It's new to me: The Need for Speed

The long-running multiplatform series made its debut on the 3DO, as part of EA's efforts to support the new CD-ROM console.

This column is “It’s new to me,” in which I’ll play a game I’ve never played before — of which there are still many despite my habits — and then write up my thoughts on the title, hopefully while doing existing fans justice. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Need For Speed is, at this point, one of EA’s longest running series, younger only than the likes of Madden, Road Rash, and the franchises EA has picked up in acquisitions, like with Origin, which came with Ultima and Wing Commander, Maxis with SimCity, and Bullfrog, which made Populous. Need for Speed didn’t get its start on personal computers or the Playstation in the mid-90s, however, despite that being where most people who have played the original likely know it from. It first launched on the 3DO, a system with an EA affiliation and their full support, way back in 1994.

There, it was known as Road & Track Presents: The Need for Speed, and much of the design was based around you being a speed-obsessed driver, which, depending on how well you performed in the races, was either complimentary, with your opponent in awe of your prowess, or, if you crashed a bunch of times and weren’t very good, you were treated like a danger to everyone around you. Which, fair, driving around at 150 miles per hour on active roadways makes you dangerous even if you’re a fantastic driver. Doing so when you’re incapable of actually controlling your death machine on wheels is something else entirely.

The 3DO Company was founded by Trip Hawkins, who had first founded EA back in 1982 after leaving his position at Apple. Hawkins’ time at EA was the stuff of legend, between coming up with the idea to bring on John Madden as a spokesperson for a football game in the first place, and his partnership with Sega, which was driven by an aggressive idea he had that everyone else disagreed with for understandable reasons. Rather than deal with Nintendo and their strict licensing fees, EA wanted to team up with Sega to combat them in the marketplace and break their stranglehold that allowed them to be the way they were. To do this, Hawkins had a team at EA reverse-engineer the Genesis without actually having the tech on hand, so that EA could then develop unlicensed games for the system and avoid paying licensing fees at all. The real goal was to use this as leverage in talks with Sega, to drop how much of EA’s potential profits on their games had to go to Sega: normally, $8-10 per game cartridge went to Sega, and Hawkins was asking for $2 per cart with a $2 million cap per game.

As Hawkins told ESPN’s Outside the Lines in a Madden retrospective, “"Only two times at EA did everyone in my management team pull me into a room and say, 'We all disagree with you. The first time was about not having private offices. The other time was this." Sega agreed to a deal, though, out of fear that EA would simply sell the secrets of their technology to other companies and tank the entire licensing model in the process. The two ended up working together so closely because of this initial contract that EA even came in to save the day for Sega, who had a Joe Montana license for their own football game but no game in time to cash in on that license for the 1990 holiday season. EA took their Madden knowledge, made an inferior (but not bad!) football game on purpose for Sega, and everyone went home happy.

Which is to say that Hawkins had no qualms about taking big swings: he left an executive position at Apple to bet on video games, specifically, with the founding of EA, went after Madden at a time when that sort of thing didn’t really happen yet, challenged Sega by telling them yeah we’re basically blackmailing you but our lawyers are better than yours, and then decided to leave EA and its third-party ways to pursue the console space. And the 3DO would be different for publishers than every other console: to Hawkins’ credit, he wanted everyone to have a similar experience to what he negotiated for EA with Sega and the Genesis.

The licensing fee for 3DO games was a mere $3 compared to that aforementioned $8-10, and instead of The 3DO Company manufacturing the consoles themselves, they instead would license out its production to various tech companies, and earn money on each console and game sold. The lack of production costs would, in theory, allow them to keep overhead down. Problems arose with the model, though: consoles typically sell at a loss with game sales making up the difference, but since, say, Panasonic wasn’t picking up licensing fees for games purchased for the 3DO systems they produced, they had to make that money back in one place: at retail. The 3DO was the most powerful console in existence at the time of its release in 1993, but it was also priced like that was the case, at $700 in 1993 dollars. Or, the equivalent of $1,527 in 2024, per an inflation calculator.

The high price meant that not many consoles were sold, which in turn meant that there wasn’t a large customer base to buy the games that did come out for the 3DO: publishers loved the idea of a $3 licensing fee, as profits would be higher for them, but if they couldn’t sell nearly as many games on the 3DO as they could by putting the same game on the upcoming Sega Saturn or Sony Playstation, or even by just creating a game for MS-DOS or Windows instead, then why choose the 3DO?

Eventually, publishers would ask and answer that question, then move on to the alternative CD-based systems with larger install bases and more profits to be had. Things hadn’t quite hit that point by late-1994, though, so EA, a central and key partner of the 3DO company, was still producing exclusives just for their founder’s new venture. (The) Need for Speed was one of them.

The 3DO edition of the game is significantly different from the eventual Playstation port, which would release in the spring of ‘96. There are just three courses in this inaugural release, though, each is broken up into three parts through checkpoints, so there’s far more track than simply saying “there are three of them” implies. The additional three courses in later ports of the game were designed differently, as they were circuit races, instead of having you driving through a city, the coast, or forest mountains. The Need for Speed, in its 3DO form, feels small by modern standards, but try to remember that the initial Ridge Racer, also released in 1994, featured one (1) track, playable at four different difficulties. Virtua Racing, which debuted in 1992, had three tracks. Three courses that’s really nine courses across three environments isn’t all that small, considering.

There were at least quite a few cars to choose from, and mastering them will take time, as your choice will impact how the courses go: driving on the highway, with its wide lanes and space to dodge between vehicles only going one way, is going to be a lot easier for a car that goes a million miles per hour but doesn’t handle particularly well, while something like the narrow, two-way roads of the Alpine course requires speed, yes, but far more control over your vehicle than that highway needs. The 3DO version gives you tons of specs on each car, but if you don’t know what car weight or RPMs or torque mean for a vehicle, or what lateral acceleration is, or what to do with the knowledge that it takes 220 feet for a Ferrari 512TR to come to a stop while going 80 mph, then that’s only so helpful. Later versions of the game would actually split the cars up into groups based on specific aspects like handling or top speed.

The cars are real ones: in addition to the above Ferrari, there’s also a Chevy Corvette ZR-1, a Porsche 911, Lamborghini Diablo VT, Toyota Supra Turbo, Mazda RX-7, Acura NSX, and a Dodge Viper RT/10. Licensing deals like this, as fans of these kinds of games already know, can make re-releases a nightmare. It also impacts localization and international releases, however. In Japan, The Need for Speed was known as Road & Track Presents: OverDrivin’, and two later Japanese editions of the game, one of the Saturn and one for the Playstation, were both presented by Nissan, instead, and featured only Nissan vehicles.

Maybe a little ironically, The Need for Speed feels a little slow at times, but it’s owing mostly to the push for realism that it represented. To bring up Ridge Racer again, the idea was for The Need for Speed to have more realistic speeds and physics, instead of its own rules for both. You’re still going plenty fast; it’s just not the kind of out-of-control speed that pseudo-3D racers that preceded it were putting out. The tracks, though, are much larger, and more varied. Top Gear might have you feeling like you’re atop a rocket, but its design is comparatively basic, since it’s not actually 3D and only so much could be done within a pseudo-3D space in terms of turns and course designs to force varied turns and turn angles.

The Need for Speed is not too slow to get the attention of cops, however. A central game mechanic in this title is that there are cops parked on the side of the road, or driving along at normal speeds, and they will give chase when you fly by them doing 140 mph. You have a warning system in your car to let you know when you’re approaching a cop car, which escalates the noise and red lights as you get closer. And you’ll hear the cop turn its sirens on, of course, as it begins to give chase. You’re going to want to keep going as fast as you can when this happens, lest you be caught and ticketed: you can only be ticketed twice before the third one leads to you being arrested and failing at the course. Though, if you’ve been ticketed twice already, chances are good the delay is going to mess up your victory even though you’ll be allowed to complete the run.

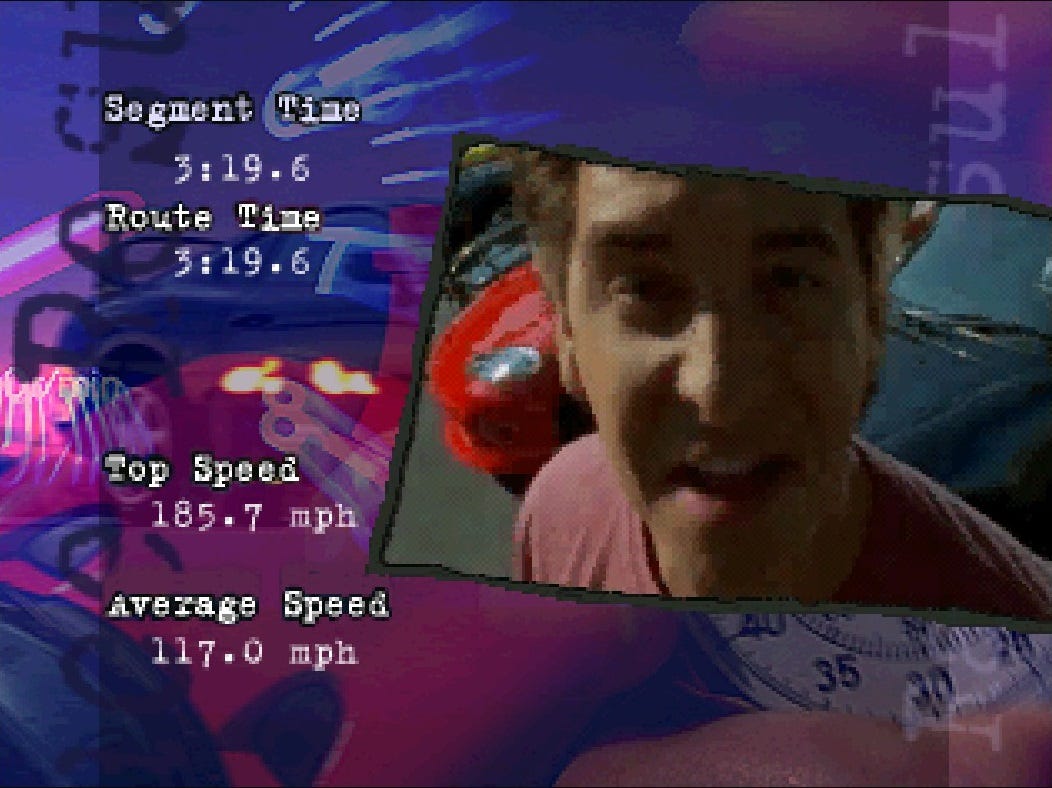

You’ll outrun cops, but most important is outrunning your rival. In the 3DO version of the game, this isn’t some faceless opponent. He has a face, and a mouth, and he uses it to criticize and to praise, to pump you up or advise you to change. This video (beginning around the 6:40 mark) shows all of the FMV sequences featuring your rival trash talking or encouraging you. There are a ton of them, with EA clearly utilizing the CD-ROM format of the 3DO to get a bunch of video and voice work into their racing game.

It’s a genuine shame that these sequences weren’t included in later releases of The Need for Speed, because they give this game a real sense of character. It absolutely dates the game as a product of the 90s, sure, but they were initially put there for a good reason, and they effectively did their job. In a game with no real multiplayer, where the only thing you’re racing besides yourself the whole time is this computer-controlled rival, giving him a personality and the ability to shame you was brilliant — a somewhat lonely experience made less lonely by his presence. The Playstation version of The Need for Speed might have more tracks, but it lacks this dude and that vibe.

Your rival is a problem for you, which makes sense, but he still has to deal with the same game world that you do. Your rival can crash, temporarily slowing him down. He can get caught up behind accidents or other cars on the road, or be pushed off course by you or a truck that simply won’t get out of the way, or a turn that he doesn’t quite nail. There will be times when you’re behind, and suddenly you notice that bright-red Ferrari facing a direction it shouldn’t be, and you blow right by it, retaking the lead. It feels great, and while your rival is skilled enough to catch up without what’s happening feeling like it’s rubberbanding at work, that sort of thing just pushes you to continually improve your own skills and times, so that once you’re ahead, you stay there.

An issue for both of you, as the above implies, is the other drivers. They are not racing. They’re just trying to get to work or the mall or whatever, and they are in your way. Basically perpetually. You have a bit more time to react than you did in the aforementioned Top Gear, but the other cars are a little less predictable than in some other racers, too, as they all get that OutRun-esque desire to swerve and force you to make the wrong call. What can you say? Don’t rush up behind them in a car with a top speed of 192 mph, and maybe they won’t panic while behind the wheel.

The Need for Speed might not feel top of the line now, but in 1994, when true 3D racers were really just getting going, when the market for CD-ROM games was opening up beyond add-ons for existing 16-bit consoles, it was special, and an example of what the 3DO was capable of. That being said, it also stands as the correct answer for what people think they’re saying when they joke that Tesla’s Cybertruck looks like a car from the Saturn or Playstation brought to life before it fully rendered. No, it looks like every vehicle you see on the road in the 3DO edition of The Need for Speed, before it’s close enough for you to tell what it actually is you’re looking at:

No offense intended to The Need for Speed or the 3DO's capabilities here, all offense where it belongs.

It’s a shame that this is a relatively unknown version of The Need for Speed, and not just because it’s the actual beginning of the franchise that’s still releasing entries in the present, three decades later. It explains a moment in history, EA’s role in it, and where they had to go after the gamble on the 3DO fell through for them as well as the other publishers — and manufacturers — who invested heavily in this new competitor in the console space. The 3DO is a system with emulators, however, so if you want to discover for yourself what this game had on offer — and maybe hear some trash talk from an FMV rival — then that road is open to you. And you might not even be chased down by cops, either.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

Wow, $700 for a console in the early Nineties, and people whine about the PS5 Pro today? Very interesting. I also didn't know that NFS started as a 3DO game!