Retro spotlight: Dragon Quest

There are few singular games more vital to the success of video game consoles than the original Dragon Quest.

This column is “Retro spotlight,” which exists mostly so I can write about whatever game I feel like even if it doesn’t fit into one of the other topics you find in this newsletter. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Yes, Dragon Quest built its own foundations using video game conventions that came before it, but the Chunsoft and Enix project still created something new in the process, something as influential as anything that came before or after it. The Japanese console role-playing game began with Dragon Quest: if you think the original Final Fantasy, Phantasy Star, or Legend of Heroes play like obviously old-school JRPGs, well, they had already made advancements on the formula that the first of their kind had created a few years prior.

Wizardry and Ultima, early western role-playing series in the 80s, had a huge influence on Japanese video game development — and still do, as FromSoftware devotees are aware of every time their Souls character can’t swing their sword in a cramped hallway, or gets murked because they didn’t pay enough attention to their surroundings. While it was possible to make these games for home computers, consoles were another story: the cartridge technology of the time simply didn’t have the kind of storage capable of containing these lengthy adventures. Dragon Quest changed this: by implementing a password system, players could pick up where they left off. Yes, the original Dragon Quest came out so early in the industry’s life that utilizing passwords to “save” progress was a revelation.

It was no small thing, though, as it not only made an expansive RPG the kind of game that could be played on a console, but it also allowed for other JRPGs to exist at all. Hironobu Sakaguchi has said that there is no Final Fantasy without the success of Dragon Quest, and even cited the password system as one of the reasons he was able to develop his RPG ideas for a console market suddenly hungry for them, instead of for computers. While companies like Falcom originally kept making their various JRPGs on computers instead of consoles, many of these titles would end up ported to the various consoles, by Falcom themselves or studios they licensed their works out to, such as Hudson Soft. You can thank Yuji Horii for this expansion of the industry: he wanted to make a somewhat streamlined RPG that could be enjoyed by a larger audience newer to video games, and he certainly succeeded in that.

It might sound odd to say Dragon Quest was kind of like an RPG 101 course, given how it might play today to those used to more modern entries in the genre, but Horii meant in comparison to the complex systems of a Wizardry or Ultima. Those games were punishing grindfests — this is not a criticism, by the way, just the nature of them — or highly customizable in a way that could be an impediment to people who did not or did not want to understand the rules of tabletop role-playing games such as Dungeons & Dragons. Dragon Quest took care of your stat upgrades for you, the menus and options were simplified from their inspirations, and the world, while larger than console gamers were used to, had five years after the original Ultima to figure out how to present an open-world as something manageable even to beginners.

Horii did not just take inspiration from these established RPGs — the menus and storytelling were influenced by his own work, such as the Famicom adventure game The Portopia Serial Murder Case. That title had a significant influence on the rise of adventure games and visual novels in Japanese game development, for titles like Famicom Detective Club and Metal Slader Glory, and Horii then went on to help form what would become the distinctive Japanese role-playing game through Dragon Quest — not a bad career, that, and it was still in its infancy.

Horii used to be a writer for the popular Weekly Shōnen Jump, prior to his involvement with video game development. Dragon Quest was developed by Chunsoft, just like The Portopia Serial Murder Case, but it was also a Weekly Jump project, as editor Kazuhiko Torishima tells it. The magazine began to review video games that released for the Famicom, as kids were more likely to have one of those in their home rather than a more expensive computer, and also included special cheat codes these kids couldn’t wait to get their hands on. This all predated the long-running Famitsu magazine, too: video game reviews weren’t really a widespread norm of the time, not yet. It’s not that they didn’t exist at all, it’s just that there’s a reason that the “Reception” section of so many Wikipedia pages on very old games just tells you how popular they were at arcades instead of including review scores or critics’ quotes.

Anyway, things escalated from reviews to outright game development at Weekly Jump:

“We then came up with a new idea, as our current structure had reached its limit. So the idea was to show to our readers how a game is developed. Starting from the very early concept stages, all the way through production. As it would be our own game, the information would then be exclusive. So this is how Dragon Quest started.

“At this time, Horii started his work at Enix, on games like Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken and Okhotsku ni Kiyu: Hokkaido Rensa Satsujin Jiken. In addition, myself and my team were crazy about role-playing games on Apple, like Ultima. So I thought we should do a role-playing game with Horii as the scenario writer. However, if we had just these things it would mean we wouldn't have the justification to include it in Weekly Jump. This is why I decided to add [Akira] Toriyama to the project for the character designs.

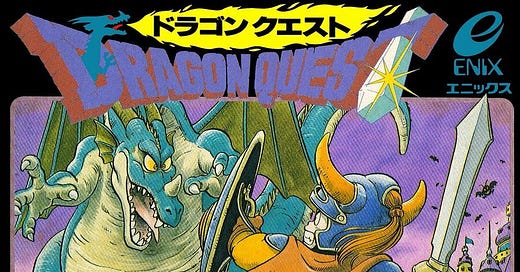

Akira Toriyama, of course, is responsible for Dragon Ball, and his distinctive art style helped Dragon Quest’s box really pop on those store shelves. (The box art and art inside the manual was changed for the North American release, to have a more western style, and while it’s not ugly like some localized art, Toriyama’s style really did set the game’s box apart from your more “generic” manga art. The entire manual for the Japanese edition, by the way, has been scanned and uploaded, if you’re into that sort of high-res thing.) Torishima made the development of Dragon Quest a Weekly Jump project, so that its development could be covered from start to finish and they could also write a book on the game, but he also made sure that Shueisha, the publishing company behind Weekly Jump, had no rights to the game’s intellectual property. In Torishima’s words, it was “to protect the game from getting ruined,” as his manager didn’t understand video games, and including them in the decision-making process could have been disastrous. Enix bankrolled the game, and Weekly Jump staff, present and former, developed it with Chunsoft.

The rest is, quite literally, history: Critical reception was as high as fan reception, and Horii’s goal of an intro RPG built for the ever-growing console market full of newer players was achieved to the point that Dragon Quest II would release all of seven months later. Dragon Quest has been considered the “national game” of Japan, which… does the United States have a national game? I hope it’s DOOM. Regardless, you can’t do much better than spawning a series now approaching its 40th year that redefined a genre, promoted the growth of video game consoles, is full of spinoffs, and is beloved by Ichiro Suzuki. But being called the “national game” manages that.

By the time Dragon Quest reached North American shores, it was three years later, 1989, and Dragon Quest IV was already in development in Japan, and would release there six months later. Nintendo of America would publish the game — re-titled Dragon Warrior due to trademark issues — instead of Enix, and it would undergo graphical updates to put it more in line with the expectations of ‘89, as well as receive a battery back-up save system in the cartridge that removed the need for passwords. The game’s localization was written in a very Elizabethan style of English, which honestly made things a little tedious: between how long it took to say things using that style of English, and how slow the text scrolled even when set to the fastest setting, every little thing involving text in Dragon Warrior took too long. That’s not to say the localization is bad — it’s alright, especially for the time, it’s just forever-taking, an odd stylistic choice that didn’t mesh with the technology of the time.

Koichi Sugiyama, who had already composed for decades before working on Dragon Quest, wrote the soundtrack for the original game, and also scored each of the 11 mainline entries in the series prior to his death in September, 2021. Even if you’ve never played the original Dragon Quest, you’re going to recognize, at minimum, the style. His classic style was also a fit for an orchestral arrangement, the first of which occurred in 1986 with the London Philharmonic. The embedded symphonic suite below is marked as from the 25th anniversary of DQ, however.

The game was not nearly the hit in North America as it was in Japan, though, it did work to help sell Nintendo Power subscriptions. If readers subscribed to the magazine, they would receive a free copy of Dragon Warrior, which Nintendo had more of than they knew what to do with given North America’s chillier reception toward the title. Should have kept that Akira Toriyama artwork on the box instead of going for the more generic, western RPG-inspired look, clearly. As Frank Cifaldi wrote in the above linked post, Nintendo of America didn’t license the Dragon Quest sequels, only published the first Final Fantasy title, and then didn’t bother localizing and publishing Nintendo’s own Mother — itself a love letter to Dragon Quest. Nintendo would eventually come back around on Dragon Quest, though, as the west did: while the by-then merged Square Enix would handle publishing duties of the Dragon Quest DS remakes in Japan, Nintendo took over publishing duties for VI, VII, and VIII, and published the brand new IX exclusively for the DS, as well.

How did Dragon Quest play? It was very much of its time, but even more so than is usually meant by that statement, since it was kind of blazing a new trail here, and the refinement to the series and genre would come later. You spend a considerable amount of time in Dragon Quest walking around and talking to NPCs in order to get clues about which direction you should head next, and while walking to those destinations, you will grind in turn-based battles through menu selections. When do you stop grinding? Once you’ve got enough money to afford all the new gear in a new town is the general baseline for that sort of thing. You’ll notice when the enemies around you aren’t giving nearly enough in gold compared to the local equipment costs, though, and in those cases, you’ll just need to make a note that you’ll need to come back here at a later time, after you’ve amassed a fortune elsewhere.

One thing Dragon Quest did that was very new was to begin the game with the damsel in distress trope, but not make that the point of the game: instead, rescuing the princess from the clutches of a dragon is just step one, both for learning how the game works and narratively speaking. Once you’ve saved her and brought her back to the king who set you on your adventure in the first place, you’ll realize there is more grinding and exploring to do, and bigger baddies to cleave in two, as well.

As old-school, open-world games tend to do, you’ll know you’re somewhere you’re not supposed to be yet when the enemies are suddenly tearing you apart. New equipment and leveling up solves all that ails you in Dragon Quest, so sometimes all you need to do is find a space with plenty of experience and gold to acquire that you can also survive without risking death, and then go back to wherever you were having trouble and try again. Obvious stuff now, but it was how Chunsoft extended the game’s play time and was also what the progression systems were based around at the time when they were much newer concepts, especially to those unfamiliar with existing RPGs on computers.

I like the original Dragon Warrior well enough, despite the pace of the localization, but if you’re going to experience the first game in the series, you should go for the Game Boy Color remake. As it’s on an 8-bit handheld, it doesn’t stray too far from the original sensibilities and design, but advancements in programming and 8-bit art had advanced enough at that point that it’s still a real jump in visual quality from the original. It helps, too, that, rather than being a from-the-ground-up 8-bit experience on the GBC, the Dragon Warrior remake is actually a scaled down port of the Super Famicom remake of Dragon Quest: so, you get much more detail in environments and Toriyama’s excellent enemy sprite designs that persist in the series to this day, but it’s still very clearly an 8-bit experience that is true to the original designed-for-8-bit style. Unlike, say, the mobile and Switch ports that have since released, which are the same kind of ugly that Square Enix is always responsible for with their mobile ports of classics from the era of sprites.

The Game Boy Color remake also does an excellent job of re-balancing the game. It’s hard to know when things are off when you’re in the process of inventing them, or because of the technological limitations of the time, but the GBC Dragon Warrior not only uses a new localization by Enix that cuts the tiresome Elizabethan pacing out of the text, but also reworked how much experience and gold would be received from foes. It might not sound like much to get two experience points and four gold from a red slime in the game’s early going instead of one and two, respectively, but that means you spend half as much time fighting random battle in the game’s opening hour in order to buy your first shield and a non-blunt weapon.

The encounter rate has also increased, which can be a little annoying later on in the game when you’re constantly walking back-and-forth across the game’s map, but is a blessing early, since you spend less time not in battle during the segments where what you really need is to always be in battle, in order to earn the XP and gold necessary to progress. All of this is worth it to not have to select “Stairs” from a menu in order to climb or descend stairs, though: Dragon Warrior remake’s internal logic is based on the improvements in the genre and series that came after the original, and they are very welcome ones.

This is my preferred version of the game, and, artwork aside, is the one you can find on mobile or the Switch even today. Again, those have the weird sprites-out-of-place look to them that I simply can’t stand, so I don’t blame you if you go and find a copy of the original GBC remake (which also includes a remake of Dragon Warrior II) somewhere instead because you don’t want to encourage Square’s bad habits. If you just want to experience the game, though, to see where Dragon Quest has been relative to where it is now, the mobile and Switch versions are available, and inexpensive, too.

The original Dragon Quest surely is not for everyone, not in its original Japanese form, its localized North American form, or even in its remakes. It’s a very old-school, grind-heavy experience, and while easier than the games it drew inspiration from, it still isn’t much for hand holding. You’ll be punished for your mistakes, often egregiously, saving is a bit of a chore that requires significant backtracking, and the game’s length owes much to its grind. And yet, it’s also easy to see, even now, how this was the game that inspired such a change in how Japan’s game development would focus: consoles were now capable of what was once only the realm of computers, and given their comparative price points, this meant more and more people would be able to play RPGs than ever before. If you’re fine with old-school RPGs and have never experienced where the Japanese sub-genre got its start, you should.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

I started on IV but number I is just so genre defining, perfect start for the series.