Remembering Compile: The Guardian Legend

The Guardian Legend is a cult classic, but it deserved so much more.

Compile, founded in the early 1980s, was a standout developer in its day. That day is long past now, however: as of November 2023, it’s already been 20 years since the studio closed its doors. In its over two decades, though, Compile showed off influential talent, and became the start of a family tree of developers across multiple genres that’s still growing today. Throughout November, the focus will be on Compile’s games, its series, its influence, and the studios that were born from this developer. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

The Guardian Legend is a weird game. Not quirky weird, not strange in some unsettling way, but just… weird. The weirdness stems from its design and how relatively unique it is. It’s both a shoot ‘em up, which developer Compile had already put together quite the reputation for, and an action-adventure game with action role-playing game elements, which, less so. It’s not that Compile was new to action-adventure — Golvellius had released in 1987, and was both great and unique in its structure in in its own right — but that the combination of these two genres was a fascinating decision, and the addition of action RPG progression only made it that much more unique.

And, it turns out, one not easily replicated. The Guardian Legend doesn’t stand alone in its mashing up of STG and action-adventure, as Wayforward attempted something similar with Sigma Star Saga in 2005, and Super Star Force actually released a couple of years before The Guardian Legend did, though not with anything close to either the quality or the reputation that Compile’s effort ended up with. NieR Automata, kind of quietly in forums and comparison videos, has built up a little bit of a rep as being similar enough in its structure to The Guardian Legend that it could be considered influenced by it nearly three decades later. Which should give you an idea of the whole “The Guardian Legend is a weird game” thing if you haven’t experienced that but have played Automata.

In The Guardian Legend, you play as the Guardian. At least, in the English-speaking versions of the game: the protagonist’s name is Miria in the Japanese version of The Guardian Legend, which is actually known as Guardic Gaiden. As “Gaiden” tells you, this is a sidestory to Guardic, Compile’s Japan-only 1986 shoot ‘em up for the MSX home computer. Guardic itself isn’t standard for its genre: it’s a shoot ‘em up, yes, but the whole thing takes place within self-contained rooms and corridors, rather than a series of themed stages. You enter a room where you must defeat every enemy within it, at which point the exit will open, allowing you to proceed. You’ll fly down corridors and then choose another room to enter, which will lock and force another confrontation. The game includes 100 of these stages, but you don’t have to play them all: you just have to work your way to the conclusion one corridor decision and locked room at a time.

And Guardic is itself part of a trilogy, which wasn’t actually known as a trilogy to anyone besides Compile themselves until 1990, when its third and final entry released. That would be Blaster Burn, which was subtitled as Budruga Episode III. Blaster Burn is an episodic shoot ‘em up released through Compile’s Disc Station “magazine” starting in 1990. The power chips and kills collected in previous episodes could be used in future ones to level up your ship and upgrade its weapons and defenses, which is just a wildly ambitious concept to exist in 1990 on the MSX, but that’s just how this Budruga saga went. Guardic is the second entry in this trilogy, with Final Justice, a 1985 shoot ‘em up released for the MSX, the initial entry. Guardic Gaiden might “just” be a side story entry in this Compile series, but it certainly held up its end of the bargain as one that’s structured in an unconventional way.

While Guardic and Blaster Burn are both good games with concepts that make them more intriguing than that quality implies, The Guardian Legend is genuinely one of the best titles on the NES. That isn’t a universal opinion, but that has more to do with its status as a weirdo cult classic than anything. IGN ranked it number 87 in its 2009 top 100 for the NES, while Paste Magazine didn’t include it in theirs. Neither list is being mentioned to criticize them — Paste’s list, especially, is full of some other cult classic and lesser-known titles that I know of (and now own) in no small part because they were included within — but to make a point. I get the sense that the somewhat confused reception to The Guardian Legend when it initially released, in combination with a lack of sales and exposure for most people, plays a significant role in it just not being broadly discussed in the way I consider it, and somewhat easily forgotten or never considered in the first place. But it’s a true classic and an overlooked one, with that being the case both in 1989 when it released in North America all the way up to the present.

First impressions and all that, let’s start with the game’s cover. In North America, the cover art takes more than just a little cue from the 1985 film The Creature.

This isn’t new news, either: back when Hardcore Gaming 101 was blogging, there was an entire entry dedicated to The Guardian Legend’s regional differences in covers, and the inspirations and artists behind the wildly varying art. North America’s was easy enough to pin down, considering the above. Now, this art isn’t bad, but it doesn’t do a great job of selling you on what the game might be about. What could those eyes mean? Who do they belong to? At least with The Creature, you can make the assumption that those are the eyes of the titular creature. The choice of Broderbund to go in this direction for The Guardian Legend implies nothing about what’s inside the box, and if a game ever needed you to understand even a little bit what you were about to pick up, it’s The Guardian Legend.

Let’s look at the Japanese cover to see what I mean:

A tangle of cables and metal, forming together into something that is both machine and woman. The fusion of the inorganic with the organic is both the point of the piece and striking: is that hair coming out of her head, is it cables, or is there functionally no difference? It is, at the least, an intriguing image that makes you want to see what’s within, what this character’s role is. And, in fact, this is the Guardian the game speaks of: Miria is an “aerobot transformer” who can assume a “normal” bipedal, human-like form, but can also change her shape and function into that of a small-scale starfighter, which is what you control during the shoot ‘em up stages of The Guardian Legend.

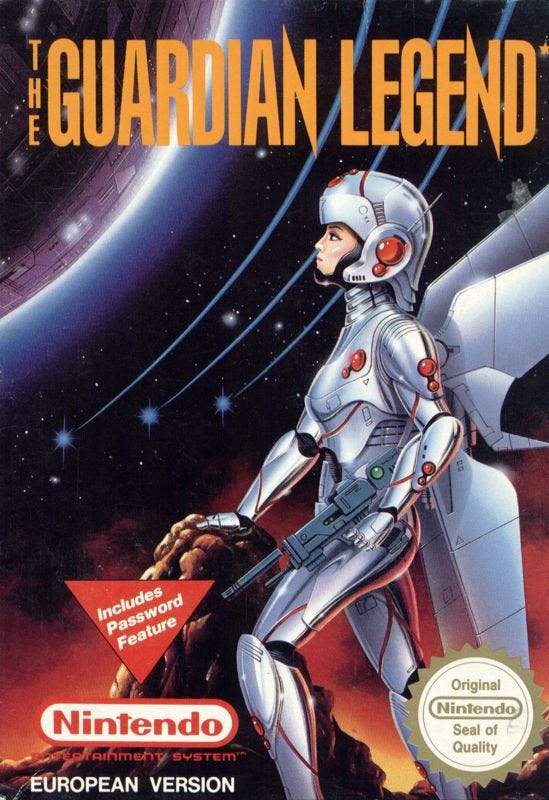

The European version of the game took a much different stylistic approach to showing Miria/The Guardian — it’s harder, both in its depiction of the metal that makes up the character’s body as well as in the way her face is designed to look, and it could maybe be confused more for a suit of armor and helmet rather than her body itself — but it’s at least more in line with what you can expect to find within, and the wings are even more prominent:

I cannot tell you what Broderbund was thinking here, other than that they wanted some kind of tie-in to existing media to draw attention. A woman who is also a transformer should have been far more of an attention getter than “hey, remember The Creature?” but as I was all of three years old in 1989, I can’t exactly speak to the climate and the potential prevalence of the anti-lady transformer community of the time.

Well, maybe a little. Playing through 2023’s excellent interactive documentary game re-release, The Making of Karateka, does make it pretty clear that the culture of the time was “Americanizing” more foreign elements as much as possible, which is how a game about a good karate master saving a woman from an evil karate master had so many blonde white people on the cover — as the notes contained within the game detail, that wasn’t always how developer Jordan Mechner saw the characters, but publisher notes and revisions over time brought them there. Broderbund, by the way, was the publisher for both Karateka and for The Guardian Legend, and they were far from alone in the trend of avoiding making it obvious these Japanese games came from Japan, which was, as you might know, not America. And 1980s America liked their transformers a little boxier and less feminine.

As for the The Guardian Legend itself: you play as Miria, on the seemingly synthetic solar object, Naju. It’s heading right for Earth, and unless it’s diverted or destroyed, they’re going to collide. Miria arrives and finds a message from who had been the sole survivor of Naju, explaining that there’s a self-destruct sequence, and that if someone is reading this message, than their mission to start it must have failed. It’s now up to Miria to find the keys needed to reach the self-destruct mechanism, and blow Naju up before it causes untold destruction in a collision with Earth.

To do this, Miria will need to traverse a large open-world that’s not so open when she gets there: everything is connected, a la Metroid, but when you start, it’s all locked up. As you explore the 11 different areas of Naju, however, you’ll discover that it’s all of a piece on one large map, with you able to backtrack or return to find whatever upgrades or items you had missed or saved for later along the way. Area 0, where you first discover the specifics of your mission, is basically a hub at the center of Naju, with the other Areas are connected either to that in one nook or another, or to another Area, like how you need to travel at least briefly through Area 6 to reach Area 7.

At the end of each Area is a Corridor, which you need to figure out the secret to opening by exploring wherever you can reach: sometimes the hint is in the same Area you’re trying to open the Corridor in, sometimes it’s elsewhere, like in a previously locked away portion of Area 0. The Corridor is where the shoot ‘em up sections are, and there is always at least one and sometimes two per Area. The gameplay is vastly different here than in the more action-adventure sections that lead you to the Corridor, but they’re also completely intertwined. More on that in a moment.

When you’re traveling through the Areas, you’re using Miria in her humanoid form. She has a blaster, as well as a slate of secondary weapons with limited ammunition. The secondary weapons consume chips with each use, which are also used as currency and a threshold for the power level of your primary weapon. In addition, each subweapon has a limited number of uses until you can refresh them by collecting certain items, like those that also refill your chip supply. You can’t just run around holding down both fire buttons at all times, basically, because doing so will cause you to (1) run out of shots for your subweapon and (2) leave you with a much weaker primary weapon until you can find replacement chips. The further you get into the game and the larger your store of both chips and secondary weapons go, the less of a problem this is, but early on you have very few chips to spare, and using them in any way will result in a very weak primary weapon against enemies that can take a beating even when you’re powered up.

There are 12 secondary weapons, with 11 of those being usable in Miria’s human form, and one exclusive to the Corridor stages. They work the same in both the action-adventure portions and the shoot ‘em up ones, though, the use cases might be separate, given the kinds of enemies you face in the two are dissimilar and require altered approaches. The forced vertical scrolling and screen-filling projectiles of the shooter levels are going to ask something different of you than a static room where you are moving in eight directions to avoid both enemies and their attacks while you fire on them.

How the two otherwise disparate sections of the game are intertwined, however, beyond even just the shared selection of secondary weapons, is their power. If you don’t have upgraded secondary weapons, or the higher defensive abilities that come from those upgrade items, stronger primary blasters, etc., the Corridors become nearly impossible. The Guardian Legend isn’t Zanac, with an adaptive AI system making the game more or less difficult based on your performance in it. The levels are the levels, and if you don’t look around for upgrades, make smart purchases in shops, and work to power yourself up and increase your health, then Miria isn’t going to last against enemies that will melt your health bar in an instant if you can’t both kill them and destroy what they’re trying to kill you with in the same shot. Similarly, your rewards at the end of these shoot ‘em up sections is not just the key you went into the Area to look for in the first place, but also upgrades, whether to your arsenal or your health or your power levels.

Each instance of a secondary weapon you find upgrades that weapon: it will end up costing you more in chips to use, but its power is both increased and its potential enhanced. So, the beam that you can fire behind you and to the sides while you shift away from foes, for instance, becomes a larger and more powerful beam capable of hitting more targets harder. The saber laser, which starts out as a short laser sword, becomes a much longer one that allows you to keep at least a little bit of space between you and the foe you’re brandishing it at. The wave attack increases its rate of fire significantly in addition to being stronger, which lets you cut through even more powerful enemy projectiles to save yourself from imminent death. Remember, too, that you can use your secondary and primary weapons at the same time, just like in many of Compile’s shoot ‘em ups like Zanac and Aleste. That’s a lot of firepower, but you’ll need it.

As for the base strength of your primary gun, you’ll find upgrades scattered about, as well as ones that increase the rate of fire. Changing the actual spread and size of your primary shot is a little more complicated, though, as that’s tied to your chip level: you need to find items that increase your maximum chip count in order to grow from a single shot to a double to a triple and so on, until you’ve got a killer rapid-fire wide array of shots with each pull of the trigger. The “Red Lander” items increase your chip count, up to 4,000: every few Red Landers, your shot will change form. However, if you spend your chips, either in shops or through secondary weapon usage, and the total drops below the threshold that gave you the upgrade, you’ll drop back to an old, less powerful shot. Temporarily, though, until you get your chip count back up. You start being able to have just three shots on screen at once, but when you max out, you’re firing four rows of shots with 16 bullets maximum. And as your last upgrade gets you to 4,000 chips, and the final threshold for dropping in weapon level is at 2,050 chips, you’ve got a lot of wiggle room to utilize secondary weapons once you do finally find all those upgrades.

There are also Blue Landers, which increase your total health by one point on a health bar. This just one way to increase your health, however, as the other is through your points scored. At 30,000 points, you get your first extension to your health bar, then another at 100,000, and 500,000, 1 million, then every million after that. You’ll want those Blue Landers, though, as it takes a long time to keep getting those levels after you finally hit 1 million: you’ll be most of the way through the game by the time you hit 1,000,000 on the counter, and while 2 million is likely, everything beyond that probably requires a whole lot of dying and retrying in Corridors, which have the highest concentration of scoring opportunities.

Those Landers, by the way, are Randar, Compile’s 1980s mascot who appeared in a number of their games. Randar was in one cave in every region of Golvellius, and here, he’s both an item (like in Super Aleste/Space Megaforce) and where you go to retrieve your latest password for continuing your game later. Or, at least, create a checkpoint, which you’ll return to when you die with all progress to that point intact, even your score slash/points. Randar is also the shopkeeper, either providing you with an upgrade to a weapon at a price, or giving you a choice of three different items, two of which will probably be less necessary than one more obvious option, but it all depends on what you’ve managed to acquire and not miss to that point in the game, too.

Some games from this era that attempted a larger, connected map can struggle with letting you know where you are within it. The Guardian Legend, though, has one massive grid of a map if you press Select, and while it doesn’t give you much information as to what connects where and is more a general guide of precisely where you are within Naju at any given time, it does include an axis system which makes remembering where you need to go to much easier. Let’s say you find a shop with an upgrade you can’t afford just yet, or a door to a Corridor you don’t know how to open. Instead of having to memorize the path back there — which might not be for a long time depending — you can just write down its coordinate location on the map and the area it’s in (say, Area 4, X15, Y20). Now you know to head that way, and doing so is easy enough, as the current coordinate of each block on the grid is shown right in your HUD along with health, score, and weapon information. It doesn’t tell you where to go: you’re still going around some maze-like areas and all that, and have to sort that out yourself. But you can at least know where you are within the maze at all times.

There were some reviewers who complained that the shoot ‘em up portions of The Guardian Legend were superior, and that this probably should have been the entire game. I disagree with that notion, especially given how excellent the game as a whole is: the shooter portions are great, yes, but they’re better because of how they work within the context of the larger game, which is in concert with the action-adventure sections that are also better because of their relationship to the STG bits. But, once you do complete The Guardian Legend — no small feat, as it’s a challenge even when powered up in its back end — you unlock a password for the “Corridor Rush,” mode, which is just the shoot ‘em up levels in sequence from the main game, without the exploratory parts.

It’s not quite the same, though, as you can probably suss out yourself, since the action-adventure portions and shoot ‘em up portions are so intertwined. In Corridor Rush mode, you still get upgrades to make Miria more powerful. The thing is that these upgrades are based entirely on your score performance in the previous chapter, so if you do a poor job of defeating enemies and scoring points, you’re probably not surviving this challenging shooter-only mode. Blaster Burn’s episodic upgrade format might have taken inspiration from The Guardian Legend’s Corridor Rush, or maybe, as Blaster Burn began as an abandoned MSX game before finally releasing a few years later, it’s Corridor Rush that took a little bit of a nod from Blaster Burn despite releasing first.

Compile’s soundtracks were often memorable, and often outstanding, too. The Guardian Legend’s is one of their finest efforts, with an intro theme as good as anything else on the NES. The game’s main theme plays off of it, but like with Metroid, it’s what comes before the song truly “starts” that helps make this one, thanks to the mood it manages to build.

Slower, more evocative, a thing of chiptune beauty. Then there are songs like the theme used for mino boss battles, which sounds like it belongs in an NES edition of F-Zero that never actually existed:

Or the track for the Crystal Sector Corridor…

…which makes me think a lot about Delta Spirit’s 2008 song “Trashcan,” even though Compile was “limited” to the sound tech of the NES hardware instead of a studio with all the instruments and producers a band could need to write such a song within it, and came out 20 years prior, to boot.

If the comp to an aughts-era indie/Americana band from California track featuring a piano and electric guitars didn’t tip you off, The Guardian Legend, which features a transforming robo-woman staving off cosmic destruction, has a varied soundtrack. It’s a fusion of elements and sounds that seem odd without context, which is fitting given the game itself is a blend of seemingly disparate elements brought together into something new that not just works, but works fantastically, despite the chances of it not coming together even a little bit existed. Just some great work by Masatomo Miyamoto and Takeshi Santo, some of the last to be done by the latter before his departure from Compile and the formation of Sting.

Graphically, The Guardian Legend is impressive as well. The sheer volume of things on screen, whether enemies or bullets or projectiles or explosions, stands out. Especially later in the game, when everything is amped up. The Corridor sections sometimes scroll by at speeds that surprise given the hardware, especially with how much is going on with all of the above as the screen scrolls by like that, and the action-adventure portions of the game are full of detailed backgrounds and large sprites — you can tell Miria has those wings shown in the European and Japanese cover art on-screen. The animation where she hopes into a Corridor and transforms is also wonderful and seamless; the whole game is a showcase for Compile’s mastery of the hardware they’d develop on.

None of it went to waste, of course, but sales were low, and while the game had and has its supporters, it’s nowhere near what it deserves in terms of wider recognition. The Guardian Legend is a weird game, but it’s also a highly ambitious and successful game that thrived with its genre-blending in a way modern games would be lauded and praised for. And it did all of that with masterfully intertwined systems, two engaging modes of play, and a killer soundtrack, too. Find out for yourself if you can find a way to do so.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.