Reader request: Radiant Historia

A time-traveling JRPG with very specific rules about how time travel works, that plays as well in 2021 as it did when it first released a decade ago.

This column is “Reader request,” which should be pretty self-explanatory. If you want to request a game be played and written up, leave a comment with the game (and system) in question, or let me know on Twitter. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

There weren’t very many complaints about time-traveling role-playing game Radiant Historia back when it released in 2011 for the DS, but there was one that popped up more than once in reviews of the Atlus and Headlock title. And that was the game’s linear nature. It’s about time traveling, why is the plot linear, where is the freedom of choice, etc. My short answer to that line of questioning is this: because that’s not the story the game was telling.

Radiant Historia is not an open-world, branching-quest-and-decision-tree kind of JRPG. It is linear, sure: there are correct paths and incorrect paths, and choosing the latter when given the opportunity will end your game and force you to go back in time once again to make the right call. The time travel hook in the game is designed to tell a very specific story, in the same way a book about time traveling, or a show about time traveling, or a movie about time traveling would. It’s kind of weird, to me, for reviewers to agree that Radiant Historia’s story works, is great, and so on, but then also bemoan that it wasn’t actually a different game. The story and the way it’s told are inextricably linked: it’s like complaining that the latest fantasy novel wasn’t released under the Choose Your Own Adventure label.

Now, of course, this is not the same as saying you cannot criticize the design of a game, or that you can’t wish that it was something else. Hell, before sitting down to write this piece, I was complaining on Twitter about Gears of War 5 adding in unnecessary open-world sections to a franchise whose strongest design points are its focused set pieces and tense claustrophobia (and I was right to do it). I mean more in this specific instance, that a story was told a specific way — and we all agree it worked! — but then some of us can’t help but complain that it’s not just like everything else that’s out there, like we’re running down a checklist and have to whine when some boxes go unchecked, even the ones that don’t actually need to be checked. There are plenty of decision-tree, freedom-of-choice games out there already. Radiant Historia isn’t one of them, but what it did, even with “just” a linear approach, was still fresh and new, and feels as intriguing and rewarding on replay a decade after the fact as it did when it first released.

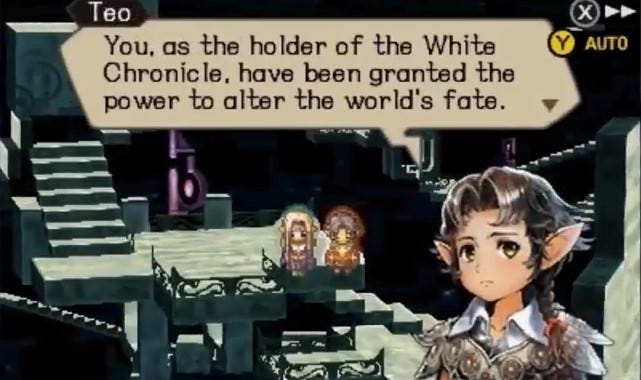

What Radiant Historia did was, rather than go for freedom-of-choice, is explore the idea of living every possible permutation of history over a short but decisive stretch of time in the heart of an empire. You play as Stocke, the wielder of the White Chronicle, a book of unknown origin and power that reveals its ability and purpose shortly into the game’s story. The White Chronicle allows the wielder to travel back and forth to fixed points in time, with the idea being that those points are ones in which the fate of the world can be influenced. As the world Stocke lives in is very close to being decimated by the combination of forever war and still-reversible climate catastrophe becoming irreversible climate catastrophe, there are many, many of these points to travel to.

I should point out that the climate change themes hit hard back in 2011, and they sure do not hit less in the present. Radiant Historia presents a world where humans were meant to be the stewards of the world, protecting it and keeping it full of life, but have neglected their duties in favor of forays into needless technologies that only continue to fuel the fires of war. It is a tale and premise that is, in a word, relatable.

There are, in essence, two core timelines that Stocke will work through, that exist because of a decision point where he must either keep on working for the Intelligence Agency he’s employed by, or switch back to the military he left behind for intelligence work. The game doesn’t have you choose just one of them to work through in order to put a stop to the coming end of the world, but instead, has you work through both. The two timelines are very closely connected, to the point where your actions in one can impact the other, both on a physical level — save a merchant from certain death in one timeline where their fate doesn’t concern your mission, and the merchant will make it to their destination in the other timeline where it is required, for you to progress, that they do so — and on an emotional one. There is a moment where you must convince one of your allies of their will to fight for what’s right rather than to simply take orders like they always have, and as a result, you are able to avoid their unnecessary death at your hand in the other timeline, as they come to the conclusion that they should defect all on their own, as far as they know.

Luckily, Radiant Historia lets you skip over events you have already seen before, so if you’re trying something for the second or third time, or just hopping in to quickly finish off or progress a quest or what have you, you don’t need to go through the entire process again. It helps everything keep moving smoothly and efficiently, and encourages you to explore the past, as well, since the annoyance factor of doing so has been significantly lessened.

There are key items and powers and MacGuffins you can’t find access to but still require in one timeline or the other, but you can find a way to get to them in the other. So you aren’t in a situation where you play all the way through one timeline then switch to the other: you’re constantly going back-and-forth between the two, puzzling out what will let you progress in one and then the other, making notes about places to revisit in order to help as many people out as possible as well as yourself along the way. The two timelines work together, and bleed into each other in a way that effectively makes the combined version of events the true history of the world, even though Stocke and his party weren’t able to actually be in two places at the same time. The White Chronicle allows them to do that impossible thing.

As this is an RPG, with all the experience points and hit points and leveling that entails, you will need to ensure you are not progressing too far in one timeline before going back to the other in order to shore up your abilities. You won’t find yourself grinding in Radiant Historia, which is a positive, but you might find that, early on, if you went the alternative route, for instance, that combat is a bit tough. If you ever think enemies are too difficult, then you can just hop to the other timeline and try to make some progress there, which should get you the experience you need in order to better tackle the issue. Similarly, if you’re low on money, then there are some sidequests throughout both timelines you should be focusing on, as those are tremendous sources of gold and the occasional free piece of equipment, too. Everything from the two timelines really works in concert here.

Speaking of combat, it has enough wrinkles in it to keep you engaged. Enemies appear on a 3x3 grid, and your goal is to not just defeat them, but to do so as efficiently as possible, via crowd management. Enemies do more damage to you the closer they are to your position, so you want to push them to the back of the grid, and you have specific special skills that let you do this. You’ll spend most of the game utilizing skills rather than straight-up attacking, or, at least, you’ll only do your attacking after your skills have set you up to get the most out of those attacks. So, let’s say you have an enemy in the bottom right of the 3x3 grid, another at the top right of it, and one in the top left. You could have Stocke use a directional skill that will bring the bottom enemy to the top, then have Marco (one of your near-constant party members) push both enemies to the back row with a skill of his own, then have Raynie cast a spell that all three enemies are weak to while they’re all smushed together.

After your attacks are over, your foes will spread back out rather than sharing one space, but the hope is that you whittled down their numbers while moving them all to spaces where they can cause less damage to you before it’s their turn to attack. You have significant control over how long these attack sessions you perform are, as the turn order is displayed, and you can manipulate it. If you just have Stocke up next, for instance, before the three enemies you’re facing begin their turn, then you can swap Stocke’s spot in the turn order with one of those three foes, in order to put him in line with the rest of his party. You can also keep on doing this kind of swapping in order to build out the entirety of the 10-turn order with your party, giving you the chance to do what will, in most instances, be a screen-clearing combo for you, or a way to wreck a boss’ health meter. There are downsides to swapping, though: anyone who swapped is more susceptible to critical hits until they take their turn, so you need to be strategic about how you rearrange the turn order.

It’s absolutely worth the effort of figuring out, as you earn far more experience and gold for setting up elaborate combos than you will for just straight fighting and accepting the turn order as is. This is especially important for when you’re trying to catch up some party members who are only with you in one timeline, too: a bit of bonus experience can go a long way toward making them as battle-ready as Stocke, who, as the wielder of the White Chronicle, is with you regardless of which timeline you’re in.

One of Radiant Historia’s strengths is its decision to present itself as something of a throwback to the 16-bit or even 32-bit era of Japanese role-playing games. The DS was capable of 3D and polygons and all that happy stuff, but Atlus and Headlock co-developed a game that felt much more like it was conceptualized in the early-to-mid-90s, on the Super Nintendo or the Sega Saturn. It all makes for some beautiful art that doesn’t feel like it’s straining the system, but also is much cleaner and better animated than a whole lot of what you would have actually found available in the era that it means for you to recall.

Why this is a strength is because, unlike a number of retro-styled RPGs that exist out there, Radiant Historia was, conveniently enough given the game’s themes, interested in looking both backward and forward. Yes, it’s a throwback to the 90s in a whole lot of ways, but it wanted to build on the kinds of RPGs that existed then, not simply ape them and coast on nostalgia. The intricacy of the timeline system feels like a step forward for the genre, and the combat system, too, uses the kind of more sophisticated battle arrangements and strategy that existed in a time other than the early 90s. There are too many retro-styled JRPGs out there that ask and answer an extremely shallow version of the question, “hey, remember the 90s?” instead of pulling off what Radiant Historia did, which is to cause you to recall the 90s, but then present a vision of where this particular style of game might have gone if not for the industry shift away from 2D and, eventually, JRPGs.

It was a little harder to pull a comparison out in 2010, back when Radiant Historia released, but now that there has been such a retro revival across a number of genres, think of it like the JRPG equivalent of what we’ve seen in the return to 1990s-style 2D platformers and Metroidvania games, even in this era of 4K high-resolution where you can see the individual hairs in this guy’s beard processing power. No one is about to say that a platformer like Celeste simply rested on the power of nostalgia: that brought about an aesthetic and particular brand of gaming that had been relegated to handhelds and then nonexistence after the rise of hi-definition gaming, but it came with its own advances for the genre and modern twists, the same as Radiant Historia managed a few years earlier for JRPGs.

Radiant Historia was a critical success, but it also released fairly late into the life of the DS — the 3DS, successor to the DS, released eight months before Radiant Historia — so it didn’t necessarily get all the attention it deserved, even though it was, as a DS title, backwards compatible with the 3DS. An enhanced 3DS re-release, subtitled Perfect Chronology, would come out in 2018 to give it a second chance at life, and it revamped the art while also adding a slew of optional content. New party members, new timelines, new time-based puzzles and quests to work out, and you have the option of leaving it to even be presented to you until the end of the game, or playing it right alongside the core content that’s always been there. The changes in art are severe, so if you were extremely attached to the original style, sorry about that, but the new looks are good, at least: it’s not like they did what occasionally happens in a remaster, where you get cleaner, but less interesting, more generic art to replace what was lost.

Regardless of which version you end up playing, the music is excellent. Radiant Historia was composed by Yoko Shimomura, whom you might know from her many years with Capcom, anything you’ve heard from a Kingdom Hearts game, from Xenoblade Chronicles, from a whole bunch of Square Enix titles, and more. The soundtrack has plenty of bigger, driving numbers — the battle theme in particular stands out, which is good considering how much fighting you do — but the soundtrack is at its best when it focuses heavily on drawing more emotion out through the softer side of things, such as with a piano, like in this arrangement of Mechanical Kingdom:

It’s a beautiful track (in its original form, too) in a game full of fascinating character beats and earned dramatic moments, and as a whole, the soundtrack compliments what’s happening on screen incredibly well. Not a shocking bit of news there, no, but enjoyable nonetheless. It should say something that I sold my original DS copy of Radiant Historia years ago, but kept the short album of piano tracks that came with it. I am a sucker for things like that, but also, the music is great.

Since the re-release of Radiant Historia didn’t exactly come out in the middle of the 3DS’ peak, it’s not the easiest game to get your hands on for cheap — starting prices on Ebay as of this writing are in the $100 range, and boy am I glad I decided to pick up the 3DS re-release awhile back after looking that up. It is at least available digitally on the 3DS itself for its launch price of $40, and that system still has the occasional sale that substantially cuts into that figure: Atlus, in particular, seems to stage one every now and again across most of their digital titles. So, if $40 sounds steep, too, add it to your wish list and wait. It’s worth the price of admission, though: this is a deep and engaging JRPG, one worth both the money and your time, and the latter is the more important point when it comes to something the length of an RPG, anyway.

Thanks to @scottgrauer on Twitter for the game request

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.