Reader request: Mega Man Legends

Mega Man went in a completely new and wonderful direction that the world was maybe not yet prepared for.

This column is “Reader request,” which should be pretty self-explanatory. If you want to request a game be played and written up, leave a comment with the game (and system) in question, or let me know on Twitter. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Most people have an image in their head, an expectation, of what they’re going to see when they fire up a Mega Man game. It’s going to be sidescrolling, there’s going to be an emphasis on taking the special abilities of bosses and using them against other bosses, and the games are going to be as fast-paced as they are full of bottomless pits and instant-death spikes. This is how, at their core, many — most — Mega Man games work, whether we’re talking about the original series, or X, or Zero, or ZX.

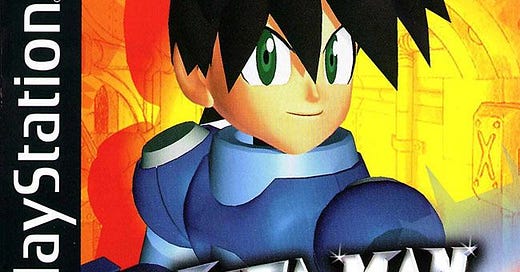

Not every Mega Man subseries is like those, though. They’re not all riffs on the classic formula first introduced on the NES in 1987: the first subseries to truly change what Mega Man was and could be was Mega Man Legends, the inaugural entry of which debuted on the Playstation in Japan in 1997. Rather than a sidescrolling action platformer, Mega Man Legends is a 3D, third-person shooter that’s also an action-adventure game. The version of Mega Man you play as is known as Mega Man Volnutt, and [gasp] he’s not wearing his helmet. He eats meals, he sleeps, he talks, he hangs out with friends, he has what you could describe as “anime hair,” and he’s got a young girl anti-hero with a crush on him trying to kill him to deal with those feelings. It’s not very Mega Man-like, is the thing, except all that should mean is that “it wasn’t like Mega Man to that point.” That Legends was given just a few games to explore this other, different side of Mega Man is a shame, because Capcom built something special here.

This change to the series, in its gameplay and presentation and tone, was not always well-received. The Playstation edition fared a bit better than the Nintendo 64 and PC versions, but even that held a rating of 74 percent on GameRankings: reviews of the N64 version, such as IGN’s, complained about how the original was “a poor experience” on the Playstation, and criticized the graphics, controls, camera, and “poorly mixed elements from the action and RPG genres” while scoring it a 4.5 out of 10. There are some complaints to be made about the camera, sure, and the controls suffer a little bit from an era where dual analog sticks didn’t exist yet and teaching your hands how to make up for that with shoulder buttons didn’t always click right away, but there’s nothing deserving of those negative descriptions within Mega Man Legends.

Its greatest fault is that the world simply wasn’t prepared for this kind of game yet; looking back now, 25 years after its North American debut, and it’s pretty easy to slot this in with other Capcom projects like Lost Planet or Dragon’s Dogma that should have taken the world by storm, but instead released years before the world was ready to embrace them for their excellence and ambition. Not every ahead-of-their-time, slightly awkward experiment of Capcom’s is going to thrive like Monster Hunter did nearly out of the gate, but the disdain that exists for projects like that sometimes is just so strange, especially when hindsight shows the developers to have been ahead of the curve.

Mega Man Legends is a sandbox-style 3D game, released in 1997. Shenmue, also considered wildly ahead of its time, arrived in 1999 on the Dreamcast. Grand Theft Auto III didn’t release until 2001, on the Playstation 2. The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind arrived in 2002, and the first two Elder Scrolls entries (1994 and 1996) were also open-world, but the earlier ones were just for computers, not home consoles, where the technology was a bit ahead of what you found on Sony or Nintendo or Sega’s platforms. The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time — considered one of the premier conversions from 2D to 3D in video games — wouldn’t release for 11 months after Mega Man Legends’ late-1997 debut in Japan.

There wasn’t any kind of normalization for a sandbox-style, open-world game when Mega Man Legends arrived, and one of the earlier, widely available entries for consoles being a Mega Man title — which, spin-offs aside, was pretty set in what it was going to be for the first decade of its existence — just seemed to weird people out. This isn’t just conjecture, either. Keiji Inafune, producer on Mega Man Legends, said in a 2007 interview with Gamespot that, “It was a bit too early for its days. Ever since then, people started saying that 'Inafune's ideas are seven or eight years too early.' It was a sandbox style of game, kind of like Grand Theft Auto. One has Yakuzas and the other has robots, but it's kind of like the same. If we made it at the present time in modern quality, I believe that it would have sold a lot better.”

Many of the contemporary reviews that did praise it were still being hesitant about it: Next Generation labeled it a “diamond in the rough,” but did so while saying that it didn’t have the graphics or gameplay hooks to grab the gamers without the patience to discover said diamond, and scored it a 3 out of 5. So, even while IGN — in its Playstation review — awarded an 8.4 (and stated that it “may change the way we play” Mega Man games “forever”), and Game Informer an 8.5, the overall average score for the PS release still sat at 74 percent. Which is not a score for a bad game, mind you, but worth pointing out because of how much emphasis there seems to have been on what wasn’t perfect in Mega Man Legends instead of what it got right in its ambitious conversion of the long-running series to 3D. Review scores are more trouble than they’re worth and all that, but Mega Man Legends is a much better game than its history with reviews suggests. Basically, if you’re scanning back through contemporary reviews to see if it’s worth experiencing Mega Man Legends, you’re going to be led astray.

Graphics are one area where complaints are seen: granted, the complaints are louder for the N64 port, since the expectations of 2000 were higher than those of 1997, but they still existed. Remember, Next Generation stated that nothing about the graphics would hook players, which is just silly, and the kind of view that stems from the misguided expectations of the era. This is a bright, colorful, cartoony game, and it looks wonderful. Sure, objects in the distance can sometimes pop into view a little jarringly for our 2023 sensibilities, but everything just looks great, and holds up better than so much from the PSX era, in a similar fashion to how The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker — similarly derided for its decision to go with cel shaded, cartoony 3D graphics instead of more a more realistic version of what was seen in Ocarina of Time — has done the same when compared to the games it was judged against in its own era. Hell, there’s still a backlash against things looking “too anime” in the present, so you can imagine what went down when Mega Man decided to go that direction and come off looking like the Pokémon television show people got a hold of the series.

Games simply weren’t doing a good job of animating 3D faces at the time of Mega Man Legends — when Perfect Dark arrived on the scene in 2000, there was voice acting, and no attempt to lip sync or change expressions on the faces of the people speaking. Games like WWF WrestleMania 2000 had an unchanging face on its characters, so you’d end up with a smile plastered across some of the wrestlers’ faces whether they just got their ass kicked or were dropped on their head or whatever. (And, as Abnormal Mapping also brought up, you couldn’t even really make out the faces of anyone in the classic Metal Gear Solid, which released nearly a year after Mega Man Legends, because they were drawn to mostly be impressions of what a face might look like, if someone wanted to take a minute to finish drawing in the rest of the details,) Mega Man Legends, though, would swap in entirely new facial textures, animating faces and allowing for changed expressions with an impressive fluidity to it all, while also doing some neat tricks with alpha-blending and transparency to do things like create a face of a character whose teeth were broken while allowing you to then see the wall behind the space where the teeth used to be. That might not sound like a big deal in 2023, but we’re talking about 1997. This is stuff game designers are still impressed by today, the kind of thing that would get raves if it appeared in a modern indie title, and you had people saying the graphics were lacking.

The character models have all aged very well, thanks to the emphasis on the bright, cartoony style, and the game looks even better with some modern upscaling done to it through emulation, whether you’re talking about the actual gameplay…

…or the cutscenes:

It wasn’t just a more cartoony look, either, but the vibe: that Pokémon show comparison holds up in the tone, as well. The seeming bad guys of the affair, the Bonne family, look and sound like they were ripped right out of that universe, if only it focused more on building huge robots to fight instead of collecting adorable monsters. You could pop Tron Bonne right into a Pokémon game as a rival or antagonist that turns out to be not so bad after all without changing anything about her design, and she’d fit right in. They’re dangerous enough, sure, but goofier than they are harmful, and not nearly as bad or as evil as they might like to pretend.

Not to continue comparing Mega Man Legends to Nintendo franchise after Nintendo franchise, but Abnormal Mapping pointed out that Legends feels like probably the closest thing we got to a Metroid 64: it featured the need for constant upgrades to delve further into the tunnels and caves of its world, and, eventually, you discover that all of these underground segments are fully connected and can be traversed without coming back to the surface. There’s plenty of third-person shooting action, and while there’s way more dialogue than any Metroid game would ever have, and the loneliness that permeates those games doesn’t exist (and would have actually run counter to the vibe of Mega Man Legends), the comparison is a valid and insightful one.

And, in terms of the actual thing, even a hypothetical Metroid 64 was a task no developer seemed up to the challenge of at that time — Capcom getting even some incomplete percentage of the way there is wild enough on its own. Which is to say, it took someone with Capcom’s courage and self-assuredness to attempt such a game, while simultaneously having the same qualities when it came to knowing it was time to step away from the old, popular Mega Man formula, which was admittedly getting a bit tired by this point, with Mega Man fatigue having set in by the time the 32-bit era had begun in earnest. And beyond that comparison, whereas a Metroid 64 likely would have been a conversion of the old style into the new one, a la Ocarina of Time and Super Mario 64, Mega Man Legends was something different: it was a new way of experiencing Mega Man, in every sense of that phrase possible, rather than a reimagining of 2D possibilities into 3D ones like so many other franchises that made the jump during this era. Capcom took their popular, safe series, and moved it into an as-of-yet unpopular, unproven genre, with a new look, new tone, and new narrative that would leave the rebellions and constancy of death behind.

And what did we get for all of this? Well, Capcom put the helmet back on for the cover of Mega Man Legends 2. So, not as much as we should have.

How does it play? You control Mega Man Volnutt, who is a “digger,” which is pretty much what it sounds like. No actual digging is involved (though maybe you do some drilling and blowing up of things to progress), but it’s essentially third-person shooter dungeon crawler, and you’ll do a lot of all of that as you seek to fix your downed ship, the Flutter, while also learning more about the secrets of this island it’s stranded on. Descend, fight, return to the surface before you die so you can sell off goods you found, upgrade existing armaments in a hub or build new ones out of what you found, chat with the townspeople, and then get back to “digging.” As this was before dual analog sticks — even a single one wasn’t exactly ubiquitous at this point — but you’re still needing to control a character within a 3D space with a digital directional pad, you use the L and R shoulder buttons to rotate Mega Man’s body and perspective as you move. This, in conjunction with the D-pad, allows for some pretty smooth strafing and screen rotation: since the auto aim is pretty forgiving, you can run circles around your foes when you’ve got the space to do it, avoiding their attacks while firing off your own.

You can also dive to the side to avoid incoming attacks, jump (and shoot while jumping), eventually dash on rocket skates, and equip upgradeable secondary weapons with limited ammunition that can be utilized in concert with your main weapon, instead of you having to choose one the other to use at a time like in previous Mega Man titles. Fire your main gun — which is also upgradeable through a different method, more on all of that in a bit — when it makes sense, then hit the triangle button to shoot your secondary weapon when that makes sense. It’s not quite an Armored Core VI level of sophistication or anything, but you do have to contend with when to lock on, when to run and gun, as well as which weapons make sense to fire at which times, and against which foes. And hey, there are mechs.

It will admittedly take a little time to get used to these kinds of controls, either for the first time or even if you’re reaquainting yourself with the style of the time. We’re pretty used to a dual analog world now, with the right thumbstick used pretty instinctively to rotate the camera and get us the angles we need, but Mega Man Legends is from a different era. It’s exponentially easier to sort out than something like the original Tomb Raider, and a smoother and more reliable control and camera experience than another contemporary like Burning Rangers, but takes a little more effort to sort out than something like Bulk Slash. If you’ve bothered to put in the time to figure out any of those control schemes, though, whether in the past or the present, then Mega Man Legends will be more than worth the effort required for you.

Something else to get used to is how the game explains very little to you. You get a general sense of some of the systems — Roll tells Mega Man to come to her with the junk you pick up for upgrades, for instance — but much of what you receive for upgrades, or Roll builds for you, or places to go and to explore, people to talk to, side missions to complete… it’s all just kind of there for you to poke at to see how it all reacts to being poked. That’s the real sandbox nature of it all, and it’s an extension of the exploration and experimentation of the 2D Mega Man games, which honestly gave you even less to work with in terms of what was needed out of you or what you could do.

Along these lines, there’s an ethics system in Mega Man Legends, and you just kind of have to discover that for yourself (or stumble upon the book in the library that explains it to you). Mega Man starts out with neutral morality, and as you perform (or don’t perform) certain actions, that morality will go up or down. If you’re popular, you’ll notice it around the island, and you might even get some better rewards from certain missions. If your morality is in the toilet, people on Kattelox Island — the setting for the game — aren’t going to be all that friendly to you, and the shading on Mega Man’s armor is going to darken. Don’t worry, you can’t accidentally kick the dog in the North American version of the game, ruining your morality early on.

Some of these systems feel a little half-baked at times, sure, but they all do work, and they contribute to what was clearly an ambitious title. Capcom didn’t need to design a Mega Man game like this one! They could have just kept moving on along the same kind of Mega Man titles that had kept the series going for its first decade. Instead, they decided to upend the whole thing and go not just in a different direction, but in one that pretty much didn’t exist yet anywhere, never mind for Mega Man. The weapons system, in particular, was a huge leap for Mega Man, and also works out well. Your primary weapon — still a Buster, they didn’t change that — can have different parts equipped to it that change its attack power, rapid fire speed, how many shots can be fired off in a row before a pause (energy), and its range. So the pieces you equip will do things like add two attack points and one range, or three energy and one rapid, or one of three of the bits, and you need to figure out how to best apply them for various situations. If you’ve got enemies at range, well, equip some of those parts. If you’re going to be up close and personal, rapid fire and attack seem like a good focus.

You also will either have made for you, or purchase yourself, various upgrades for your armor. These reduce damage (by 1/4, 1/2, or 3/4, for escalating prices) or make it so you don’t take fall damage, while other equippable items like the jump springs (jump much, much higher and further) or the skates (rocket dash) let change the way you move around the environment. You can buy and upgrade a canteen to hold reserve energy for refilling your health bar, pay to upgrade the health bar itself, buy items that will restore your shielding or replenish your secondary weapon’s ammo reserves… you’ve got a lot of options of things to spend your money, known as zenny in-game, on. And basically a limitless supply of zenny to collect, so long as you feel like exploring the world, completing side missions, or just going underground and blowing up a bunch of enemies. This freedom to go where you feel like and complete the same objective through a variety of means feels pretty normal in 2023, but in 1997? Again, Ocarina of Time wasn’t even out yet, never mind what was to come.

It was a very intentional decision, too, with the idea behind that this was a new style of game, and gamers were getting older, and might not have the same kind of time they did to, as the kids say, git gud. Inafune, in a pre-release interview from ‘97, explained that:

“There’s a bit of strategy allowed in what you upgrade as well: if you’re dying a lot, you can choose to raise your life first, for instance.”

We added dungeons as places for you to get money, and there’s lots of stuff to pick up in the towns, and minigames to play and win prizes from—basically, there’s more than one linear path to progress through the game.

So if you do get stuck on a boss, you can always go do something else for awhile. In previous Mega Man games, even if you were having trouble with a boss, the only option you had was to beat it to move on. For a kid, that’s no problem, they’ll just tough it out and persevere until it’s done. But an adult playing the same game will probably just give up, “this is impossible, I can’t do it.” But this time, in Mega Man Legends, if you find something is too hard, you can always grind for money and that should help you—and since there’s many different ways to get money, it should never feel like work.

Again, this feels pretty normal for 2023: Yakuza/Like A Dragon games have been doing this kind of thing for nearly two decades now, and they’re far from alone. But Mega Man Legends opened it up real early, and for more reasons than just because they could. Legends is still a real tight experience — you can get through the game without bothering to upgrade every little thing, or find every secret, and still wring a meaningful and enjoyable 10-12 hours out of it. It’s just not a one path only, 1-2 hour experience full of dying and retrying the same little stages again and again until you get them right. And if you want to play for much longer and complete every little thing, you can do that, too.

Some form of story has always existed in Mega Man, whether it was restricted to the manual or displayed through a few text boxes early on and late into the games, as was the case with the original Mega Man titles and then the X series, respectively. Capcom had already begun adding in more and more story elements to X, though, with the Sega Saturn and Playstation ports of the 16-bit Mega Man X3 including animated cutscenes, and Mega Man X4 leaning further into that approach as a game developed exclusively for the kinds of platforms that could handle that sort of thing. Mega Man Legends went beyond those growing expectations, though, with loads of dialogue not just for primary characters, but for interactions with NPCs, as well. An attempt was made to make Kattelox Island a living, breathing world, and Capcom was as successful with their attempt as Nintendo was with Hyrule a year later, even if the feat wasn’t given similar recognition.

One area Capcom succeeded in this goal was in the enemy designs. Inafune assigned two different teams to the surface designs and the underground designs, which allowed for a massive distinction between, say, the mecha-inspired robots designed for and by the Bonne family, and the ancient ones you’d find in the ruins, which had more of a “creepy, unsettled” vibe to them. Their designs didn’t make as much intuitive sense, they didn’t have that kind of quality of humanity or kinship to animals to them that mechs so often do, they just seem a little… off. And wrong for the world you know on the surface. There’s one robot you find underneath that, while not quite as unsettling as Resident Evil 2’s Licker for a number of reasons, sure reminds you of a robot version of it. And it’s worth remembering there that Legends came first.

This Mega Man isn’t one forged in the fires of putting down evil robot rebellions or dealing with a scientist bent on world domination, but is instead one who doesn’t remember his past, and is basically just hanging out in what seems to be a post-apocalyptic world that’s trying to fix itself. The bright and cheery nature of the world suggests everyone is doing a pretty good job of things, lack of energy sources aside, but behind the scenes are dark secrets from Mega Man Volnutt’s past unknown even to him, and they’ll rise to the forefront just in time to lead you into the eventual Mega Man Legends 2. It’s all well done, and performed well: again, going with the intentionally cartoony vibe paid off not just on the visual side, but with the voice performances, too, as they fit the visuals and are convincing. Mega Man X’s childlike voice in X4 sounded off because he was supposed to be this hardened survivor of multiple rebellions and attempted genocidal events, and it just didn’t fit. Volnutt’s voice, which makes him seem like a 14-year-old boy or so instead of a grizzled vet, fits the bill better even though it isn’t all that different in actual sound. As far as he remembers, he’s just a guy who likes to go exploring and hopes the ancient technologies of the past don’t try to kill him while he’s doing it, and in his off time he’s just hanging out with a robot monkey and another young teen and her grandfather on his airship. So it works in this context!

Mega Man Legends is a wonderful game that didn’t get the kind of respect it deserved in its day — its reception is described as “moderately positive” on its Wiki page — which led to it getting just a couple of sequels before Capcom dropped it. While the Playstation 3 digital storefront included multiple Mega Man Legends titles in its library, that was two console generations ago, and Sony has made it difficult to access and buy those games even if you did still have one hooked up and capable of the task. Capcom has been making collections of its various Mega Man subseries, though, so hopefully Legends is on the way: hey, if they’re going to re-release all of the Battle Network titles to an overwhelming positive response, then why not give the Legends trilogy a second shot, too?

Thanks to @Spitball_Idea on Twitter for the game request

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

I loved the Legends games as a kid. Great write up and made me feel nostalgic.

We can request games for you to write about?! I'm surprised you didn't reference the cancelation of Mega Man Legends 3, that felt like a big moment in the narratives around the series and Capcom.

There was a period of time where people felt like Capcom hated Mega Man and that was a major reason why, I remember people regarding Mega Man's appearance in Smash 4 as Nintendo doing more for the series than Capcom would. A lot of the anger over the cancelation helped drive attention to Mighty No 9 which brought video game kickstarters into the limelight. Now people like Capcom again, but it felt like they had to earn their reputation back.

It's sad and frustrating how some games just attract a ton of unfair hate. Feels like whenever I find a gaming community a game I like gets used as a punching bag so I lose interest in interacting. Playstation All Stars Battle Royale, Code Name S.T.E.A.M, Kid Icarus Uprising (people came around to that one at least), ARMS, several Sonic games, Xenoblade 2 threads on r/Nintendo were a damn warzone, and so on.

Since I now know I have the power to make requests I'm going to request Joy Mech Fight, somewhat topical though a bit late with its appearance on NSO.