40 years of Dragon Slayer: Legacy of the Wizard

The first Dragon Slayer released in North America is a wildly underrated NES game that deserves a second chance.

September marks 40 years of Nihon Falcom’s Dragon Slayer series, which had its original run ended with creator Yoshio Kiya’s exit from the company, but continues to exist to this day through subseries and spin-offs. Throughout the month, I’ll be covering Dragon Slayer games, the growth of the series, officially and unofficially, on a worldwide scale, and the legacy of Falcom’s contribution to role-playing games. Previous entries in the series can be found through this link.

Dragon Slayer and its sequel, Xanadu, were wildly influential and popular… but only in Japan. Developer and publisher Nihon Falcom didn’t have either game published overseas, by themselves or anyone else, and while Dragon Slayer III: Romancia did end up with a console port, that would actually release after its sequel, Dragon Slayer IV, came out on the Famicom earlier that year. There’s plenty that’s fascinating about Dragon Slayer IV: Drasle Family, but one little bit is that Falcom actually developed the Famicom version themselves, with Namco publishing it in Japan — Dragon Slayer and Xanadu had been just for computers, at this point, Faxanadu would license Xanadu from Falcom and be developed and published by Hudson Soft for the Famicom, and Romancia’s port to the Famicom was actually handled by Compile. It’s not that Falcom was completely opposed to consoles, but they were very much, at this stage, a developer that released titles primarily on personal computers, which is at least partly to blame for why their rise and importance is more of a mystery in North America than that of Enix and Square, who had Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy, respectively, to lean on both in Japan and internationally.

What didn’t help Falcom so much in this regard, even as their own Dragon Slayer titles ended up being ported to platforms besides Japanese computers and given international releases, is that no one really knew they were Dragon Slayer games at all. While they were all numbered entries in Japan both for marketing purposes and to let people know this was the newest (usually) action RPG around, in North America, everything was kept separate. Dragon Slayer IV: Drasle Family was published by Broderbund, who also published another of the NES’ greatest out-of-context efforts from a Japanese great with Compile’s The Guardian Legend. Like with the renaming of that game — it was known as Guardic Gaiden in Japan, letting everyone know this was related to an existing Compile franchise — Broderbund changed the name from its Dragon Slayer roots, and instead went with something that fit the game’s narrative: Legacy of the Wizard.

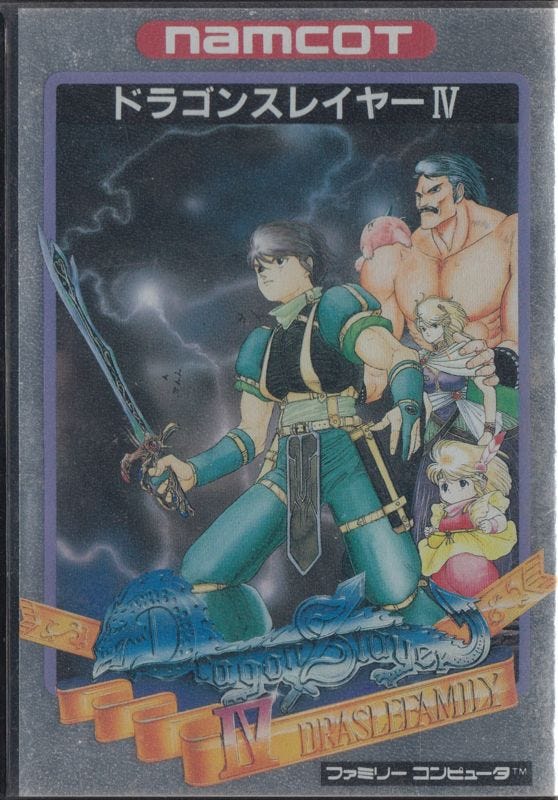

Of course Namco kept the Dragon Slayer branding for Legacy of the Wizard, since that would mean something to audiences in Japan. The top of the box art says Dragon Slayer IV, and just so there’s no mistaking it, the bottom of the box has a big Dragon Slayer logo on it, with dragon-in-shape-of-the-words and everything, once again pointing out that this is Dragon Slayer IV.

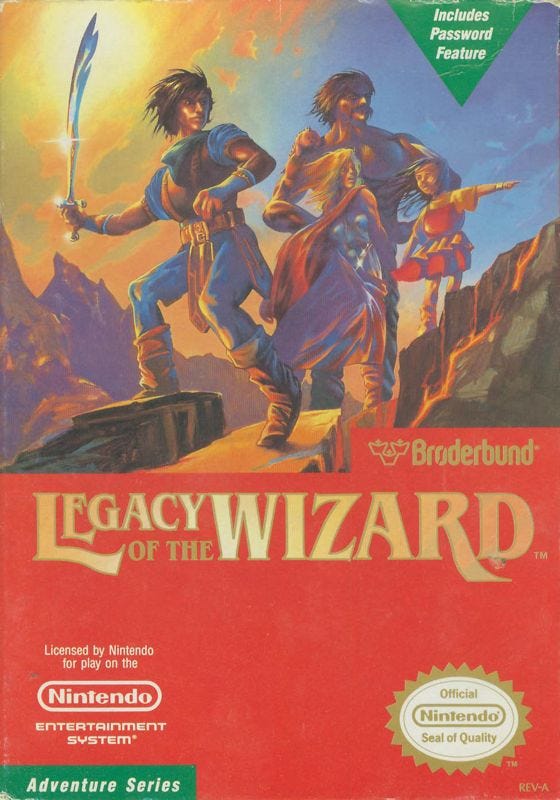

Compare that to the North American box, which just features Legacy of the Wizard as a title and the one time, but has basically similar cover art as far as characters go, albeit in a more western and less anime style:

This isn’t meant to criticize Broderbund for their decision to change things up, by the way. Dragon Slayers I through III hadn’t released in North America, and in May of 1989, when this NES port of Dragon Slayer IV was making its way outside of Japan, Falcom was already just months away from releasing the sixth game in the series, The Legend of Heroes. North America was so far behind on these foundational Japanese role-playing games in 1989: the first Final Fantasy game wouldn’t release in North America until 1990, the initial Dragon Quest wouldn’t land until August of ‘89, three years after its original Famicom release, and even something as old as Hydlide — which released on the Famicom in 1986, two years after it had come out for the PC-88 — wouldn’t show up on the NES until a month after Legacy of the Wizard.

So, saying “hey this means nothing to a potential audience and if anything labeling it as Dragon Slayer IV might put people off from playing the game” made sense. The thing that ended up confusing later on is that Sorcerian, released in North America for MS-DOS in 1990, also skipped the Dragon Slayer branding. And The Legend of Heroes did include it, albeit without a number, for the Turbgrafx-CD release of the game in 1992. Which means that North America did receive three of the 10 Dragon Slayer titles (the direct sequels to The Legend of Heroes and The Legend of Xanadu are included in that 10), and a Xanadu spin-off in Faxanadu, but there was basically no way to know in a pre-internet world that they were related at all, unless some games journalist somewhere noted as much in a magazine that you just happened to read.

I don’t remember exactly how long the time in between playing Legacy of the Wizard and discovering that it actually was a Dragon Slayer game was, but It Happened To Me, so imagine how many people who don’t mention Compile twice just a few sentences apart it happened to, as well. If I’m remembering my order of events correctly here, I already owned a copy of the game as an adult before discovering this. That’s how it goes, though, when these kinds of separations occur. And granted, they did make sense at the time, but it’s pretty easy to imagine a person who bought and played Legacy of the Wizard as a kid, enjoyed it, still thinks back fondly on it, and has no idea that it’s cousins with all of those Trails games people won’t shut up about in the present.

Anyway. Legacy of the Wizard rules. Here’s an early, post-Metroid pathfinder-style game that does away with Xanadu’s top-down combat, opting instead for two major changes: all the combat is side-scrolling this time around, and the bump combat is gone, replaced by button presses for attacks, a la Dragon Slayer III. There are still important items to pick up and equip and to use, and there’s still very much a right and a wrong way to go about things, but whereas in Xanadu you could lock yourself out from completing the game by making your karma so bad that you can’t fix it without re-rolling your character and starting over, in Legacy of the Wizard, it’s about proper pathfinding.

There are five different playable characters in Legacy of the Wizard, but this isn’t a situation where you’re picking which one you want to use and then playing as them the entire game. You’re going to be swapping through them, and regularly, in order to proceed. Pick one character to get to X item in a specific area, then play as character Y, who can utilize that item in a different area, to progress further there and then acquire a key item for character Z, and so on. Until you finally get to the point where you’ve, as you do in these early Dragon Slayer games, collect the crowns, find the titular Dragonslayer sword, and pick the one character who can wield it and defeat the dragon you’ve helplessly walked by a whole bunch of times on your way to this point in the game.

These characters are all part of a family whose ancestor — the titular wizard — sealed away an ancient dragon in a huge painting to contain its power. That seal and spell is fading now, and it’s up to this family to find the crowns and the Dragonslayer, and take care of the dragon the old-fashioned way. You’ll collect a ton of items and gold along the way, find yourself in shops where you can buy certain items for a hefty price rather than finding them organically on your route, and change your base statistics with some character-specific gear. With the end goal being, of course, slaying a dragon of legend.

Legacy of the Wizard’s map is sizable for the time period, and with the amount of backtracking and revisiting you have to do, it’s actually pretty huge:

This is a map from the game’s Strategy Wiki page, that details which sections of the map are meant for which characters to explore. At the start is the “all” section, which has entrances to the other four. Why just four sections when you’ve got five playable characters? That’s because the son in the family, Roas, is the one who will use the Dragonslayer to… well, you know. There’s no other role for him in the game besides that, and no reason to bother using him before that moment, either, since he’s unable to collect any of the four crowns that unlock the sword in the first place, and is generally weak pre-Dragonslayer.

You should familiarize yourself with the other four characters, however, as figuring out what they can do, what their strengths and their weaknesses are, what items belong to them, is how you make your way through the game at all. Pochi is a monster who is the family pet: Pochi has strong attacks, but uses up a ton of magic power to deliver them and has extremely short range, so he’s not necessarily well-suited for long excursions in comparison to some of the other family members. However, since he’s a monster, other monsters don’t bother attacking Pochi — every character can ride on the heads/backs of monsters, but Pochi is the only one who can do so without taking damage at the same time, which means he’s not taking damage unless he falls from too high of a distance. Which, in Legacy of the Wizard, isn’t very high at all, since this height matches their jump distance. Be careful about that sort of thing, especially with the ones who can’t jump very high.

This makes Pochi a great pick for scouting and item collection, if you feel you need to go in a bit tentatively to areas besides the ones he’s best-suited for, where there’s a crown that only he can reach. The father, Xemn, is as strong as Pochi, but with a longer attack range. His problem is that he can’t jump very high, so he’s a bit limited in where he can go. Get him the Gloves, however, and he can move blocks around, making his own paths. Meyna, his wife, is a wizard with an even longer attack range than her husband. Her true strength is in the ability to use certain items like the Key Stick for opening locked doors, or the Wings to open up her movement potential. Their daughter, Lyll, is an archer. and also the best jumper in the family. She’s very weak as far as attacks go, but has the furthest attack range, so you can at least get the jump (heh) on foes that way. Lyll can also equip the Jump Shoes to be able to jump even higher, and since she alone can use the mattock for some reason, she can also break blocks.

There is a lot that goes into thinking about which section to start with, which characters to use when, and it goes beyond the basics of “well if I collect this item then this character can explore their entire section of the map.” The bosses, for example, each become more difficult the more of them you’ve defeated. So you have to consider whether leaving a particular boss for later makes sense when a different boss might be an easier fight in that position. And there are also two very different approaches you can take with the game as a whole: do you want to complete this as fast as possible, or do you want to better ensure your success? This is where it should be pointed out that, if you die and don’t have an elixir to revive you, the best you can do to recover your progress is a password, not a save.

The “safe” method, as Strategy Wiki calls it, has you playing each character at least two distinct times, in order to first collect every item that can be collected, and then for a second run, going in to face the various area bosses in an order that will make your life easier, with characters that are the best fit for that boss in particular. The “quick” method involves far less backtracking, and is absolutely not for beginners since you’re going to need to be pretty great at the game to take on the powered-up bosses late without the optimal family member to handle that task. Legacy of the Wizard isn’t a game where you can just avoid taking damage and slowly whittle away enemy health until you finally win. You have a magic meter that powers your attacks, and when it’s empty, you can’t attack anymore, not without finding a refill item or having a magic bottle on hand. This probably goes without saying, but you can’t kill a boss you can’t attack.

You can play Legacy of the Wizard as this big open playground where you have to figure out every secret for yourself, where you have to discover which character should explore which section, which items are meant for them, which boss should be taken down in what order, and so on. Or you could play using a guide like the ones provided by Strategy Wiki to point you in the right direction: you’re still in need of actually doing everything there, as these guides are more “go to Pochi’s section to get this item and this item for Xemn” than they are a blow-by-blow walkthrough. It’s both more open and more closed off than what Metroid and Castlevania would eventually get up to, since it’s not defeating bosses that opens up new sections and new powers, but simply exploring until you find… something. And then using that something with a different character to find another something, somewhere else, and so on, until you’ve found it all. In between, you’ve got to survive, which is easier said than done in a game with fall damage, tons of monsters, and a limit to how many attacks you can make without refilling your ability to attack.

Like with a Metroid, it’s only a truly difficult game if you refuse to engage with it on its own terms. It’s full of secrets to unearth, passageways and items and skills, and taking the time to discover and master all of them will make for both a better game and improved experience. It takes more effort, of course, but less of the slamming your head against the wall variety, and more the kind of effort that goes into mastering something worth mastering.

Legacy of the Wizard has distinction as the one NES game that industry legend Yuzo Koshiro composed (he’s credited as Koshiron within). There isn’t a ton of music in the game, as was normal for the time — there are 14 tracks, a treasure chest ditty, and an unused song that take about 17 minutes to listen through — but it’s all great and catchy. Koshiro and Dragon Slayer originator Yoshio Kiya are both on the record as saying, by way of Untold History of Japanese Video Game Developers, that though “Quintet” is included in the credits for Legacy of the Wizard, that’s just a coincidence regarding the eventual studio, Quintet, that would be formed by ex-Falcom employees, and had to do with a group of five within the company who worked on the game. So no, there’s no direct line between Dragon Slayer IV and ActRaiser or what have you, other than what already existed in terms of ex-Falcom moving on to make their own studio.

Legacy of the Wizard is not without some minor faults. It can feel a bit buggy at times, and it’s one of those games that really makes you feel the lack of saves and autosaves of late-80s technology. It offers you essentially nothing but an invitation to explore in terms of guidance, especially if you don’t have access to a manual that explains just what your goal even is here. But in the end, all of that is fine. If the game is ever re-released in a remastered form, those bugs should be fixed, saves added, maybe things made a little more clearer to account for us living in a manual-less world now, but basically nothing else should change. Keep it a 2D side-scroller! Keep the exact setup for gameplay and progression! Keep it as it is, because what Legacy of the Wizard already is just happens to be one of the most ambitious and rewarding games on the NES.

Luckily, it’s also a game you can access right now, and even legally, if you care to play it as is. The Famicom version that Namco published is available for purchase, as part of Namco Museum Archives Vol. 2. This is a two-part collection of Famicom games — ports, originals, and demakes — that Namco either developed or published, and they include save states and rewind. Both of which can be very helpful in a game like Legacy of the Wizard, if you’re not in a place where you can go at it original style. Like with the standard Namco Museum collection, this is regularly discounted, so keep an eye out, though, it’s also just $20 for 11 games, so you’d be getting Legacy of the Wizard for less than two bucks even at full price if you want to think of it like that.

To bring things full circle, for the Namco Museum Archives release of Dragon Slayer IV, Namco updated the title screen to look just like Broderbund’s version of it, only with the appropriate Namco credit in place, rather than the Drasle Family title that looked a lot like the MSX2 release’s. This is because, as unfamiliar with Legacy of the Wizard as North American audiences might be in the grand scheme of things, it probably made sense to market this to them with the name they might know, rather than as Dragon Slayer IV. They really should have blown some minds and called it Dragon Slayer IV: Legacy of the Wizard, though, forcing a connection on some people who hadn’t gotten there yet.

In addition to this Namco Museum Archives release that’s available on the Switch as well as modern Playstation and Xbox consoles, you can also pick up the MSX2 version of the game with its Dragon Slayer branding intact through D4’s EggConsole project. This, too, has save states and rewind, and since pretty much everything is already in English or is represented by pictures, anyway, you still don’t need it to actually be translated in order to play. The Famicom and MSX2 versions were released a week apart, with the MSX2 version the superior of the personal computer editions, so this isn’t a situation where Legacy of the Wizard was later ported to fit the hardware: it was made with both in mind from the start, and developed concurrently, too. Grab whichever one you feel like, though, the EggConsole one is only for Switch users. What’s important is that you give this game a chance in the present, both to enjoy yourself and to swell the ranks of those who can annoy Falcom about getting around to eventually remaking it.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

"The thing that ended up confusing later on is that Sorcerian, released in North America for MS-DOS in 1990, also skipped the Dragon Slayer branding."

Very interested if that was a deliberate move by Sierra head Ken Williams. He was instrumental in bringing it over, from what I've read, and Sierra adored big franchise installment numbers. You'd think he'd be fine with the DS4....but maybe he was concerned that people would look for the nonexistent prequels that they had no intention of bringing over.

Some friends of mine had Legacy of the Wizard for the NES back in the early 90s and I, as a US tween at the time, had no idea about Falcom or Dragon Slayer or anything else of that nature. But my _mind was blown_ by the tantalizingly huge world LotW laid out. The idea of multiple paths and different powers for different family members, each offering different routes, each of which would need to be explored, was so far beyond anything else I'd seen previously, even in my beloved Final Fantasy (no #, since we didn't need those yet). Incredible.