Remembering Hudson Soft: A history of Hudson's caravans

From an innovative way to promote one company's games to a welcome feature in shoot-em-ups by anyone who wants to implement it.

Hudson Soft, founded in the 70s, did just about everything a studio and publisher could do in the video game industry before it was fully absorbed into Konami on March 1, 2012. For the next month here at Retro XP, the focus will be on the roles the studio played, the games they developed, the games they published, the consoles they were attached to, and the legacy they left behind. After all, someone has to remember them, since Konami doesn’t always seem to. Previous entries in the series can be found through this link.

If you’re familiar with shoot-em-ups, you’re likely also familiar with the “Caravan” game mode. It’s a score attack, basically, but not necessarily limited by how long you can survive as is often the case in a mode like that. Instead, it’s traditionally a two- or five-minute experience, and the goal is to score as many points as you can in the very short time allotted to you. Sometimes you’re just playing the first few minutes of the game, other times the mode has been built from the ground up specifically with pulling off high scores in mind — there are no hard and fast rules about this sort of thing, other than the fact that it’s a high-score run where the clock is ticking.

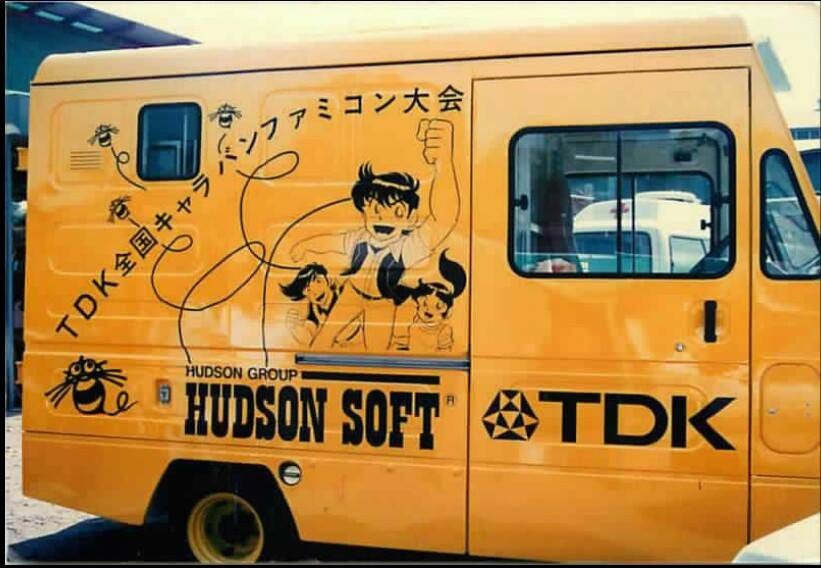

If you’ve ever wondered why the mode is named the way it is, the answer is Hudson Soft. The Hudson National Caravan, or the Hudson All-Japan Caravan Festival, was an annual summer event held by Hudson Soft from 1985 through 2000, with a brief revival in 2006, and even an online-specific version in 2008. Hudson wasn’t the only Japanese video game developer or publisher to put on a caravan event during this time period, no — Naxat, a rival of Hudson’s in this space, went so far as to publish games like Summer Carnival ‘92 Recca specifically for their own caravans — but they originated the successful concept.

The first-ever Hudson National Caravan was held to promote Star Force, which was actually a Tecmo (then known as Tehkan) arcade shmup with a worldwide release in 1984. Hudson ported it over to the Famicom and MSX in 1985, as ports to and from the Famicom were the thing they were doing the most of at that point in their history, and then used that version for the first Caravan festival. Star Force is a relatively simple vertical shooter all things considered — it, like so many vertical shooters of the time, was building on Namco’s 1982 arcade hit, Xevious — but it ended up having quite the legacy for itself, too, far beyond the little changes to the Xevious formula it introduced. And it’s all because of its inclusion as the first caravan game, the success of which would spawn further caravans, and also give Hudson a real-life mascot at a time before Bomberman would become their digital one.

Star Force is from a time where holding down a button to fire wasn’t by any means a given option for you in a shoot-em-up. Star Force had just one power-up, a rapid-fire one, but even that didn’t exactly bring your ship’s guns up to the kind of speed you might have wanted. And that’s where Toshiyuki Takahashi, aka Takahashi Meijin, came in. Takahashi Meijin — “Master Takahashi” — had experience as a programmer, but worked primarily in marketing and promotion for Hudson Soft. And it turns out he was damn good at shoot-em-ups, too, thanks to his ability to hit the fire button an absurd number of times per second — so fast that the rapid-fire power-up was actually slower for him than pressing the button again and again.

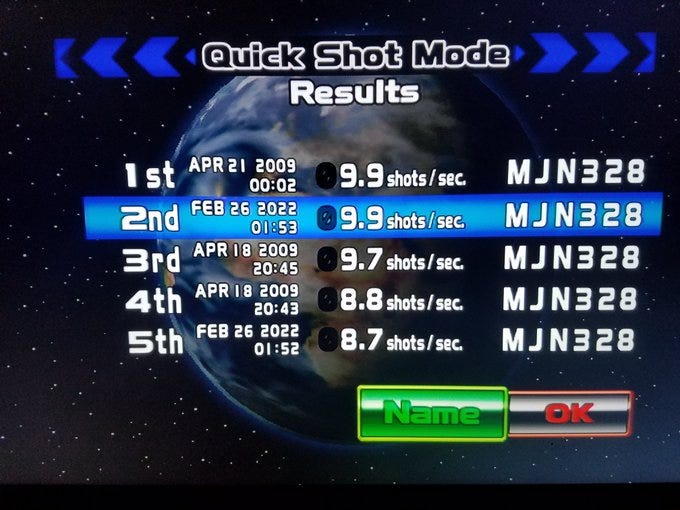

Takahashi’s ability to fire 16 times per second was and is ridiculous — I’ve personally topped out at 9.9 shots per second, both years and years ago and very recently, and cannot fathom how someone was able to do it six additional times in the same literal second — and Hudson utilized that skill to market their shmups and the Caravan festival with great success. Here, watch him in action playing Hudson’s Star Soldier — if any of you have played Star Soldier before, you know the ship’s cannons simply do not fire like that when you’re the one pressing the buttons:

No wonder they put this guy in his own video games — yes, this is the “Master Takahashi” of Adventure Island fame — and cartoons. What’s also funny is that Takahashi Meijin was actually capable of 17 shots per second at his peak, not 16, but he went with 16 because it was “more computer-like.” Can you imagine being able to do something so well that you have the choice of downplaying your skills simply because something lesser sounds better for marketing purposes, and it still leaves you in incomprehensibly elevated territory? Like Barry Bonds deciding he only needed to best Hank Aaron by one career home run instead of seven, just because 756 sounds and looks more memorable than 762.

And even decades later, when Hudson would revisit the concept of pressing the fire button as fast as humanly possible and make it an actual component of a Star Soldier release, Maijin was still capable of over 12 shots per second. I’m in awe of him, and so was everyone in the 80s who was interested in shoot-em-ups.

Maijin, by the way, shared his talents for pressing quickly with everyone else. According to Giant Bomb’s bio of him, his experience building controllers is what eventually led to the introduction of the turbo button — the original idea had been to reduce stress on his fingers since he was going around pressing as fast as possible as part of his literal job, but it expanded to become a component of controllers, including on Hudson’s own Turbografx-16, which featured multi-speed switches to enable turbo modes on the controller’s otherwise standard buttons.

Anyway, Hudson had staged the first successful Caravan Festival, driving their yellow van — you know, yellow, the color of their bee logo — packed with monitors and Star Force and Takahashi Meijin around to major cities in Japan to let people try their luck at setting a high score. Now what, though? Hudson had ported over Star Force and successfully marketed it in ‘85, but what were they going to do in 1986? Star Force was not their series, so they’d have to come up with their own and not rely on the chance that they’d find another game in the same vein to port in time for the next summer. And that’s where Star Soldier got its start.

Star Soldier games weren’t the only thing that Hudson used for their long-running Caravan festivals, but they were the centerpiece: the 1986, 1987, 1990, 1991, and 1992 All-Japan Festivals all included Star Soldier games, and 1989’s featured Gunhed, known as Blazing Lasers in North America, which actually served as a precursor for what Star Soldier would become in the following years on the Turbografx-16/PC Engine systems, much in the same way that Star Force informed the original Star Soldier.

The original Star Soldier was a Famicom/NES release, which Hudson published in Japan and Taxan would release in North America two years later. Like with Star Force, the ability to press the fire button extremely fast would be a major boost — Star Soldier is a game you want to play with the NES Advantage instead of a standard game controller if you can manage it. It’s certainly playable without an arcade stick and a base, but it’s going to be more difficult to fire 10 times per second or whatever if you’re also holding the controller in your hand, you know?

Star Soldier is fine and all, but the focus is very much on high scores more than anything else, so if that’s not your idea of a good time with a shoot-em-up — especially in an era before combos and score multipliers and such — then it will probably seem not only quaint, but a little unexciting, too. Hector ‘87, known as Starship Hector in North America, gave you a little bit more to do, since it pulled from the Xevious well and gave you targets to shoot at on the ground with a secondary weapon in addition to all of the ones flying around you, but it is also very much of its era. Fine by me, says a guy who has NES cartridges for both games, but not everyone’s proverbial cup of tea.

For 1989, Hudson didn’t go with an internally developed game, but instead, one they published after contracting a developer to make it for them. This game was Gunhed (in the North American Blazing Lazers, the ship is known as the Gunhed), and it was developed by Compile, a studio with real chops in the shmup space, on display in classics like Zanac and the Aleste series. MUSHA? Space Megaforce? Puyo Puyo? Well, sure, the last of those isn’t a shmup, but it is Compile, and it, like much of their shooter oeuvre, is a classic. Gunhed/Blazing Lazers introduced a much wider array of weaponry than had been previously available for Hudson’s caravan games, as that was like, Compile’s thing. A wide selection of beam types to choose from, that also continuously upgraded the more power-ups you grabbed, until you were covering most of the screen in your blazing lasers. This was a real change in direction from games that required you press the fire button so quickly that you become a Japanese celebrity, but it worked all the same. And it also changed the direction of the Star Soldier series, to boot.

As Compile would (gasp) begin working with Naxat after Gunhed — Seirei Senshi Spriggan was a PC Engine CD-ROM exclusive, yes, but it was also Naxat’s inaugural Summer Caravan title in their own festival — Hudson would bring in Kaneko to develop the first two of the Turbografx-16/PC Engine Star Soldier games: Super Star Soldier. Super Star Soldier would also be part of the Caravan Festivals, as Gunhed had been, and was very much in the same style as that game even without Compile doing the developing. The various weapon types that you upgrade over and over through the collection of orbs were back, and Super Star Soldier also featured built-in two- and five-minute caravan modes in the home release.

These modes were not just the normal single-player game but with a time limit, but designed exclusively with the idea of scoring lots and lots of points in mind. You not only would fire on enemies and enemy waves, but there were also tons of destructible objects, point orbs to collect, destructible squares worth bonus points, and an emphasis on just the one weapon: a standard dual cannon that could become more of a spread shot for covering a wider range if you picked up the upgrade. Dying would send you backwards in the stage and waste some time, which is the last thing you needed in a game mode where the clock was always ticking, and other than destroying as many objects as possible in the time allotted, you also needed to defeat bosses quickly in order to continue progressing to where more stuff to blow up was. It’s still somewhat simple compared to where things would end up on the caravan side, but there was more going on here than there used to be, which basically describes Compile’s whole time with the Star Soldier series.

The developer would shift once again for 1991’s entry, Final Soldier, with Now Production — developers of many Adventure Island titles for Hudson — taking the reins (funnily enough, Kaneko would, like Compile, go on to make a Caravan game for Naxat, though this entry, Nexzr ‘93, looks and plays an awful lot like Final Soldier instead of something new). This was a Japan-exclusive, likely because it feels a bit too much like the previous game for Hudson to spend any resources bringing it to the much less enthusiastic about shmups west. Though, there are some changes to how weapons work, and the checkpoint system is also different, as your next life begins where you died instead of with you being sent back to the beginning or the midpoint, so it’s not like they play exactly the same. And then there was the last Star Soldier game for some time, as well as the final shmup entry in Hudson’s initial run of Caravan Festival games: Soldier Blade.

There are two camps when it comes to Soldier Blade (and really, the PC Engine era of Star Soldier): it looks cool as heck and plays like a dream, or, there are better shmups to play on a system that is loaded with them. I think it’s fine to be part of both camps, because Soldier Blade, is cool as heck and plays like a dream, and there are better shmups to play on a system that is loaded with them. Two things can be true at the same time, we don’t need to fight about it, not in this era of inexpensive Virtual Console games and emulation. Hudson Soft, tired of contracting out to developers who would simply go on to make Summer Carnival games for Naxat, decided to make Soldier Blade themselves. It’s the best of the bunch in the series that they developed themselves, even if it predates Star Soldier: Vanishing Earth’s combo system that built on the original high-score foundation of the series while retaining much of the change that Compile et al built on top of it over the years.

Shoot-em-ups were still significant in Japan by the time Soldier Blade released in 1992, but the era of the fighting game was gaining steam, meaning, what was popular in arcades in the late-80s was not what was going to be popular in arcades going forward. Hudson’s focus shifted for a number of reasons, between the drop in popularity for shoot-em-ups that was only going to grow, and the growing popularity of their true forever mascot, Bomberman. In 1993 and 1994, Bomberman games were developed specifically for Hudson’s All-Japan Caravan Festivals: Hi-Ten Bomberman, which utilized a high-definition style screen for 10-player multiplayer madness, and its updated version, Hi-Ten Chara Bomb, which also featured characters from other Hudson games and series in addition to the classic Bomberman characters.

Bomberman would also be the focus in 1996 (Saturn Bomberman) and 1997 (Bomberman B-Daman), which makes sense given that, at that point, Hudson was no longer supporting any version of the PC Engine or Turbografx, and was focusing most of its energy on the consoles and handhelds of Nintendo, Sega, and Sony. Bomberman was their mascot, with games featuring him on every one of those systems, so the Caravan was now more about promoting Hudson and Bomberman — available on whatever systems you own! — than about any one specific game, a la Star Force, or about bringing eyeballs to Hudson’s exclusive titles, as featuring the PC Engine’s Star Soldier games had.

Caravans then became about card game tournaments, rather than video games. At least until 2006, when the video game version was revived to show off Bomberman Land Touch!, a Nintendo DS puzzle/party game that was also notable as the first of the Bomberlan Land games to be released outside of Japan. The actual last of the Caravan Festivals, though, was held online: Hudson released Star Soldier R for Nintendo’s digital WiiWare service in May of 2008. There was no single-player “normal” mode in Star Soldier R: the entire game was about Caravans, and caravan-related play.

There was a two-minute mode and a five-minute mode, as well as one just to measure how quickly you could press the fire button, like Takahashi Meijin. The game is very much a blend of basically all Star Soldier that came before it: it has the more basic weaponry of the original game and an emphasis on shooting quickly — you can choose between manual or automatic rapid-fire — but you can also move your ship at a speed of your choice and take down loads of destructible objects to boost your score, like in the PC Engine era. And the combo multipliers that are based on continually hitting objects and enemies to keep your score boosters active and growing from the Nintendo 64’s Star Soldier entry, Vanishing Earth, is here, too. It might only have the two caravan and Quick Shot modes, but if you’re into what the game is offering, you got a whole lot more out of it than “just” two- and five-minute experiences.

Especially if you participated in a slice of history, and attempted to log high scores in the month-long tournament that Hudson hosted through the power of online leaderboards. From May 27, 2008, through June 24 of the same year, Hudson logged every five-minute mode score in order to determine prizes for the top two competitors, and 10 others would be selected for additional prizes, as well. All you had to do was register on the tournament website page, and then start racking up points in the five-minute mode. More games should do things like this in the present. Hell, if Hudson were still around — they were fully absorbed by Konami less than three years after this — they might still be doing it.

Thankfully, the legacy of caravan modes lives on, even if the caravans themselves do not. Even at the time, you had competitors like Naxat hosting their own festivals, and in North America, companies like Blockbuster put on annual summer tournaments at their local stores using modified versions of hits like Donkey Kong Country, to promote themselves, the games, and to determine who the very best at collecting bananas was. In today’s world, though, the fascination with reviving classic games and the spread of online leaderboards in a very-connected video game world has made caravan modes as ever-present as they ever were. Hamster’s Arcade Archives series adds caravan modes to classic arcade games that never originally had one, and the addition is very welcome in an era where scores can be compared worldwide through online leaderboards, just like Star Soldier R was. It’s not just older games, either: even brand new releases like PlatinumGames’ Sol Cresta includes a caravan mode, as well as homages to the era of Compile and Star Soldier, like Raging Blasters. Hey, wait a second… Raging Blasters… Blazing Lasers. It’s all coming together for me now.

Hudson is no more. The All-Japan —and competitors like the Summer Carnival — festivals are also gone. The legacy of those Caravans live on, however — the concept outlived its originators. And not just when you play a caravan mode in a digital version of Hudson’s Star Soldier, games, either, but whenever Hamster or M2 or Platinum or whichever developer or publisher decides that a shoot-em-up would be improved by the inclusion of one. If you didn’t know about the festivals because you lived outside of Japan, the name never made any sense, but you still knew what the mode entailed when a game had it. And now, even as Hudson becomes more and more of a distant memory a decade on from Konami absorbing them then forgetting about nearly all of their franchises, caravans appear to be making a comeback — at least, in the last frontier Hudson was able to bring them to, anyway.

It’s not quite the return of Hudson, no, but it’s a way for part of their spirit to live on without it being at the whims of some finicky corporate decision making, and that’s worth something to me.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

Great article. Was a fan of Star Soldier and Bomberman as a kid. I remember seeing photos in game mags of Hi Ten and that massive HD CRT TV.