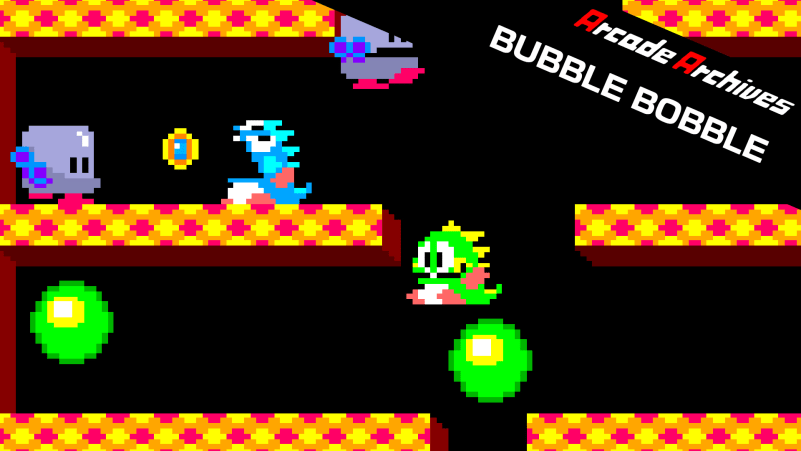

XP Arcade: Bubble Bobble

An enduring classic that spawned sequels, spin-offs, and sequels with their own sequels in arcades and living rooms around the world.

This column is “XP Arcade,” in which I’ll focus on a game from the arcades, or one that is clearly inspired by arcade titles, and so on. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Bubble Bobble is very cute. There’s no denying this. Its creator, the late Fukio Mitsuji, intentionally created a game that was cute with the idea being to “make a game that girls could enjoy.” Please excuse Mitsuji’s word choice there: this was the mid-80s we’re talking about, and his point was that arcade games were often dominated by men in production, design, and for whom they were seemingly tailored toward. Nintendo marketed the NES as a toy rather than as a video game console given the sour attitude retailers had towards games at the time, and since it was a toy, and toys as well as clothing made for kids are broken down into a boys vs. girls dichotomy to the point that even today you won’t find women characters from franchises like Toy Story on boy’s clothing, that meant they had to choose whether it was boys or girls who were going to be their moneymaker. You can probably guess which they, and everyone else that followed suit, went with.

If anything, Mitsuji wanted to give young women in arcades the chance to experience something with real depth that would normally be developed for The Boys. Bubble Bobble is undeniably cute. It is also pure evil. By the time you’re hooked a couple of dozen stages in — once you have a decent grasp on the game’s basic mechanics — the heat turns up, and from then on the game is just flat-out rude. It’s devious, in a way that its look belies: instant death upon touching a foe or an enemy projectile, enemies that go faster and faster and do so earlier and earlier, invisible timers, invincible foes that haunt you and hunt you, movements that you’ll be required to predict faster than you can think, simultaneous button presses that allow for advanced techniques which will be required to make it to the end, and oh yeah, if you go at the game solo, you’ll get the bad ending because you were supposed to be playing co-op. Bubble Bobble: the game that wanted you to get a girlfriend or boyfriend and play video games with them. Maybe the rest of the world painted video game enthusiasts as nerds or mere children at this time, but Mitsuji believed gamers could and should be having sex, too. A true visionary.

Bubble Bobble is a single-screen platformer that’s been released for roughly every platform ever, but it got its start in arcades. According to System 16, it was on Taito’s “Bubble Bobble” arcade board, which also hosted one other game: a shoot-em-up titled Scramble Formation in Japan and Tokio in North America. Mitsuji was obsessed with Namco’s arcade output at the time (which anyone who is aware of said output can certainly relate to) and felt that Taito’s own games were middling in comparison. As Mitsuji told BEEP! magazine in a 1988 interview (translated by shmuplations), “Taito’s games then seemed kind of cheap and lame to me, both in terms of graphics and gameplay. They didn’t have much style or sense. Compared with Namco’s offerings, they were very much lagging behind. That’s precisely why I harbored these ambitions and dreams, of doing something to turn things around at Taito.”

That quote could come off as a serious case of ego or self-importance, except it did come from the mouth of the guy who originated and designed Bubble Bobble, a series which has continued to this day, branched off into a second series, and created a successful sub-series, Puzzle Bobble/Bust-a-Move, that’s appeared on nearly as many platforms as the game it spun off from. Bubble Bobble is also given credit for launching the wave of single-screen platformers that would arrive in its aftermath, many of which had similar mechanics, ideas, or even looks — like with Super Mario Bros. and what followed with scrolling platformers, it wasn’t the first of its kind, but it was the one that rolled that particular boulder downhill. It also influenced Taito’s later output in terms of both quality and design, with Bubble Bobble-esque mechanics even making their way into scrolling platformers like Liquid Kids a few years later. Maybe if you’re of a certain age, Space Invaders is the first thing you think of when you hear the name “Taito,” but I imagine as you get further and further from the glory of the company’s late-70s, Bubble Bobble is the one that would come to mind first for much of a mass audience. It helps, too, that the original version of the game, nearly 37 years later, still absolutely whips and remains widely available.

You could say Bubble Bobble is unfair, and I wouldn’t necessarily argue against it, even if I’d want to quibble about what unfair means in the context of a video game. You could say it’s often impossible instead, and I’d simply shrug and say that it’s an arcade game that doesn’t ask more than anyone dedicated to dropping in more quarters is capable of learning to do. It takes time and effort to be good enough at Bubble Bobble to progress through it, to the point where doing so solo is nearly pointless: you don’t get the best ending that way, and it’s also significantly harder to pull off when you don’t have someone else to trap foes and pop bubbles with you. Later games in the series might have trended more toward single-player experiences in a world that was more living room than arcade play, but the genesis of this franchise began in the arcades with pairs in mind.

Here’s how Bubble Bobble works at its most basic: you play as little adorable dragon critters, Bub and Bob, who can fire bubbles from their mouths. These bubbles can trap enemies, who can then be popped if you touch them either with the spikes on your back or Bub and Bob’s arms — if you come flying at a foe on a jump or fall and fire a bubble at them basically as you’re about to touch them and successfully pop them that way, it’s called “kissing,” which ends up being a basically required tactic late. You can float on bubbles, too, so long as they aren’t being blown into a wall which immediately pops them: just continue to hold down the jump button and press in the direction you want to bounce to, and so long as the bubble isn’t popped by an outside force, you can just keep on bouncing upward. It’s the primary way of travel in stages where you can’t just climb platforms because of the distance between them, and like with everything else that seems optional at first, mastering this skill quickly becomes necessary.

You can pop foes one at a time, but you’ll score fewer points this way: you get point bonuses for popping multiple foes at once, and you’ll also get better bonus food to pick up afterward, too, which means even more points. Accruing points is one way that you get extra lives, with the other being collecting the letter bubbles throughout the game that, if you keep grabbing them, will eventually spell “EXTEND.” Spelling extend not only gives you an extra life, but it also automatically ends the level you’re in: that can be a significant boost late-game, when you need every edge you can get to make it out of a level without losing lives.

There are assorted power-ups that can help you out, like ones that let you temporarily become fire-breathing instead of bubble-breathing dragons, or increase your speed while making you briefly invulnerable, or shoot lighting left or right depending on which side you come at it from. There are also bubbles full of fire that will start a blaze on the first platform underneath where they’re popped, or, in a case of it being even more clear that Liquid Kids came from Taito and after Bubble Bobble, waves you ride through enemies and down the platforms. Unlike in Liquid Kids where that could kill you should you fall off of the stage via wave, though, in Bubble Bobble, it just has you falling through the ceiling and back into the stage. This, too, will go from, “hey, neat, I can do that,” to “oh God I have to escape through the floor and get to the ceiling where it will be safe for maybe half-a-second” in time.

That doesn’t mean the power-ups come without a cost, though. That fire that sets the floor ablaze? It can stun you if you touch it, as can the lightning, and in co-op this means you can accidentally interrupt your partner, briefly freezing them in place and opening them up to possible death at the hands of a still-moving enemy or projectile. Bubble Bobble is 100 percent composed of first it giveth, then it taketh away.

You also don’t want to just trap foes in a bubble because you can. You have to trap with intent to pop: if a foe breaks free of their bubble prison, they’re going to be furious. You’ll be able to tell because they’ll change color and come running and jumping at you at speeds you did not previously know they possessed, and their rage will not subside until you die. Also, if you take too long to clear a level, every single enemy becomes enraged and acts this way. Oh, and an invincible skull monster appears and begins to hunt you across the stage, and sticks around until it tastes your sweet dragon blood. Hey, did I mention that Bubble Bobble is cute?

Complete the game’s 100 levels solo, and it will basically say, “hey, good job with that boulder, Sisyphus.” You were supposed to play in co-op to get here, and the true, happy ending isn’t attainable playing on your own. Beating the game in co-op also grants you a code that lets you play a faster, tougher version of Bubble Bobble: so, 200 levels, rather than 100, and 100 was already a wildly lengthy arcade game even before difficulty is taken into context. You can speed up how quickly you can get through Bubble Bobble if you excel at it, though. Getting through the first 20 stages without losing a life opens up a hidden door that is full of point gems as well as the key to a cipher for an in-game language that has to be decoded, and gives you a hint as to how to correctly complete the game. Getting through stage 30 without dying gives another of these rooms with a message to decode as well as more points, 40 another, and if you get through 50, you teleport to stage 70, shaving 20 difficult levels — and more importantly, opportunities to lose precious lives — from the requirements. Getting through 20 stages without dying isn’t a hassle if you know what you’re doing, but everything after that is going to take practice.

There are elements of Bubble Bobble that are very much of the time, in terms of the expectation that you’ll nail pixel-perfect jumps, but then again, we’re kind of of that time in the present once more, aren’t we? Bubble Bobble is punishing, it can come off as cruel, but I don’t think it’s necessarily unfair so much as it demands you pay attention and try to do what the game wants you to do. This is a game with enemy movements that follow pre-set patterns even at high speeds, that uses invisible air currents you have to study to know how best to move yourself around and fire off bubbles to collect and use power-ups: it expects much from you, but if you take a deep breath and take it all in, you’ll find an incredibly rewarding experience with a shocking amount of depth for the day.

The source code for Bubble Bobble has been lost for longer than it hasn’t, with Taito restructuring in 1996 and then announcing their tragic whoops to the world shortly after. Obviously, this hasn’t kept them from re-releasing and porting Bubble Bobble roughly a million times. Bubble Bobble has been released and ported so many times that Hardcore Gaming 101 wrote a feature on just its eight console ports, which appear on around 20 different platforms. The arcade edition released in (duh) arcades, but it’s also appeared in various collections like Taito Legends (Playstation 2, Xbox, Windows), the Egret II Mini, Arcade Archives on the Nintendo Switch and Playstation 4, and in its own mini standalone arcade cabinets, such as a 1/4 scale (one quarter, get it?) Numskull cabinet as well as a micro cabinet produced by My Arcade. If you want Bubble Bobble, you can get it: some of the sequels are tougher to come by, but the original, which is considered one of the all-time greats for its influence, quality, and enduring nature, has managed to make itself readily available more often than not.

And you should take it up on the offer and grab a copy if you don’t already have one. Just make sure you find a friend and play alongside them: 37 years later, you don’t have to make it through 50 levels unscathed and then decipher secret text to understand that’s what the game expects of you, so half the battle is solved. The other half is pain, though, so steel yourself more than you ever thought you’d have to for a game with a pair of cutesy bubble dragon protagonists.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

I spent hours and lots of quarters playing Bubble Bobble in my tweens. I tried playing it again on the computer (sim?) but it's just not the same.