40 years of Dragon Slayer: Sorcerian

The fifth Dragon Slayer title built on the concept of Dragon Slayer III, but with a far more expansive, and permanent, goal in mind.

September marks 40 years of Nihon Falcom’s Dragon Slayer series, which had its original run ended with creator Yoshio Kiya’s exit from the company, but continues to exist to this day through subseries and spin-offs. Throughout the month, I’ll be covering Dragon Slayer games, the growth of the series, officially and unofficially, on a worldwide scale, and the legacy of Falcom’s contribution to role-playing games. Previous entries in the series can be found through this link.

What ended up being Dragon Slayer III was never originally meant for release. It was simply a project that series’ originator and designer Yoshio Kiya was working on in his spare time, to help relieve the stress of being forced to make an expansion for the smash hit Xanadu: Dragon Slayer II. As Kiya explained it in The Untold History of Japanese Video Game Developers, Vol 3., he was far more interested in doing something new and different, instead of just the same thing again, but he also understood that making a Xanadu expansion would help keep Falcom successful in a way that allowed for more opportunities to innovate. So in the end, he agreed to make an expansion to Xanadu even larger than the base game, while, on the side, working on something completely different from that.

It would end up becoming Dragon Slayer III: Romancia, also known as Dragon Slayer Jr. The reason it got that “Jr.” designation is because it’s bright and colorful and short, as well as, in comparison to Xanadu, at least, relatively simple. Stats are minimal, and rather than a series of massive labyrinths to explore, Romancia’s map is pretty small. It’s far more action-adventure than it is action RPG when viewed through a modern lens, but at this point in time, there wasn’t much difference between the two concepts, either. “Simple” is not the same thing as “easy,” though, and Romancia was exceptionally difficult to play. It was a game designed with repeated playthroughs in mind to get things right and finally complete the game, much more so than Xanadu was, and it achieved this by setting a 30-minute timer. If you hadn’t completed Romancia in 30 minutes, it was game over, time to start again. Which means the goal here was to do, basically, the most efficient and correct run of Romancia possible in order to actually complete the thing, which you could figure out how to do by failing a whole bunch of times while you explored the game.

Whereas NPCs in Xanadu were primarily shopkeepers, in Romancia, there’s a kingdom full of people who need your help, or will lend you aid or advice. They are how you find out where you should be going and what you should be doing, and by helping them out, you also raise your karma level. Which is important, because basically everything in Romancia involves raising your karma so that you can get into heaven and impress the residents there, who will in turn grant you some powers based on your karma level and needs. Rinse, repeat, solving the problems of people on the surface, raising your karma, and going back to heaven for more praise and rewards, until you can finally finish up the game as a whole in under 30 minutes.

The Famicom game — developed by Compile, who had a thing for action-adventure games in addition to their obvious love for shooting games — was the same, minus the timer, giving you a lot more time to leisurely explore and figure your way around things. It’s not that it necessarily takes less time this way, because you still have to learn everything in order to do it right, which could necessitate some restarts when it turns out you did not do what you needed to get the necessary karma levels.

Romancia might have ended up as a full game, but that wasn’t the original intent. So, when figuring out where to actually go from Xanadu, Kiya had multiple ideas. One was Dragon Slayer IV, aka Legacy of the Wizard, which leaned heavily on the pathfinder portions of Xanadu with an added twist of game design that put it more in line with games like Metroid than with its initial inspiration. The other, developed by Falcom concurrently with Dragon Slayer IV, was the fifth entry in the series: Sorcerian.

In a 1987 interivew, while it was still in development, Kiya described Sorcerian as “an RPG like Romancia… the apex of that style.” They were both side-scrolling action affairs, where there was an emphasis on speaking with NPCs and completing missions. Figuring out the little tricks and exploration both played a key role, as well. The similarity, for the most part, is in Romancia being the start of an idea, and Sorcerian being the culmination of that same idea, just much, much larger, and more expansive and involved.

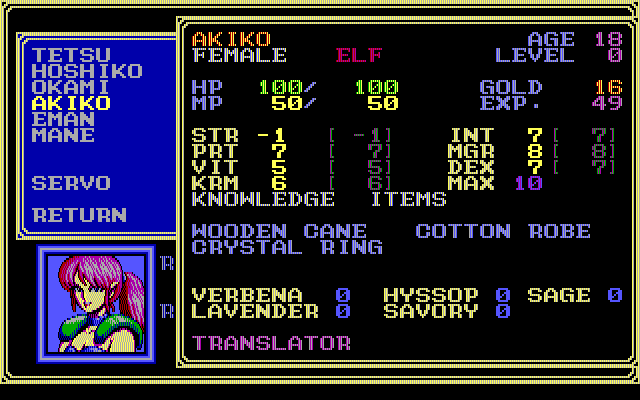

Whereas Romancia was “simple” in comparison to Xanadu, Sorcerian is complicated, and in ways that were both unique for the time and remain kind of eye-popping in how they work now. You start the game by creating characters: you can make up to 10, but you use three or four of them at a time in your active party, depending on the scenario you’re playing. Your characters not only have stats you need to determine and a class and a race and a gender, but also an occupation… you see, when they aren’t out adventuring, they need to be doing something with their time to earn money. And the occupation chosen impacts their growth, as well!

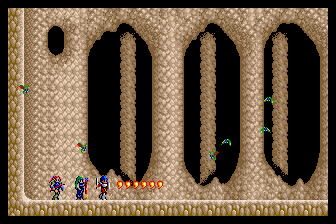

At this point, it feels like you’re getting ready to play a turn-based role-playing game where you go dungeon-crawling, but no. Sorcerian, like Romancia, is a side-scrolling action RPG, except whereas in Romancia you controlled the one character and moved around like you were playing Wonder Boy, in Sorcerian, you’re controlling all four of your party members at once. There’s one button for melee attacks from the classes that use those, and one for magic attacks for the ones that lean on spells. You can switch which party member is at the front, as well, but other than that… well, you walk and you jump, and you go through doors. It’s a bit goofy to see in action, to be honest, but it works.

The game is split up into 15 scenarios, each of which is self-contained (and one of which actually takes place in the setting of Romancia, as a nod to Sorcerian’s inspiration). You enter a scenario — the explanation for which is not in-game, but is in the game’s manual — and complete whatever mission there is to complete in order to finish it up. Enter a labyrinth or cave or forest or what have you, and retrieve the item or kill the monster or whatever it is you need to do, then collect your reward and pick the next scenario. After you’ve completed the initial 14, the final one unlocks: you can replay scenarios as often as you want in order to farm for rewards. You can also play all of the scenarios, besides that locked final one, in whatever order you choose.

It’s a bit intimidating at first, but compared to Xanadu, it’s actually not a super difficult game. Part of the reason for that is because the expectation is that, even if things are going well for you, your characters are going to die. You see, they get older the more you play, and then they eventually die. Which means you’ll need to replace them with other characters who need to be built up in the same way your previous ones were, in order to keep on playing scenarios. If you had to come from too far behind in too difficult of a game, this would be a major turn-off for players, but since Sorcerian is more about understanding how it even works than about outright challenge, the system works. We’ll come back to scenarios momentarily.

Here’s Kiya on how his perception of how magic should work in a video game changed for Sorcerian, from that same 1987 interview:

In my previous games you acquired magic as you leveled up and gained experience. The computer would give you a predetermined spell when you leveled up. I always felt there was something weird about that. Aren’t there stories that talk about magicians and wizards dedicating their whole lives to the creation of a spell? So I think magic is something people would teach to one another, not something you just mysteriously get as you become stronger.

So in Sorcerian magic is something you create yourself. I wanted to make something based around enchantments instead of “casting spells”. In this magic system, it’s like you’re drawing out the magic that is innately found in those materials. So the first time you use that magic, you aren’t really sure what exact effect it will have. Though you can kind of figure it out from the spell names.

I also wanted the combinations of herbs and the effects of items to be unknown to the player. Anyway, I wanted a game where the player could do anything, but that made balancing it very difficult.

In Dragon Slayer, spells were learned after a certain experience threshold. In Xanadu, magic scrolls were purchased, which meant magic could be performed by anyone with the cash to hand over who could also read whatever was on those scrolls. For Sorcerian, though, magic was a far more personalized experience, that involved you actively experimenting with what works and what doesn’t. You can kind of just get through the game without playing with this system too much, but, like with the aging mechanic, the system was built to be this much bigger thing, for people who wanted to really experiment and stick with Sorcerian in the long run.

Sorcerian was meant to be more than a game: it was supposed to be a platform unto itself. It was modular by design, in a way that made it, in essence, a game engine. Falcom made multiple expansion scenario packs for the game to extend your playtime with it well beyond the initial 15 scenarios, and he saw this as a way to handle game development in the future, as well, to avoid having to start over from scratch. From the massive feature at Time Extension on the subject:

"I wanted to make it like an Operating System," reveals Kiya. "At the time, using things like CPM or MS-DOS to make games, each time we had to create everything from the ground up. I got tired of doing that. So I figured, OK, I'd like to make a system where you've got the main game disk, and the data there, and then everything else can come separately as a module. That would make it easier to produce games from then on." Kiya basically created a re-usable game engine at a time when other developers were reinventing the wheel with each new title.”

On Falcom’s end, they kept producing new scenario disks so that players could keep going with Sorcerian, facing new monsters and adventures and challenges with the characters they’d created. The idea, too, was for other developers to utilize the Sorcerian modular system to create their own scenarios. And some third-party developers actually decided to roll with this plan, like Takeru and Amorphous, with Takeru operating and using Kiya’s development tools without actively working alongside Falcom at all. It’s basically the idea for Doom mods six years before Doom launched, though, part of the missing factor here might have been Falcom’s general lack of support: they wanted to move on from Sorcerian rather than utilizing it again and again, in order to use their resources and development time on entirely new games. Which is also why they ended up making just the one Utility Disk, which wasn’t for scenarios, but was basically to introduce new items and weapons and such into the Sorcerian universe, which could then be utilized in existing scenarios even though they hadn’t been part of the base game. Just like modern downloadable content, or like how Doom mods can add new weapons in way after the original game code was already written and submitted.

And, like with transferring your Pokémon from a previous generation’s console to another, you were also able to shift your PC-88 characters — from an 8-bit machine — to a PC-98, a 16-bit one. As noted by Time Extension, this, like with your pocket monsters, was a one-way trip. But it’s also one that existed more than a decade before the issue ever arose for Pokémon’s “gotta catch ‘em all” scenario, too. Sorcerian basically was ambition: in size, scope, in coding, in game design. Yes, the party looks a little funny all walking and jumping together in sync, but focusing on that misses the point.

Sorcerian might not have lived up to the full expectations of its creator, at least in terms of being this endlessly usable platform unto itself. But the potential was there, and some developers did take advantage; Falcom, too, released a number of scenarios in Sorcerian’s wake. And, they also didn’t just stop with Sorcerian, either. This is a game that was ported to multiple platforms, and rarely was it the same as it was on other ones. At first, yes, with even the North American edition released on MS-DOS by Sierra still being 16-bit and faithful to the original, but over time, that changed. The Mega Drive port of Sorcerian featured 10 new scenarios. The PC Engine port included just seven of the original game’s stages, with three new ones. Sorcerian Forever, released on Windows 95, included five new scenarios, and the 2000 Dreamcast port, Sorcerian: Disciples of Seven Star Sorcery had 10 scenarios from the original Sorcerian, as well as five additional, new scenarios.

There was also a remake, Sorcerian Original, which is the best version of the game going in a vacuum. It included not just the original 15 scenarios, but Sorcerian Forever’s five new scenarios, as well. The downside to every version of this game mentioned so far besides the MS-DOS one is that they’re all in Japanese. You can play them all, but it’s not simple to do when so much of the game involves menus and stat pages and character creation and the whole magic system based on experimentation. Which leaves you with finding the MS-DOS edition — a rarity given the game wasn’t particularly successful or even known about — or running it through an emulator like DOSbox, or applying a translation patch to something like the Mega Drive port of Sorcerian, though, the existing patch isn’t complete and is more for translating some of the most vital portions of the game like its menus. Still, it’s better than nothing when the opening menu looks like this. Imagine trying to figure out which of those many options was necessary for you to get going if you couldn’t read any of it. Not an easy thing to do, when you need to make characters and then choose which ones go into your party and then choose to go adventuring after that.

Sorcerian is plenty of fun to play, but it’s even more fun to think about, conceptually, in terms of what Kiya’s actual goal with it was. Like so much of his work, it was ambitious and ahead of its time. While the influence on action RPGs and the like was immediate with releases like Xanadu, it took a little longer for us to see a world where the ideas of Sorcerian were accepted. Maybe that’s because all of that was a bit higher concept than something like inventing a genre. Sorcerian might not have directly influenced Doom’s modding scene that keeps the original game alive with the original technology used to make it, but you can see where the two were going for a similar thing, in the same way you can see how Sorcerian beat Pokémon to the punch with character transfers into new games, and so on: Sorcerian was just wildly ahead of the game, but between Falcom moving on from it and rapid changes in hardware pushing 8- and 16-bit computers to the background not all that long after this, it’s also easy to see why the dream of Sorcerian didn’t live on through the game itself.

You can legally access Sorcerian in the present, thanks to D4’s EggConsole service on the Nintendo Switch. The PC-88 edition is the one that’s available, but at some point, maybe the versions on more powerful computers will be released, as well. Like with its predecessor, Romancia, this is one that essentially requires a translation to play it correctly: unlike Dragon Slayer or Xanadu or Legacy of the Wizard, the parts you need to be able to read aren’t already in English, and there is far more time spent in menus you need to be able to understand in Sorcerian than in any of those titles. Maybe Falcom will, at some point, return to Sorcerian again like they did throughout the 90s, only this time they’ll have a publishing partner ready to make sure the game releases somewhere besides Japan — and with some fanfare attached so people actually know it exists — too. Whether that release allows Kiya’s initial dream to be fully realized, for Sorcerian to become a platform until itself, is unknown. But hey, it’s 2024, and we just received even more Doom episodes to play, and officially sanctioned ones, too, so who knows?

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.