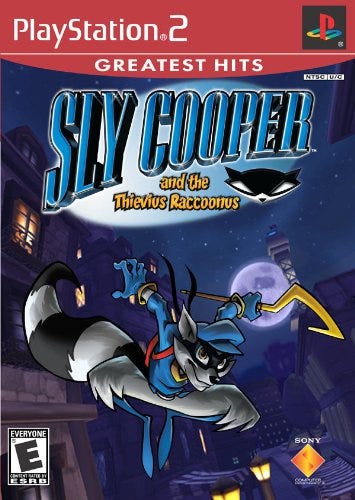

Retro spotlight: Sly Cooper and the Thievius Raccoonus

Sly's first outing still holds up in a number of enjoyable ways.

This column is “Retro spotlight,” which exists mostly so I can write about whatever game I feel like even if it doesn’t fit into one of the other topics you find in this newsletter. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Maybe it doesn’t feel to some of you like the Sly Cooper series is old enough to deserve the retro treatment, but it’s already been nine years just since the last new entry in the series, which was also three Playstations ago. The collection containing HD editions of the Sly Cooper PS2 trilogy? That first came out in 2011, before the Playstation Vita — which the collection also eventually released on — existed. (Sony, by the way, stopped producing games for the Vita in 2015.) Sucker Punch, the originator of Sly Cooper, last worked on the series in 2005: in the years since, they developed three Infamous games, two major Infamous expansions, and Ghost of Tsushima. The original Sly Cooper, the subject of today? That was Sucker Punch’s second-ever game, with their first, Rocket: Robot on Wheels, releasing on the Nintendo 64 three years prior.

If all this math is right, Sly Cooper and the Thievius Raccoonus released 20 years ago. Sony should probably bring back Sly Cooper, is one way of looking at things. And if it’s old enough to say that about it, it’s certainly old enough to get this particular spotlight.

Anyway, now that we all feel either very old or very young, depending, let’s talk Sly. That’s who you play as: a raccoon who has been orphaned due to the murder of his family by an unknown organization, whose goal in life is to get revenge for said murder and recover the pages of the Thievius Raccoonus, which is basically the century-spanning lifes’ work of his ancestors. Contained within are the secrets to thievery that have allowed them to be the thieves of the world. Don’t worry, the Coopers are, historically, all about taking from those who hoard their wealth from the people. They’re not exactly a family of Robin Hoods, no, but the game does make a point of showing him stealing from the Queen of England while discussing how they only steal from those who steal from the people, so, he’s got that going for him. It’s not enough to convince the cop who is always on his literal and figurative tail that he’s not the bad guy here, no, but maybe his arguments would be more persuasive if he wasn’t always asking her out to dinner. She’s still a cop even if her midriff is exposed, Sly, get it together!

The game uses a style of cel-shading dubbed “toon-shading” by Brian Fleming, the producer of Sly Cooper and the Thievius Raccoonus. Per Fleming, “Animated movies, especially the classics, feature beautiful, painterly backgrounds with fairly simply shaded, outlined characters in the foreground. With Sly, we tried to make a real-time video game that looked like this, so we use a different rendering approach for the characters than we do for the backgrounds. Typical ‘cel-shaded’ games will use a consistent look for foregrounds and backgrounds, which we really like, but it's just different than the approach we took.”

The look is rather striking, and while there is the occasional rougher edge in there that’s noticeable in the HD upscaling of this Playstation 2 original, the style still looks great on larger, modern televisions with higher resolution displays, as cel-shaded games so often do compared to their more realistically styled contemporaries. The interstitial animation that plays before and after the various game’s stages also look great to this day, and that’s similarly not surprising, since they are hand-drawn animated movies: Looney Tunes’ cartoons from the 50s still look killer, too, such is the nature of hand-drawn animation created with care and skill.

Everything is presented cinematically. Each stage gets its own intro movie and a title card. After completing a level, you get one of those hand-drawn animated movies explaining how things wrapped up and where the gang — Sly, his getaway driver Murray the hippo, and the brains of the bunch, code cracker extraordinaire Bentley the turtle — are off to next. Sometimes it can all be a little cheesy, sure, but it all fits with the image that Sly is cultivating, and cheesy can work just fine so long as it feels like it belongs.

What’s also striking about Sly is how easy it is to just pick up and play. The control scheme is an intuitive one — you jump and attack with the buttons you would expect to do those things with, and there are no complicated versions of either to contend with. There is a double jump, but there is nothing innovative about it you need to learn, other than to figure out which parts of walls you can actually double jump on top of or latch on to the ledge of, and every alternate form of your basic attack is optional. Enemies die in one hit unless they are bosses, and even those are designed for you to hit them just once before the next phase of the fight begins.

Rather than combat, the emphasis is more on stealth. This isn’t Metal Gear Solid by any means, especially since you will be doing a whole lot of skull-bashing with Sly’s family heirloom of a cane, but the stealth is mostly so you can get the jump on an opponent. They’ll go down in one hit, but so will you, and you will want to save your second (and third) chances for when you’re fighting a boss or are in a particularly tricky platforming situation. So, use stealth: watch where your foes are looking, and don’t go there unless you’re within range to strike. It’s easy enough, and feels good when it all works, too. And when it doesn’t? Well, you don’t automatically lose if you’re discovered or anything, and if you can swing your cane fast enough, you might not even give your startled opponent time to raise the alarm, either.

As said, you will lose a life if you take any damage whatsoever, whether it’s because a foe hit you with a melee attack or electrocuted you or shot you, or because you fell into water or lava or were set ablaze by a security system laser beam. There are workarounds to most of this, to varying degrees. For one, losing a life simply sends you back to the last checkpoint, but you maintain all the progress you’ve made in terms of collectibles, currency, and keys. If you lose all of your lives, you go back to the start of the level, but again, you keep everything you’ve managed to collect and any progress you’ve made unlocking further pieces of the stage you’re within. The biggest punishment is that you have to fight all of the enemies again, but that also means more currency, and maybe a second chance at finding a hidden collectible you might have missed the first time around, too, so it’s not so bad.

More in the moment in terms of workarounds are the lucky horseshoes. Collect 100 coins, and you get a silver horseshoe, which allows you to survive one fatal fall, attack, whatever. Get another 100 coins while you have the silver horseshoe, and you get the golden one, which just means you have two chances to mess up before you lose a life on the third. Gain another 100 coins while you’re already at the golden horseshoe, and you get an extra life. Despite dying in one hit and having to collect 100 whole coins (or finding the item itself out in the wild on occasion), Sly is a very forgiving game. If you get a game over while fighting a boss, you just start the boss fight over, not the whole level, and the game also begins to equip you with a horseshoe or two to make things easier on repeated attempts against them.

You’ll recover pages of the Thievius Raccoonus by defeating the game’s five bosses, which will grant you certain skills you’ll have to utilize in later levels — pressing square before you land a jump on a tiny platform, rail grinding, and so on — but you also pick up optional pages that grant you additional skills and abilities. These are truly optional skills, but there is basically no reason to avoid trying to get them. In order to do so, you need to collect all of the bottles stuffed with clues contained within each sub-level of the game’s larger stages. There are anywhere from 20 to 40 of these bottles in a stage, but don’t worry: they are, by and large, on the road you are already taking. You won’t find them all without doing some exploring or peeking behind the occasional corner, no, but they’re very often either right in your path, or might as well be flashing a light in your eyes, the placement is so obvious. The key to acquiring them is often in figuring out how you’ll get to the bottle you see, more so than hiding them. How do you climb that high? How do you reach what looks, at first glance, to be unreachable?

That’s the fun of it, and if you don’t want to bother, well, that’s your decision, but you’ll miss out on some neat tricks like dash attacks or the ability to slow down time during jumps, or the far more vital ability to fall into water or into a bottomless pit without losing a horseshoe or life.

The game was criticized for its short length, as it takes around six-to-eight hours to complete, depending on how well you do in meeting the challenges the game presents and whether or not you bother to find all of those bottled clues. It doesn’t need to be longer, though: it was a fulfilling eight hours that felt complete. Any longer, and it would have felt like it was dragging a bit. Sometimes it’s okay for games to not be longer just so they can say they are longer. Sometimes it’s a relief when a game decided it has five worlds or six worlds instead of eight: just because eight became a standard doesn’t mean everything needs to go there.

Now, that doesn’t mean Thievius Raccoonus utilized all of its time the best it could have. There are vehicle missions in each of the game’s worlds, which are meant to be a bit of a change of pace, but they mostly range from inoffensive to clearly padding. Even when they work well, they aren’t something I’m happy to be doing or have done, which isn’t a great sign. They don’t detract from the game so much as they don’t add anything to it. Now, not all of the distraction-style sub-levels feel this way: the ones where Sly is being chased by Inspector Carmelita Fox, so he has to hoof it through platforming stages while she repeatedly shoots electrified rounds at him and everything he is near? Those are great! They’re a change of pace from the stealth-oriented missions, and challenge you to not miss any of the hidden bottle clues while you’re running for your life, as well.

There is one other major issue with this Sly Cooper entry, too, and it’s that, because so many of the more advanced skills are entirely optional, the game is not built around them in any way. You get the ability to utilize decoys, mines, to manipulate your jumps while slowing down time, and so on, but those are just Things You Can Do: there is never a space in the game where you have to utilize those skills, which means you can go through the entirety of Thievius Raccoonus without using them and it doesn’t come off as playing like, a self-imposed hard mode. It’s just the game.

It would have added a bit more depth to this first Sly Cooper entry if all of these bonus skills weren’t… well, weren’t a bonus. And instead there were stages and challenges and obstacles and enemies designed around the idea that you would absolutely have them as part of your repertoire. This decision isn’t a dealbreaker by any means — Sly Cooper and the Thievius Raccoonus is still a ton of fun 20 years later — but it’s also easy to see how it could have been an even better game than it was.

And this issue is only further emphasized in the game’s final stage, where you run through a number of one-off challenges involving vehicles or gameplay you had not previously encountered. You finally have all of your skills, optional and otherwise, and then Thievius Raccoonus doesn’t really give you an opportunity to put them all to the test. The final stage still has its high points — there are some real challenging platforming sections to deal with, including against the antagonist of the game itself — but again, you can just see how things could have been even better, and it’s hard to ignore that.

All of that being said, it’s still a quality title that’s worth experiencing all this time later — there is no nostalgia present in my saying this, because my own first time playing Thievius Raccoonus was for the purposes of writing about it. The game received multiple sequels for a reason, even when its sales were poor in comparison to the other new franchises Sony was pushing at the same time (Ratchet & Clank, Jak and Daxter — maybe Sly really did need that date with Carmelita so he could join the duo squad). Even if you don’t agree that the first game itself was worth the $50 it cost to experience its runtime, these days, that’s basically irrelevant. You can buy The Sly Collection, which includes Thievius Raccoonus as well as its two Playstation 2 sequels, for $15 on the Playstation 3 or Playstation Vita digital storefronts. Now, you can’t do that forever, because both of those stores will eventually shut down, but you can make it happen as of this writing, and for half the price the digital version was initially introduced at, to boot.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.

The original trilogy of Sly games on PS2 were a big part of my childhood, so I am always happy to see others talk about the games. I know it's unlikely but I'm hoping Sony revives this series on PS5.

I enjoyed the original playing through it the first time last year, but I found the sequels semi-open world and much longer length tedious.