Past meets present: Famicom Detective Club

The Japan-exclusive Famicom-era games The Missing Heir and The Girl Who Stands Behind released worldwide in remake form in the spring of 2021. How do these early visual novel mysteries hold up?

This column is “Past meets present,” the aim of which is to look back at game franchises and games that are in the news and topical again thanks to a sequel, a remaster, a re-release, and so on. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Do you know how annoying it was for Nintendo to announce that they would be releasing a pair of games that were previously Japan exclusives from the Famicom era, while I was in the middle of ranking the top 101 Nintendo games ever? Extremely annoying. As someone who just likes to play video games, I was thrilled to get my hands on games that I had not, at that point, had a chance to check out: as someone in the middle of a project that ended up taking 10 months to write plus nearly as long in pre-writing preparation to put together, I’m surprised I didn’t develop an eye twitch.

Luckily, the Famicom Detective Club duology is really good, but not top 101 good, so I don’t have to start making revisions in my head to a project I would like to let rest for more than a month. The digital bundle is absolutely worth your time and money regardless of its ranking or not ranking status, if you’re into visual novels and detective games: if not, they probably aren’t going to change your mind about the genre, given they are very much games from the late-80s, released a lot closer to the origin point of visual novels and adventure games, only with a 2021 coat of paint on them. If the ambition and manipulation of the form by games like Gnosia and Doki Doki Literature Club and the like aren’t getting you into visual novel-style games in the present, prettier versions of games from Nintendo’s first home console probably aren’t the answer for you, either.

With that being said, if you are into visual novels and point-and-clicks and this kind of text-heavy style of adventuring, than you’ll likely enjoy Famicom Detective Club’s two titles: the genre as a whole, with its emphasis on plot, on narrative, on memorable characters, on tension, ages well, and this duology is no different. The story for both is really good, with just the right amount of intrigue and curveballs thrown at you to keep you guessing until the end, though, the first of the games is a bit better about that, and sticks its landing more effectively, too. I kept thinking I had things figured out in both cases, but that was not always the case, which felt good. This kind of balance helps you feel smart while playing — like a detective figuring things out! — but not bored, since you’re not just waiting for the resolution you know to be coming. The plots have more to offer than that, and neither sticks around longer than they should, either, at about five hours each.

You can play the two games in any order, really. The Missing Heir was released first, in 1988, but the sequel, The Girl Who Stands Behind, is actually a prequel. The protagonist, Taro Ninten, has lost his memory in The Missing Heir, but that’s used as a plot device to hide specific details about the case you’re working on from the player, details exclusive to this game. So, if you want to play The Girl Who Stands Behind first, you can, without spoiling that Taro is a detective or anything like that. It’s like, the first thing he learns about himself after losing his memory, that he was a detective working a specific case he now remembers nothing about.

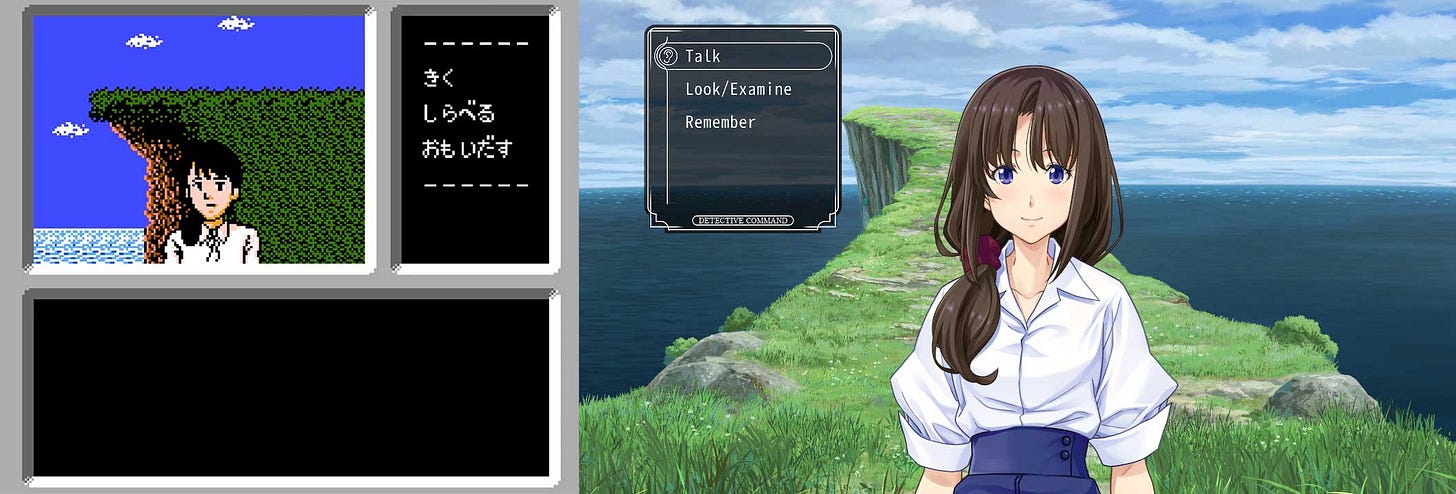

While you can play these two games in whatever order you please, there is little reason to play them in chronological order: Nintendo didn’t remake these games to have the exact same systems in 2021, or anything like that. The Missing Heir is just like it was in 1988 on the Famicom, except designed for the Switch. The sequel prequel, The Girl Who Stands Behind, has some quality of life improvements and in general plays a little better and more player-friendly, because Nintendo R&D1 took what they learned from developing the first of these two games and then applied it to the second one. Because of this, it feels like going backwards, mechanically, to play the prequel before the sequel. It’s not a huge deal from a big picture point of view, but it is a tiebreaker for play order I didn’t know I was going to encounter until I had experienced both games.

The gameplay of The Missing Heir “suffers,” for lack of a better word, from issues that so many visual novels of a certain era, especially mystery ones, do. You have to keep plugging away and guessing, sometimes in very non-obvious ways. At least here, unlike with Snatcher, which also has these issues, no one is accusing Taro of being a pervert for guessing wrong or looking too long. But like Snatcher, these design problems aren’t gamebreaking or anything: you just need to plug away until you find the right combination of queries and investigative points to move on, and that sometimes takes a little longer than you want. The other elements of the game make up for this disappointment, or at least, do for me.

The Girl Who Stands Behind is better about gently guiding you from question to question, from investigative selection to investigative selection, without making it so obvious that you feel like you’re on rails. That, combined with the switch from The Missing Heir’s “Remember” system, which you use to try to recall lost bits of Taro’s memory after having certain conversations or finding certain items, to The Girl Who Stands Behind’s system which is just used to think things over, helps make for a smoother experience. It’s a little hard sometimes to remember what Taro has forgotten when you don’t know what Taro has forgotten. Whereas learning something that seems significant, or at least could be, inherently nudges you toward thinking things over, in the hopes Taro has some kind of epiphany like you just might have.

It feels like it wasn’t just the sheer volume of Japanese text present in a visual novel/adventure game that kept Nintendo from localizing the Famicom Detective Club games until now. They basically check off every possible box, outside of invoking religion, that would keep the late-80s/90s version of Nintendo of America from being interested in a regional release. These games involve murders and blood, lots of both, and they can be brutal kills even though the images were mostly static ones. Cigarettes are not just present for a little bit of detective mystery aesthetic, but are actually a significant, inextricable part of one of the games. This isn’t a situation where Nintendo of America could just decide that booze is coffee or milk in their version of the game, like they did to so many others.

Their options were to just suffer the public relations, won’t-anyone-think-of-the-children consequences of releasing a game with those elements they shied from, or to not release it. And since this is a specific era of Nintendo of America we’re talking about, they chose the latter, even though these were games written by Yoshio Sakamoto, who you know from his work on Metroid. It was his first job writing the scenario for a game, and he went all-in by writing said scenario in book form before they even got to work programming the thing. Like I said, there’s a reason all of those elements hold up, allowing for a release in 2021. Mistakes in Metroid: Other M aside, Sakamoto knows how to tell a tight, thematic story, and succeeded at it even at this early stage of his career.

While this is just the second-ever release of the original Famicom Detective Club, The Missing Heir, the prequel game, The Girl Who Stands Behind, has seen life on other systems prior to its Switch release. First, it was released on the Super Famicom in 1998 — remember, Nintendo kept releasing Super Famicom games well into the Nintendo 64’s lifespan in Japan, even as North American releases shut down years prior — and then again on the Game Boy Advance in 2004. There was also a spinoff, featuring Taro’s partner in these two games, Ayumi Tachibana. BS Tantei Club: Yuki ni Kieta Kako came out in 1997 for the Satellaview, a Super Famicom peripheral that allowed for the downloading of games and more, basically Nintendo’s equivalent of the Sega Channel for the Genesis, but exclusive to Japan. I very much want to play this game, just to see what it’s like, but that’s not necessarily an easy task.

Still, Ayumi ended up being the more popular character of the two, even if she wasn’t playable in the original Famicom Detective Club titles. She got a spinoff, and is also a trophy in Super Smash Bros. Melee on the GameCube. Masahiro Sakurai even considered her as a fighter for that game, which… honestly if they want to make Ayumi the last fighter in Smash Ultimate, well, I’d never stop laughing at how angry that would make some folks, so they should do that. Give her a sword while you’re at it.

My suspicion for why the Famicom Detective Club games were localized now, over 30 years later, was that Nintendo was planning to revive the franchise, this time as a worldwide one. Visual novels and adventure style games are popular, and while Nintendo had steered clear of making them for a long time, they can certainly get back to that and expect to make fans happy for doing so, and also money. Mages, the developer that handled the Switch update of these games, has expressed interest in making a brand new entry, and they certainly could. Whether it’s featuring the original characters, Taro and Ayumi, as the detectives, or the two of them as the head of the agency they worked for all this time later with some new protagonist barely matters: there is fertile ground here for a revival, or a number of new sequels, given the games revolve around a detective agency solving mysteries.

Regardless of whether we see any new entries in the Famicom Detective Club franchise, though, these two games are here, and worth your time. You have to be into this kind of adventure-style, visual novel-y genre to get into them, sure, but it feels like there are more people into that kind of thing now than there ever were before. And they’re onto something here.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.