40 years of Dragon Slayer

Dragon Slayer was the game, and series, that launched Nihon Falcom to the kind of success that has them still making role-playing games played worldwide, 40 years on.

September marks 40 years of Nihon Falcom’s Dragon Slayer series, which had its original run ended with creator Yoshio Kiya’s exit from the company, but continues to exist to this day through subseries and spin-offs. Throughout the month, I’ll be covering Dragon Slayer games, the growth of the series, officially and unofficially, on a worldwide scale, and the legacy of Falcom’s contribution to role-playing games. Previous entries in the series can be found through this link.

When role-playing games began development in Japan, their ascent was rapid. That goes for RPGs as a whole, but it’s especially true of the action RPG. In 1983, “action RPG” was not a thing that even existed. Yoshio Kiya, a freelancer programming and designing games for Nihon Falcom as a side gig to his job as an auto mechanic, was one of the key people inventing that subgenre on the spot, with the first real inkling that something new was developing in the industry in the form of Panorama Toh. This is one that’s up for debate for some as a role-playing game, since it doesn’t feature stats or character growth, but it did feature a very early form of the kind of combat that would be fully realized in later Kiya and Falcom titles, in a way that was unmistakably “action RPG," starting with 1984’s Dragon Slayer.

Per Kiya himself, by way of The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers, Vol. 3, he wasn’t selling the games to Falcom so much as showing up with finished ones and trading them and the rights for them in for new computer hardware: Nihon Falcom, before it was a game studio and publisher, was a computer store, selling computers, and it did a little of both for a few years until it finally took off in the field it remains in to this day. Dragon Slayer marked something new and different for Kiya and for Falcom, though: it was the game that, once completed, got him to quit his job in automotive repair and switch to game development full-time, with Falcom hiring him on in a more official capacity. Dragon Slayer was simply the first of many loosely connected games, where the only thing that seemed to matter for the longest time was whether or not there was an evil dragon to be slain by a hero or heroes, preferably using a legendary sword named for the series itself, and in some kind of action RPG.

Panorama Toh might not play like what we consider a role-playing game to be these four decades later, but it was very much based on existing computer RPGs Wizardry and Ultima — the seemingly always modest Kiya, in an interview with BEEP! Magazine in 1987, went so far as to say he was “ripping off Ultima” with Panorama Toh, even. And, like with id’s Hovertank and Catacomb 3D leading to Wolfenstein 3D and then DOOM, which itself led to the explosion of first-person shooters as a defined genre, Panorama Toh is an important step on the road to Dragon Slayer and Xanadu. Which means its existence was also key to games made by other developers at Falcom, like Ys, and by other studios, such as Nintendo’s action-adventure outing The Legend of Zelda: this game, too, doesn’t feature stats in the way we think of role-playing games doing in the present, but you will find those out there who say Zelda is an action RPG as well. Not random folks, either, but the likes of Jeremy Parish, who see the original The Legend of Zelda as the gateway to the genre for the world given its worldwide release and success, thanks to it doing away with some of the “opaque” and “hostile” design decisions of games that, to be fair, he still said, “possessed a certain compelling quality that drove players to unlock their mysteries.” And hey, Zelda’s first sequel, like Falcom did with Dragon Slayer titles, ended up marrying together multiple viewpoints and side-scrolling action in those late-80s days of innovation.

Dragon Slayer released in 1984, the year after Panorama Toh, and it was markedly different from the start. This was in part due to a jump in the hardware and code that Kiya used to make it: Panorama Toh was developed in BASIC, and Kiya attributed its “problems” to “limitations of BASIC.” There were additional puzzle elements in Dragon Slayer, a significant emphasis on items and statistics and leveling up, and combat itself leveled up. Dragon Slayer utilized a very early form of bump combat, much like two of its equally important cousins from 1984: Namco’s arcade smash hit, The Tower of Druaga, and T&E Soft’s personal computer and Famicom success, Hydlide. No one of these games is “more” responsible for action RPGs than the other, as it took all three of them to launch what we think of as that genre, and the adjacent action-adventure one. And they did so in the span of about seven months, with Druaga releasing in arcades in June, Dragon Slayer on the PC-8801 in September, and Hydlide on the PC-8801 and PC-6001 on the same date in December.

All three utilized bump combat. Druaga had you unsheathe your sword before you could cause damage, while using a shield to defend yourself in whatever direction it was facing. Hydlide used the shield mechanic as well, forcing you to hold down a button in order to attack while bumping, and was set up so that you could cause far more damage without taking damage yourself by attacking from the side or back. Health recovery while standing still was also implemented here, which would be used in Ys essentially the way it was here later on, and in games like Xanadu: Dragon Slayer II, as well, although there, health recovery was tied to consuming food; eating to avoid starving during your adventure was pulled from Panorama Toh, and ended up becoming a central mechanic in Hydlide 3, to boot, which also included a day/night cycle. Everyone was borrowing from and building on everyone else, which is part of why the genre erupted in the way it did following this seismic shift in 1984. Competition, yes, and a desire to perfect the vision all of these developers had begun working on years earlier, as technology and budgets allowed.

Dragon Slayer, as said, utilized bump combat, but you didn’t need to hold down a button to attack. Instead, the emphasis here was on learning when to engage in battle, and when to avoid it. It was something of a puzzle unto itself: enemies you simply could not defeat in your current form would spawn, if you defeated enough enemies that you could handle, so battle wasn’t something you partook in as some epic struggle to finally overcome the odds. No, what you had to do was know when it was time to battle to gain experience points, and when it was time to instead go exploring in order to find items to strengthen yourself for the combat that would gain you those experience points.

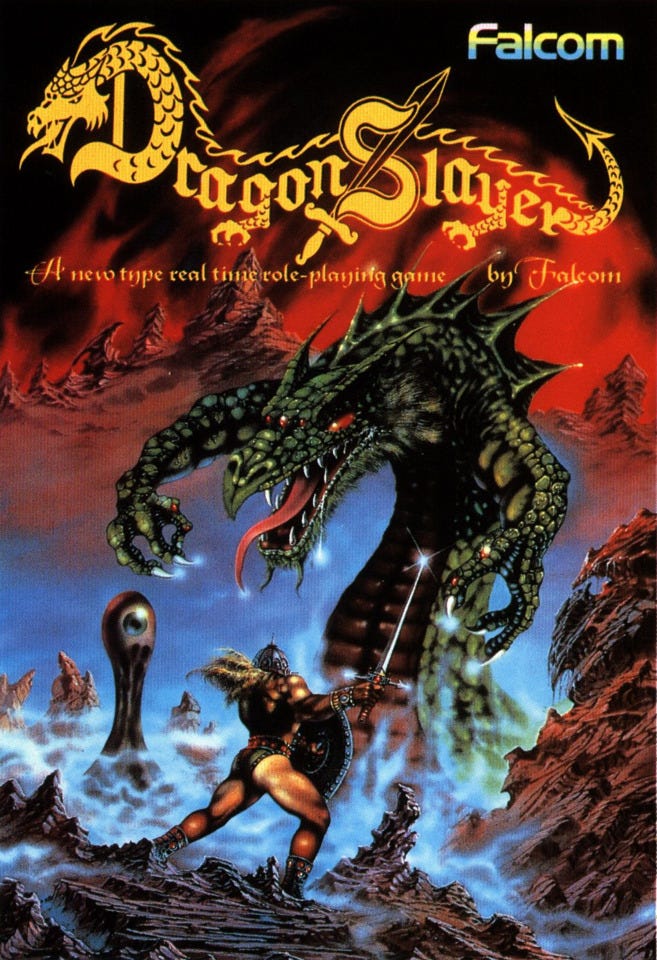

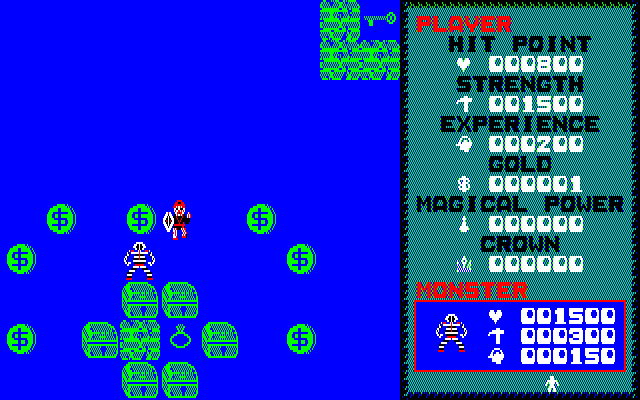

The combat almost feels turn-based given its speed, or lack thereof. You attack once, then enemies attack. The difference between Dragon Slayer and something like a Mystery Dungeon title, though, is that if you decide not to keep bumping into an enemy, they’re not going to wait for you. They’ll just keep attacking until you die. Like the box says, it’s “a new type [of] real time role-playing game,” with emphasis on “real time”. You’ll start to feel the rhythm of a “turn” with practice, and learn in a hurry that you never want more than one enemy engaged with you at a time, especially since you can’t escape by moving diagonally for quite some time. Here’s how combat works: the damage you can do is determined by your strength minus the experience level of the enemy you’re facing. So, to raise your strength, you need to collect power stones scattered across the map and found inside treasure chests, then bring them back to your house, which, in what would end up being very Dragon Slayer-fashion, is contained within this big dungeon, yes.

When your strength is high enough, you can crush these enemies who, prior to this powering up, would have wiped the floor with you and your 1,000 hit points in literal seconds. When you’ve defeated enough of what we’ll call level one enemies, level two enemies begin to emerge from the tombstones that are used as spawn points to replenish the monsters’ numbers in the maze. Which means you then need to go and collect more power stones and bring them back to your house to repeat the process. Defeating these monsters gets you experience points, which increase your maximum health and grant you the use of new spells. You don’t gain levels, necessarily, but going back to your home will refill your health to however many experience points you have, while the new spells are basically necessary for defeating late-game foes. Such as the green monkeys that, if they attack you, can steal your strength, making it so that it’s now essentially impossible to kill them or anyone else the spawn points are spitting out at that point. If you use a spell that freezes the enemies it touches in ice, or the flash spell that stuns every on-screen monster for a few seconds, though, you can get the upper hand on these foes, taking them down before they can make you regret instantaneously losing an hour of “level” grinding.

And hey, once you’ve defeated a few of those green monkeys, they stop spawning, too, so the next horrible threat can make its way into the game. At least those guys are just super strong, though, and not undoing your progress by bumping into you.

If the idea of trudging back to your house to power up sounds annoying, you don’t need to worry. Dragon Slayer has a system for that, one that actually changes the entire game and how you should both view it and interact with it. You see, Dragon Slayer is loaded with items that, broadly, change how you can interact with the world. Want to explore this interlocking, looping maze without fear of taking damage? Equip the cross, which keeps you from being able to attack, but also keeps enemies from attacking you. Want to open up chests? Carry a key around: it can be used again and again without you losing it. Jars that you collect allow you to cast spells, one for each jar you’ve amassed — magic power, like strength, can be stolen by certain enemies, too, so keep an eye on how many uses you have before you commit to solving problems with spells. Coins grant you an additional 500 hit points above the maximum allowed by your experience total, once you bring them back to your house. Oh, and if you wear a magic ring, you can actually pick up the very bricks that comprise the labyrinth and rearrange it. For the purposes of the magic ring, your house? It’s a brick, and you can push it around wherever you go, so long as you have a magic ring. Meaning, you can bring the house to the large collection of power stones you found in a room that was previously full of unopened treasure chests, before you got in there with a key, rather than lugging each stone back, one at a time, to the house.

Yes, one at a time. You don’t have an inventory in Dragon Slayer. You’ve got two hands, and one of them has a sword in it. Once you find a sword, anyway. Want to open that treasure chest? Go pick up a key, but while you have that key in your hands, you can’t collect coins, or magic jars, or pick up the cross or the magic ring or anything else. Drop the key first, then pick up those coins or jars, then pick the key back up, but you can’t have both a key and a magic ring, or a ring and a cross, and so on. It works that way for every item type, which means you need to carefully consider just what it is that you’re going to be doing in that moment, and then go do it, while remembering not just how you got to where you are and how to get back to where you were, but also, what items you picked up and dropped along the way. Oh, and there’s a ghost that will, every now and again, fly across the screen attempting to steal what’s in your hand or pick up loose items on the ground. Not to make them vanish, but to drop them somewhere else in the labyrinth.

Before you react poorly to either of those bits of news, they’re both very manageable issues. You know you have a limited inventory, but you also learn to work around it, and while the labyrinth was massive by 1984’s standards, in 2024, you’ll sort that all out with a map in your head in no time. (Or even just use the map spell if you must, to see what’s around and if any landmarks or recognizable shapes are nearby you.) And your house heals you whenever you go back to it, or adds to your hit points for all the coins you collect, which means things like, say, parking your home underneath the dragon you’ve set out to slay, so that, after inflicting as much damage as you can without dying to one of the heads of said dragon, you can go refill your health and then come back for more slayage-in-progress. Solutions exist for every problem, for those willing to seek out those solutions.

You can quit on Dragon Slayer because it’s not all laid out for you, because it’s a game that starts you out without a sword (yet another thing it has in common with roguelikes, really), with no explanation of what you’re supposed to do since it’s all in the Japanese manual, and then expects you to trial-and-error your way through its idiosyncrasies until you’ve slain that dragon. Or, you can realize all the tools you need are right there, in-game, and start figuring out which one is best-suited for what task. Again, this is a game where a magic ring lets you pick up your house and move it around a dungeon, and that ring also lets you push the walls of the dungeon to make new doors and paths for you. Put your mind to it, and you can clear Dragon Slayer in an hour, which is not really enough time to feel like grinding is this eternal thing you’re doing. It’s an hour! You spend more time thinking about how you need to stop mindlessly scrolling on your phone than that. At least you get to cut the heads off of a dragon at the end of this “mindless” activity.

Well, you can clear the first phase of Dragon Slayer in an hour. When you defeat the dragon, four crowns appear on the map, each of which has to be collected and brought back to your house. You should know that monsters have taken a very sudden and real interest in your house at this point, and even if you left it right under that dragon during the fight, it’s now back where it first resided, making you work for this resolution. Once all four crowns have been brought back to your home, you warp to a new map, where the dragon lives once more, and you start the process of learning the shape of the labyrinth and solving for it once again. It’s very arcade game, in this sense, despite being so obviously a Japanese computer game of its era. You’ve completed it, yes, but not really: if you want to keep going for a while yet, you can. The Tower of Druaga, just months earlier, had introduced the idea of an arcade game having a true ending and resolution to its narrative: Dragon Slayer would have to wait for its sequel, Xanadu, to have a more clear-cut ending and narrative to follow.

Everything described here is true of the second version of Dragon Slayer, which added various improvements to the original 1984 release of the game — difficulty re-balancing, music, sound effects, improved graphics — and ended up being the base from which future ports were built. That includes the Sega Saturn’s remake of Dragon Slayer, found on the Japan-only Falcom Classics release. This is the definitive edition of Dragon Slayer to this day, and luckily, you don’t need to be able to read Japanese to be able to play it. Or any version of Dragon Slayer, really, since all the vital information is displayed in English even in these Japan-only releases, but since the Saturn version is the ideal edition, it’s the one you should seek out.

Falcom Classics includes Dragon Slayer, Xanadu: Dragon Slayer II, and Ys: Ancient Ys Vanished, which is the first part of the original connected Ys duology, each enhanced graphically and with two different modes: the rule sets for the games found on their classic releases, and then a new “Saturn” mode which institutes some additional balancing to gameplay. For Dragon Slayer, that means putting a few key items right in front of your home from the start, so you can begin experimenting and maybe not die a bunch of times looking for a weapon. A sword is there, as is a power stone, so you can pick that up and, hopefully, bring it to your house to see what it does. Learning that it increases your strength should set you on your way to go find more of those little blue rocks. Fast-forward an hour ahead, and you can rightly call yourself a dragon slayer. The graphical enhancements aren’t quite to the level of what would become Ys I & II Chronicles for Windows just a few years later, but the difference between the PC-88 original from 1984 and 1997’s take on the same game is both stunning and obvious.

Notice how, in the image on the right, the warrior you’re controlling looks an awful lot like the one that’s featured on the box art for the PC-88 release of the game? It took 13 years, but Falcom got there. The protagonist in the PC-88 edition of the game looked a little more like an evil clown you had to kill before it killed you, but hey. That was what was possible with the tech in the day in that moment: try to remember what early NES games looked like compared to later ones, and you’ll understand why early PC-88 games looked like that but later ones were such an improvement despite the hardware being the same as it was when it first launched.

Dragon Slayer is old, in pretty much every sense of the word. It predates Zelda. It released a year after the Famicom. The hardware it launched on, the PC-88, feels ancient: it was two years and change old when Dragon Slayer released for it. It’s part of a “trilogy” of early action RPGs from such a different time period that two of them never even made it out of Japan until, in the case of Druaga, decades later, and the other actually has yet to: D4 skipped right over Dragon Slayer and went right to its sequel, Xanadu, and that game’s expansion, on its EggConsole service for Japanese personal computer games on the Switch. Hydlide, the only one of them to see a release in the 80s, was derided for seeming light years behind even then, owing to it coming out in North America after the games it had influenced in the first place already had. It’s not quite as severe as Space Invaders existing outside the history it helped create, but it’s about as close as you can get, and certainly the action RPG equivalent.

And yet! And yet. Like Parish said years ago, there’s something here in games like Dragon Slayer that captured the minds and attention of gamers in 1984. Something compelling them to solve the game’s mysteries, to uncover its secrets, to slay that dragon; something to prepare them for what was to come, like the landscape-altering, record-setting Xanadu. You can find what that was, too, if you’d give yourself and Dragon Slayer the time to discover as much, and better understand a different period of gaming — one that directly led to the one you enjoy in the present — in the process. Yet another thing that Dragon Slayer has in common with Druaga.

The legacy of Dragon Slayer is far less opaque than its gameplay. It is, arguably, the first action RPG, or at least the first to truly embrace that designation: Masonobu Endō redesigned a Druaga prototype to have more action and less role-playing elements in it, which is how we ended up with the game we did. Its use of items to figure out various puzzles, of an open-world that was itself a labyrinth and dungeon to be explored and solved, its action-focused combat, would all be utilized in The Legend of Zelda. It also, most importantly for our purposes, was the start of the Dragon Slayer series, which, for the most part, are action RPGs that all took a different approach to what that term even meant and could mean, further expanding the genre and video games in a way that continues to resonate in the present. Ys was meant to be for those that didn’t want as hardcore of an action RPG experience as what Dragon Slayer created, which tells you right there what Dragon Slayer was all about. Systems that challenged, both genre conventions and the people who would play the games.

Xanadu: Dragon Slayer II followed. Then there was Romancia, a side-scrolling action RPG designed for you to interact with loads of NPCs, follow directions, complete quests, and do all of that in a 30-minute time limit. You would learn, fail, learn some more, and apply all of your knowledge until you could complete it in one short go. What North America knows as Legacy of the Wizard is actually Dragon Slayer IV: Drasle Family. Dragon Slayer V is Sorcerian, which, like Legacy of the Wizard, did receive an international release, through Sierra and MS-DOS. Dragon Slayer VI? That just happened to kick off the series we know today as The Legend of Heroes, which, along with Ys, is Falcom’s most successful and popular series, with games for it still being made over three decades later; it felt very much like Yoshio Kiya declaring that he could make a Dragon Quest-style RPG if he wanted to. Dragon Slayer VII was actually an early real-time strategy game known as Lord Monarch, as Kiya and Falcom continued to veer off the action RPG path with Dragon Slayer, before returning to it with The Legend of Xanadu, a spin-off of Xanadu that utilized the kind of depth featured in its namesake, but with combat inspired by Ys, and a world much larger than either of its inspirations had inhabited to that point.

This month, we’ll celebrate 40 years of Dragon Slayer, by looking at almost all of the above, as well as some of the later-day spin-offs of the Dragon Slayer series. Given so much of Dragon Slayer still has yet to make it outside of Japan in an official capacity, there will also be a look at the series and unofficial translation work that’s made it accessible for the people willing to go outside those official channels to experience everything Dragon Slayer — and the translation work that still remains to be done. Yoshio Kiya’s unhappy exit and the transformation of Falcom over the years will certainly come up. And, of course, a feature on The Legend of Heroes: its creation, its evolution, its ambition, and how it became Falcom’s most significant international hit.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

Does this mean a feature on the WAY out there spin-off and a top 5 NES game ever, Faxanadu, is in the pipes? 👀