Re-release this: Tetrisphere

A Tetris variant you won't find in Tetris Forever, despite Tetris' creator himself working on it.

This column is “Re-release this,” which will focus on games that aren’t easily available, or even available at all, but should be once again. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Digital Eclipse’s most recent Gold Master series release is Tetris Forever, which aims to tell the history of the origins of Tetris, yes, but mostly through the lens of rightsholder and regular developer and publisher of those games in its early years, Bullet-Proof Software. There’s nothing wrong with that approach, as it set out for a specific task and seemingly accomplished it, but if you were waiting for a broader look at Tetris’ history, with some of its even stranger one-offs or development situations in there outside the realm of BPS’ own efforts, that’s not going to be the place for it. Unless there are some major downloadable content packages coming down the line that specifically highlight the contributions and innovations of Nintendo, Sega, and Arika, and so on for the franchise, anyway.

Which means we’ve still got to yell about the many Tetris titles out there that remain unavailable in the present, such as Nintendo and H2O Entertainment’s wild, three-dimensional take on the legend: Tetrisphere. Tetrisphere is one of those titles that makes it clear that Tetris Forever was structured how it is due to rights issues, and not because its developer somehow forgot or didn’t care about a particular game. Alexey Pajitnov himself, the creator of Tetris, worked on Tetrisphere, and this despite being employed by Microsoft at the time! But it’s a Nintendo-published game, with the “Tetris” name licensed to them for this 1997 release by way of The Tetris Company, which formed in 1996 in another partnership between Pajitnov and Bullet-Proof Software’s Henk Rogers, as a way to manage Tetris’ rights and licensing globally. So, it’s one that requires Nintendo’s approval to resurface. Which they could do, at minimum, on the Nintendo 64 portion of Nintendo Switch Online, though, Tetrisphere certainly has enough going on that it could stand an HD re-release in the present. Said re-release didn’t come via Tetris Forever. At least, not yet. (What? I don’t want to give up hope about future DLC that makes truly Tetris Forever definitive.)

At first blush, Tetrisphere has little Tetris in it, outside of the use of familiar shapes. After all, the playing area is a rotating sphere, and the shapes, familiar as they might be, are all 3D. Despite the look and very different way of thinking to succeed at Tetrisphere, though, at its core, it’s still a puzzle game where you must match pieces where they fit, must clear as many as possible with proper placement and planning — you must spend your time building something in order to dismantle it, same as any 2D, falling-block Tetris variant. What’s a bit different about Tetrisphere, however, is that the playing area is the blocks themselves, right from the start, and rather than perpetually clearing lines, you’re attempting to get into the core of the sphere. Narratively, it’s to free a little robot pal from within the insides of the sphere, but it’s really just the game’s way of showing you that you struck where there no longer is a sphere to clear. You hit the bottom, as it were, and there’s nowhere left to dig.

Playing Tetrisphere feels like peeling a hardboiled egg, and without the mess. Sometimes you’ll get some huge chunks of the outside covering off all at once, maybe even unexpectedly, and other times you’ll just be picking away at little bits here and there. You just keep working at it until you get to what’s inside, and then it’s on to the next egg/puzzle. It’s got the satisfying feel a puzzle game needs for you to keep on plugging away at it, and while it starts out fairly easy, in the sense you don’t need to master its system in order to progress, the difficulty comes with time. The second half of the game, which doesn’t even unlock until you complete the first half and see credits roll, makes this truth apparent in a hurry.

Tetrisphere wasn’t originally a Nintendo 64 game, nor a Tetris variant. Developers H2O Entertainment were making a game known as “Phear” for the Atari Jaguar, and was showcased at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in 1995, at Atari’s booth. Video of that demo is available, and looks pretty different from what the game ended up becoming, which isn’t surprising given the N64’s horsepower. Per the September 1997 issue of Electronic Gaming Monthly, Nintendo saw the game at that same CES and acquired the rights to it as an N64 exclusive shortly after.

It would take until August of ‘97 for Tetrisphere to release, and it had gone through quite the overhaul in that time. The game demo showcased at WCES in 1995 was but a single mode in the finished product. As an IGN story detailed, the game’s engine had been enhanced in a way that allowed a smaller portion of the sphere to be visible at a time in comparison to the original setup where the whole sphere was seen, which enabled a smoother experience on the frame rate side, as well as a two-player mode. These changes were welcome ones: the two-player mode needs no explanation, but giving how desperate things can get in Tetrisphere when the end is closing in on you, how quickly you need to be able to spin that sphere around in order to get to a space where you can successfully drop a piece, a smoother and higher frame rate is certainly appreciated, and helps the game feel as good as it does to play.

You don’t create lines in Tetrisphere in order to clear pieces. Instead, you need three like pieces to be touching each other in a row, in some fashion or another. They can be stacked, they can be next to each other, however you can make it work. You might not even see all of the pieces, as some are under others or tucked away to the side in a way that’s obscured at the moment you go to drop a piece, but luckily, the game lets you know when a match can be made. Where you next piece you’ll drop is lights up with a white outline when this happens: if you drop a piece in a place where there is no such outline, you’ll be punished for it, which you can only do twice and still complete the level. A third misfire, and you fail.

There might already be a bunch of the same pieces touching, but if they were there as part of the playing area when the level started, they don’t simply match up on their own: they need to be activated by your own block drops. Say, if you’ve got eight of the T pieces all lined up across the sphere, with a break between those and another pair of them to their left, you can slot in one more T piece in that spot, bringing them all together into one huge clear of that particular kind of piece. Other pieces might drop from where they were because of this, causing further matches, or you could just open up some clear spots for focusing future pieces in by doing so. That kind of digging is the key to Tetrisphere: you aren’t trying to match all the pieces in the playing area, but instead, you want to make your way through the sphere. Constantly shifting around can score you more points, but focusing your efforts into one general area will pay off in successful clears. And it’s a real race against the clock situation as the levels get tougher.

The spheres are larger, meaning you have to peel off more layers before you can get to the center. Larger spheres also means less time for you to succeed: Tetrisphere has a timer, and that timer is the proximity of the sphere to you, the player. The closer it is, the closer you are to being penalized, and the more difficult it is to see more of the sphere at once. There are different colored clocks that represent how close to being penalized you are, but you don’t necessarily need those, since you’ll feel how close you are to getting in trouble, anyway: no time to look at your watch, the sphere has lost any semblance of caring about your personal space, time to find a bunch of quick matches to slow this down.

Whenever you clear 19 or fewer pieces at a time — which is pretty regularly — you’ll see sparks fly down and touch pieces. The pieces that are hit by these sparks become Power Pieces, and, when cleared, they give you some extra seconds on that incessant timer that’s threatening to crush you via sphere. You can also move Power Pieces up a layer in the sphere, bringing them out from underneath a piece, which is huge for both making additional matches happen and for clearing multiple spots of sphere with a single piece’s movement. Power Piece chains also clear slower, which allows you more time to make your next play, which can keep a clear chain going.

There are Gravity Combos, which occur when a piece falls from a clear and kicks off another clear amid matching pieces. You can also manage this just by sliding a piece around — hold down the B button over a piece you want to move — and causing it to fall and match that way. Then there are Fuse Combos, where you grab a flashing piece about to cleared during a Power Piece clear, and drag it elsewhere for a different clear. These special kinds of clears can up your scoring multiplier, which, other than that they can clear out large chunks of the sphere all at once if you can pull them off, is the only other reason to bother to learn these tricks. They’re both good reasons, since survival — you know, not failing — is the best way to rack up a high score, anyway. And nothing will ensure your survival more in the tougher levels than being well-equipped to rip apart even the most difficult spheres as fast as possible through special combos.

You’ll find smaller square blocks around the sphere, which can be knocked aside while moving a larger piece with the B button — sometimes causing pieces to fall or clear as they’ve lost their connective point to the rest of the sphere — or become part of a larger combo. If you’ve got enough of them in one place, they might even convert into a larger piece, which can be cleared. Keep an eye out for these, as two piece that aren’t next to each other might be able to be made to be by clearing out these smaller blocks — do this, then place a third block on top, and you’ve got a clear going.

There is also “magic” in Tetrisphere, which is a funny name for a bunch of explosives and magnet guns, which you earn by clearing magic blocks, or a clear of 20 or more pieces — that 19 earlier wasn’t an arbitrary number. You activate magic with the C-down button, but it’s something of a last resort for clearing out a bunch of blocks at once. There are six levels of magic, and a variety of magical attacks that go with it: the Firecracker clears uncovered pieces where it’s fired, the Dynamite works similarly but split up over a larger area, the Magnet pulls pieces at your own direction, while the Ray Gun does that, but more so. The Atom is like the Firecracker and Dynamite but for the entire sphere, while the Bomb does this and then takes out some newly uncovered pieces where it lands, to boot.

You don’t want to depend on magic to save you, as whatever you’ve got stored away vanishes whenever you’re penalized, whether by placing a piece on your own where a clear won’t occur, or because the sphere slammed into the foreground because you took too long to solve the puzzle. But when you’ve got it, and you need it, it’s great to be able to deploy it, and it might just keep you from losing a life every now and again, too.

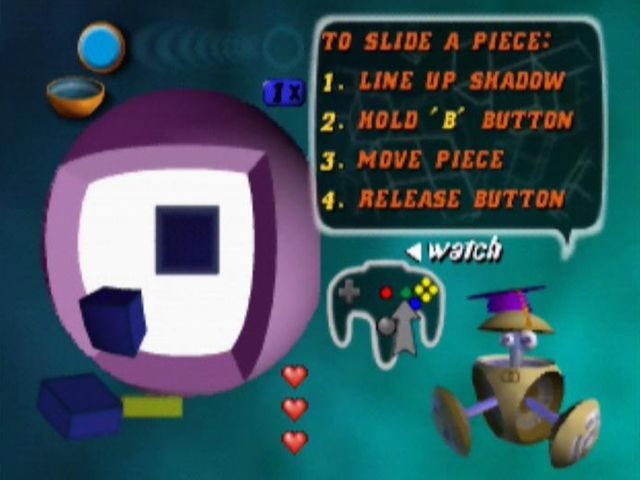

All of this is a lot to take in just by reading, but there’s some good news on that front. Tetrisphere has a tutorial mode within it, which helps lay some of the groundwork for you, and the rate at which difficulty increases is pretty slow. You can get a good grasp on the basics before the game needs more out of you than that, to the point that, when you first see the credits, you might be wondering if that was it. That’s just the first five episodes, however, with 10 stages within them a piece: there are another five episodes to follow, and those are for the people who want to complete Tetrisphere for real.

In addition to the multiplayer and practice modes of the game, there is Rescue, which has been explained here already — that’s when you are trying to get to the center of the sphere to free the little robot contained within it. The yolk to Tetrisphere’s egg. Hide and Seek has you attempting to complete challenges, such as clearing pieces from a specific part of the sphere, which might involve clearing other parts of the sphere to live long enough to manage that goal — the “Tower” challenges within Hide and Seek were what the original Atari Jaguar version of the game played like. Time Trial gives you five minutes to post a high score. Puzzle mode does away with the timers, and instead has you focus on clearing the entire sphere. Lines mode is a hidden one enabled by making your name “LINES”; in this mode, you can’t drop pieces, but instead have to clear the shapes every other possible way, i.e. through holding pieces and moving them around to where matches and chains will begin.

Which is to say that, while Rescue mode is the primary single-player mode, there’s no shortage of Tetrisphere to be played. Unless we’re talking about the ability to actually play the game, which at this point requires original hardware or a taste for emulation. Nintendo has never re-released this one, despite its uniqueness and quality.

That’s a real shame, but it’s absolutely worth unearthing a copy and playing it. You can listen to Neil Voss’ fantastic soundtrack while you wait for it to arrive, or really, while doing anything. The electronic-heavy soundtrack was so obviously great even at the time that it received a spotlight feature, “Composing Tetrisphere,” at IGN 10 months after the game released for the N64. And if you’ve played Tetrisphere before, or at least hit play on the embedded soundtrack video from earlier in this feature, you already know why IGN bothered to tell that story. It’s the perfect marriage of sound and sight, and you get to pick whichever of the game’s many, many bangers you want to be playing as you puzzle solve from the main menu, too. Check them all out, even if you’ve got an immediate favorite. You’ll find others.

Sadly, the combination of being on the N64, with its comparatively lower install base, and Tetrisphere being Tetris, but weird, kept it from being a huge source of sales. H2O Entertainment announced during 1998 that it had sold 430,000 copies — not bad for an N64 game, but not great for a Nintendo-published one when you consider that 37 of the 51 million-sellers on the N64 were published in at least one region by Nintendo. Everyone was pleased enough with the results, though, that H2O would co-develop the more straightforward N64 Tetris release, The New Tetris, in 1999, alongside Henk Rogers’ Blue Planet Software, his successor studio to Bullet-Proof. Voss returned as composer for that, because of course he did, did you hear what Tetrisphere sounded like? The New Tetris also isn’t in Tetris Forever, or Nintendo Switch Online, which I am prepared to be a problem about in the future if necessary.

Give Tetrisphere a chance if you’ve never played. There’s a whole lot going on here, and while it’s not exactly Tetris, the name doesn’t matter. This is a hell of a puzzle game in its own right, and on the short list of follow-ups and Tetris-likes that the series’ original creator ended up having a hand in. Whatever rights’ issue has kept it from every platform since its original release in 1997 doesn’t change any of that.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.