Remembering Hudson Soft: The Turbografx-16/PC Engine

The early console wars were larger than Nintendo vs. Sega, even if it didn't seem that way in North America

Hudson Soft, founded in the 70s, did just about everything a studio and publisher could do in the video game industry before it was fully absorbed into Konami on March 1, 2012. For the next month here at Retro XP, the focus will be on the roles the studio played, the games they developed, the games they published, the consoles they were attached to, and the legacy they left behind. After all, someone has to remember them, since Konami doesn’t always seem to. Previous entries in the series can be found through this link.

Growing up in the United States, I had a pretty narrow view of the battle for supremacy between Nintendo and Sega. Sure, there were systems out there besides the Super Nintendo Entertainment System and the Sega Genesis, but those were clearly the heavy hitters. That’s not really how things worked, though, in large part because, as much as Americans might like to pretend otherwise, there is an entire world outside of those borders.

You probably needed to be outside of those borders in order to know much about what Hudson and NEC were up to in the age of the SNES and Genesis. The Turbografx-16, and its various add-ons and repackaged editions, sold just 2.6 million units in North America. It wasn’t just North America where it was clearly the third option, though: the Turbografx — known as the PC Engine outside of North America — never received a full European release, either, instead showing up in the United Kingdom, Spain, and France only. Sega and Nintendo were everywhere, with Sega picking up where it left off with the Master System in Europe and Brazil to get an edge on Nintendo in those spaces while also selling the most consoles in North America this time around, while Nintendo once again came away victorious in Japan, and finished in a strong second place in both North America and Europe — a strong enough second, and so far ahead in Japan, that they actually sold more consoles than Sega did worldwide.

The Turbografx-16 didn’t make enough of a dent in the North American or European markets to be easily found available for secondhand purchase decades later like the Genesis or SNES, but that had little to do with its game library or its quality. North America’s Turbografx library is lacking in comparison to the Japanese PC Engine library, sure, but it’s a system worth diving into today in a way those that lagged even further behind where Hudson and NEC’s joint venture did aren’t, outside of as a curio, primarily because the games are so good. We know this particular tree made a sound when it fell in the forest, even though North America wasn’t around to hear it. And hell, Japan heard it loud and clear: the PC Engine and its various add-ons and alternative releases sold nearly 11 million units in Japan, good for second place behind the Super Famicom (17.2 million) while crushing Sega’s Mega Drive and its add-ons (4.4 million).

The initial reason for support for the PC Engine, which released in 1987 in Japan, was due to its power. The system was the first 16-bit system, and the starting point for the fourth-generation of video game consoles. Now, the Turbografx-16 actually had an 8-bit CPU, not a 16-bit one, but the graphics processing unit was 16-bit, so you can criticize NEC and Hudson for marketing a bit of a fib, or you can just recognize that calling a console 16-bit when it was only sort of the case was more true than Sega’s claim of the Genesis powering its most impressive games with “blast processing” and move on. Especially since the 8-bit tech powering NEC’s little white box apparently ran faster than the SNES’s 16-bit CPU.

True 16-bit or no, it was undeniably a more impressive system on a technical level than Nintendo’s dominating Famicom, and people noticed. From its release in 1987 onward — according to what is either the truth or misinformation that has spread throughout various gaming outlets over the years — the PC Engine actually outsold the Famicom in Japan, only stepping down as the console leader there with the arrival of the Super Famicom in 1990. Given the PC Engine had a three-year head start on the Super Famicom, you can say it was much further behind in sales than the raw totals (17.1 million for the SFC, 10.8 million for the PCE) suggest. But it kept ahead of Sega’s Mega Drive in Japan the whole time, wrapped up its life a few years before the Super Famicom and Mega Drive did, and still finished with that strong chokehold on second place for the fourth console generation.

The PC Engine didn’t just come out of nowhere in Japan: there was already a market in place for a system like this. NEC was a tech giant in the 80s and 90s, one of Japan’s and the world’s most successful corporations in the space thanks to their work in semiconductors and personal computers. Their family of Japanese computer systems, like the PC-8801 and PC-9801, were huge for video games — a considerable amount of Nihon Falcom’s early output was developed for those PC systems, and they received loads of arcade ports and original titles that, in many cases, weren’t ported elsewhere, or localized for worldwide release.

The PC Engine was NEC’s attempt at joining up in the ever-growing console space, to get a share of that market in addition to their stake in PC gaming. They needed someone from the console world to partner up with, however, and that someone ended up being Hudson Soft. Hudson had actually wanted to enter the console space themselves, but, as is basically a theme for the company over the years, lacked the money to do so even if they had the ideas and the talent to make it work otherwise. NEC eventually figured out that Hudson was the perfect partner for them — they could produce the consoles and had the financial resources to invest in the kinds of specifications and technology Hudson wanted, and Hudson had the knowledge of the console world and talent to be the primary developer for a new venture.

Despite the strength of the partnership, cutting into Nintendo’s space wasn’t going to be easy. Due to licensing deals, competitors like Sega had already failed to make much room for themselves in the console realm in the mid-to-late 80s, especially not in North America or Japan: the Master System was hampered in part by the way Nintendo did business with third-party publishers during the reign of the Famicom. Licensing deals kept these publishers from releasing their games on other systems once they were on Nintendo’s own, which meant that the Master System couldn’t get their own, graphically enhanced versions of, say, Capcom classics like Mega Man on the Master System. Brazil and Europe were a different story, as Nintendo hadn’t made the same kind of inroads there as they had in the North American and Japanese markets. Basically, NEC and Hudson were kicking off the fourth-generation of consoles by hoping they had enough to go on between their combined reputations to make third-party studios choose their high-powered machine over Nintendo’s.

And the gambit worked, as companies like Konami and Namco and Taito, which all spent time developing for arcades in addition to consoles, saw the enhanced power of the PC Engine as a way to get more authentic arcade experiences into the living room. Sega, recognizing that the Master System was a relative bust but wanting to make money on re-releases all the same, granted NEC and Hudson permission to port their own arcade titles over to the PC Engine — if you have the Turbografx-16 Mini console and were wondering what the heck Fantasy Zone II was doing there when Sega had a perfectly good console at home to port it to, well, there’s your answer.

Falcom took some time to get on board, but once the PC Engine had some modifications under its belt — like the CD-ROM add-on — it wasn’t just classic and newer arcade experiences that the PC Engine was able to boast. It would now also had the best console versions of many of Falcom’s popular PC titles, which worked as an answer to Nintendo’s own relationships with Squaresoft and Enix. Sega, on the other hand, really only had their internal role-playing game development to lean on here, which, as good as those results were, can help explain part of why they didn’t catch on in Japan the same way the PC Engine did.

The PC Engine also had more going for it on the technical side than just the perks that come with being the first of a new generation of more powerful consoles. It had internal memory for saving games, which had not been done before: a whole two kilobytes of space! You laugh, but games were pretty small back at this time: World Court Tennis, for instance, took up all of 256 KB of space on its HuCard. the cartridge format the PC Engine utilized. Think of how relatively little space saves use up on your modern day consoles that measure storage by the half-terabyte, and suddenly, 2 KB of internal storage sounds impressive. The controllers came with Turbo switches, which meant you didn’t have to mash the fire button repeatedly in a shoot-em-up if you didn’t want to. And rather than having dedicated Turbo buttons to have to press, you could just set the Turbo switch to the speed you wanted, and press the standard buttons, which were now set to the speed you chose. The Turbografx/PC Engine also introduced a multitap to allow for far more players than the system was initially built for to play at once, and did so before any of the other systems managed to produce one, either.

The PC Engine received a CD-ROM add-on a couple of years before the Sega CD arrived on the scene, and it was the first such device of its kind. The way the PC Engine CD-ROM² worked, in its most basic form, is that it was a way to allow for much more storage for music, sound effects, and assets than the HuCard (or any existing cartridge of the time) allowed. This is how, for instance, Ys Books I & II could have such fantastic audio and voice-acted cutscenes despite being released in 1989. It’s why Lords of Thunder sounded like this in 1993, at the same time that you could rightfully complain that arcade ports to the Sega Genesis never quite sounded right because they weren’t initially developed with that specific sound chip’s capabilities in mind:

Red Book audio! That’s the standard format for compact discs, and it was a significant boost to how PC Engine games would sound, both with the music and with the addition of voice acting. At the same time that sound effects and music were interrupting each other as they fought for the limited space of the NES, Hudson and NEC were showing off what they could claim was the definitive version of an RPG classic, and much of that thanks to the format it was presented in.

And the add-ons wouldn’t stop with CDs, either. For one, there was a second version of the CD-ROM upgrade that enhanced the RAM (the Super CD-ROM), and in 1994, the Arcade Card memory expansion was released in Japan. The increased memory allowed the aging PC Engine to exceed the power of its younger rivals, the Super Famicom and Mega Drive, and while it didn’t close the gap with SNK’s high-powered Neo Geo, it narrowed it enough for ports of some of those games to make it to NEC’s and Hudson’s console. Just like Sega decided to port over their own arcade classics to the early version of the PC Engine due to its popularity and superiority over their own Master System, SNK ported games like Fatal Fury to the Arcade Card-enhanced PC Engine to get it in front of even more people in their homes.

Like with the N64 Memory Expansion Pak, there were games that required the Arcade Card to play, but also games that would just be enhanced with it around. The version of Ginga Fukei Densetsu Sapphire found on the Turbografx-16 Mini is a PC Engine CD-ROM title that requires the Arcade Card to play, and it’s easy to see why when you boot it up. As Hardcore Gaming 101 noted in their review:

Sapphire‘s biggest trick was convincing gamers that the game could render polygonal graphics in real time. This was believable, considering many enemies are made of simplistic, boxy polygonal models, with little or no texture maps, accompanied with extremely smooth animation. This isn’t the case though, as these graphics are prerendered sprites that take advantage of the massive RAM of the Arcade card. There are also tons of other cool graphical flourishes, especially the morphing effects, like the digitized holographic faces on the rooftop of the first stage, or the gargoyle that changes into enemy ships in the second. There are even scaling effects used in a few places. The animation of such frivolous details is often stunning.

It’s understandable that the hardware was being abandoned at this point — the Arcade Card released in the spring of 1994, seven years after the base version of the PC Engine — but it’s still undeniably impressive that NEC and Hudson had found ways to squeeze even more life out of it, and make sure that it held up graphically against newer consoles designed specifically for polygons and a transition from 2D to 3D gaming. If anything, it’s more evidence that the system and its add-ons were simply ahead of their time, as they all combined forces to allow something like Sapphire to exist in the first place. And with a smooth transition over time that had begun before the 80s ended, one that introduced the capability of higher-quality sound, for voice acting, and so on.

It all feels like more of a natural progression than Sega’s approach to just throwing a bunch of expensive ideas at the wall in the lead up to the release of the Saturn: Hudson and NEC weren’t splitting their userbase with (most of, but certainly not all of) their new iterations as much as they were offering new ways to experience games, and the technology was often impressive enough to get buy-in from third parties, in order to develop games they simply could not for the Super Famicom. The Sega CD was capable of similar things as far as Red Book audio and extra storage space for enhanced sounds and more assets goes, but the PC Engine CD-ROM had already successfully planted their flag in compact disc land, so there was little reason for the systems’ supporters to move off of their position to the one playing catch up.

If all of this was so cool, why don’t you hear more about it? Well, you probably do in Japan: not only did the various PC Engine systems sell more there, but there were just more games to choose from there, too. Just 45 Turbografx-CD games released in North America, but in Japan, there were 389 of them. That’s four games shy of the entire licensed Nintendo N64 library. The Sega Dreamcast had just 248 games in North America. The Sega CD add-on had 205 games in total. That 389 for the PC Engine CD-ROM isn’t a small number, especially not on top of all of the standard releases: even with the relative lack of support for the Turbografx compared to the PC Engine, there were still 686 Turbografx games to choose from (compared to the Super Nintendo’s 717 in North America). And many of them are damn good.

Retro Sanctuary wrote a top 100 for just Turbografx-16 games (as well as a few import-friendly PC Engine-exclusive titles) that’s full of good times, and even managed to squeeze a top 50 out of Turbografx-CD/import-friendly PC Engine CD games. You need to be a fan of shoot-em-ups and platformers to fully appreciate what the very arcade-friendly PC Engine family of systems had to offer, as that’s the particular era of arcade gaming that it thrived in, but if you’re into those kinds of games, the basic version of the system is just loaded. If you’re also into JRPGs and willing to wade through the emulation and fan translation waters in order to reach them? Then buddy, have I got the system for you.

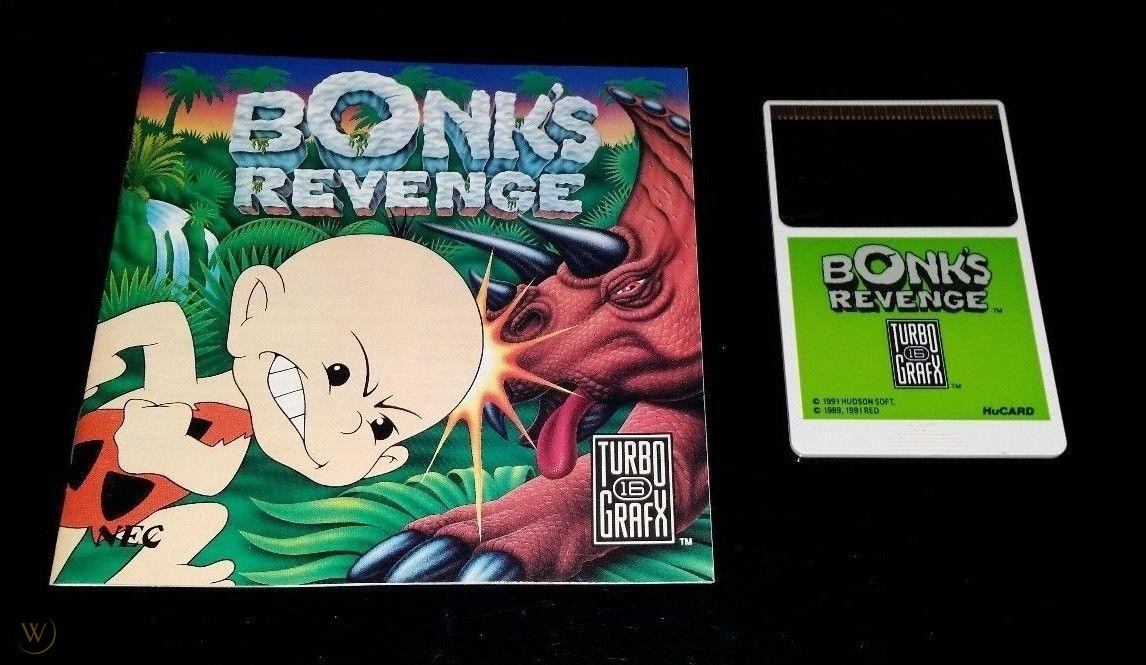

And this is all without even mentioning that Hudson killed it in their brief starring role as a first-party developer and publisher. The trio of Bonk games, Bomberman ‘93 and ‘94, the relationship with Nihon Falcom to get Ys and Dragon Slayer and Legend of Heroes games and more on their systems, excellent reprogrammed ports of arcade classics like R-Type, the Star Soldier games and Blazing Lazers, Dungeon Explorer, Lords of Thunder, Gate of Thunder, Sapphire, Nectaris/Military Madness, New Adventure Island, Air Zonk… Hudson was making great games for Nintendo’s dominant systems during this era, sure, but they kept plenty of greatness for themselves, too.

Not all of this broke through in North America, though, which is why you need to do a lot of the digging yourself these days. Things started off on the wrong foot with the international release of the PC Engine, which would be called the Turbografx-16 in North America. The pack-in game, Keith Courage in Alpha Zones, isn’t bad or anything, but it’s also based on a franchise North Americans didn’t necessarily know about, and wasn’t about to divert attention from what Nintendo was doing with Mario, either. Why wasn’t a Hudson-developed property given this space? Why did it take so long to come up with a better pack-in, to change course like Sega eventually would with the Genesis when they switched from a home port of arcade titleAltered Beast to Sonic the Hedgehog? For all of the innovations and correct calls Hudson and NEC made with the PC Engine in Japan, for all the support they got from third-party publishers to support the PC Engine over the Famicom, it just never picked up steam abroad, which ended up keeping those same publishers from ever being able to go fully all-in with their support of NEC and Hudson over the competition.

Which probably explains much of why NEC decided to go in such a completely different direction with the PC Engine’s successor, the PC-FX, which they wanted to focus basically exclusively on anime adaptations and pre-rendered animations. They couldn’t even come close to beating Nintendo and Sega abroad, and now Sony had entered the market, too, so it was time to zig while everyone zagged. NEC just decided to zig right into a wall found in an alley no one was ever walking through, is all. Hudson, as has been detailed elsewhere, just kept developing games for the competition while lending support it would be generous to describe as modest to the PC-FX.

The Turbografx never took off like the PC Engine did, no, and the whole thing didn’t stack up, worldwide sales-wise, with what Sega or Nintendo were doing, but it doesn’t have to be lost to time. Thanks to the release of a console mini that you could argue is the best on the market, and living in an age of emulation and fan translation where you can play just about anything from decades ago on devices of today, you can still experience what was on offer three decades ago. And you should, because the PC Engine has a far better library than you would imagine it to, considering its minimal international role in the console wars of its day.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

I have a turbo grafix 16 in my garage all boxed up eith a ton of games, and a arcade style joystick.

I'm missing the coaxial h ookup for the TV or I'd be playing that bitch!