Remembering Hudson Soft: It's been 10 years since Konami absorbed Hudson

Konami completed their purchase of Hudson Soft a decade ago this March: it's time to look back at a once-thriving studio that spent its life doing just about every industry job there is.

Hudson Soft, founded in the 70s, did just about everything a studio and publisher could do in the video game industry before it was fully absorbed into Konami on March 1, 2012. For the next month here at Retro XP, the focus will be on the roles the studio played, the games they developed, the games they published, the consoles they were attached to, and the legacy they left behind. After all, someone has to remember them, since Konami doesn’t always seem to. Previous entries in the series can be found through this link.

On March 1, 2012, Konami completed their purchase of Hudson Soft, and dissolved the long-time developer and publisher, absorbing the developers who stayed and the company’s IP into the larger Konami machine. The briefest explanation for how that has played out is to point out that over 70 Bomberman games released between 1983 and the 2012 acquisition: there have been just four since, with two of them being Android/iOS titles, and the other 2017’s console title Super Bomberman R, and its re-released 2020 form of Super Bomberman R Online that put it on Steam and Stadia, as well. That’s just one console Bomberman in the last decade, and even the last mobile one is already eight years old, which might as well be a century when talking about Android and iOS platforms. While Konami was never going to keep pace with the version of Hudson that was cranking out games featuring their mascot for multiple handhelds and multiple home consoles at once, the difference is still wild.

Bomberman, by the way, is the only franchise of Hudson’s that Konami has even really bothered with since the acquisition.

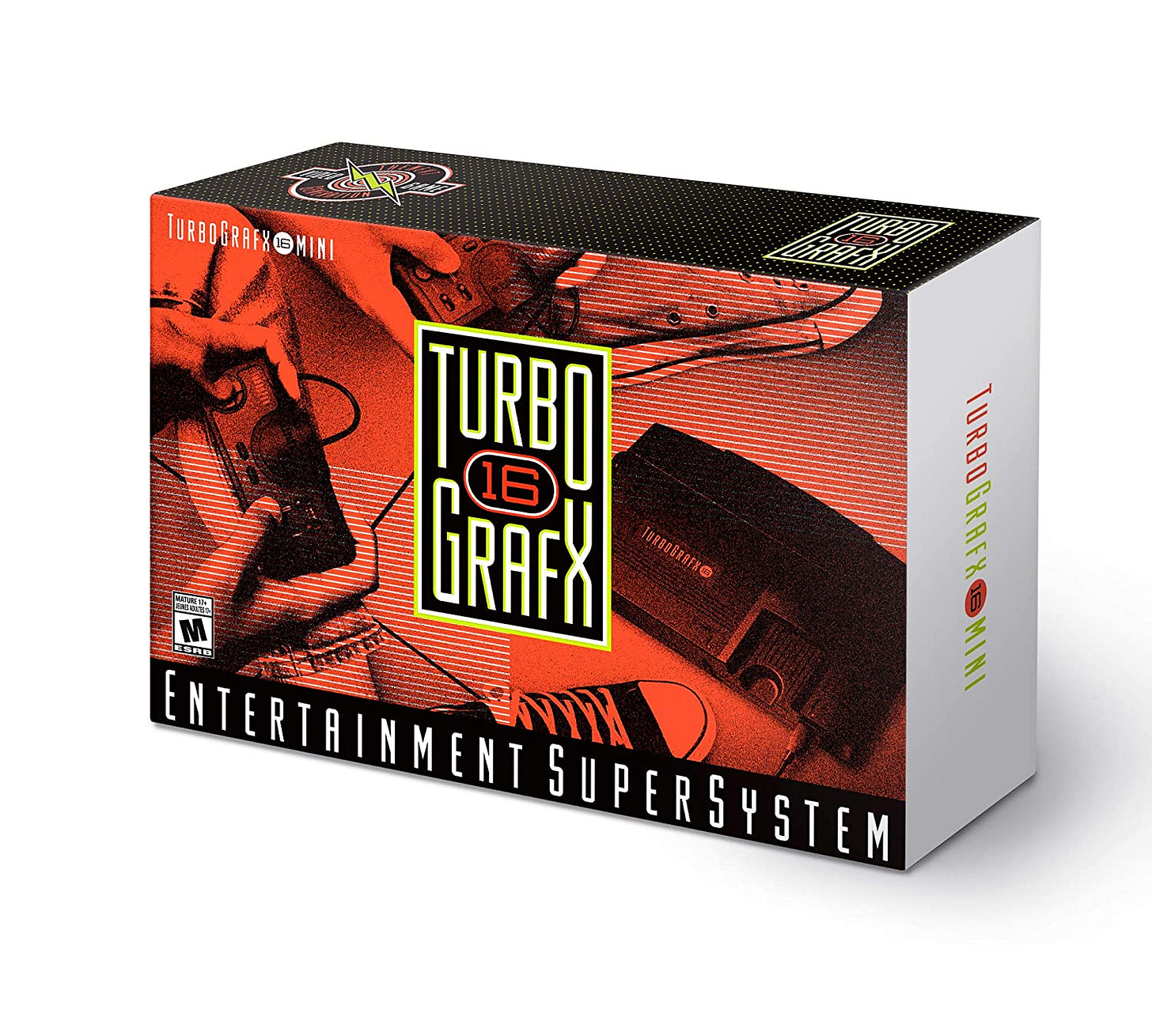

You (and Konami, apparently) might know Hudson best as the company that made Bomberman, of course, but they used to have their own console(s), and existed in times both before and after that era: they have more than just the one franchise, more than just the one mascot. With the Nintendo Wii Virtual Console already shut down and the closure of the Wii U shop imminent as well, one way of picking up both classic and late-life Hudson titles to play them in the present is going to vanish entirely. The Playstation Portable store is already nearly impossible to access, and the Playstation 3 and Vita stores are getting to that point, too, even if Sony stayed their outright execution for now: if you don’t go out and grab a Turbografx-16 Mini, available exclusively on Amazon from third-party sellers who have jacked up the price to three times its original MSRP, then you’re going to be stuck emulating entire chunks of their history if you want to experience them again or for the first time.

And that history is littered with some great games, a family of consoles that might not have made much of a splash in North America but was certainly popular in Japan (more so than Sega’s Mega Drive and its offshoots, and it wasn’t close, either), long-running partnerships with publishers like Nintendo and developers like Red Company, and innovations in genres like shoot-em-ups that continue to guide developers to this day.

Hudson was founded as an amateur radio shop and art photography center in 1973. They didn’t begin releasing software until 1978, when the business’ strategy changed to include personal computers. For the next five years their plan, like so many others in the industry, was quantity over quality, and that didn’t work: in 1983, they shifted gears once again, and began to focus on releasing fewer titles, but, in theory, better ones. The first Bomberman released in arcades in ‘83; it’s also the year that they signed a deal with Nintendo to port Famicom games to PC platforms such as the PC-8800, the X1, the MSX, and the ZS Spectrum. Porting popular Nintendo titles over was a whole lot more profitable for Hudson than radio equipment ever was, and it didn’t hurt that they were beginning to establish some of their long-running franchises at this time, too: not just Bomberman, but Lode Runner, Adventure Island, and Star Soldier all got their start in the mid-80s, too, before Hudson ever had a console of their own.

Hudson’s familiarity with the Famicom and porting is actually what led them to develop franchises such as Adventure Island and Star Soldier. Hudson was responsible for porting Tecmo’s Star Force to the Famicom and MSX, and while Tecmo (then Tehkan) released just the one sequel to this game on their own, Hudson ran with the concepts to create their own series: Star Soldier. Star Soldier games, in turn, became the initial centerpiece of their long-running caravan competitions, which were basically video game festivals and tournaments held in Japan: we’ll discuss caravans, their influence, and their legacy in more depth later on this month. As for Adventure Island — which we’ll also discuss in more detail later on — that was a nifty bit of work by Hudson to port Westone’s Wonder Boy to the Famicom, without infringing on the licensing deal Sega had already worked out with Westone to do so on the Master System. Adventure Island, too, became a long-running centerpiece franchise for Hudson.

Then came the era of the PC Engine and Turbografx-16. The first 16-bit system — sort of — and one whose eventual CD add-on showed off some exceptional growth in story telling, presentation, and the sound of video games of the era. It didn’t thrive in North America, as said before, but the PC Engine family of systems sold nearly 11 million consoles in Japan, compared to Sega’s 4.4 million for the Mega Drive and its add-ons. That 11 million figure might not sound like all that much if you’re used to global and modern sales totals, but Nintendo’s Super Famicom sold 17.2 million consoles in Japan: the PC Engine was a legitimate hit in its homeland.

Hudson would eventually leave the console market, however, and go back to working alongside other publishers and consoles. That’s where the Nintendo relationship North Americans are more familiar with began, between the Big N publishing various Bomberman titles on their platforms, and Hudson originating and continuing to develop the highly successful Mario Party series of games — games that, to this day, continue to be developed by former Hudson employees working for Nintendo’s internal studio, NDcube. Of course, Hudson wasn’t limited to just Nintendo platforms, even if that’s where they were at their most prolific: they had high-quality games on Playstation systems, Sega systems, and before the end came, even Xbox ones, too.

This era had its highs, but the transition to the HD era wasn’t kind to the longtime developer and publisher, in no small part because of how the sixth-generation of consoles began for them: with their bank collapsing, forcing Hudson to go public. Konami would buy enough of a stake in Hudson by 2005 that they were its parent company and the exclusive publisher of their Japanese games, and the number of shares they possessed continued to increase from there, with Konami having enough of them in 2011 to close down the American-based Hudson Entertainment in 2011, and then fully merge what was left of Hudson into their larger business in the spring of 2012. And now we’re here.

Hudson is much more than the story of a developer and publisher who ran into some financial trouble and were only allowed to continue to exist, for a time, because Konami swooped in and allowed it. They have some truly classic titles under their belts. They had a highly successful console in Japan, one that bested every system that Sega ever released there. They had one of the great composers of their time working on their key franchises in June Chikuma. Hudson might no longer exist, but their games still do, and so too does their legacy, even if Konami’s interest in keeping that alive runs hot and cold. Let’s spend the next month looking at all of this and more, as we remember a studio and publisher that was, at one time, a significant piece of a rejuvenated, thriving industry.

Between now and April 1, I’ll write a series of features looking at specific aspects of Hudson’s history, and in between, cover some key games and franchises that, nearly 40 years after Hudson found a viable development and publishing strategy, remain worth your time and attention.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.