Reader request: Bahamut Lagoon

For a number of reasons, Bahamut Lagoon is a game in need of a modern-day release.

This column is “Reader request,” which should be pretty self-explanatory. If you want to request a game be played and written up, leave a comment with the game (and system) in question, or let me know on Twitter. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

You know a game has something going for it when it has some incredibly frustrating mechanics and yet, you want to push through and finish it, anyway. This isn’t a thing that happens to me all the time: there are thousands and thousands of video games out there, and if one I’m playing isn’t speaking to me, I simply put it down. Sometimes I go back to it and try it again, but there are also times where, no matter how good people tell me the game as a whole is, I just leave it behind forever. Other times, though, a game has enough going on that, despite my annoyance at whatever is bothering me, I want to keep playing, to see what else the game and its world and its characters have to offer.

Bahamut Lagoon is one such game. It’s a narratively driven strategy RPG from Squaresoft, one that, to this day, remains a Japanese exclusive Super Famicom title. That is, of course, unless you play one of the many fan translations out there. Bahamut Lagoon came to my attention early in 2021, thanks to a Vice feature by Patrick Klepek on Near, a legend in the emulation community who spent over two decades perfecting their vision of Bahamut Lagoon. Near, tragically, would take their own life later in the year, in response to horrific, incessant online bullying and harassment. You don’t need video games to find a world full of monsters.

While there were other completed Bahamut Lagoon translations out there well before Near completed their own, the latter is what I gravitated toward after reading up on the 23-year journey to translate the Japanese RPG. It went well beyond the other localizations, as it made changes that improved the actual look of the text boxes and such, as well as additional tweaks that made it so it would not have fit on its original Super Famicom cartridge any longer. I figured that this was meant to be the definitive edition of Bahamut Lagoon, so why play any of the others?

That Near felt so strongly about perfecting this fan translation and the quality of the game itself is part of what pushed me to keep playing, even as some of the game’s mechanics, AI, and characters frustrated me. There had to be something here worth discovering, worth experiencing in full, and I was determined to figure out what it was. It’s not something you necessarily find in the game’s early hours, either, but that’s because this is a lengthy story in a game that (for the era it’s from) had plenty of time to tell it. One where you think you are living the protagonist’s story because you control them, but in reality, the star of this particular tale is someone else in your party, and you, like your playable character, are watching the tale unfold in front of you.

That is not to say that the appeal of Bahamut Lagoon was lost to me until I was already deep into it. From the jump, I could see why this was considered something of a lost classic — “lost” because it never released in North America. The battle system calls to mind a number of other games. It’s a tactical RPG that will find you moving around a map to defeat your opponents before they can defeat you, and each side takes their turn in full before the other goes. That particular setup calls to mind contemporary games like Fire Emblem, which, in North America, had no presence whatsoever on the SNES, but on Nintendo’s Super Famicom, there were three FE titles, one of which had already released by the time Bahamut Lagoon came out in February of 1996. Bahamut Lagoon had its own mechanic, though, other than FE’s permadeath, and that was dragons.

Well, it has two notable mechanics, but let’s start with the dragons. Each of your characters on the map also has a dragon that they fight alongside. You do not control the dragon directly, but instead, it will either “Come", or “Go,” or “Wait,” depending on what you choose in a given turn. You don’t have to select an option each turn, but you could, if you wanted to: otherwise, the dragon will maintain its orders from turn to turn until you change them. These dragons act independently, other than that somewhat general order. If you tell them to come, they’ll follow their master closely, attacking enemies within range, but not actively seeking them out. If you want the dragons to hunt, then select go, and they’ll go where they feel they are best utilized — which might be extremely far away from your characters, and therefore, any possible healing. Ordering them to wait should be pretty self-explanatory, and is the best way to keep a dragon with low health from running off into a battle that will end poorly until you can heal them.

The dragons are extremely cool, but also a major source of frustration. They do not make the best decisions, even if you plan things out on your end well, and will often attack foes they have no business attacking, using attacks they should not. Using an elemental attack a foe is strong against, for instance, will actually heal that opponent, so you can imagine how frustrating it is when a dragon decides to attack using fire-based attacks on enemies strong against fire, when they could have just as easily used a non-elemental attack instead. It becomes a thing you need to guard against, the dragons’ lacking sense of strategy, and while you can certainly negate it to a degree, something slipping through the cracks could very well end a battle for you, and it might not even be your fault.

That being said, the dragons are overall a net positive. You can feed them in between missions, and what you feed them will alter their strengths — feed a dragon a lot of Fire Grass, and they will have stronger flame attacks — as well as what kind of dragon you actually have. The dragons evolve depending on the kind of items you are feeding them and how many of them you’re handing over as dinner, and changes to the dragons, in turn, impact the characters controlling them: as the dragons bounce from element to element, or type to type, it can impact the kind of magic available to the party controlling them. So, don’t accidentally turn your healing dragon into an attack dragon, for instance, if you were happy having a dragon that focused on keeping your parties alive. And don’t let your dragon get itself killed mid-mission, either, as that will keep the party that was controlling that dragon from being able to utilize magic the rest of that stage.

I keep mentioning “characters” and “parties,” so I should clarify: those parties are actually the second notable mechanic. Those who have played games in the Ogre franchise will be familiar with the idea of a strategy RPG that has you building out entire parties represented by a single character on the map: that’s what Bahamut Lagoon does. You control the individual actions of those characters, however, rather than having the AI fight for you, as it does for the dragons here and as it does for everyone in, say, Ogre Battle 64. If you build parties that all specialize in one thing — like physical attacks — you can earn them a bit of a buff that enhances that skill further. Or you can try to balance a party out, sacrificing the buff in the process, but allowing for a healer to always be present in your party that is going to spend time attacking everything in its path.

You can either attack from long range on the map using some skill or spell that one party member has, or you can attack in what becomes a more traditional turn-based JRPG setup, by getting right up next to an opponent and challenging them to fight. There are pros and cons to either approach: you will have to make your decisions with situational context in mind. You gain less experience for fighting opponents from a distance, which will be much more noticeable if you actually manage to kill someone in an opposing party while lobbing a fireball at them from afar. On the plus side, though, you can attack from range without your characters suffering any damage in return, so it can make sense to have your weaker parties with ranged magic attacking foes from a distance to soften them up for the eventual face-to-face kill, especially since ranged attacks have an area-of-effect that has them impact multiple enemy parties at once.

This tactic keeps your ranged parties fresh and healthy, and gives them a chance to pull at least some experience points that they otherwise would not be able to gain from combat, being dead from facing tougher opponents head-on and all. You will do so much more damage in a face-to-face battle, because all four party members will be given the chance to attack, rather than just one of them casting a specific spell or using a specific skill. And, you might even get your dragon to assist with a magic attack to kick things off, too.

Combat is even deeper than this, though, as you can also impact the environment with elemental attacks. If an opponent is in the woods, then set the woods on fire: your enemies will take fire damage until they move, and if you’ve managed to surround them so they can’t escape, well, even better. You can also destroy buildings, bridges, and so on, or even make new bridges by freezing water with ice attacks. It’s the kind of thing that might seem small, but utilizing tricks like this might also be the difference between winning and losing on a tough mission: it’s worth exploring all of these possible advantages in order to ensure victory. And, if nothing else, it can pay to be thoughtful about your own safety. Maybe don’t set the woods on fire when you’re in them, or hang out in said woods if you’re facing off against a lot of fire-wielding opponents.

Between having six characters of your own to move, and each of those having a dragon that takes its turn, and the battles sometimes being full-on turn-based affairs instead of just a quick attack on the map, you can probably imagine that each stage in Bahamut Lagoon takes some time to complete. They take even longer than you think, given the game’s propensity to have the attacks of both you and your opponents miss or outright fail to even be cast: this, combined with the dragons’ affinity for sometimes not realizing their actions are strategically lacking, can make some missions incredibly frustrating to complete. I had a hard time playing more than a mission or two at a time for a while, because as much fun as I was having with the battle system, and feeding dragons, and the early plot focused on a rebellion against empire, frustration does build up over the course of 30 minutes to an hour of a single map when characters are constantly missing attacks and prolonging the whole endeavor.

Bahamut Lagoon, too, suffers a bit from some pacing problems because the game is constantly requiring that you hit confirm. In classic Fire Emblem games, you can get up and go make a sandwich when the enemy is taking their turn if you want, or check your phone, or whatever you want to do to kill time. Hell, I played other video games on my 3DS while waiting for the AI to do their thing in Genealogy of the Holy War. And in more modern Fire Emblem games, you can just press start and skip the entire enemy turn, and the only interruption you’ll see is if they kill one of your characters. In series like Sega’s and Camelot’s Shining Force, the turns of your party members and those of your enemies are not separated by side, and instead are based on statistics, so there is no wait period at all: just a constant, one-character-after-another setup that ends when the map does. Bahamut Lagoon, because of its dual attack nature, requires your presence during the enemy’s turn, as you might need to set your entire party to defend in a face-to-face battle.

That part is understandable, but that the game also requires you to manually advance the screen after every action that sees experience doled out, whether it be from a head-on or ranged attack, makes it difficult to distract yourself in any way, and just reinforces that you are sitting there doing nothing. You spend a lot of time waiting for your opponent — who has squads much larger than yours — to finish what they’re doing, and can’t occupy yourself otherwise until it’s over, even if you are not required in any face-to-face battles for decision-making purposes. It’s annoying, and is a system that does not respect your time.

And yet, I did keep coming back, despite that disrespect. The dragons, even with the frustrations I have with their lack of reasoning skills, are a lot of fun to deploy, and when they do what they’re supposed to and act as the final hammer blow, it’s extremely satisfying. The game gives you the option in between story missions to go play sidequests that exist in part for additional challenge, but also so you can gain some levels with the characters and the dragons that need the boost, before you progress the story any further. The strategic element inherent in a battle system that has you balancing ranged attacks with face-to-face ones tickled the same part of my brain that loves making the life-and-death calculations in Fire Emblem. And the story starts out a little basic, sure, and characters like Matelite are nowhere near as entertaining as comic relief as Square might have envisioned them to be — a real shame since the guy barely ever shuts up and is always interjecting himself — but it evolves, like the dragons, into something else entirely.

Vague spoilers to follow: The damsel in distress you set out to save isn’t in as much distress as you were led to imagine, and it turns out that you are witnessing their story throughout this game, not that of the character you directly control at all times, Byuu. Byuu is a witness to the game’s events much like you are, as far as the narrative goes. You have some measure of control over their responses, but those just present different dialogue options for the most part. The story of this game is about Princess Yoyo: your attempts to rescue her, the fallout from that decision, her growth as the game goes on, and her destiny as a summoner of dragons.

It helps, too, that Bahamut Lagoon is easy to listen to and to look at. This game released in 1996: that’s a pretty late-life game for the Super Famicom, and Bahamut Lagoon looks the part. Think back to 1991’s Final Fantasy II (officially FFIV) on the SNES: the in-battle sprites were larger and more detailed, but on the map, they were all tiny, and an inspiration for the kind of super deformed art you see in a lot of remakes and retro-style 3D titles these days. Then Final Fantasy III (VI) rolled around in 1994, and the character sprites on the map were the same as those found in battle, and both were more detailed than what FFII was able to produce three years prior. Two years later, Bahamut Lagoon released, and the difference between the sprites in that game and the sprites in FFIII are equivalent to the difference between III and II. Except the starting point for Bahamut Lagoon’s map sprites are ones that look like FFIII’s, while the battle ones are highly detailed, significantly larger renderings. Here’s what a map looks like in Bahamut Lagoon…

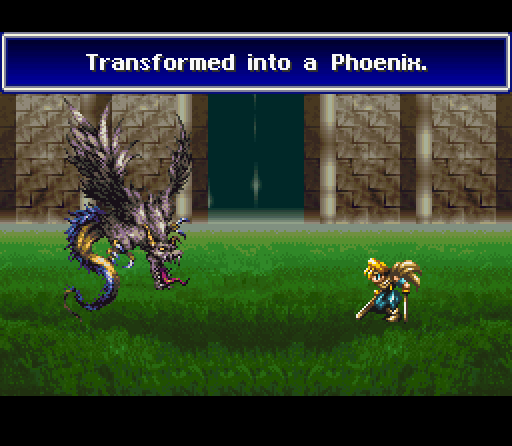

…and here’s what those sprites look like in their battle form:

Look at all of the detail on your party members, seen on the right-hand side of the screen. That kind of attention to detail was traditionally reserved for enemy sprites in Squaresoft’s games, with your characters all kind of being constrained to a specific box where nearly everyone was the same height and width, and lacking in on-screen detail that could only be seen in promotional and concept art. Not in Bahamut Lagoon, though: these characters all look distinct, they’re all sized differently despite being similar, axe-wielding and armor-wearing classes, and they’re all animated in their actions, too. It’s really a gorgeous example of what the SNES/Super Famicom was still capable of, and the kind of thing that makes me annoyed that, sometimes, developers and publishers and console manufacturers move on to the next thing before we’ve truly mined a system for all it can provide. The N64 would release later in the same year that brought us Bahamut Lagoon, and Nintendo was late to the fifth-generation party.

Not just in the quality of the art but in the imagination of it is where Bahamut Lagoon shines. You fly around on an airship, because it is a game released in the mid-90s by Squaresoft, but the airship is actually a floating island with a fortress inside of it. The dragons live on the surface of this island ship, and deploy as necessary from there. You can feed the dragons up above, or spend your time in the interior of the island, speaking with comrades and buying weapons and items. You might never have played Bahamut Lagoon before, but you’ve probably seen nods to it in other Square properties: Final Fantasy X-2’s airship, the Celsius, is a direct nod to this floating island airship, which in Bahamut Lagoon is named Fahrenheit, and Final Fantasy X’s own plot structure and some characters were highly influenced by BH, too.

I mentioned the music, and it is a standout. Noriko Matsueda, known for her work on the Front Mission series as well as the aforementioned X-2, composed Bahamut Lagoon’s soundtrack: it was her first time as the primary composer on a game after working as part of a team on both Front Mission and Chrono Trigger, and she crushed it. Everything fits where it’s used, and enhances the atmosphere of the scene, be it battle, flying around on the Fahrenheit, seeing the story progress, or simply walking around preparing for your next mission. The first battle theme, in particular, successfully evokes the intended feeling. You are fighting with dragons alongside you on an island that is flying through the air, and this is what that should sound like in your head:

You have to love a soundtrack that enhances the narrative and the feel of a game, and while soundtracks matter in basically every game type, getting them right in a JRPG — in what is supposed to be a grand tale that evokes emotion and tries to grab hold of you, where music is going to repeat, and often — nailing it matters even a little bit more than usual. Bahamut Lagoon might have some faults, as I’ve highlighted, but none of them have to do with the game’s art, be it drawn or composed. And the flaws that do exist didn’t keep me from continuing to play, either, even if it did take me awhile.

Bahamut Lagoon absolutely merits a modern release. In part because the ambition of the game’s system is such that, with few tweaks to those systems, it could be released now and still feel fresh. It also could use some minor updates to work on the bits of frustration I focused on, though: improve the AI a bit, cut down on the weird high rate of misses and failures of certain kinds of magic, make it so you can skip through the enemy’s turn until your attention is required, a la modern Fire Emblem, etc. Otherwise, though, Bahamut Lagoon has an engaging story, wonderful art and music direction, and a deep battle system that is just fantastic when it works as intended. Also, dragons. Can’t forget about the dragons.

Square loves a remake, so that Bahamut Lagoon has been left almost entirely to enthusiast fans is somewhat alarming, but the company’s seeming disinterest doesn’t change the fact that Bahamut Lagoon should be released worldwide, either localized in its original form or given a more modern makeover with the kind of changes listed above to ensure it’s something of a throwback hit this time around. It took me some time to work through it, but I’m glad I did so, and I’d do it again in a heartbeat if it got a more official update, too.

Thanks to @WordsandBeer on Twitter for the game request

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.