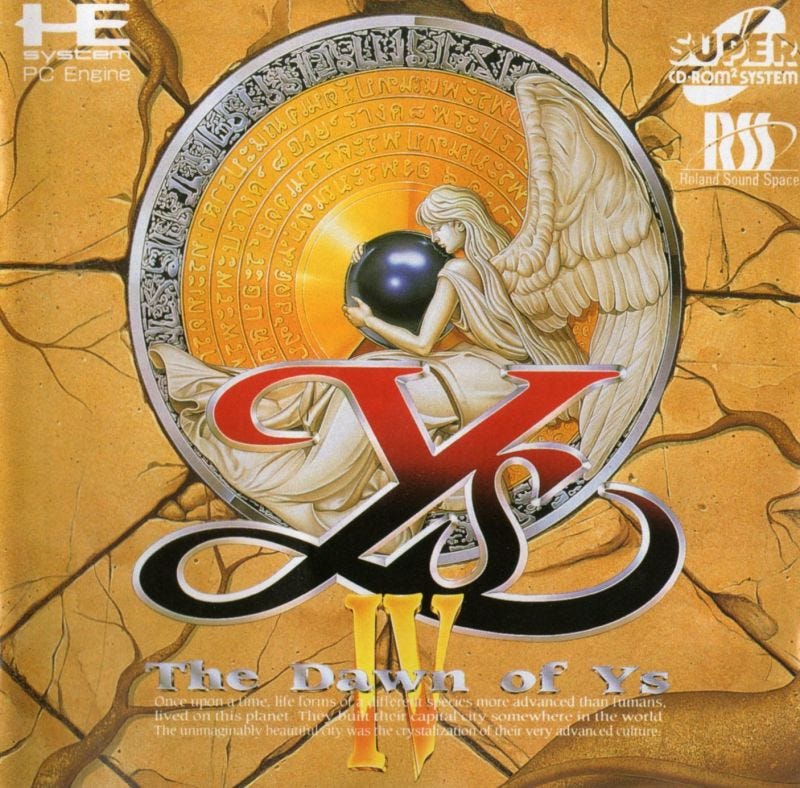

Remembering Hudson Soft: Ys IV: Dawn of Ys

Hudson developed one of the two Ys IV games from the ground up for their home system, the PC Engine CD-ROM, and there's an argument to be made that it's the best of classic Ys.

Hudson Soft, founded in the 70s, did just about everything a studio and publisher could do in the video game industry before it was fully absorbed into Konami on March 1, 2012. For the next month here at Retro XP, the focus will be on the roles the studio played, the games they developed, the games they published, the consoles they were attached to, and the legacy they left behind. After all, someone has to remember them, since Konami doesn’t always seem to. Previous entries in the series can be found through this link.

The very concept of Ys IV takes a bit of explaining, so let’s start at the beginning. Nihon Falcom developed and released Ys I: Ancient Ys Vanished, in 1987, with a team led by the likes of Masaya Hashimoto. Ys II: Ancient Ys Vanished — The Final Chapter would follow in 1988, and then a year after that, the two would be combined into one release for the PC Engine CD-ROM and (in 1990) the Turbografx-CD platforms, with a new and improved name: Ys Books I & II. Unlike the original releases of these games, though, the development was not handled by Falcom. No, Ys I & II were programmed for Hudson’s consoles by Alfa System, and published worldwide by Hudson Soft.

Alfa System and Hudson would also partner together to port Falcom’s Ys III: Wanderers from Ys to the Turbografx-CD in 1991, but that was the last of the Ys titles that were developed by the original team making those games at Falcom. Sometime after the release of Ys III, Hashimoto, as well as the scenario writer for the first three Ys games, Tomoyoshi Miyazaki, left Falcom and went on to form Quintet, known for titles such as ActRaiser, Terranigma, and Illusion of Gaia. So, when Hudson wanted another Ys game for the PC Engine CD after Wanderers from Ys, Falcom didn’t have one to give, as the always-small studio had just lost an immense amount of talent, and key developers who originated the franchise in question.

Falcom still took Hudson up on the idea, though, sketching out a scenario and songs for use in a game that Hudson would have to make themselves. Since Hudson wasn’t the only company programming Falcom’s Ys titles for home use, Falcom also reached out to Tonkin House, the SNES and Super Famicom developers for that version of Wanderers from Ys, to license out the plans a second time to a different audience. A pretty good deal for Falcom, considering that they didn’t have the development staff to make one Ys game, so instead they licensed outside studios to do the heavy lifting for them while they focused on projects that didn’t just lose their scenario writer and director instead.

Hudson’s version of Ys IV is titled Dawn of Ys, while Tonkin’s is Mask of the Sun. There are many differences between the two, but also plenty of similarities, as well, which makes sense as both studios were working off of the same starting point. Hudson, though, veered off from the script far more than Tonkin House did. As this transcribed interview from the time explains, this wasn’t done without Falcom’s approval, but it did still lead to the owners of the Ys franchise eventually choosing Mask of the Sun as the canon version of Ys IV. At least, until the remake that blended the two together, Memories of Celceta, ended up superseding both.

As far as the quality of the original Ys IV titles go, there is no contest between them. Dawn of Ys isn’t just the superior Ys IV, but it might also be the superior title among the classic Ys games, period. It combined the best elements of gameplay from Ys II and Ys III together — the addition of magic that gave our hero Adol ranged attack options, as well the addition of power-augmenting magical rings — while going back to the bump combat that Ys was known for before Wanderers from Ys brought us workable but dicier sword-swinging combat. And it went back to the overhead style of Ys I and II, as well, removing the sidescrolling elements that so angered Ys fans of the time period. I like Wanderers from Ys plenty, by the way, despite its faults, but it’s at or toward the bottom of the rankings for the Ys titles of the 80s and 90s, depending on how you feel about Ys V.

Mask of the Sun isn’t a bad game, either, but it’s frustrating in comparison to Dawn of Ys, and to Ys I & II, as well. The collision detection just isn’t right, and the game’s balance, both in terms of enemy difficulty and the experience they give you upon defeat, are both off, too. It doesn’t feel as carefully crafted in this sense as Falcom’s work with Ys, nor Hudson’s work replicating Ys for their own consoles. The bump combat is finicky: you need to be slightly off-center when attacking an enemy in order to have the initiative in bump combat. Come at them head on, even if you are equal to or exceeding their level and strength, and they might very well kill you, and fast. It’s more likely that you just have a lengthier than usual battle with the enemy, but let’s take this example from my own time with Mask of the Sun to consider how aggravating the worst-case scenarios can be.

Experience points received in Ys games are scaled to Adol’s level, so, enemies that were worth, let’s say, 40 experience per kill when you were level 10 will give you just a single point when you’re level 15 or 16. In these scenarios, enemies giving you just 1 XP are also enemies that are not worth chasing down since they give you slightly more than nothing in return, but you can still plow through them with bump combat if they happen to be in your path, because you’re just going to effortlessly tear through them, anyway. Not so in Mask of the Sun! Despite the best available equipment — like, literally just opened a chest to get the next sword after getting the latest armor and shield minutes before —and being leveled to the point that enemies were worth just a single experience point, they were still able to take Adol from full health to death almost instantaneously, because I did not come at them off-center, but instead head-on. Luckily, I had just saved, but I replicated this again a few times to see what happened, and the answer was always that they struck me first, and then again and again and again in such rapid succession that Adol’s health simply melted away before I could maneuver my way into turning the tide.

Without gaining any additional levels or changing my equipment, I then took down the next boss in the game in about 10 seconds, without having to heal Adol’s HP, despite taking damage a few times in the process. What? That is actual bad design, in the sense there is no consistent internal logic at work, and again, given the care of Falcom’s previous outings in the series, and contrasted with how Hudson handled their own version of Ys IV, Tonkin’s missteps stand out that much more. Part of the joy of playing Ys games is how they perpetually push you forward, and the bump mechanic makes that even easier to do. Unless you create a situation in which you are afraid to engage with even lowly enemies worth a single experience point, for fear they’re going to trap you against a wall and end you before you can react to their attack, anyway.

Dawn of Ys, meanwhile, actually built on the bump combat by adding diagonal movement, giving Adol far more freedom of movement both in maps and in combat — Dawn of Ys’ bump combat is seamless in a way Mask of the Sun’s is not, but if it hypothetically did have the latter’s issue with weak enemies being able to trap you, the diagonal movement would have made it far easier to escape those moments. Hudson also introduced some nifty new items to the series, like the Samson Shoes, which make Adol move at the slowest possible pace, but also allows him to defeat non-boss enemies in a single hit. It’s extremely funny to waltz into a new area, slightly underleveled, and then slooooowly walk around in a little circle for a minute wearing those shoes to just lay waste to everything and bring your experience up without feeling like you were grinding for levels by doing so. Highly recommended.

The bosses have ramped up in difficulty, with even the second one in the game being tougher to defeat than everything but the end bosses of the first two Ys titles. They require that you learn their patterns and figure out your timing in order to defeat them: this isn’t a situation where you can just run up to one and win without having to think much about what you’re doing (again, unlike some of how Mask of the Sun went down). While everything looks very much like Ys I & II on the Turbografx-CD stylistically, there is far more graphical detail in everything you look at here: it’s not “just” a redo of the past, even when regions from the older games are revisited. Hudson didn’t just go, “Hey, remember Ys?” when making this, though, they certainly did some of that, too. They aimed to build on what was already here, to improve the experience in a number of ways while introducing some newness to the series of their own, and they succeeded in that goal. It is the superior Ys, and for its tweaks and improvements to the series, arguably the superior of the classic-era Ys games, too.

Other than the quality of gameplay itself, the most significant difference between the two Ys IVs is in the story. They hit many of the same beats — the ancient, lost land of Celceta, the lost, winged race of the Eldeel, the conquests of the Romun empire in Ys’ mirror version of the actual world, etc. — but Dawn of Ys is designed as something of a bow with which they could tie up Adol’s PC Engine CD run. He returns to multiple locations from Ys I & II, sees characters from those games in more and in more meaningful ways than in Mask of the Sun’s cameos, and has the main thrust of the story tied into the history of the land of Ys itself in a way that neither of Mask of the Sun nor the eventual Memories of Celceta would.

And that makes a lot of sense for Hudson to do in order to (1) make their version of the game stand out from Tonkin’s and (2) create a scenario in which someone purchasing Dawn of Ys as their first-ever Ys might then go back to buy the other two that were available on Hudson’s console, and also published by them, too. It helps that none of it feels forced or unnecessary, either: it’s all just a seamless way to tie Adol’s and Hudson’s pasts together with their present, and it works for both parties.

And this distinction also makes Dawn of Ys worth playing in the present, too, as you can play Memories of Celceta to get a vastly improved version of Mask of the Sun and get on with your life, but in order to experience the very Hudson-specific iteration of Ys IV? Well, you’ll have to play that one, because while there are elements of it in Memories of Celceta, it was not the canon Ys IV, and therefore didn’t get nearly as much meaningful attention in the transition to the modern age.

As always, a moment needs to be taken to talk about the music of a Ys game. Having something as driving as “The Heat in the Blaze,” with this sound quality, on a console game in 1993 is not really something North American audiences were used to, mostly because the SNES and Sega Genesis just did not produce these kinds of sounds. The PC Engine CD-ROM did, though, thanks to its ability to use Red Book audio:

Tracks like “Temple of the Sun” are also incredible standouts that sound great even now, never mind by 1993’s standards:

And then there is “The Burning Sword,” which might be the most Final Fantasy track Falcom has composed, even though the song it reminds me of the most wouldn’t come out for another five months:

What an exceptional soundtrack, and while Falcom composed it, Hudson did have to arrange it for their system. It sounds better than what Tonkin managed on the Super Famicom, and I’m not sure all of that has to do with just the hardware in question. Hudson showed over the years that they understood the importance of music in games, too, and that fact is on display in Dawn of Ys.

Of course, to play Ys IV: Dawn of Ys will require you to emulate it. For one, it never released outside of Japan: Memories of Celceta was actually the first international release of any version of Ys IV. Second, it’s not just something you can go to a retro store and stumble upon, and even if you could, you’d need to have a working PC Engine CD to do it. Luckily, the game has been translated by fans (as has Mask of the Sun), and the localizers, Burnt Lasagna, even did English voice work for the game’s many voiced scenes, too. They did a phenomenal job with the text localization work: yes, the voice acting doesn’t sound as professional as what you’d hear in games released today, but it certainly does the trick, and fits very much with the aesthetic and era, too. I’ve played official voice acted releases from the time that don’t hold up as well, so you can’t ask for much more than that out of a labor of love.

It’s unsurprising that Hudson nailed their version of Ys IV so well. They had already shown an ability to port over Ys games to their systems, and porting other studios’ games was a thing they had shown aptitude for over the course of an entire decade before they had the chance to make Ys IV a reality when Falcom originally didn’t have any plans to go that route just yet. They had also already shown that they could make a from-the-ground-up Falcom title that felt like it belonged within their corner of the role-playing world, with Famicom/NES classic Faxanadu: Ys IV simply continued on a legacy that Hudson had already been building for itself. It might not have been the canon Ys IV, but as a representation of what Hudson was capable of as a developer and just a damn fine game in its own right? Dawn of Ys is certainly those things.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.