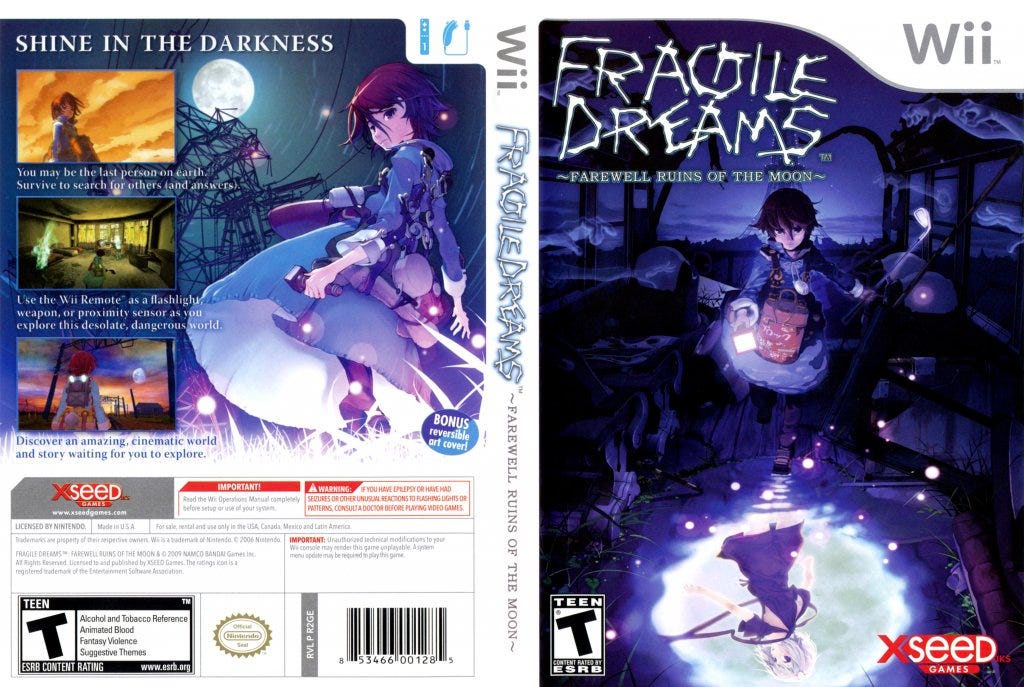

Re-release this: Fragile Dreams: Farewell Ruins of the Moon

Fragile Dreams isn't the best game you'll ever play, but it's one worth experiencing for what it does well.

This column is “Re-release this,” which will focus on games that aren’t easily available, or even available at all, but should be once again. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Fragile Dreams: Farewell Ruins of the Moon probably released at the wrong time. I don’t mean the wrong time of year, though, sure, releasing in March 2010, days after the highly anticipated high-definition debut of the Final Fantasy series, Street Fighter IV, God of War III, and on the same day as the expansion to Dragon Age: Origins probably wasn’t any help to the marketing of a brand new intellectual property that XSeed had to rescue from Namco for it to even get a North American release. And even your more niche gamers who would be paying attention to the release schedule of a publisher like XSeed were focused on things like Shin Megami Tensei: Strange Journey, or Infinite Space, or… OK well maybe I do mean the wrong time of year, too.

The point I was trying to make before I derailed myself is that Fragile Dreams tried to do something that 2010 maybe wasn’t ready for in the way 2021 is. It is a game trying to share a feeling more than it is anything else. There is some action, sure, and a little exploration to be done, but it is mostly about that one feeling, and how all consuming it can be. Fragile Dreams is a game about loneliness, and trying to confront that loneliness, and those feelings permeate almost every facet of it.

It’s probably the kind of game, warts and all, that would get more attention and notoriety in the present day given how game criticism has advanced to better handle titles that are more hyperfocused on a particular vibe or theme than they were successful at being perfectly mechanically sound critical darlings. I don’t like using Metacritic as a judge of much at all, for a number of reasons, but I do think it’s worth pointing out here that Fragile Dreams scored a 67 out of 100 based on 41 reviews, giving it a “mixed or average” reception. I don’t think that’s off by much, either. Fragile Dreams certainly has its issues, having to do with tedium or just some strange (lack of) quality of life decisions that were hard to ignore in 2010 and are even more difficult to ignore now. But what it does well — crafting a sense of loneliness that reflects the game world and the state of mind of the protagonist, Seto — worked in 2010, and probably works even better now, considering the trajectory of the reality we live in.

And that sort of thing is why I don’t like just leaning on a game’s score or Metacritic average to determine how worthy of your time it is: Fragile Dreams has plenty to say and to make you feel, and deserves another chance to get you to listen.

Stephanie Sterling reviewed the game for Destructoid back when it released, and this paragraph gets at the heart of things:

And yet … I love this game. I love this insulting, infuriating waste of time. I will never, ever play Fragile Dreams again. However, I am intensely glad that I have played it once. For everything this game does wrong, and it does nearly everything wrong, it manages to make up for it with a sublime story, amazing characters and some of the most memorable scenes I have ever had the pleasure to witness. At times I truly did want to throw my controller and turn the Wii off. Yet I couldn’t. I couldn’t tear myself away because I was so hooked by this game’s stellar narrative and the beautifully bleak and melancholic atmosphere of the whole experience.

I do think there are reasonable excuses for some of the issues, such as with combat: Seto is just some regular kid, alone in the world, not trained for battle or anything like that. He begins the game with a small tree branch that he defends himself with, and picks up butterfly nets, brooms, and other just-laying-around objects that could be used for melee purposes in a pinch. He can’t dodge or roll out of the way or whatever, but as Nintendo Life pointed out back in 2010, he’s not The Legend of Zelda’s Link. He’s Seto: a timid, sheltered young boy just trying to survive until the next day in a world that, as far as he can tell, might not have any other survivors in it. Sometimes a feral dog comes at you, and it takes all you’ve got to smack it down with a broom before you’re turned into a meal. It doesn’t need to be pretty, and doesn’t really make much sense for it to be pretty, either, considering. And, it’s a Wii game where you just press or hold a single button for combat, instead of waggling: the Wii remote uses the IR sensor to control where your flashlight is pointing, instead, and that was the superior design choice to make.

Weapon durability, too, is an overstated issue, especially since it fits thematically with a game world where everything that used to be whole is broken or breaking, but I also understand that kind of thing is a third rail with some people. But you won’t hear me argue in defense of the inventory restrictions or the constant need to stop at campfires in order to shift items from your hands to your suitcase and make room for new items, or the backtracking, and so on. I will, like Sterling, just say that the game is worth experiencing in spite of all of those kinds of decisions that make it seem as if developer Tri-Crescendo didn’t actually want you to play the game.

And it’s because of how hauntingly beautiful it is, how effectively it makes you feel Seto’s loneliness and isolation, how it manages to make you care about the other characters Seto does manage to discover in his travels, before he parts with them for one reason or another — sometimes because their paths have crossed but now must diverge, and sometimes because death is a natural part of any world, but especially this one.

It is either the perfect game to play in this historical moment, or, the one you most want to avoid. Present-day Destructoid’s CJ Andriessen revisited it closer to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, well before vaccines ended some of the total isolation everyone was feeling, and found it even more affecting than it initially was:

Playing Fragile Dreams in the era of COVID has given me a new appreciation of what Namco and Tri-Crescendo managed to pull off more than 10 years ago. Admittedly, many of its aspects have aged horribly or weren’t even that good to begin with. But it’s a wistful experience, one soaked in solitude and heartbreak, driven only by the hope there is something better on the horizon. That’s what the tower was to Seto, a chance at a better life. There was no guarantee it was waiting for him once he arrived. If you’ve beaten Fragile Dreams, you know exactly what is and isn’t there. But in the hours leading up to that arrival, it’s the hope there is something beyond the bleak existence he knows that pushes each foot forward.

Emily Hobbs, before the pandemic began while writing for DualShockers, described Fragile Dreams as “an exercise in poignancy,” focusing on the “remarkable storytelling of an unremarkable game.” Hobbs felt that, even if Fragile Dreams wasn’t a game to necessarily be recommended as a must-play, that it was the kind that was so effective in achieving its thematic goals and in telling a story that other developers should learn from it. And I have to agree, at least on the being able to learn from it part: Fragile Dreams had a specific goal in mind, thematically, and regardless of what you think of the rest of its systems, it achieved that goal.

I do think it’s worth playing, though. Maybe it needs a few tweaks here and there to fix some of those quality of life issues I referenced earlier, but if Fragile Dreams got an HD upscale and digital re-release at a budget price, it would be worth the 10-12 hours you put into it, even if some of those hours are tedious ones. It’s not like anything quite like it has released since, so if you want to experience what it has to offer, this is it.

Seto’s own brief relationships with various characters in the game are certainly a chance to feel and reflect on loneliness — the game opens with Seto, alone, moments after burying the man who he called grandfather — a man who never actually told Seto his name, despite the fact they lived together for some time. Seto finds his flashlight, and a letter with the old man’s last wishes — that Seto set out for Tokyo Tower, which is illuminated in the distance — and the game begins. Shortly after leaving the observatory where he lived with the now deceased elderly man, Seto hears a young girl singing. She falls down from where she is perched upon seeing another living person, and Seto goes to check on her, briefly touching her cheek: neither of them seems to know how to react to that having happened, as neither of them is used to the touch of another person.

Seto now is intent on not just getting to Tokyo Tower in the hopes of finding other survivors of an unexplained apocalyptic event that left Japan and the world in ruins, but also of finding this unnamed young girl who appeared to be around his age, too. Tokyo Tower is a place Seto hopes has other survivors, but this girl is more than just hope: she is real, and he knows, because he was able to touch her. Considering that numbering among the companions he briefly interacts with in Fragile Dreams are a talking backpack that serves as an encyclopedia and conversation partner, a robot, and a ghost, that brief touch with another living human stands out to Seto.

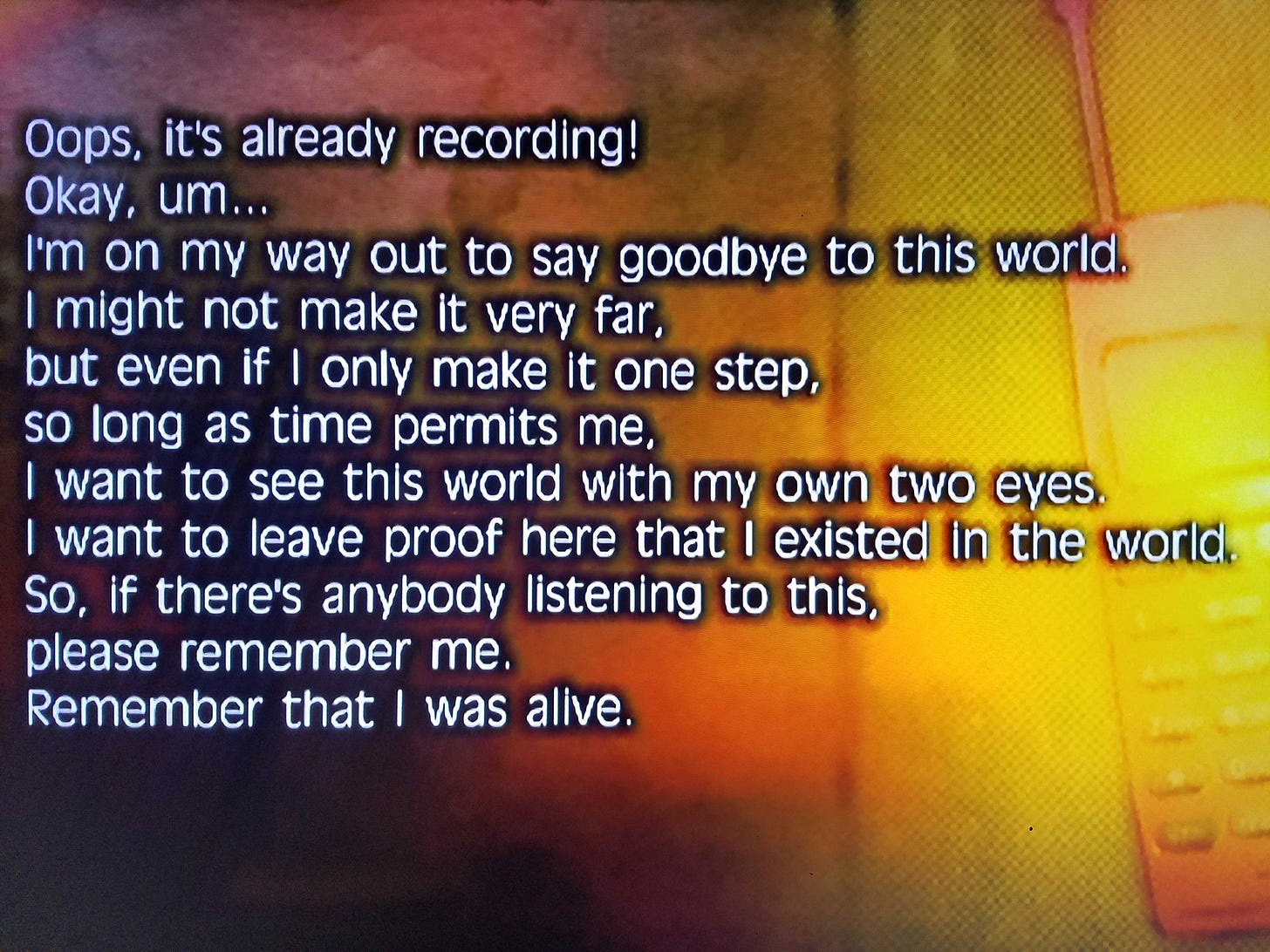

Most of the interactions and conversations within the game are actually with people who are no longer there. Seto finds various objects throughout the world — a shoe, a class photo, a dog collar — that he can examine when he’s at a campfire to rest and save. Whenever one of these objects is found, a short, voiced cutscene plays, with art of the object in the background and text being spoken in the foreground. Each one is the story of a person (or dog!) all too aware of their own loneliness and isolation, of a world that was changing for the worse, of the inevitability of their own death. Many of them were going to sleep for the last time, whether they knew it or not, and that feeling something is off, that the world isn’t right, is reflected in these scenes. The world of Fragile Dreams might look empty, but its ghosts, and their memories, live on to be discovered.

There are a few ghosts who you can send off into the oblivion they crave, freeing them from this dead world, by fulfilling the final wish that’s kept them here. A reunion with an object of affection once lost, spending time playing with a young, lost girl who was just waiting for her mother who never did come… by and large, though, the ghosts you meet are unreachable by you, their memories all that persist. Except for the ghosts you meet in combat, of course, the ones that appear like blue jellyfish and float through the air, who it turns out are simply manifestations of the thoughts of people who no longer live in the world. If Seto dies, you will see his own jellyfish spirit float up from his body, now trapped in the world as nothing more than a collection of regrets like the rest. Seeing that screen can certainly change how you feel about smacking those ghosts around for the sake of experience points.

The soundtrack, too, serves to emphasize the loneliness of Fragile Dream’s decaying world. Almost all of the game’s tracks are somber affairs, and many of them have just the one instrument: a piano. If you’re familiar with Breath of the Wild’s soundtrack, it utilizes some of the same musical tricks to invoke feelings of loneliness and melancholy. In some of those songs where there is nothing more than a piano at work, each note echoing the loneliness and sadness it is meant to convey throughout the game world.

Barely any of the game’s music feels like it’s in a hurry to get to its destination, either, which certainly fits the pacing of the game and the ennui inherent to this dying, lonely world. Even the music that plays when enemies are nearby is slow, moody, focused more on strengthening the haunting ambiance the game was already going for rather than inspiring any kind of haste or feelings of dread. Much of it isn’t necessarily building to anything, either: it is just there, the soundtrack to the loneliness you feel in the moment it is playing.

The piano work in this game is really just excellent, and basically unassailable, too: it is perfectly suited to the task it was given, and greatly enhances the experience of the game. Maybe more so than any other element within. As hauntingly beautiful as the landscapes and images of the moon and night sky can be, as affecting as hearing the story of a dog who is realizing his owner is setting him free the night before he goes to sleep to never wake up again is, the soundtrack is the most powerful tool in Fragile Dream’s loneliness toolbox, because it sustains and maintains the atmosphere in between all of those other moments.

Again, this game is certainly frustrating for reasons that have already been addressed. It should be a classic, but instead, has mostly fallen out of memory. Even just to get people to play it, were it to get a second chance, it would need a re-release and a marketing push that actually tries to describe what it is — a loneliness simulator — instead of an amalgam of genres (an action-adventure JRPG survival horror experience!) we were already aware of that don’t quite fit the something new that Fragile Dreams was going for.

And it would have to get a re-release so that anyone can actually find the thing to play it, too. Fragile Dreams was a commercial failure over a decade ago, and released as a Wii exclusive. Namco didn’t even bother to publish the game themselves outside of Japan, leaving the smaller outfit of XSeed to do it. There just aren’t that many copies out there, and the ones you do find are priced accordingly. If you’ve got $120 to $200, you can find a copy on Ebay. I get the sense I like Fragile Dreams more than most, and I waited until I could find a listing that just had the game and a generic Gamestop used game case, so that I could spend a far more reasonable amount of money on a copy. If I had a PC that could run Wii games on Dolphin, though, I wouldn’t even have gone that far. I don’t, though, so buying just the disc for around the original MSRP was considered the bargain version of getting this game.

Even with a re-release, Fragile Dreams wouldn’t be a breakout hit or anything. It is a game that succeeded at its goal of crafting a lonely world, though, and telling a story about that world and what little remained within it. And that makes it worth experiencing. If you have to emulate it, do it, because as frustrating as the game can be, as much as I had to work my way through bit by bit in between other games, it was worth it to experience the parts of Fragile Dreams that work exceptionally well.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.

I loved this game so much

My favorite one at wii