40 years of Dragon Slayer: The Legend of Heroes

The studio and series known for action RPGs gave a turn-based RPG a shot, and with success.

September marks 40 years of Nihon Falcom’s Dragon Slayer series, which had its original run ended with creator Yoshio Kiya’s exit from the company, but continues to exist to this day through subseries and spin-offs. Throughout the month, I’ll be covering Dragon Slayer games, the growth of the series, officially and unofficially, on a worldwide scale, and the legacy of Falcom’s contribution to role-playing games. Previous entries in the series can be found through this link.

Thanks to the comparative Japanese exclusivity of much of their early library, Nihon Falcom doesn’t always get the credit they deserve for being as integral to the proliferation and advancement of Japanese role-playing games as they should. While Enix and Square created and refined the turn-based RPG with their Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy series, Falcom was leading the way with the Japanese action RPG, in a number of forms, courtesy Dragon Slayer and Ys. Falcom wouldn’t stay exclusively in the action RPG space, however: in 1989, it was the genre-hopping Dragon Slayer’s turn to take them into the world of turn-based RPGs.

Dragon Slayer VI is otherwise known as Dragon Slayer: The Legend of Heroes, and it got its start on NEC’s PC-8801 before being ported nearly everywhere in Japan. The PC-9801 release came in 1990, as did the FM Towns and MSX versions, and then it finally made its console debut in 1991, on the PC Engine CD. The 1992 Turbografx-CD port would signal the lone North American and English release of The Legend of Heroes, and then it was back to Japan exclusivity, with the Super Famicom, Sharp X68000, Mega Drive, Playstation, and Sega Saturn also receiving releases, with the most recent (and last) official release of the game coming by way of the Wii Virtual Console in Japan. There was one other non-exclusive release, an MS-DOS port of the original, but that came out in South Korea.

This first Legend of Heroes release was the only one to arrive in North America for years and years. It took until the game was already three years old for it to leave Japan — the sequel and final Dragon Slayer game, The Legend of Heroes II, was already nine months old in Japan by the time the first game released elsewhere, and that was two Dragon Slayers later as well — and then North America didn’t see another The Legend of Heroes title until 2005’s Playstation Portable game The Tear of Vermillion, which was a remake of what was actually the fourth entry in the series, the initial release of which was in 1996 for the PC-9801. Oh, and it was also the second in its trilogy. It’s best we don’t talk anymore about how confusing the numbering and naming of those later Legend of Heroes games got in translation, but just know that, even with Dragon Slayer sunsetting after creator Yoshio Kiya left Falcom, it lived on through a pair of spin-off subseries: Xanadu, which last had a new game in 2015 (2017, 2024) with Tokyo Xanadu (eX+, and the updated Switch version of eX+), and The Legend of Heroes, which is far and away Falcom’s largest series at this point in every sense of the word, as it even has its own subseries, Trails.

It’s pretty easy to see why the original The Legend of Heroes game didn’t thrive in North America: it never really got the chance to. As said, it was already three years old by the time it left Japan, and in RPG years at that point in the genre’s history, you can absolutely feel the time dilation. That’s not to say that The Legend of Heroes is a bad game, because it’s not: it’s certainly worthy of standing alongside the likes of turn-based classics such as the first Dragon Quest/Warrior, Final Fantasy, and Sega’s Phantasy Star, with its own little wrinkles to add to the genre and play. The problem is that, by the time Falcom’s first go at the genre released outside of Japan, the international market already had two years of experience with Phantasy Star II and Dragon Warrior II, a year of a world where Final Fantasy II (IV) existed, and nine months of Dragon Warrior III. These games had taken major leaps forward from their predecessors, and were in turn well ahead of some of what the inaugural The Legend of Heroes had to offer.

Of course, even if Dragon Slayer VI had been light years ahead of these other classic and foundational RPGs, the fact it was relegated to the Turbografx-CD in North America did it no favors. It might have been a killer system, but it was a killer system that no one outside of Japan owned — Hudson Soft didn’t bother localizing the second game, like they had the first, even though they published the PC Engine CD version of the game in Japan.

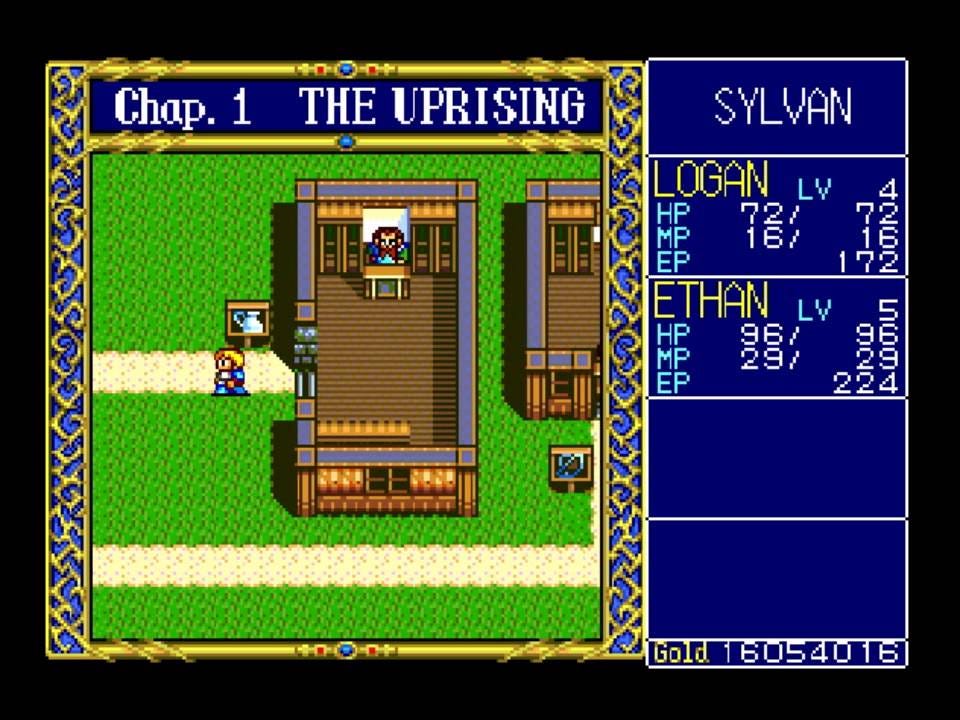

The Legend of Heroes plays in that Dragon Quest style that was so popular: walking around a larger world and towns, chatting up the locals, and with detailed sprites of your foes fully visible in battle that are far ahead of the graphics elsewhere in the game. Instead of seeing your own characters, you just see their stats, and much of the battling occurs in text form instead of with any animations. There are flourishes for physical and magical attacks, sure, but you don’t see the swords or the staves or the people wielding them, is all. There’s a pretty good flow to the battle system, as old-school as it is, since you can crank up the message speed, and even if you just mash the button to move the text along, it will be sure to change its delivery cadence a bit to let you know that someone has been knocked out or hit with a status effect you need to account for.

There is also a very customizable auto-battle setup, that will let you determine what kinds of battle plan your characters are going to enact, even to the point of limiting or increasing their healing and magic usage. It can be helpful if you just don’t feel like doing the work yourself, but if you’re perfectly fine with transporting yourself back to 1989 and manually fighting loads and loads of random turn-based battles that blend together, then you won’t need to utilize this system.

The decision to make a turn-based RPG with random battles was a curious one for Falcom at the time, at least insofar as having it be one that Kiya spearheaded. In a 1987 interview, Kiya told Beep Magazine that, “I think the monsters you fight and the location of chests should be completely predetermined. RPGs are games where you make the decisions, right? So I’ve always thought there was something weird about randomized battles, fighting enemies you can’t see, whether you want to or not.” What had changed by 1989? In The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers, Vol. 3, Kiya says about that very thing that, “Basically, I just didn’t want to do the same thing every time; I wanted to try something utterly different with each new project… As far as why I went back to the traditional concept of a Japanese RPG, it was because I had not made anything like that yet.” Enix and Sega and Square were finding success with turn-based RPGs, so Kiya decided it was time for Falcom to show that they could pull this off as well since they hadn’t done so yet. And he wasn’t wrong!

Much of what you will do in The Legend of Heroes is fight random battles — or, when inside of a cave or a dungeon, the battles won’t be random since the location of all enemies are revealed indoors, but you’ll still be doing a ton of fighting there even if your goal is to avoid those engagements. If you’ve played any of the other games mentioned here, you know what you’re in for: the game is about progressing so you can experience more of the story and see new locations, but you can’t progress unless you equip the gear and gain the strength to defeat the game’s bosses, and you can’t afford that equipment or gain those levels without a bit of level grinding. RPGs were still a fledgling genre in 1989, and the need for constant leveling and gold earning was the reliable way to extend a game’s length. The Legend of Heroes is no exception.

One item worth pointing out is that, once you complete a game’s chapter, all of the enemies vanish from that part of the world. So, if you want to return to any cave or dungeon or explore the overworld without interruption, this would be the time to do so. There are also items that let you reveal the presence of the hidden enemies you “randomly” encounter — they’re all just invisible sprites running around until you bump into each other — if you don’t want to wait that long but do want to avoid combat. Kiya might have decided to introduce random battles, but he refused to commit fully without some innovations, which is very much like Dragon Slayer. And you also get access to a fast-travel system pretty early on: for all the grinding that exists in this game, it does try to respect your time, which is how it can manage to clock in at around a dozen hours yet still feel like a full RPG experience.

The Legend of Heroes begins with a cinematic that explains to you the history of the world you find yourself in: the last king was killed in a battle against a horde of demons, and the protagonist of The Legend of Heroes, Logan, is too young to inherit the throne. So, his uncle instead becomes the regent, and Logan is sent off to a village elsewhere to study and practice for his eventual reign, except it turns out that his uncle is the one who sent the demon horde against his own brother in order to usurp the throne, and you find this out shortly after monsters come and kill everyone Logan grew up with as he escapes the village. I can tell you all of that without it being a big spoiler for the story, because this seriously all happens very early in the story: the first chapter is about the revolution that will overthrow the regent, and he is barely bothered by its success, since this was just step one for a much larger plan. You then spend the rest of the game chasing down Logan’s uncle — and the mysterious, demonic forces he works for — until finally saving the world. Or dooming it, depending on your interpretation of how things play out at the end.

It’s not quite Final Fantasy IV in terms of its narrative, but why would it be? That game released two years after this one first did, and was a landmark achievement in storytelling in video games. The Legend of Heroes, though, still manages to be a story that involves itself as more than just a little set dressing in the game, and it does a fine enough job of it to make you want to play the rise-and-grind style of the time. It is worth pointing out that Hudson’s localization is far ahead of anything that Square was putting out, both before and for some time after this: everything feels far more natural and less forced, even when the game occasionally slips into ye olde fantasy talk.

More impressive than the story itself is how it’s told. The Legend of Heroes has voice acting. In 1991/92! And not just a little bit, either. Standard conversations with townspeople and what have you are all occurring through text, but the party actually talks, out loud, to each other, as do the game’s major foes. It is… not good voice acting, though. It’s actually pretty bad, both tonally and in its execution, but these were also problems of the time. You know how old Square games didn’t bother to tell you which character was actually speaking, but you could at least infer it through their movements on screen? The Legend of Heroes freezes everyone on screen in order to deliver spoken lines with no names attached to them, so you have to remember what each voice sounds like. Easy enough with Sonia, the lone woman in your four-person party, but the other three voices all blend together just a little too much to make that a simple task overall. If only the game deployed the large-scale character portraits of later Ys titles on the PC Engine CD, so you’d always know who was speaking, but alas.

Here’s the good news, though: you can shut off the voice acting. The only dialogue you’ll be forced to hear is the speech the last boss gives you before the final battle, but otherwise, everything will just show up on-screen as text instead. It would have been nice if the game allowed for both the text and the voice acting to show up at the same time — the voice acting itself wouldn’t have been any better, but it would have been more tolerable if you weren’t trying to figure out who is speaking at any given time — but still, not having to hear those voices for 12 hours is a positive I will not deny.

Customization is actually at the heart of what makes The Legend of Heroes stand out. There are all those auto-battle options I mentioned, plus the ability to speed up messages and shut off the voice acting. You can, however, also build your party basically from the ground up the way you want to through customization. You have the choice of letting the game auto-level your party members for you, or you can shut that off and distribute all of those points yourself — which you absolutely should. That way, if you have someone you don’t want to use any magic, no points will go into Intelligence, which will keep them from growing in a direction that would give them more and more magic points at the expense of some other growth. Want someone to be all high hit points and speed? Focus on increasing their strength and speed. Want them to be a balanced battle mage type? Spread those stats around to both strength and intelligence. Or maybe you want them to have an extremely high crit rate: spend those points in luck.

Every character can also learn any spell: all they need is enough MP to cast it, and for you to have found the sage to teach you. So, you can just pour intelligence points into a character you want to be both your white and black mage, as it were, and then give them whichever spells you want most, likely a blend of status effects and buffs and attack and curative, and go wild. You can also attach healing and revival and warping spells to characters who otherwise are never going to cast anything, so you can save the points of your primary spell user for the moments you really need them. It’s a level of customization that’s honestly shocking for a turn-based game that initially released in 1989: it still seems pretty ahead of the time for the genre in 1992! But again, this is part of what makes it Dragon Slayer: consider how much customization already existed in 1985’s Xanadu.

The only real downside to it is that magic attacks are kind of pointless for much of the game, and you’re often better off with physical attacks. The MP cost is just too high most of the time, and with a few exceptions, most enemies go down easily via physical attacks so long as you’re continually upgrading your gear. It’s still vital to have some magic around, though, especially the spell that allows you to disable all spell usage for both allies and enemies alike — it even works on bosses! And sometimes casting that spell is basically necessary, as some major bosses can stack turns and come at you with life-leeching spells and also giant fireballs that will burn non-resistant armors. Just don’t forget to buy healing items, because again, your spells are impacted by this valve shutoff, too.

On the less terrifying but still fun side of things, you can also choose which version of the soundtrack you want to listen to. There is the programmable sound chip (PSG) version of the soundtrack, with all the Video Game Music sounds you expect from something released in 1992, but there is also the version of the soundtrack that takes advantage of the CD-ROM format, and utilizes the standard Red Book Audio for an arranged version of the original soundtrack.

The overworld theme is always the same and is a CD-ROM track, but otherwise? If you want to listen to the PSG version of things that leans on the standard Turbografx sound hardware, you can! And you can switch back and forth whenever: the music will change to your selection once you enter a new location. Here’s the standard Battle theme, first in its PSG form…

…and then in its CD form:

Regardless of your preference, it’s Falcom Sound Team either way, which means what you’re hearing is the good shit. Sometimes it’s hard to believe there was RPG music out there in 1992 that sounded like this, but that’s the beauty of the CD-ROM format.

It’s really a great soundtrack, and the Battle theme — either version — helps a lot with the incessant fighting. Not enough to save it for you if you don’t have the stomach for a very 1989 way of doing things, no, but still.

What also makes The Legend of Heroes stand out a bit from its contemporaries is the way it blended fantasy and sci-fi. It’s more Final Fantasy than Phantasy Star in this regard: in the original Phantasy Star (and its sequel), you’re playing in a very futuristic world, digging into its more fantasy-esque past, whereas the world of The Legend of Heroes works with the opposite premise: the advanced civilization is already gone, and you are occasionally picking through its remnants. Final Fantasy actually hadn’t gotten to the “hey let’s go to the moon and fight alien demons” phase by the time Dragon Slayer VI had initially released in Japan, and even SNK’s Crystalis was a few months away from its own spin on how robots like the taste of sword.

That being said, it’s all more hints than it is overt in The Legend of Heroes. There is a tower that requires security key cards, and an archaeologist obsessed with the advanced past, but the vast majority of the game is very much fantasy-based with little hints that there is more to it until late in the game. Even your eventual “airship” is a dragon, and not like, a robot dragon or anything. “Just” a plain old dragon, whom you do not need to slay. Even this little bit does work as a runway for The Legend of Heroes II, though, the premise of which is “hey there are some guys in spacesuits outside the castle, what’s that about?” And certainly helps make the modern-day Trails’ blending of magic with science and technology fit in with the larger series.

I don’t know if I’d go so far as to say that Dragon Slayer: The Legend of Heroes is a required play for casual fans of RPGs. If you’re someone who still finds enjoyment from these pretty early examples from the genre, though — someone who was excited about the recent updates of classic Final Fantasies beyond just IV, V, and VI, who enjoys Phantasy Star for more reasons than just IV, who is still perfectly content with old-school Dragon Quest games — then you should find the time to experience a game that might as well have been a Japanese exclusive, given its lack of footprint elsewhere. That’s obviously changed for the series in the decades since, but this is where it all began, even if the initial result was just more and more legends of heroes in Japan for most of that time.

This piece was published in its original form at Retro XP in May of 2022. It has been updated here for Dragon Slayer’s anniversary, and republished to account for research that’s occurred since that time. The original has been updated to reflect these changes, as well.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.