Remembering Hudson Soft: Adventure Island (series)

Born out of some nifty licensing workarounds for a port, Adventure Island ended up becoming one of Hudson's very own key franchises.

Hudson Soft, founded in the 70s, did just about everything a studio and publisher could do in the video game industry before it was fully absorbed into Konami on March 1, 2012. For the next month here at Retro XP, the focus will be on the roles the studio played, the games they developed, the games they published, the consoles they were attached to, and the legacy they left behind. After all, someone has to remember them, since Konami doesn’t always seem to. Previous entries in the series can be found through this link.

Adventure Island is a decidedly retro series, and one that hasn’t seen an actual rebirth or reboot to kickstart it into a modern era. The vast majority of the games in the franchise released between 1986 and 1994, with a budget, Japan-only GameCube remake of the original in 2003, and a brand new digital-only Wii release later in the decade, each of which had their issues that were very much of their time. It’s a little late for Adventure Island to get the kind of reintroduction that it deserves, in the sense that Hudson Soft is no longer with us so they can’t be the ones behind it. However, if the current holders of the Adventure Island IP, Konami, wanted to, there is still an opportunity to package together and re-release the games that already exist in anticipation of a very retro-style reboot that could land much better than previous, 3D-obsessed attempts.

Hell, Wonder Boy has already moved in that direction, with compilations and re-imaginings and now entirely new entries in the series, and you can’t get much more following in the footsteps of Wonder Boy than Adventure Island.

Hudson’s Adventure Island, released in 1986 in Japan and the following year in North America, is Wonder Boy. Sort of. Wonder Boy was a game developed by Westone Entertainment and released in arcades worldwide in the spring and summer of 1986. In the game, you play as the titular Wonder Boy, Book, who is a caveman out to rescue his girlfriend. He might be a caveman, but he has access to a skateboard. The platformer sees you trying to reach the end of the level before a quick-moving timer runs out: the timer can be refilled by collecting fruit, but watch out, as a single hit will kill you and force you to restart.

Wonder Boy was already running on Sega hardware — the arcade board it was developed for was 1983’s System 1, and the System 2 update to that board had graphical similarities to Sega’s home console, the Master System — so it’s not a surprise that Sega would handle publishing duties and get an exclusive deal in place to release Wonder Boy on consoles. This was the 80s, though, and workarounds to get popular games onto other systems could be found, even if there was an exclusive deal in place. Hudson wanted to get in on the Wonder Boy action with a Famicom/NES port, since they were familiar with that hardware and known very much for their port work at that time, but Westone (then known as Escape) didn’t just give Sega publishing rights to a home port, but had also sold the characters and series’ name to Sega as well. So, the two worked out a deal, in which Hudson got partial rights for the contents of the game itself, but not the name of it, or any of the characters within.

Hudson got the stages, basically, and could reuse the concepts of Wonder Boy exactly. And they did! Book (or Tom-Tom, which Sega’s international releases called the protagonist of Wonder Boy) got a new look and a new name. The protagonist was still rescuing a damsel in distress, but she was Princess Tina now instead of just Tina, love interest, and he was saving her from the clutches of the Evil Witch Doctor residing on Adventure Island in the South Pacific, instead of from the Dark King in a prehistoric past that also happens to have skateboards.

The games play very similarly, though, graphically, the original and Master System port of Wonder Boy are easily the superior games, thanks to the much brighter colorization of its console than that of the NES. You could certainly argue that Hudson’s soundtrack is the superior one, since Jun Chikuma’s NES work is some excellent, foundational chiptune music, but the point is that the games are very similar but each have their high points, too.

The one real separator might be that the controls are a little bit tighter and less reliant on pixel-perfect movement and jumps in Sega’s Wonder Boy port, but Hudson’s Adventure Island, as it was known outside of Japan, wasn’t exactly a problem in any of these areas, either. Either version has got that old-school difficulty that will turn away platforming fans without the patience to persevere — a difficulty high enough that Hudson would reduce it in a number of ways in future installments, while Westone would move away from the concepts entirely in their own series — but if you do happen to have the ability to fail and fail and fail and still want to try again, Hudson’s Adventure Island can be an enjoyable ride even now.

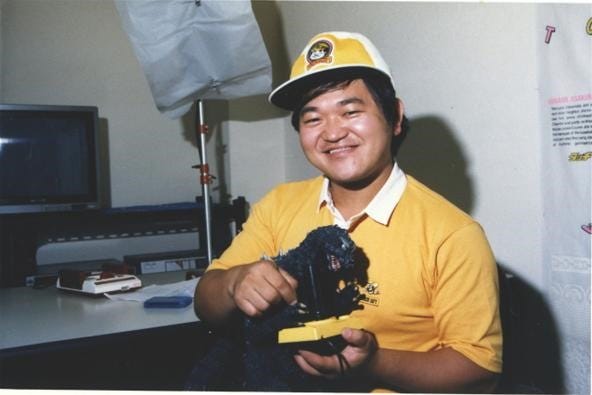

I mentioned that the protagonist’s name changed, too, and it did so in a way that definitely let Hudson get away with the idea that their version of Wonder Boy was legally distinct from Sega’s. In Japan, Hudson’s Adventure Island was known as Takahashi Meijin no Bōken Jima, or, Master Takahashi’s Adventure Island. The Takahashi in question was a real person — an employee of Hudson Soft, who was often used in the 80s as something of a mascot for the company in marketing and promotions. His real name was Toshiyuki Takahashi, but professionally he was known as Takahashi Meijin. And he likely has the most accurate 8-bit sprite portrayal of a real person in any video game from the 80s. Here he is…

…and here’s Master Takahashi’s sprite from Hudson’s Adventure Island, as well as modern promotional art for the WiiWare entry in the series:

The cheeks, the chin, the love of a baseball hat. And people think Hudson’s go at Wonder Boy is lacking the detail of the original!

Takahashi’s career at Hudson was one worth dissecting in more than one space, but for the purposes of Adventure Island, just know that he was a programmer who also worked in sales and in marketing, who ended up on television talking about Hudson products to an audience, was involved heavily in Hudson’s summer gaming caravans, and ended up being used as a mascot not just as the star of Adventure Island, but also for the caravans, and original animation. Hudson went all-in on Takahashi as a mascot at a time when their own primary mascot was still kind of an open question: remember, Bomberman hadn’t fully grabbed that title yet, given the relative lack of appearances for the character at that point in time, and this was in a pre-Bonk and pre-PC Engine world, too.

There are quite a few Adventure Island games, and they tend to play fairly similarly, though, there are exceptions and evolutions of the initial concept, too. Hudson’s Adventure Island played exactly like the game it was based off of, with a core concept that would keep throughout most of the series’ life: you have to balance moving as quickly as you can with moving safely through treacherous platforming stages, full of enemies, obstacles, and bottomless pits you can fall down. The timer is incessant, and it moves quickly: when it runs out, you die, but if you take any damage, you also die. Extra lives are earned through scoring points, which you get from defeating enemies and collecting items, usually fruit, though, there are sometimes some hidden bonus items that will net you more of a score, and from finding 1-up items on occasion as well.

Master Higgins (Master Wiggins in Europe, Master Takahashi in Japan) begins the game unarmed and only able to run and jump, but you will find upgrades inside of eggs. At first, you’ll find some throwing axes, which are low-powered but can be thrown quickly in succession in an arc, and you can upgrade to both a stronger and ranged weapon in the fireball, which can also destroy the rocks that the axes cannot, rocks that, if Master Higgins bumped into them, would deplete his timer bar by more than you would be happy about.

There are seven different worlds, each with four “rounds” within, and at the end of the fourth round is a boss who is pretty simple to beat, all things considered. Just don’t let them walk into you or swipe at you, and keep throwing axes or fireballs right at their face. Hudson loved making games where you can only hurt a guy by hitting him in the face.

The problem with the original Adventure Island is the same one that the original Super Mario Bros. has: too many of the later levels are simply a more difficult rearrangement of easier designs you played earlier. Now, neither game is a bad one for this — they’re both still very playable and fun, if you’ve got a taste for a certain age of platformers — but it’s the kind of thing that sticks out more now that much more varied and experimental games followed these originals.

And this is why the more enjoyable Adventure Island games are ones that came out after the first one: and as said, the first one is still a good time. Adventure Island II released on the NES in 1991, with development passed off to Now Production, a studio that has basically from the start worked on quite a few ports and sequels in established series. Adventure Island was one such series, with Now Production taking the development reins from Hudson for Adventure Island II, III, and IV on the NES/Famicom, as well as New Adventure Island on the Turbografx-16.

Now Production cut down the length of the levels themselves, making them a little less nail-biting in that regard, but difficulty still existed within those stages. There were also new additions to the gameplay, like ridable dinosaurs and items you could store in between stages for later use after dying — say you picked up a stone axe when you already had one, now it would go into an inventory and you could switch to that prior to a later stage, or use it after dying to avoid beginning a level unarmed. The game’s level design also opened up: to go back to the Super Mario Bros. comparison, this feels similar to the jump from SMB to the North American version of Super Mario Bros. 2, in that Now and Hudson made sure to broaden the locales and gameplay in order to progress the series and make it feel fresh, instead of releasing the Japanese version of Super Mario Bros. 2, which was basically just a hard mode of the original in a way that is often more frustrating than fun.

Adventure Island III continued with this trend, by introducing the ability for Master Higgins to crouch, adding a fifth dinosaur to count among his friends, new weapons (such as a boomerang), and expanding the item inventory as well. Though, the boomerang was just new to the NES Adventure Island series: it was in the Turbografx-16’s New Adventure Island, which was also developed by Now Production, and released in Japan a month before Adventure Island III did. More on that game later.

Adventure Island IV isn’t actually called that anywhere, as the final official release on the Famicom never did get an international release nor a Game Boy port like Adventure Island II and III, and therefore had the Japanese naming conventions of the series instead. This game removed the timer and added a health bar so multiple hits could be taken before Master Takahashi lost a life. It was more about exploring a world to find all of the hidden secrets and rooms and items, and taking your time to do so, which made it more like how Wonder Boy titles ended up being, but otherwise, it kept the trappings of the Adventure Island series. It is actually possible to play this game in North America without emulating it, but I do not suggest you do that: like many Hudson classics of the era, it received a Famicom series compilation release on the Game Boy Advance, but you will have to spend hundred of dollars to get one. So, you know, don’t do that.

With the NES era of Adventure Island wrapped up, let’s look at New Adventure Island, the only release in the series to show up on Hudson’s home console. It’s basically the ideal version of an Adventure Island title: it strips away some, but not all, of the additions to the series that the second and third NES titles made, such as the inventory and the dinosaurs, in order to focus much more on a streamlined and better designed version of the kind of game the original was. It’s not a reboot, by any means, but it could have been, considering how closely it hewed to the series’ original conventions while picking and choosing what parts of its successors could be repurposed here for the Turbografx audience’s first exclusive taste of the popular series.

The music of New Adventure Island is great, which is no small thing: the original Adventure Island was scored by 80s and 90s Hudson mainstay Jun Chikuma, as mentioned, while the first Super Nintendo entry in the series was composed by Yuzo Koshiro of Ys, ActRaiser, and Streets of Rage 2 fame. Neither of those supremely talented composers worked on New Adventure Island, but the energy they brought to their own Adventure Island projects and the music within certainly shaped the sound of the lone TG-16 experience, and in a positive way.

The thing that sticks out the most from New Adventure Island, however, is the sprite work. Master Higgins looks fantastic here, detailed in a way the NES simply could not. He’s larger, as are the enemies, the fruit, all of it. The backgrounds are significantly more detailed, parallax scrolling is employed, and the whole thing both looks and plays so smooth. If you’ve never played it before, then you should.

Super Adventure Island took a similar route to New Adventure Island, scaling back on things like the dinosaur allies, and trying to make a better looking and better sounding game than the original that would also play better, while still keeping much of that design intact. Reviewers were split on the game, with some feeling it had a little too much of that old-school identity left in a way that made it frustrating to play, and others enjoying that it was iterating on a concept they still enjoyed, and doing so in a bigger, brighter, bolder way. While this game was made by Produce instead of Now Production, it still felt like Adventure Island, which, again, depending on your perspective, was a good or a bad thing.

The final Adventure Island game for some time was Super Adventure Island II, and this would be developed by Make Software and released in October of 1994. Oddly enough, it was released in North America first, with Japan not seeing it until January of ‘95, a fact made even odder by its switch in gameplay. Adventure Island had now circled all the way back around to be just like Wonder Boy again, except, like the later Wonder Boy titles. You were still Master Higgins, and this was still an island adventure, but now it had more fantasy elements, and was focused on the kind of proto-Metroidvania action RPG elements of the Monster World era of Wonder Boy games. It’s not a bad game, not really, but it’s also kind of an unnecessary one, in that it doesn’t quite compare to the level that the classic Wonder Boy games from the same vein did. Between that and the success of New Adventure Island and Super Adventure Island in perfecting the original’s gameplay style, Hudson stopped focusing on this series at all.

There would be a 3D remake of the original Adventure Island for the GameCube in Japan, as part of a series Hudson did with their most popular franchises. It is a budget game, and it looks it. Trying to do polygonal versions of traditionally pixelated 2D characters did not work out for every studio that tried it, and when it did work, it was usually because a whole lot of time and money was invested in making it do so. That’s not to say it isn’t enjoyable to play, it’s just not enjoyable to look at, and you’re better served seeking out games like New Adventure Island or Super Adventure Island instead, if you’re looking for some kind of “Adventure Island, but with newer trappings” experience.

The last game in the series would come in 2009, with the WiiWare release of Adventure Island: The Beginning. Hudson took back the development duties themselves for the first time since the original, and once again tried to go back to the well that brought them the original. Like with the budget remake a generation before, this too was a 3D experience. The game was applauded by some for its classic gameplay — the notoriously fickle IGN of that era was happy enough with it, for instance — but the graphics and presentation were once again in question. This need to make everything 3D when it could have just been even more detailed and beautiful 2D sprites powered by the hardware of the day? It’s disappointing, but the industry’s need to force this square peg into a round hole wouldn’t dissipate until after Hudson was absorbed by Konami, and digital-only games were still too much of an experiment in 2009 to be given the kind of full budget and time an Adventure Island game needed in order to make the 3D transition work.

It’s been 13 years since that game, and a decade since Konami fully absorbed Hudson, and there hasn’t been a peep out of Adventure Island since. The Nintendo Switch Online service does not include any Adventure Island games, despite that both the NES and SNES are supported, and Konami has released not just their own original franchises on it (such as Gradius and TwinBee) but have also released Hudson’s Star Soldier on there as well. You can still buy Hudson’s Adventure Island and New Adventure Island on the Wii U Virtual Console, and the 3DS Virtual Console has both the NES and Game Boy editions of Adventure Island II — the latter of which is just known as Adventure Island since it’s the first Game Boy release in the series — but all of this is a limited selection even without considering that both shops will be shut down by around this time next year.

New Adventure Island was also included on the Turbografx-16 Mini console, so it hasn’t been completely forgotten about in the present, but Konami needs to step it up and make these games available again. They aren’t all winners, no, but plenty of them are worthwhile platforming experiences that make it pretty easy to see why they were well-regarded in their day. And losing them to time is something that just doesn’t need to happen, especially not in a retro-focused time where we keep revisiting the past again and again and rediscovering just how good things already were on the video game front decades ago.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.