Remembering Compile: Gorby no Pipeline Daisakusen

Just before the Soviet Union's dissolution, Japan made video games that featured the actual (and approved) likeness of its then-president, Mikhail Gorbachev.

Compile, founded in the early 1980s, was a standout developer in its day. That day is long past now, however: as of November 2023, it’s already been 20 years since the studio closed its doors. In its over two decades, though, Compile showed off influential talent, and became the start of a family tree of developers across multiple genres that’s still growing today. Throughout November, the focus will be on Compile’s games, its series, its influence, and the studios that were born from this developer. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Compile made a number of puzzle games in their day, and not just in the Puyo Puyo series. Various puzzlers in various subgenres were released in the long running Disk Station series, both before and after Puyo Puyo. Guru Logi Champ on the Game Boy Advance was one of Compile’s last games, while Pochi and Nyaa was Compile’s final title, in the sense they closed while developing it, and it ended up completed by many of the same developers in a temporary studio made for that purpose. Similarly, one of the first Compile Heart titles post-Compile closure was Octomania, a rotating block puzzler with multiplayer.

And then there was 1991’s falling block slash Pipe Mania/Pipe Dream crossover title, Gorby no Pipeline Daisakusen. The “Gorby” stands for “Mikhail Gorbachev,” as in, the president of the Soviet Union at the time of its release. Yes, Compile developed a puzzle game — for the Nintendo Famicom and for the MSX2 and FM Towns home computers —featuring Gorbachev’s likeness, where the central premise of the game was to build a water pipeline connecting Tokyo and Moscow in order to bring Japan and the USSR closer together. And you thought a kindergartner climbing a magical tower and fighting slimes in order to graduate was a weird concept.

Maybe even stranger than the fact Gorby no Pipeline Daisakusen exists at all is that it’s not even the only Japanese game starring Gorbachev to release in 1991. Japan System House developed Ganbare Gorubī for the Game Gear, and Sega published it just two months after the release of Pipeline Daisakusen. That’s an action game where “Gorby,” styled after Gorbachev, uses conveyor belts to send goods outside of a factory to the people waiting for the specific item, be it different kinds of food, first aid, or even a Game Gear. It would be renamed to Factory Panic in Europe and Brazil, since the idea here was on Japan and the Soviet Union’s relationship, and also, you know. Rightly or not, most of the rest of the world wasn’t pro-Soviet Union at this time, and these companies wanted to sell their video game.

Gorby no Pipeline Daisakusen retained its full name for years, though, the re-release of the Famicom version on iOS and Japanese Windows via D4 Enterprises’ Project EGG subscription service cut out the first two words and the likeness so that it’s just Pipeline Daisakusen now. Granted, not a whole lot has changed, since Gorbachev’s likeness was used on the cover of the game and on the title screen, but in the actual gameplay, young girls in Russian-style national dress were shown, with the game’s music chiptune arrangements of Russian classical music. Excising Gorbachev from things didn’t fundamentally change the gameplay, even if it obscured the original mission of the game a bit.

That mission, like the in-game one, was to strengthen ties between the neighboring USSR and Japan. Historically, even prior to the formation of the Soviet Union and dating back to the days of Imperial Japan, the two were opposed, and while there were wars and moments of “my enemy of my enemy is my friend, maybe?” throughout the 20th century, the relationship in general was a cold one. Gorbachev’s time as president of the Soviet Union, though, opened up greater potential for friendlier relations. While Japan’s demand that the Northern Territories — four islands which the USSR took control of during World War II — be returned to them (and the Soviet’s refusal to return them) kept the two governments from working together in a friendlier way or even at all, Gorbachev planned a visit to Japan in 1991, with the potential for a deal that would benefit both countries on the table. Japan maybe getting back the territory they demanded, and the Soviets — in economic turmoil with most of the world against their existence at the behest of the global hegemony — maybe benefiting from Japan’s rise in the worldwide technology market, with the added bonus of not being at each other’s proverbial throats any longer.

The Japanese government needed more convincing about the state of the relationship and how things should be, but, given that there were two different video games featuring Gorbachev’s likeness released in 1991, the year of his visit, it seems pretty clear that the government didn’t necessarily speak for the entire country. Of course, the Soviet Union dissolved later in 1991 before any deal was reached, and then the Boris Yeltsin-led Russian Federation went right back to the pre-Gorbachev hardline stance against Japan and for keeping hold of the Northern Territories. I’m pretty sure that Japanese studios didn’t make any video games featuring Boris Yeltsin.

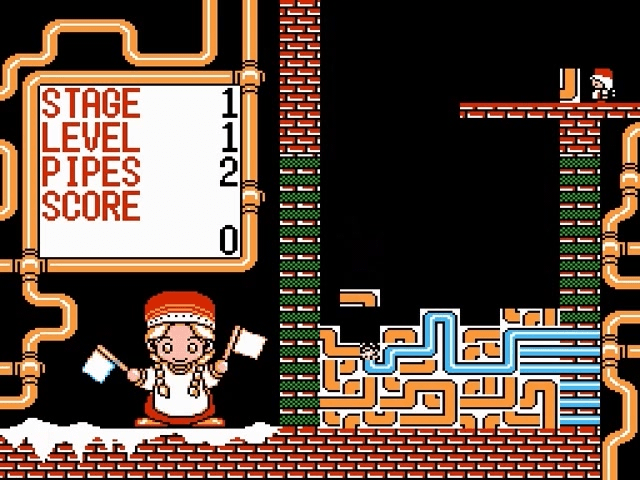

So that’s the background; now, how does Gorby no Pipeline Daisakusen play? If you’re familiar with Pipe Mania or Pipe Dream — the name you know is based on which platform you played it on — then you’re halfway there. Pipes of various lengths and shapes are there for you to connect together in order to connect the inflow pipes on the right side of the play area with the outflow pipes of the left. There are quite a few differences between Pipe Mania/Dream and Pipeline Daisakusen, however. For one, you aren’t picking from a selection of available pipes: they fall from the top of the play area, like in Tetris or Puyo Puyo or Columns or whichever falling block puzzle game you prefer to consider. And whereas the end of a pipe in Mania/Dream was if the liquid moving within it ran out of pipe to travel through, in Pipeline Daisakusen, the issue is whether you’ve had the blocks hit the top of the play area, or blocked off all of the inflow/outflow pipes so that no more new pipes can connect.

These falling pieces are structured as either one large two-space block — a long length of straight pipe, a longer pipe that is angled in one of a few different configurations at the connecting ends — or two smaller pipes in one block. And you have to rotate them and fit them in where they should go, and fast. Luckily, pipes only stay up if they’re supported underneath, so you can effectively “slice” pieces of pipe off if only half of a falling block fits your current plan, just by placing it so there’s no support underneath the other half of the block.

Here’s where the game trips me up, and it’s not a failing of the game design so much as a failing of my brain and how it works. You can’t really plan ahead too far in Pipeline Daisakusen, because once you do manage to link an inflow pipe to an outflow pipe on the other side of the playing field, the pipe vanishes, points are scored, and the remaining “structure” — i.e., a bunch of leftover pieces that didn’t form the pipe full of flowing water — collapses to fill the space. So, if you had most of a second pipe going, and it wasn’t connected to the first somehow, it’s now a jumble lying in a heap. You can build big instead of direct — make a pipe that takes a very indirect route, or splits off in two directions with just one inevitably connecting to an outflow pipe — to score more points, but concurrent and separate pipes is probably more trouble than it’s worth. Or, again, I’m just not very good at this game, but it’s certainly one of the two. What I can tell you is that working from both sides of the play area makes much more sense than just going from right to left: it gives you more of a path to follow, and keeps you from wasting quite so many pieces that will leave you with a mess to clean up later after you do manage to connect a pipe.

To help you out — or harm you, depending — there are a few different items that occasionally are tossed down instead of more pipe. One drills through pipes (or blocks filled by loose water) in a straight line down, clearing one or two columns for you depending on its orientation, which can either be an issue — cutting a connected pipeline before you complete it — or a blessing — opening up some space filled by detritus so that you can then use that space for new piping. You will also get a water item that fills part of the play area with water if it connects to a space that already contains a water block. This will raise up your structure, which you are probably not going to want to do since reaching the top will end your game. However! If you’ve got the space for it, making lines of blue water blocks to be cleared by an eventual pipeline can net you additional points. So there’s a reason to not just waste them by dropping them where they’ll splash harmlessly and dissipate.

You have to complete nine different levels, each requiring a certain number of pipelines to be successfully built, in order to finish the connection between Tokyo and Moscow. You’ll have to familiarize yourself with the various pieces and not just what they directly look like they do, but also what they can do when sliced off or are connected to later on. It’s a lot, really, since, through splitting pieces and reorienting, there are effectively three dozen different pipes to work with. Given how quickly you end up having to make decisions as the game goes on, you’ll need to start feeling where pipes need to go rather than take the time to think it over.

The soundtrack is good, which makes sense: it’s video game arrangements of classical Russian music. Who has ever been upset about hearing Flight of the Bumblebee? The MSX2 version sounds better than the Famicom one, though: it’s a bit less grating on the ears over time, with the FM-based hardware just working a bit better for the sound of these classical songs than Nintendo’s console. You can hear the difference in the two embedded videos: the gameplay one (the first), is from the Famicom version of Pipeline Daisakusen, while the second video is the OST from the MSX2 edition of the game. It’s just a little softer, a little less harsh, than the chippiness of what the Famicom had going on for these classical songs. And this comes from someone who has no real issues with the NES/Famicom sound hardware outside of how it couldn’t always handle playing sound effects and music at the same time, too.

Obviously, Gorby no Pipeline Daisakusen didn’t make it outside of Japan during its original release. Which makes it even that much more of a Compile game: this studio had a knack for making some quality games that the fewest possible people would ever get a chance to give them money for, and “puzzle game featuring the president of the Soviet Union made in an effort to strengthen ties between that country and one the Cold War-era United States threatened to sanction if they so much as economically said hello to the Soviets” certainly qualifies under that banner, and releasing it months before the USSR dissolved is the exclamation point on that vibe. Hell, it’s kind of amazing that the game even happened in Japan, considering American influence there post-World War II led to anti-Soviet sentiments even outside of Japan’s own conflicts with the country, but 1991 had some measure of hope of change in it, at least until the change the world got ended up being far different than what either nation had been hoping for.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.