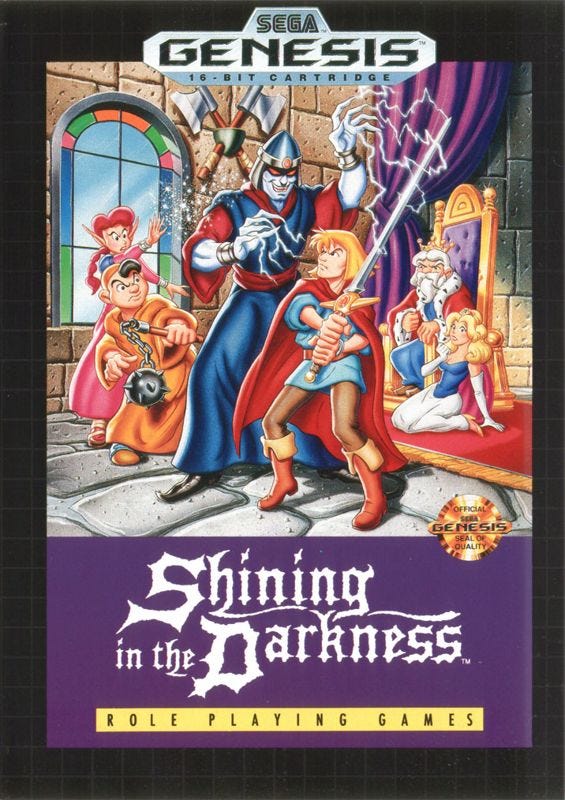

Retro spotlight: Shining in the Darkness

The actual first game in the Shining series was a first-person dungeon crawler filled with budget-conscious design decisions.

This column is “Retro spotlight,” which exists mostly so I can write about whatever game I feel like even if it doesn’t fit into one of the other topics you find in this newsletter. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

The Shining series was never a stranger to genre-hopping, especially after Camelot packed their bags and left development of it behind, but it got its start early there. Shining Force isn’t numbered as such, but it’s the second game in the series — the lack of number is because it’s the first Shining Force game. The actual first Shining title was released in 1991 in not just Japan, but also North America and PAL territories. That level of commitment to getting it out the door in a hurry was a bit surprising, considering how little Sega supported the game in its actual development.

Climax Entertainment, which was founded by Hiroyuki Takahashi after he left Enix in 1990, was responsible for the development of Shining in the Darkness. Shortly after the game’s release in Japan, Takahashi would co-found Sonic! Software Planning, which was primarily funded with investments from Sega, and they would eventually take over full development of the Shining titles from Climax, given the series was Takahashi’s responsibility in the first place. Never was this more the case than with Shining in the Darkness, however, which was made mostly by Takahashi himself wherever possible since the budget for the title was so small that he couldn’t afford to put more staff on it.

As Takahashi put it in an interview with GamesTM back in 2009: “Because we were on such a tight budget, apart from the programming and graphics, I did nearly all of the work on Shining In The Darkness.” The game was also composed by someone else — Masahiko Yoshimura — but you get the idea. Takahashi produced, wrote, and came up with the actual design and concepts for the game, and did much of the latter while still working with Enix — the programmer who built the first-person design of Shining in the Darkness, Yasuhiro Taguchi, was a freelancer whom Takahashi saw the work of while at Enix. That work? A first-person 3D dungeon crawler:

“When I was working as a producer at Enix,” Takahashi says, “I remember seeing a 3D dungeon game brought in by a freelance game creator. I was very impressed. I thought that if he was in charge of programming we’d definitely be able to make something special, and so I started to plan. That game creator was Taguchi, who is still our main programmer today…”

And so, a new studio was born, with a game already in mind.

While Takahashi’s design choice came well before the talk of financing for the game, it inevitably worked out well for the budget that Climax had to work with. From that same issue of GamesTM: “Sega gave Takahashi’s team the bare minimum funding offered to out-of-house developers. Shining In The Darkness was a success, but apparently not enough to merit a raise for the development of Shining Force; and although Shining Force was a hit, there was still no raise forthcoming when it came time for a sequel to be built.”

This was not an open world with sprites traveling around, but a first-person game taking place in a labyrinth. You traveled on a map — a small one, with few places of interest on it — and there was the one castle and the one town. You don’t walk around the town, but instead scroll a piece of background art with some points of interest on it, and you can hop into a shop, or tavern, etc. this way, where you once again get a single screen of art that either has some characters in it or does not. It’s all as little asset use as possible, and this is also how you end up seeing a number of palette-swapped enemy sprites early on.

Battles take place where you stand within the labyrinth, not in a separate space, and the number of different backgrounds — truly different, not just more palette swaps of walls — is minimal for a game as long as Shining in the Darkness, which will take you a couple dozen hours to complete. Animation is at a minimum, the soundtrack has 28 tracks but a great number of them are short jingles — the total soundtrack time comes in at about 32 minutes, and that figure includes quite a bit of looping to get there. Climax made the minimum amount of art they had to make to build a labyrinth and populate it with enemies, and they called it a day. It’s the kind of decision that wouldn’t have been made if the budget had been more significant, but it wasn’t, so it’s how they rolled.

None of this is a criticism of Shining in the Darkness, by the way. There might not be a ton of music, but what’s there both works and is great, and very much fits what would become the Shining sound during this era. The art might involve a ton of palette-swapping whenever possible, but the designs already look like the kind of people and creatures that Shining games would come to be known for. They absolutely nailed making the kind of game where you’ve got one huge labyrinth to get through, just floors and floors of maze and dead ends and battles (and more battles) and hidden items and traps and progressively stronger monsters and the need for ways to escape certain doom when you have to, or else. It’s just worth recognizing that the game is the way it is because Sega was willing to give the green light to an RPG that wasn’t in the style of Dragon Quest or Final Fantasy, but not willing to support it beyond the minimum budget they gave to third-party developers for games they planned to publish. Which was a trend that continued even when development primarily moved to Sonic! Software Planning, which was a subsidiary of Sega. No wonder Takahashi ended up moving over to Camelot Software Planning, which his brother Shugo had founded, when given the opportunity.

Anyway. Shining in the Darkness involves a missing father, and the son who sets out to find him. You get to name this son, and while you’re looking for dad, you’re also seeking out the lost princess of the kingdom of Thornwood. You’ll find a couple of companions on your way — the priest-in-training Milo, and the elf mage Pyra, as well as some temporary assists from other warriors in the labyrinth. (Pyra would also appear as a playable character in the Dreamcast game TimeStalkers, which featured a number of Climax characters from other titles.) The story doesn’t play a major role here, other than to push you toward the labyrinth and the gameplay within, but that’s also all that’s needed to make the game work. It does end up connecting with other Shining games later on, but due to the various localization changes that end up impacting who villains are or what time frame you’re working in and all of that, you don’t really need to worry about all of that so much. You can, if you want, but for as fun as the Shining games are, it’s not like there’s a diehard community of lore keepers out there. They were never made for that sort of thing: they were made for fighting fun battles, and Shining in the Darkness lets you do that, dungeon-crawler style.

Just like Shining Force is an easier strategy RPG, Shining in the Darkness is much more welcoming to genre newcomers than the games that influenced it. Which, hey, so was Dragon Quest — that was a large part of the appeal of the series in the first place! If you’re looking for a difficult first-person dungeon crawler, Shining in the Darkness is not that, but if you just want a quality one to play, Climax has got you covered there. You use melee attacks, spells, and items to get through each floor of the labyrinth. You’ll fight a whole bunch of turn-based battles, but so long as you fight regularly and keep upgrading your gear when possible, you shouldn’t have too much trouble: if you’re constantly running away, or not exploring and just looking for the exit, or forgetting to go and buy new equipment when the money is there, you’ll struggle. But you’re also not engaging with the game when you do that, so, of course you will.

While the series would shift over to tactical RPGs for a bit, it would return to the first-person dungeon crawler setup before too long. Shining the Holy Ark, released on the Sega Saturn in 1997, still had to contend with the budget issues of its predecessor — Sega was giving Sonic! and Camelot half of the funds they’d provide to other developers of Sega’s “main” series, per Takahashi’s interview with GamesTM. Despite this, it not only returned to the first-person view, but Shining the Holy Ark rendered the game in polygons as well as sprites. Climax was out of the mix at this point, with Sonic! and Camelot handling development duties, and the goal, per Takahashi, was to create a darker, more mature storyline, with the idea being that Sega Saturn owners were all older and more mature than Genesis and Mega Drive owners had been.

In addition to the budget problem, originally, there had been no plans to localize Shining the Holy Ark to release it outside of Japan. Again, it’s pretty easy to see how Takahashi ended up ready to leave Sega behind, even if it meant heading to Nintendo at a time when their future was also becoming uncertain given the rise of Sony’s Playstation.

Sega has, in its post-console manufacturer days, seemingly come to appreciate Shining games in a way that they maybe did not when they were still in that world. Shining in the Darkness is regularly available to play in the present — it received a Virtual Console release in 2007 (which is where, on a personal note, I was first introduced to it), and has been included in both Sonic’s Ultimate Genesis Collection for the Playstation 3 and Xbox 360, as well as the Sega Genesis Classics collection that was recently delisted from the Xbox, Playstation, Switch, and Steam storefronts. Shining in the Darkness was included in the Sega Genesis Mini 2, and, while it isn’t on Nintendo Switch Online at the moment, one imagines it’ll get there eventually.

It will probably also be included in whatever ends up replacing the Sega Genesis Collection, which was delisted, yes, but was also released for Xbox One and Playstation 4 — its availability on the Playstation 5 and Series S|X had more to do with backwards-compatibility than anything else, so there might be something new using different emulation, or produced by different developers, set to replace it at some point in the near future. We’ll see, of course, but it would be a shame to lose easy access to something like Shining in the Darkness, which so clearly set out the look and feel of the Shining series even at such an early juncture, even with so little investment or support from Sega present.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.