It's new to me: The Blue Crystal Rod

The main line of Namco's Babylonian Castle Saga of groundbreaking role-playing and action games wraps up with something out of left field.

This column is “It’s new to me,” in which I’ll play a game I’ve never played before — of which there are still many despite my habits — and then write up my thoughts on the title, hopefully while doing existing fans justice. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

The Tower of Druaga was a massive hit in Japanese arcades, with influence that impacted the moment in games and continues into the present. An action role-playing dungeon crawler with enough action-adventure elements to inspire the creation of The Legend of Zelda, it spawned three sequels: another arcade release in The Return of Ishtar, a Famicom game, The Quest of Ki, and a Super Famicom original meant to put a bow on the series as a whole, The Blue Crystal Rod.

The Return of Ishtar still focused on dungeon crawling, but with less action and more running away as needed, as well as a co-op element with two very distinct characters to play as: Gil, the sword-wielding hero of the first game, was more of a break glass in case of emergency type here, while Ki, the priestess Gil saved in Druaga, was at the forefront due to her wide variety of magic spells and attacks. Rather than ascending the tower, as you did in the first game, you’re now descending it post-defeat of Druaga. The Quest of Ki was a prequel, which featured Ki ascending the tower in search of the Blue Crystal Rod that Druaga had stolen in the first place — you complete the game by reaching the rod, but Ki is turned to stone at that moment, too, leading directly into Gil’s attempt to rescue her. And The Blue Crystal Rod wraps the whole thing up with Ki and Gil now tasked with putting that magical item back where it belongs, in heaven, per the orders of Ishtar.

Game Studio, founded by Druaga creator Masanobu Endo after that game’s success, developed the three sequels. Endo and Game Studio did not seem interested in sticking to a genre for more than a single game, which is how the third title ended up as a platformer with its own weird physics that was heavily based on the gameplay of the Atari game, Major Havoc. If you thought that was a major departure for a series whose first game can list The Legend of Zelda and Elden Ring as titles it influenced, well. The Blue Crystal Rod is an adventure game.

Not a spin-off adventure game, not Bablylonian Castle Saga Gaiden or anything of the sort. The Blue Crystal Rod is the fourth and final of the mainline Babylonian Castle Saga games, and it’s an adventure game. Gil and Ki have been tasked with bringing the Blue Crystal Rod back to heaven where Druaga stole it from, and oh, no pressure, but humanity cannot ascend to heaven if they fail to do so. Getting to heaven must be easy, right, for a priestess of Ishtar and the famed knight who rescued her and brought the rod back in the first place, yeah? Wrong! You’re going to have conversations in this game, and if the conversations do not go well, or you forget to check in with Ishtar, then you won’t see heaven.

The Blue Crystal Rod features 48 different endings, and which ones you get are based on (1) the places that Gil and Ki travel to or don’t travel to, (2) the conversations they have or don’t have while in those places, (3) the answers they give when asked questions during those conversations, and (4) whether or not they go back to discuss what they’ve learned or gained in their quest with Ishtar, who sent them on it in the first place.

The Fandom wiki for Blue Crystal Rod has a translated sample of how these chains work together to bring you specific endings. Sadly, the original full list of the 48 ending chains seems to be lost now thanks to Yahoo! Japan’s services ending, but at least this snapshot can give you an idea of how it all works (and you can watch video of all 48, too, if you’re capable of reading Japanese).

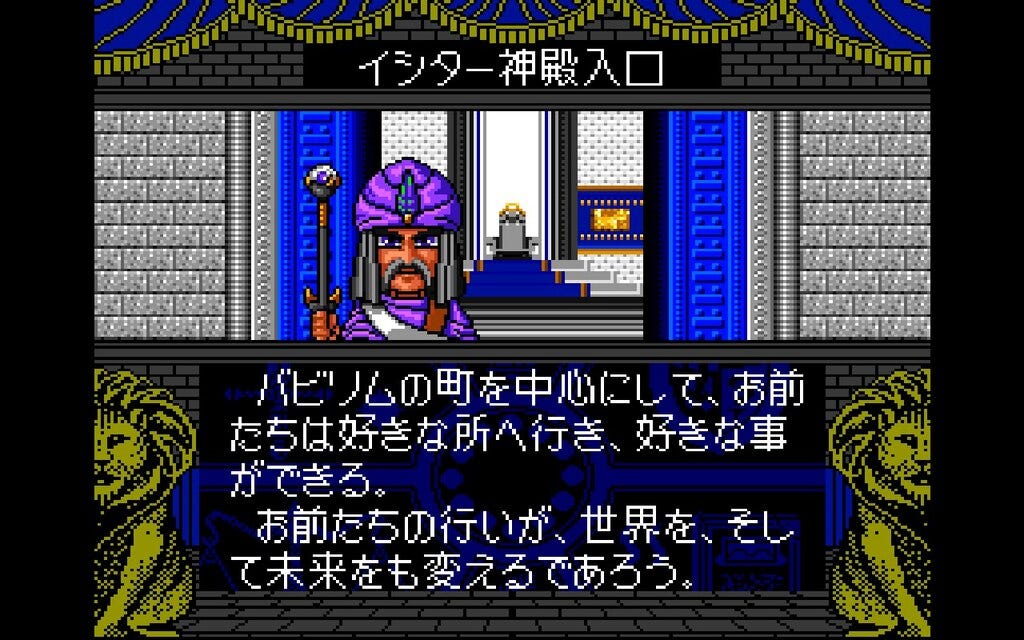

The process begins in the presence of Ishtar, where you have questions to respond yes or no to: you have to answer yes to these initial ones since it involves actually taking up the quest you’ve been tasked with. Then you head out to the Hanging Gardens, and speak to Ishtar to some, and here is where things can branch on you, depending on your answers in the follow-up conversation. You need improved strength, acquired in your travels and through conversation, to go to the Sumer Empire, and then you speak with Ishtar afterward to branch further, which opens up progress in the Underworld or the Stormy Mountain, depending on your response to Ishtar. Your goal is to get to Anu, aka heaven, to put the Blue Crystal Rod back, so you basically want to be answering questions in ways that reflect well on you, and don’t, say, betray the ideals of Gil or Ki.

You’re not given very much information to work with in terms of how you’re actually supposed to find heaven, but that’s the game. You’re supposed to figure it out and prove that humanity should have a seat there when it’s time: it wouldn’t do for Ishtar to just explain it all to you in painstaking detail. So, what you get is a look at a map of the region and the places you can travel to, and a lengthy tutorial if you want it from a guard outside of Ishtar’s throne room, who will explain every detail of how the game works, including what each button does and how to save to the point that he even makes a joke about the R button having a function added late as a surprise by developer Koichi Nakamura. This comes from machine translation, not something more official or trustworthy, but that bit ends with the guard saying, “Irresponsible game designers who introduce new ideas without planning are to blame.”

The guard tells you that your actions “will change the world and the future,” and while the number of actions you can take are pretty limited, he wasn’t lying about the world changing depending on how you handle the situations that do come up. You get chances to increase Gil’s strength (but at what cost?), to travel to the underworld where no living creature has ever returned from since it’s a land for the dead, which allows you to speak with Druaga, the villain who kicked this whole saga off, to go to a neighboring empire, to speak with regular citizens about their problems. There aren’t second chances for anything, either: you’re stuck in the path you set out on, and you’ll get the ending that matches your experience. If you want a different ending, you have to play the game a different way.

One thing the tutorial guard mentions that merits it is that The Blue Crystal Rod is not like a first-person dungeon crawler where you can turn 90 degrees and change directions. You are always facing front here, and are simply moving left, or right, or backward, or forward, while still facing that direction. The game has a child’s understanding of a compass, where up is actually north, left is west, right, is east, and down is south. Given that, it’s kind of an odd system, but you’re just exiting one screen and heading to another rather than traveling in a 3D space, so there’s really no reason to need a more complicated movement pattern that exists in, say, the original Phantasy Star, or Shining in the Darkness. You’re not keeping track of your movements with maps, and even the labyrinth you can go into changes its order, which if anything makes the simple form movement across the game takes welcome.

Certain locations will lock you out based on your previous actions and behavior. As the machine-translated guard put it in the tutorial, “Your previous actions were inappropriate,” and “If you really want to go, make sure you change your behavior.” This is why, for example, answering Yes or No to Ishtar when you visit her again can lock you into one path and out of another. It’s a complicated web that you’ll figure out with some intuition and practice, and while an adventure title on the Super Famicom released in 1994 might not feel as ambitious or as adventurous as the earlier Babylonian Castle Saga works, we’re still talking about a game with 48 endings that will lock you out of potential interactions you need to experience to get certain endings at the drop of a hat. It’s at least still got that punishing spirit the series is known for, and it warns you about it as early as the tutorial, which was not kidding when it said that failure to reach heaven will assure that the world will “remain wrapped in darkness.”

It’s lovely seeing this large-scale art of characters from the Babylonian Castle Saga. The Tower of Druaga was an arcade game made in 1984, featuring cute little sprites. The Return of Ishtar is from a very specific moment in Namco’s history where everything is looking bigger and more impressive, but also a little weird, too, a little off from where art would go: it’s an in-between phase, stylistically. The Quest of Ki had some detailed static art of characters in between stages, and later ports of The Tower of Druaga, most notably the one released on the PC Engine, had much larger, more detailed sprites. But The Blue Crystal Rod, as a 1994 Super Famicom game, understandably has the most detailed and impressive looking ones. They just aren’t ever shown in action, since there isn’t action to be had.

You likely figured this out on your own at this point, but The Blue Crystal Rod was not released into English-speaking territories — none of the other Babylonian Castle Saga games had been by 1994, either, and that wouldn’t change for any of them besides the original for decades after. It also hasn’t seen an unofficial translation, hence the machine translation quotes in this piece: Google Lens/Translate was utilized throughout the game in my attempt to see heaven, which felt like it took only slightly less time than trying to learn Japanese myself would have. Given that, if you actually can read Japanese and know (or can know) the exact wording of these quotes from The Blue Crystal Rod: sorry! But I at least was able to get the general gist of things here, which is what was needed to see how the game works in action instead of just in theory.

There are a number of spin-offs in the Babylonian Castle Saga that would release for nearly 20 years after The Blue Crystal Rod landed on the Super Famicom, but this is the canonical end of the mainline series. Where else is there to go after, “The Blue Crystal Rod has been returned to heaven, and now humanity is allowed to go there, too,” you know? Many of the others are, understandably, set far in the future and with some different characters, with the setting of the universe being the primary connective tissue, or are spin-offs to the point of not being canon in any way. The Nightmare of Druaga, for instance, is just an excuse to crossover with Mystery Dungeon instead of being part of the main series, but that’s fine, it doesn’t have to be anything beyond that. That game rules, good instincts making it happen, everyone.

Game Studio would keep making games after Endo’s Druaga-shaped baby was finally put to bed, and not always with Namco, either. Plenty of these games were ports of existing titles, like Wizardry VI on the Super Famicom, and even more of them were Japan-exclusive titles, but a few ended up with international releases, like the (adorable) Nintendo DS sequel to Ōkami, Ōkamiden. They’re still very much active, too, to the point one of their titles, The Bird in the Cage, has a Fornite collaboration.

The Blue Crystal Rod is the lone one of the original foursome of Babylonian Castle Saga titles to not be legally available somewhere: The Tower of Druaga is in the current Namco Museum release, as well as on Arcade Archives and with its Famicom edition on Namco Museum Archive. The Return of Ishtar is also on Arcade Archives, and The Quest of Ki, while not officially available outside of Japan, is accessible with a Japanese Switch account through the Namcot Collection app as DLC. The Blue Crystal Rod, though, only exists on original hardware. It’d be nice to get an actual translation of it, official or otherwise, to be able to experience it in a much less stop-start way than I was able to, but if you can read Japanese, it’s there waiting for you without the hangups and wait times of machine translation to deal with.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

I applaud putting in the effort to play an untranslated game. Not sure of the standards at the time but 48 endings on an SNES adventure game sounds impressive. It's a shame that it has basically been buried since.