassing significant damage you otherwise couldn’t easily inflict. If you don’t have a full segment, and your controlled character falls, you’ve lost. You retain all experience, though, and go back to the last checkpoint on the map you passed by, so you won’t lose progress when this happens.

It’s a fulfilling, engaging battle system, one where you need to be aware of where you are in relation to an enemy, in order to best use the skills you have: some do increased damage when striking from behind, some can cut into an enemy’s defense and allow for your party to inflict increased damage for a short time, but only if you attack the enemy from the side with it. You need to be on the move, if you are not playing as a tank, you need to ensure that you are not drawing too much aggro in order to best position yourself to utilize these location-based skills… you don’t just sit there waiting for auto attacks to do the work for you. The only real reason to utilize auto attacks at all is that they can fill up the gauge that allows you to utilize each character’s special skills. For Shulk, that means the ones that let him use the Monado to make mechs from Mechonis susceptible to regular weapon damage, or to utilize the functions of the sword that let him see — and change — the future.

Shulk has visions, thanks to the Monado. Sometimes, they’re in the story, and inform where it and your party are going. More often, they’re in battle: Shulk senses that an enemy is about to use an attack that will down a comrade, and a clock starts ticking. If Shulk can use the appropriate skill (or if your lead party member can notify Shulk via button press that this is necessary) in time, be it a defensive shield or an ability to dodge attacks or a number of other selections, then the future has been changed, a dire fate avoided. It’s an excellent mechanic for battles that adds yet another wrinkle to an already layered and engaging process, and it’s also a significant part of the game’s themes and story, as well. Xenoblade is all about changing the future, of denying fate, of telling gods exactly where they can shove their mandates. Xenoblade might be my favorite JRPG from the “find and kill god” genre, which is saying something, but a lot of that has to do with the characters, their struggles, their interpersonal relationships, and their joint agreement that their god kind of sucks and needs to be taken down a peg or two.

Those seven characters are part of the reason the story works so well and feels so engaging. Shulk is the primary protagonist and wielder of the Monado, a sword of unexplained origin and power that allows him to see visions of the future. Reyn is his lifelong friend, a muscled companion who serves well as a tank. Fiora is their hometown friend, who you use early on before tragedy strikes and separates her from your party in what at first seems like the fridging of a love interest, but don’t worry, she’ll be back, and significantly powered up. Dunban is her brother, a legendary swordsman and the previous wielder of the Monado, until its power permanently injured his somehow-unworthy sword arm. Sharla is a woman from another homs (the game’s word for human) colony whose partner was taken by the mechs from Mechonis: she serves as the game’s equivalent of a medic, except she heals you the same way she damages enemies: with a sniper rifle. Riki is a Nopon, a race of creatures that has appeared in each Xenoblade game to date. They’re small, cute, and pack a surprising, well-balanced punch: you might recognize him as an assist trophy in Smash Bros., if not from XC. Then, finally, there is Melia, XC’s equivalent of a mage, and a character who has nothing good happen to her, ever. At least, not until Monolith’s epilogue for the Definitive Edition of the game, which even they admitted was something of an apology for the one character whose life was turned upside down far more than any other protagonists’.

Enemies are on the map, and almost entirely avoidable since you always have the option of physically running away from a conflict. Sometimes, you do this because you don’t feel like battling right then, and sometimes, you do it because you’re level 20 and a level 75 creature just decided you look delicious. Xenoblade is not bringing you along a road with progressively more difficult enemies, where you always have foes you’re capable of handling in your path. No, Xenoblade is much more honest about what life on the massive plains of a world full of monsters would be like. You’ve got your predators, and you’ve got your prey, and which you are depends entirely on what monster it is you’ve got in front of you… or chasing you. Enemies won’t bother you anymore if you’re out of their league, and sometimes, tougher enemies will ignore you for being too small-time for them. Experience scales based on your level vs. an enemy’s level, too, so you never feel compelled to stick around fighting weak, and therefore boring to battle, monsters. You’re always seeking out newer, tougher challenges as you grow, and those, in turn, give you the most experience points to further grow your strength.

If you ever find yourself falling behind in levels, you can grind a bit on enemies you know you can handle that are still of a higher level than you, and you’ll quickly catch up. However, if you just do some sidequests, you’re unlikely to fall behind. Sidequests in Xenoblade Chronicles are a bit divisive, but part of the problem is that they’re treated as optional, or something to be done when you aren’t progressing through the main story. They’re optional, sure, but the options are “do more sidequests” or “fight more battles.” If you want to fight more, it’ll take you longer, as sidequests are often just something you can do without even making much of an effort to do so. Whatever items you need to collect or creatures you need to defeat to complete them are often found on the path you were already taking, anyway, so, agree to do every sidequest you find, and then you’ll complete most of them without going out of your way to do so. A whole bunch of sidequests are turned in without you even going back to the character or whatever that assigned them in the first place! And since fast-travel is accessible essentially immediately, and there is no shortage of fast-travel points, even turning in quests isn’t a big deal or something that puts you out.

Sidequests are such a great source of experience, actually, that Xenoblade lets you shut off gaining XP from anything besides battles, so as not to disrupt the game’s balance if you decide to do most of them. Throw in that there is this mode as well as an easy mode that makes it a lot easier to tackle any boss or high-powered unique enemy if you happen to be underleveled — or just want to enjoy the riveting story, world, and characters without making difficult battles a priority — and Xenoblade can avoid ever feeling like a chore. You’re looking at a game that can take 70 hours if you aren’t taking your time, less than that if you play on easy and require less XP and leveling to get by, and twice that if you want to do everything, like completely rebuild and repopulate Colony 9, which in turn makes your party stronger and better equipped. The pacing, though, is excellent, especially if you remember my advice and don’t make sidequests a secondary thing: do them along with the main quest, and everything will flow so much more smoothly.

Graphically, the original release of Xenoblade wasn’t special. The character models were well-designed, but a bit on the ugly side, especially since it was a late-life Wii game even before it got its even later North American release. The landscapes, though, were stunning, even without the benefit of HD, simply because of how they were designed and rendered. Just a beautiful game with an obvious desire to wow you with its design decisions and its world, just as much as its world building. Finally getting to see if all in HD on the Definitive Edition was a treat, even in this age where 1080p is years behind the non-Switch curve.

Monolith didn’t just put the original version of the game into HD. They completely redrew the characters, in a different style, that is more in line with where they ended up stylistically for Xenoblade Chronicles 2. The side-by-side comparison shots for the character art, that’s where the most significant change in appearances is. I mean, look at these:

It’s not just higher resolution, but better facial animations, lip syncing, and more appropriate visual responses to the dialogue and scenarios, which helps with the whole connecting with these characters from an emotional standpoint thing. The game was certainly fine as is, but these kinds of touches of modernization mostly helped bring a game that was ahead of its time enough in every other way to a point where it all felt more of a piece, like a game of this size and scope finally released on hardware that could fully support its vision. So, welcome changes and tweaks, and not a drastic departure from the core gameplay of the original or anything like that. That part of the experience is the same.

It also helps that the character design finally got the horsepower behind it to have it stand alongside the creature, mech, and landscape design, the brilliance of which was evident even on the low-powered Wii and the lower-resolution New 3DS. If you're familiar at all with the work of Monolith, you know they know how to draw a monster, or a mech, or some massive living creature used for a task you wouldn’t normally consider a massive living creature to be used for. They love color, they love style, and they love hiding away some of that beauty in Xenoblade’s day/night cycle. Satorl Marsh is a grey and brown wasteland during the day — an ugly, dangerous marsh, but at night, well:

Still dangerous, even more so, really. But look how pretty! Really, the video doesn’t do it justice, but it’s hard to find a better one that shows what I want it to, so you’ll just have to play yourself I guess.

The sound, too, is stellar: there is a reason I suggested you listen to this soundtrack while you read. The main theme and title screen music for Xenoblade is beautiful, a piano-led ballad that successfully emotes even before you can attach any characters or story beats to its sound. Then there’s the Gaur Plain theme, from the game’s largest, most open part of the open-world experience: you’ll become familiar with this theme in a hurry, but that’s a positive.

It stirs a sense of adventure in you, appropriate given how simply entering the expansive plains make you feel. The various battle themes are all standouts, as well, and music can change mid-battle depending on whether you have the advantage or disadvantage. There is an ebb and flow to battle, both in how it feels and how it sounds, and it’s part of the complete package that makes Xenoblade just flat-out work.

The music, throughout the game, always feels perfect for the moment and environment that it’s in. It’s one of the best JRPG soundtracks going, one I would listen to outside of playing the game, even before the updated, and superior, Definitive Edition versions of the tracks released. If you prefer the originals, though, the Definitive Edition of XC includes those as an option for you instead, but the updated ones sound richer and fuller to me.

Listen, I bought Xenoblade Chronicles from Gamestop when it first released, and it did not disappoint. I purchased the New Nintendo 3DS edition when that released, too, and it going portable, with the dual screens de-cluttering the HUD, made it worth buying again. While the Switch’s Definitive Edition loses the dual screen nature and adds in some of the clutter once more, everything else about it is an improvement on the previous iterations. It’s a game so, so good, so worth revisiting, that I had no qualms about buying it at retail price on three occasions over the course of less than a decade. And I say this as someone who sometimes buys the original, much cheaper releases of PS3 or Xbox 360 games after they get a full-price, PS4 or Xbox One remaster, because I don’t see the point in paying for a little graphical fidelity upgrade.

The Definitive Edition of Xenoblade isn’t just named that for marketing purposes, but it actually is. It remains portable in its Switch form, which is perfect for a game of its length that you can also chip away at one quest at a time, when you’ve got the time. It’s at its best in both the audio and visual departments, it has more game to it thanks to the (enjoyable) Melia-focused epilogue, and all of the quality-of-life improvements help make it the most accessible version of the game, too. Even if you weren’t in love with Xenoblade Chronicles 2, which was a Switch original unlike its predecessor, this first game is worth trying out. The whole world, from a thematic point of view to the actual, physical world itself, to the characters and their relationships with each other and the world around them, is worth experiencing. That all of it is contained within a game that also has a stunning soundtrack and best-in-class battle system is a significant bonus, and it all worked together to create one of the best JRPGs, and best Nintendo games, going.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.