Re-release this: Trouble Shooter

Known as Battle Mania in Japan, this shooter is short, sweet, and loaded with personality. It's also never been re-released, and wildly expensive.

This column is “Re-release this,” which will focus on games that aren’t easily available, or even available at all, but should be once again. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

The Sega Genesis and Mega Drive are home to a ridiculous number of shooters, to the point that you had reviewers of the day sometimes complaining about yet another STG on the system. It was the perfect platform for this type of game, though: high speed, lots of sprites on screen, and audio hardware that could make the music to go with all of that. For that reason, it was the obvious choice for something like Vic Tokai’s Trouble Shooter, aka Battle Mania, but there was more to that pick than just the hardware itself. There is also that the game’s director, Takayan, didn’t like Nintendo very much.

That’s not some guess as to his feelings on Sega’s 1990s rival, either, despite the fact that, with a couple of specific button presses on the Mega Drive version of Trouble Shooter, you can see an animation of the game’s protagonist stomping on a Super Famicom. It’s that Takayan volunteered that information himself in a 2004 interview contained within the book Lost Games.

He didn’t go on at length about it. Just a casual, “I don’t like Nintendo,” and then it was on to the next thing. Takayan, as a member of Vic Tokai, had worked on Nintendo platforms for years in the 80s, and wasn’t alone in not liking the Big N’s big-stack-bully approach to being on top. But you don’t usually hear developers just like, say that. Instead, they just did things like quietly head over to Sony’s Playstation when it became clear that Nintendo’s hegemonic rule was no more, pleased to be free of their various contractual rules and restrictions.

So, Trouble Shooter/Battle Mania might very well have been on the Genesis because it made more sense for the game that Takayan wanted to make, in the same way Gunstar Heroes had to be a Genesis title for Treasure to make the title the game they had envisioned. It certainly wasn’t because the Genesis team got bigger budgets — the reason for that secret Super Famicom animation existing in the first place was because Takayan was mad that Vic Tokai’s SFC teams got bigger budgets to play with than the Mega Drive ones. It was, at least a little bit, because Takayan was a Sega guy who liked developing for Sega boards and hardware, and when he had a 16-bit arcade prototype sitting there unused that he wanted to put on consoles, there was only one choice for it and him.

In that same interview, Takayan reveals that he was put in charge of the Super Famicom team at Vic Tokai a little before he left the company. He really, really did not want to leave Sega hardware behind, especially not for Nintendo, which also explains why a third game in the Battle Mania series was planned for the Dreamcast. But only by Takayan himself: according to him, Vic Tokai didn’t want him making a second game, never mind a third, but their hand had been forced by the first one being just popular enough to justify a sequel. So all there is of that game is a design document, to this day. It’s kind of a miracle we got any Battle Mania, really, since Vic Tokai fought Takayan at every step of the process: he didn’t even have a team working on the game with him until people started coming over, one at a time, to pick up a responsibility here and a job there, and suddenly he was the director instead of doing it all on his own. More would have been great, but let’s be thankful for what we managed to get, considering.

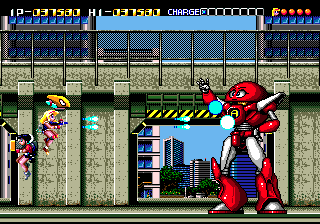

Play just a little bit of Trouble Shooter, and you’ll notice that this is all very much over the top. That’s meant in a complimentary way: you play as a teenage girl, Madison, who is a “Trouble Shooter” — as in, you’ve got trouble, she can shoot it. Her partner is Crystal, whom you do not directly control other than what direction she’s firing in, and they drive around in this very loud-looking red car filled to the brim with weapons, except for when they’re flying with the jet packs strapped to their backs. They’ll fight off monster-looking robots, blast through enemy fire, avoid and blow up enormous saw blades designed as traps, defeat huge robots that look like they belong in a comic book or tokusatsu programming, and… listen, one of the bosses is a big robot on an exercise bike that shoots near-endless laser orbs out of shoulder-mounted launchers. Is the exercise bike powering the enormous battleship the stage is based on? It’s unclear, but it also doesn’t matter. The point is that it’s a goofy visual, which seems to be a lot of what drove how this game looks. This is complimentary, by the way.

As has been pointed out on many occasions, Trouble Shooter pulls a bit from Dirty Pair in terms of the general look and vibe of its protagonists. Not in an exact matching way, or anything, but Dirty Pair did feature a pair of “Trouble Consultants” who were teenage girls, who also blew up pretty much everything in their path on their way to completing their mission. Considering how much else here is a loving nod to a specific form of media that the team at Vic Tokai enjoyed, it’s not a stretch to say that there was at least some Dirty Pair influence here. No one is accusing anyone of a ripoff: homages are a thing, and since all of one (1) video game was ever adapted from the Dirty Pair franchise, other studios had to take matters into their own hands.

The real proof that Vic Tokai’s team here knew ball was that the third stage has the titular trouble shooters encircling a massive battleship for the entirety of the level. Pulling from Dirty Pair? Great, appreciated. Tokusatsu? Also awesome. Letting everyone know that you, too, enjoyed R-Type? You’ve earned my respect.

So, the game is just great fun, and at six stages — none of which are arduously long — it doesn’t overstay its welcome in any way. It manages to stand out in a crowded shooter space to this day because of a few of its core mechanics. For one, you don’t have bombs that clear the screen, or a limited use special ability. You pick one of four special weapons before each stage — a powerful vertical laser, horizontally traveling electric bursts, a handful of missile barrages that fire from you and through as much screen remains to your right, and encircling orbs — and then that weapon has to charge up. You can use it as many times as you want in a level, basically, but only if it’s fully charged and ready to go. And if you happen to try to use it before it’s charged, the weapon shorts out and you have to start the charge process again. Luckily, the charge meter changes color when it’s good to go, so even with a quick glance you can tell: if you see blue, it’s still charging, but red means ready.

In addition to this, you also have the second of the Trouble Shooters, Crystal. She has a different type of blaster than Madison, and while it can’t be upgraded, it’s already pretty powerful. She fires when you fire, and she moves along with your movements, but you can reverse her direction by pressing the C button, to get her to either (1) help you rapid-fire something in front of you to death or (2) stem the tide of foes coming from behind, either because you can’t get behind them yourself, or because you’ve got enemies coming in from both directions. This, combined with an upgradeable option that starts out as just another forward-firing blaster but can become a rotating, bomb-dropping shield of sorts.

Madison’s weapon can be upgraded, and maintains its power unless you die. This is actually another important thing going on with Trouble Shooter: there are no lives. You’ve got just the one life per credit, and all of three credits, even on Normal difficulty. You can take more than one hit, though. In fact, you’ve got a supply of five hit points rather than a health bar. After each stage, you gain a health point, so if you manage to go without taking any damage, pick up the health recovery items, and get that bonus point of health, you actually end up with maybe 8 or 9 health points. You’ll need them, however. While Crystal is immune to damage since she’s basically an option in teenage-girl form, Madison is a large sprite in (purposefully) cramped levels, being fired at from multiple directions. You’re going to take some damage sometimes.

The levels also don’t have checkpoints, so you need to complete each one without dying in order to get to the next. There aren’t any passwords or saves, either, so, you have to learn patterns, you have to dodge, you have to find the special weapon that’s right for you or for the stage you’re in or both. It can be a difficult game that becomes much easier — though still a challenge — if you figure out what it’s asking of you, and then store that information away for your next play. (Veterans of the genre might find it easy at times if they’re used to having to take no damage and not finding extra lives as regularly as this game dispenses health, but there’s a Hard difficulty setting you can switch things to if you feel that way.) Personally, I’m a fan of the versatility of the Lightning Storm, but you might have your reasons for selecting one of the other special weapons because how you deploy it keeps you from taking damage more often, like the Lightning Storm does for me.

Each level’s setting is completely different from the last, and they’re all played a little differently, as well. Stage one has you out on open road, flying through a city. Stage two has you diving deep underground in some kind of facility, scrolling vertically instead of horizontally, and downward. Stage three is the aforementioned battleship stage that has you go around and under and behind and above a massive vessel. Stage four has you infiltrating the Blackball’s — the antagonist — secret base. Stage five has you escaping said base, over the ocean, now with the prince that you rescued from Blackball in tow and armed with his own blaster.

This one plays differently than the others for that reason, specifically: whereas Crystal follows your movements a bit and can be flipped back and forth, the Prince mirrors them, which means you need to figure out where it makes the most sense to place yourself in order to place him while fighting enemies. While you’ve got the prince around, you do not have your usual special weapon, since those are picked before each mission is undertaken, but in this case, “escape” isn’t so much a mission as a thing you need to do. The design of the game as a whole takes these sorts of things into account, and it’s a large part of why the stages not only look, but feel, distinct from each other.

And then there’s the final stage, which has you, for most of it, soloing as Madison, because the crisis had supposedly been averted. Except you didn’t have a real multi-stage final boss fight to that point, did you? Survive the first two rounds of that with just Madison, then you get Crystal back for the third, which features the largest boss of the game to this point, as well as auto-regenerating health. For you, not the boss: consider it a reward for getting to this point, and through the first two-thirds of this stage without either a special weapon or any options, human or otherwise.

You then see the ending celebration play out almost exactly the same as it did before, dialogue and all, except now there’s a giant hole in the wall where Blackball had burst through the last time. One final screen that reminds you that this game is off the wall in the best way possible.

There’s only one real issue with Trouble Shooter — besides its inferior North American cover art that messed with the vibe of what was going on inside that box — and that’s the fact it has never been re-released in any way since its initial one, besides a port to Vodafone’s Java-based phone platform in the early aughts. Which means that, in the present, a copy of Trouble Shooter — game only, no manual, no box — will run you on average $110 secondhand as of this writing. It’s actually sold fairly regularly in this form, though, with one sale per week per Price Charting: people are looking for it and want to play it on original hardware. The complete price is over $300; just the box or manual by themselves cost much more than brand new video games do.

Vic Tokai left the game business in 1997: their game development and publishing was always just an offshoot for a much larger company that was involved in cable television and communications. That corporation still exists today, known as Tokai Communications Corporation, but the game’s portion remains out of commission. Somehow, their game library hasn’t become a major focus of acquisition or modern limited release reprints or anything of the sort, which is odd, since they seem perfect for that sort of thing. Which means, unless something changes, emulation is your best bet for experiencing Trouble Shooter, and its even rare, Japan-and-Korea-only sequel, Battle Mania Daiginjō. Which, for reference, sells for an average price of $624 used, except instead of one sale per week, this is once per year. There aren’t many copies out there, and nearly as few people willing or able to sell or acquire them.

A Battle Mania collection would get a lot of attention: niche as these games are, they’ve got a real reputation for quality, and are pretty much exactly the kind of games I’d run to an editor about featuring as obscure gems if they were to get a re-release in the present. So, whoever has the power to do so, make it happen: more people should experience Takayan’s dream game here. Even if you do like Nintendo, yourself.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.