Retro spotlight: Catrap

The game seems, at first, like an overly simple puzzle platformer, but that quickly changes, and then changes again.

This column is “Retro spotlight,” which exists mostly so I can write about whatever game I feel like even if it doesn’t fit into one of the other topics you find in this newsletter. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

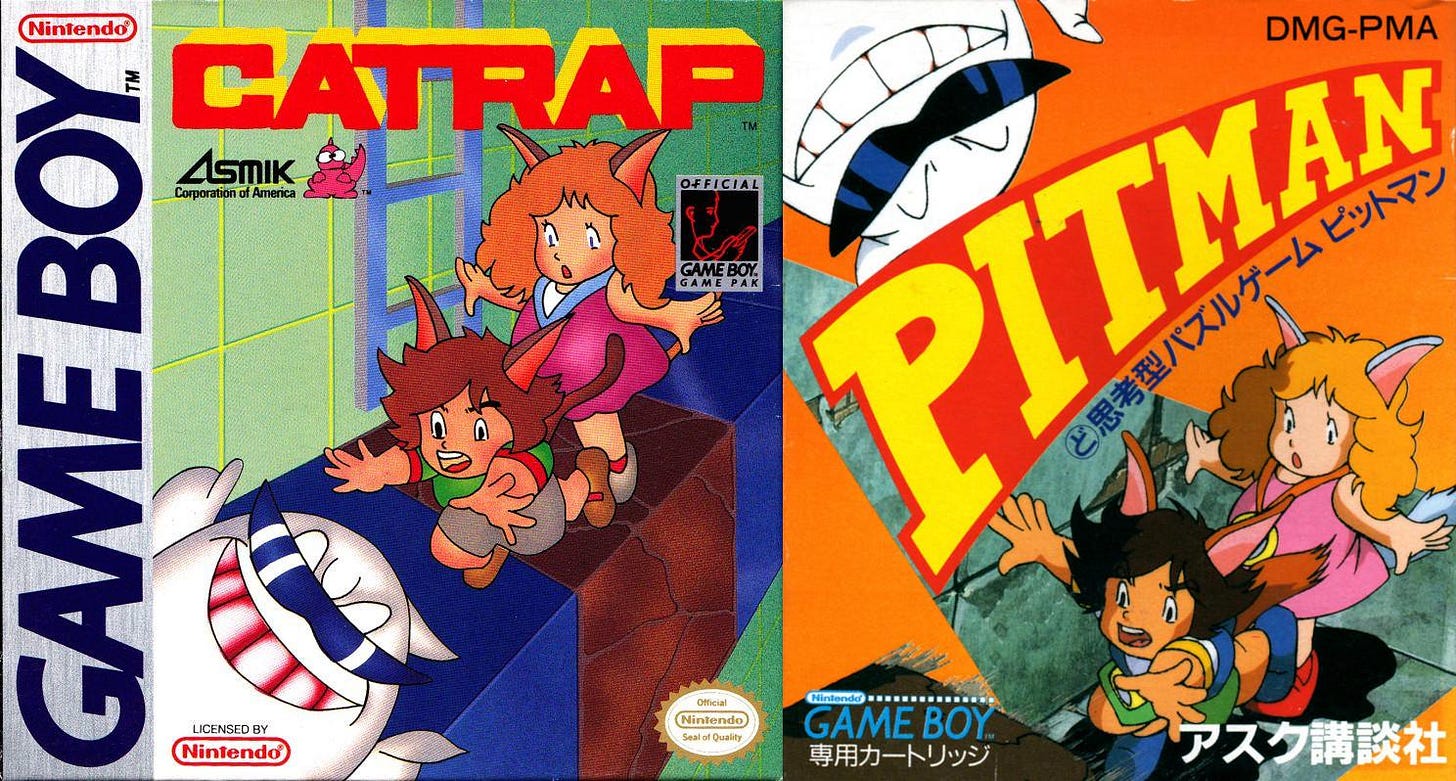

Catrap is not about rapping cats, but about trapped cats. Specifically, you are playing as a pair of anthropomorphic cats trapped inside of a 100-level labyrinth, and every monster within needs to be defeated in order to return the unnamed catboy and catgirl to being just people people. Almost every article you can find about Catrap talks about how it’s an obscure game, and it certainly is — there aren’t a whole lot of Asmik-published Game Boy games that turned into hits, you know, and it’s not like the good ones always released internationally, either. But Catrap, somehow in spite of all of that, received a release on the Nintendo 3DS’ Virtual Console back in 2011, which maybe didn’t move it out of the realm of the obscure, but certainly gave it attention it did not previously have. Its 3DS release is the reason I even knew it existed: reading about it came afterward.

Catrap is simple, in terms of the actions you can perform, its graphics, its sound. It is layered, complicated, and a supremely rewarding puzzle platformer, though, in terms of everything else. If you’re the kind of person who is into Donkey Kong ‘94 and its progressively more complicated puzzle platforming, then Catrap should be up your alley, too. That’s not to say that they play the same, because they sure do not: whereas Donkey Kong ‘94 is loaded with different jumps and moves for Mario to perform, and items and bonuses and such to collect, Catrap is focused on just one thing: you crashing into stuff at the right time, from the right direction.

You can crash into boulders, to move them one space at a time, or knock them off of a ledge. You can crash into the monsters in the labyrinth in order to defeat them — you won’t take any damage by touching them, as doing so simply initiates an animation of the monster getting punched in the face. You bump into soft earth that is holding up monsters, or boulders, or blocking your path, and it removes it from the stage. That’s it, and the directional pad lets you do all of this, as you can’t jump or run or anything else besides walk and crash and fall.

Well, there is one thing you can do, and that’s turn back time. The puzzles are designed to be completed in very specific ways, and you will spend your time trial and erroring your way through the stages in order to complete the various tasks that let you reach all of its monsters in the correct order. Since you can’t climb up or jump, you might discover the way to defeat an enemy or reach a location before you are actually supposed to do it: if there are monsters to defeat in an area that looks like you will not be able to leave once you fall into it or have boulders fall behind you, there's a decent chance that’s supposed to the monster you defeat last.

Instead of having to restart the stage when you accidentally do not leave that monster for last, or you start a chain reaction of boulders or get rid of some soft earth that turned out to be more load-bearing than you realized, or you go left after a boulder falls on your head instead of going right when left is going to trap you, you can press the A button to rewind time. It’s extremely helpful to be able to do this instead of just restarting from the beginning, and it lets you experiment without fear of needing to do everything over again, too, especially since there are no limitations to how often or how many times you can rewind.

Destructoid pointed out 12 years ago, before the game even released on the 3DS, that Catrap might very well be the first game to feature a mechanic like this — it’s even more likely considering that Catrap is actually just the Game Boy version of a 1985 Sharp MZ release, Pitman.* Think of how innovative everyone said Braid was, and then consider that Braid’s most definitive mechanic already existed within a game that released nearly decades before, and worked basically exactly the same way. That’s not to try to take Braid down a peg or anything: it’s meant to lift Catrap up, by pointing out its ambitions in 1985 and 1990 were still considered significant ambitions by the time Braid rolled around in 2008.

*For more specifically on the history of the Sharp MZ-700 version of the game, which I cannot speak on myself, Hardcore Gaming 101’s blog has you covered.

It’s this ability to rewind that allowed Catrap to make the puzzles as complicated and difficult as developer Kodansha did, too, so having the feature there is not just a matter of convenience. Knowing players would be free to experiment, to spend as much time on a particular level as possible using trial and error to progress, allowed them to make some serious head scratchers that required real thought. And believe me, you will find yourself stumped on more than one occasion, no matter how good you think you might be at this kind of game.

The first 15 stages of Catrap are almost so easy as to make you think there isn’t a whole lot happening or expected of you in the game. However, they are just tutorial stages that aren’t marked as such. They are showing you, in a simple manner, all of the kinds of maneuvers and planning you’ll need to make in order to complete the other 85 stages: once you exit the tutorial stages (which are not marked as such) and begin to play the normal ones, you will notice a significant uptick in difficulty, and much more experimentation on your end. (The above embedded video shows the introductory stages, as well as a few of the first ones where much more is expected of you.)

Or, another way to put it is that you might be wondering at first why the timer for each stage measures the time you spend in seconds, minutes, and hours, but get stuck long enough in a late-game stage, and the last of those will make a whole lot more sense. If you rewind, the clock keeps ticking up. If you restart the stage, the clock picks up from where you left it. If you hit the pause menu, the clock keeps going. Only if you exit the stage entirely does the clock stop. Since time is more about your personal accomplishment than anything, this isn’t a big deal, but the whole system should is basically setup to tell you that you’re not going to brute force your way through all of the game like you did the tutorial stages.

Consider, too, that, just as things became more complicated after the first 15 stages, yet another layer of depth is added on 15 stages after that. You no longer will be controlling just one of either of the cat people in order to solve a stage: you will be switching back and forth between the two of them, as this non-embeddable YouTube video shows, which means you will have to start placing one character in a place where they can benefit from the actions of the other character, in order to have boulders to walk across to reach ladders in order to get to more boulders or foes or whatever it is you need to complete the stage. Most of the game is played this way, bouncing back and forth between the two, so yes, it’s actually the first third of the game that serves as an education for the actual game you’re playing, not just those first 15 stages.

Luckily, you can play any of the game’s stages (save the final one) in any order. They’re all open to you, so if you end up stuck on a particular stage you want to try to solve later, you can exit and pick a different one. The final stage won’t unlock until you’ve completed all of the others, however, so if you want to actually get 100 percent completion, you’ll eventually need to go back to the levels that stumped you. This was a great decision, though, to not force you to stick with a puzzle that’s giving you trouble and allow access to the entire rest of the game from the jump. Like with the rewind mechanic, it’s a decision that was well ahead of its time.

Catrap isn’t perfect — that there are just two songs in the game, one for your catboy and one for your catgirl, could begin to get annoying even if the music is catchy. It’s also not a graphical masterpiece by any means, even for the Game Boy. Those little presentation issues aside, though, there is so much more depth and complexity here than I thought existed in any Game Boy puzzler, so despite my confusion about how this relatively obscure title ended up being one of the few released on the 3DS Virtual Console service, it also makes all kinds of sense that space was reserved for this particular gem. If you have a 3DS, you can get Catrap for just $2.99, which is a far better option than spending around $40 for an original cartridge of the game on Ebay. If you have to emulate it for lack of a 3DS, though, you should: it might look simple and start out that way in its gameplay, too, but it’s got the kind of depth and complexity to it that’d make it a critical darling today, if only it got a modern remaster or a release on something a little bigger than the Game Boy corner of the 3DS’ Virtual Console service.

Maybe write a couple more songs for that hypothetical remaster, though.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.