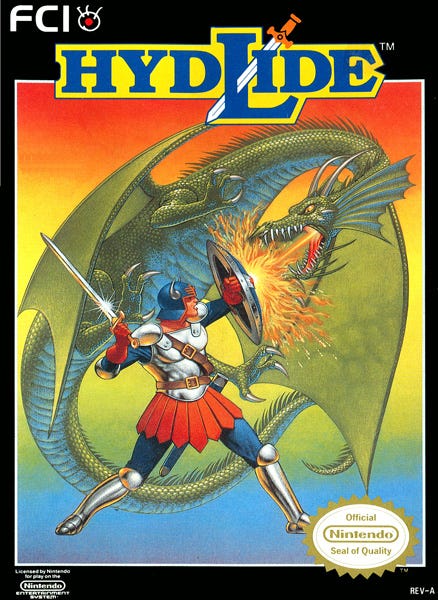

It's new to me: Hydlide

Hydlide might have been derided when it arrived on the NES, but it's a vital game in the history of action RPGs.

This column is “It’s new to me,” in which I’ll play a game I’ve never played before — of which there are still many despite my habits — and then write up my thoughts on the title, hopefully while doing existing fans justice. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

When Dragon Quest released in North America (as Dragon Warrior, due to copyright issues), it was three whole years after it had become a series-spawning sensation in Japan. The video games of 1989 were significantly different than those of 1986, so, Nintendo of America did more than just localize the game for its release in their territory. The graphics were updated so they would be more in line with the expectations of the day, and a battery backup save feature was introduced, rather than the password system the Famicom release relied on. While Dragon Warrior wasn’t the hit on the NES that it was on the Famicom, it still released in a form where it could pretty easily be the start of a love affair with the console role-playing game for the right person, and it did well enough for the subsequent NES series entries to also see a North American release. Dragon Quest is rightly remembered as one of the most important and influential games ever, and worth going back to for more reasons than just its key place in history.

Hydlide, similarly, is one of the key entries in the early years of the action RPG. It was highly influential, right there alongside Nihon Falcom’s Dragon Slayer in the shaping of what action RPGs were and could be. It’s not widely remembered or heralded the way Dragon Quest is for a number of reasons, but one of the easiest to identify is how its introduction to North America and the NES went. Basically, the opposite of how Dragon Quest’s did. Hydlide originally released on the Japanese computer systems, the PC-6001 and PC-8801, in December of 1984, then more Japanese PCs like the MSX, FM-7, MSX2, and PC-9801 over the course of the following year. In 1986, Hydlide Special released for the Famicom, which updated some gameplay elements to improve on the original, like introducing a high speed mode to cut down on how long it takes to level grind, that developer T&E Soft had first utilized in the game’s 1985 sequel, Hydlide II: Shine of Darkness.

Hydlide and its Famicom Special variant would sell two million copies across Japan. To give you a real sense of how significant that figure was, the original Dragon Quest moved three million Famicom and NES copies combined between Japan and the United States. Ys, Falcom’s own action RPG series that persists to this day and gets a ton of credit for pushing the genre forward, would borrow heavily from elements of Hydlide for its first entries. And yes, it would create a better experience than what Hydlide had managed, but Ys was able to stand on the shoulders of giants and all that, whereas Hydlide was “merely” one of the giants in question.

When Hydlide was released in North America for the first time — also in 1989, also three years after its Famicom release just like Dragon Quest — it received no real updates. It still looked exactly like it did in 1985, which is to say, like an NES game from 1985. The limited, temporary save file system which only worked so long as the NES’ power was on remained, not replaced by a full-on battery backup, with passwords being the true keeper of progress. The gameplay, which had been so groundbreaking back in 1984 on the PC-8801, was no longer that. The Legend of Zelda, while not an action RPG like Hydlide, was still a fantasy-based action-adventure title, and because of that North Americans had a certain expectation for the look and feel and gameplay systems of a game where you strap on a sword and start attacking monsters. Two games, both heavily influenced by Namco’s The Tower of Druaga (Hydlide, per The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers Volume 2), and both going about showing off that influence in differing ways. The Legend of Zelda landed in North America first, and, unsurprisingly, the action-adventure genre (you know, “Zelda clones”) flourished there in a way bump combat action RPGs, introduced later and less effectively, did not.

You are extremely weak throughout Hydlide. You can level up, but you will die quite a bit doing so, and even when you have leveled, you still run the risk of dying often. You’ve got to remember that Dragon Slayer and Hydlide were both inventing their genre in 1984: the tweaking and balancing of systems and all that was still to come for action RPGs. So, at first, you’ve got some brutally difficult games that require a ton of patience — patience that was easier to come by in ‘84 than in ‘89. That patience, though, had an instant reward: Hydlide was the first game to utilize a health regeneration mechanic. Standing still for a bit would allow your limited hit points to recover, so figuring out where to stand and be safe before going back on the attack becomes vital in a hurry. Ys, notably, would use the same mechanic, and even repeat Hydlide’s setup where your health could not be recovered in a dungeon or cave, only out in a field. Hydlide, though, was even more restrictive about it: you can’t be standing on a forest tile and recover your health, either, even if it’s right there next to a field!

While you’re always on the attack in Ys, with Adol’s shields simply reducing incoming damage, Hydlide is a little more Druaga-like in its approach. Your shields reduce incoming damage, and some even block some damage types entirely, but you don’t attack while your shield is up, which is the default as you walk around. To attack, you must hold down the A button, which reduces your defensive capabilities but allows you to attack with your full might — The Tower of Druaga similarly made you choose between offense and defense by having Gil swing his shield out to the side when his sword was unsheathed. In Hydlide, however, where you attack an enemy from matters, too, even more so than it does in Ys’ own bump combat titles. Come at foes from behind or from the side they’re not walking toward, and you’ll damage them without taking damage. Meet an enemy head-on, however, and you’ll inflict damage, but take some yourself, too. Against weak enemies, this can still sneak up on you and kill you, and against powerful ones, you’ll be dead before you really know what happened. You have to watch for movement patterns and anticipate where enemies are going, then come at them from where they aren’t looking. Your first spell, Turn, forces nearby enemies to start walking back in the direction they came from, so that you can sneak up behind them and attack. It’s vital, especially early on, when you’ve got to take out enemies like the Vampire who will defeat you almost instantaneously otherwise.

Your spells, by the way, require a certain minimum amount of magic remaining in your pool, otherwise you can’t cast them. This automatically refills over time, so you do need to be strategic about casting, and you can’t just spam fireballs or what have you early on because of this.

You have to grind for experience in Hydlide in order to have enough strength (and hit points) to defeat higher-level monsters, but you also can’t just grind forever against lower-level foes to get it. You only receive experience points from monsters the same level as you or higher: once you’ve exceeded their level, you’ll receive zero experience from them. Not one point, like in Ys, but none. So, when the slimes and kobolds in the opening screens aren’t giving you experience points anymore, you know it’s time to move on and figure out what’s next.

And figuring out what’s next, well… you’re probably going to need a guide for that. Hydlide isn’t so free with the hints about what to do. You get the opening to the game, where an evil sorcerer’s evil dragon turns a princess into three fairies who scatter across the land, and then you — playing as a knight named Jim, which you know because it says so in the manual — are just kind of sent off to presumably retrieve them and defeat the person responsible for this. Dragon Quest might have overdone it with the Elizabethan English localization, but at least you always knew generally about what direction you should head in and where you should be going next and aiming to do because of all that wordiness. Hydlide is open world, and without The Legend of Zelda’s helpful old dudes around to reorient you as necessary. Action-adventure games from the era like Zelda and Golvellius would be sure to let you know that you should be poking around certain areas until you find what you’re looking for, but Hydlide was from a time where, if a fairy was hidden in a tree in a field where the rest of the trees were full of wasps that would kill you if they sting you enough, well… you’re only going to find that fairy by accident or sheer luck unless you look it up or someone tells you to keep shaking those trees, wasps or no.

You’ll spend your time in Hydlide exploring, fighting, recovering health, and trying not to die as you look for items that you then try to figure out the use for. You stumble upon a golden cross one screen over from your start location, and then a screen over in the opposite direction is the lair of the aforementioned Vampire: pretty easy to figure out that you should have the cross if you want to be able to get near the vampire, yeah? Not everything is as obvious, though, so you’ll spend a lot of time poking around. The thing to remember is that if you’re in an area where your attacks aren’t causing any damage, you’re either missing an item, an upgrade, or simply aren’t supposed to be there yet until you’ve leveled up some more against weaker foes.

Eventually, you recover all three fairies — and if you know what you’re doing, such as in the above video, “eventually” isn’t all that long of a time — and can make your way into Hydlide’s end game, which features a final boss that basically requires that you have picked up the potion that brings you back to life one time after death even if you’ve maxed out your levels and health. It’s not an easy game to play nor to complete, and while you can certainly figure it all out without a guide eventually, like people did in 1984, you have more games and tolerances maybe not in line with the hardy folks who didn’t know any different back then. You can’t put the Zelda or the Ys back in the box once it’s out, you know? That knowledge stays with you, which is why, outside of how Hydlide looked to 1989’s eyes, it just didn’t connect in North America like it had in Japan. Where, by the way, the vastly superior Hydlide 3, which had built on the series’ own past as well as the efforts of others in the same way Falcom and Ys had, was already out on the Famicom and Mega Drive.

It’s a shame that Hydlide didn’t see an update a la Dragon Quest when it reached North America. The game was a revelation in 1984, vital to the development of the action RPG as much as anything Falcom did in the same time period, and wildly popular in Japan. What released in North America five years later, though, was a game that had been mildly adjusted for 1986’s standards, in a fast-moving and growing video game industry. The original Super Mario Bros. released in North America in 1985, and Super Mario Bros. 3 in 1988: think of how much changed between those two releases, and then consider what kind of growth was still to come on the NES in terms of both innovation and visuals in the form of other platformers like Kirby’s Adventure. Hydlide released at the same time as Dragon Quest on both occasions, and just one year later, a marvel like Crystalis would show up on the same system, making Hydlide look even worse by comparison. Hydlide, without getting a makeover in addition to a localization, never stood a chance outside of Japan.

That could change in the present, of course. Falcom has been remaking Ys games, fixing what didn’t work decades ago in some cases and just updating existing classics in others. While T&E Soft, which published and developed Hydlide, no longer exists, D4 Enterprise currently has the rights to their properties. So maybe at some point we can all be treated to the updated version of Hydlide we never received before. That, or you can just play Fairune to get an idea of what Hylide was going for without so much of these original systems in place.

At the least, it’s worth understanding how important Hydlide is to video game history and the development of Japanese video games, even if you never actually play it yourself to see. Think of how much the action RPG genre has grown over the decades, from Ys to Crystalis to Mana to Terranigma and all the way to the present, to the Niers and Souls and Elden Rings — Dragon Slayer and Hydlide paved the road that brought us to those games. And Hydlide even influenced developers you might never think it would have, from Hideo Kojima claiming it and the feelings it elicited in him as an influence on Metal Gear Solid V’s open-world design, to Hideki Kamiya, whose canceled PlatinumGames title, Scalebound, cited Hydlide 3 as an inspiration.

And what if Hydlide had been given some proper touching up? Maybe a second song that took longer to loop, that didn’t just remind you of Indiana Jones and also times where you could be listening to more than one tune over and over again? Maybe video game history goes a bit differently if North America has a better reaction to Hydlide, and it sells far more copies than it did. Publishers take chances on more localizations of action RPGs, maybe Ys gets more of a North American foothold, maybe then Hydlide 3 gets a bit more of a visual makeover when it’s introduced as Super Hydlide to keep it from also being casually dismissed for how it looks… we’ll never really know, since that’s not how things played out. But what is known is that, despite how it might have felt to play Hydlide in 1989 or now, it’s a significant release in the history of video games, Japanese or otherwise.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.