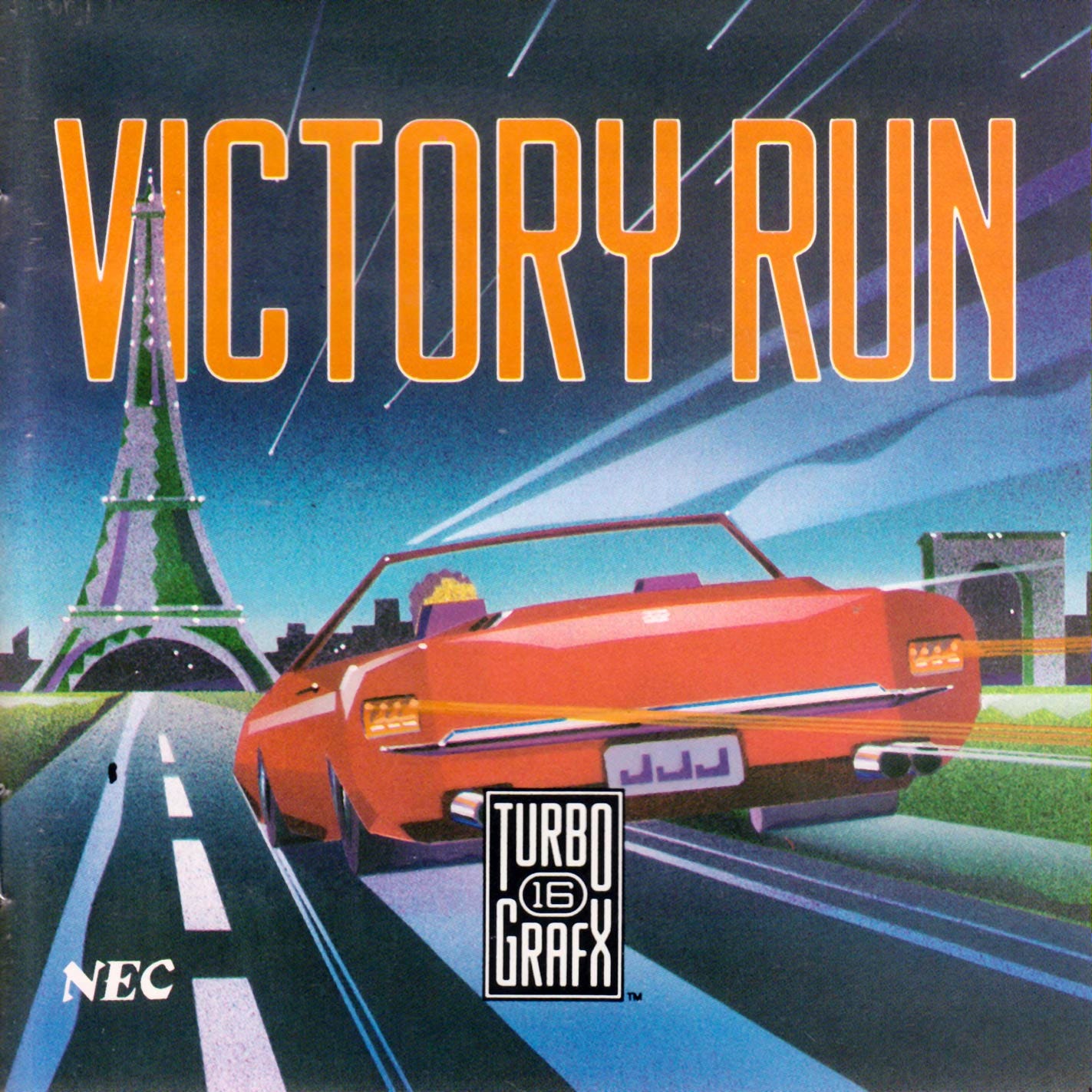

It's new to me: Victory Run

A first-party racing game for the Turbografx-16 that tried to differentiate itself

This column is “It’s new to me,” in which I’ll play a game I’ve never played before — of which there are still many despite my habits — and then write up my thoughts on the title, hopefully while doing existing fans justice. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

The Turbografx-16 could go toe-to-toe with (or at least put up an admirable effort against) the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo in quite a few genres, but racing games? That was a different story. Nintendo wanted to emphasize both their Mode 7 capabilities as well as their Super FX chip and knew racing games were one way to do so, and Sega constantly brought their successful arcade racers to their home console even when it seemed like it would be impossible: both companies poured considerable first-party resources into making their 16-bit consoles appealing to racing game fans, and third-party devs followed suit as they saw both the possibility of the hardware and the success of the genre on them.

That never happened with Hudson’s and NEC’s Turbografx-16 and PC Engine, though, at least not to the same degree. There are racers on those platforms, yes, but the volume is different than what was on the other 16-bit consoles, and there was no killer app like Super Mario Kart or a technological marvel like Virtua Racing or Stunt Race FX on NEC’s console. What the Turbografx did have going for it, though, was that it had racers that were a little different from what you’d find elsewhere. Namco’s Final Lap Twin was a console-specific edition of the popular arcade game that doubled as a racing RPG, for instance. Sega put Power Drift, their arcade kart racer that arrived four years earlier than Super Mario Kart, on the PC Engine but not their own Master System or Genesis. And there was Hudson Soft’s own Victory Run, which released all the way back in 1987 in Japan and then 1989 in North America.

Victory Run looked a lot like racers you’d find on the SMS or NES, games like OutRun or Square’s Rad Racer, but it was pretty different from those titles in a couple of respects. For one, the Turbografx-16 was a 16-bit system, not an 8-bit one, and while it was less of a “true” 16-bit system than the Genesis or SNES because of its 8-bit CPU, it was still very obviously more powerful than its competition of the day, as the first leap into the next generation of consoles. So, there are more colors and more refined graphics than what you’d find in the aforementioned 8-bit racing games, and the roads are also packed full of other vehicles you’re going to have to watch out for. Races change from morning to sunset to night to reflect the length of the drive, and it’s impressive how the entire look of everything changes with this travel through time, like with lights coming on in Paris’ buildings, or the tint of the clouds and sky changing to match the difference in the sun’s coloring of the sky as it sets. Victory Run doesn’t stand up against later 16-bit games from a pure graphical perspective, no, but it’s pretty easy to see how it was a step up from the games it was competing with in the moment.

More important than how it looks, though, is the point of Victory Run: that’s what truly separates its gameplay from OutRun and Rad Racer and games of that nature. Victory Run is based on the Paris-Dakar Rally. Now known as just the Dakar Rally, from 1978 through 2007, most of the events went from Paris, France, to Dakar, Senegal. The races were long, tough affairs that put a beating on the vehicles taking part in them. How could they not, considering the length of the drive and the fact this wasn’t some kind of pleasure cruise? It’s a race that was a marathon for cars, and it would wear on both vehicle and driver.

Here’s a look at what we’re talking about scale-wise. It’s a map of the 1987 Paris-Dakar Rally route, an 8,000-mile rally from the year that Victory Run released:

OutRun was basically just about one guy and his girlfriend driving really, really fast down whichever route they felt like, hair blowing in the wind and all that. Not really a race against anyone but yourself and a clock, and the point was often just to replicate the vibes of driving a Ferrari like it could be driven. Rad Racer was also a race against yourself, though, instead of alternate routes, you were trying to hit checkpoints to keep going on a number of different courses. Victory Run manages to be kind of a little of both of these approaches at once, while also being its own thing, as your early mistakes will haunt you throughout an entire game loop, not just the one race in which they occur in. Mistakes you make in Paris are going to cost you in your approach to Dakar, multiple countries and an entire continent away… if you even last long enough to have those regrets.

Those mistakes will haunt in two ways. Each race segment from Paris to Dakar is expected to take a certain amount of time, and no more: anything beyond that is pulled from a limited pool of seconds, and once those are gone, you lose. So, if it takes you more than the allotted two minutes to complete the very first leg of the rally, you’ll start to see your precious one minute of “extra” time tick down. Even if you finish, you’ll be penalized for failing to complete the stage within the allotted time, but at least you’ll be allowed to continue on and try to do better the next time. And you’ll have to do better, too, because again, there’s only so much time in that pool of “extra” seconds, and it’s Game Over once you run out. If you use up all your extra in the earlier courses, there won’t be much of any for later, which means if you crash in a late-game stage after getting all the way there and don’t have time to carry yourself over the finish line, well. Time to restart the rally.

The other way mistakes can haunt over time is through vehicle degradation. Before you begin your rally, you are tasked with choosing your replacement parts for the race. You get 20 of them, and there are five types of parts, so if you don’t know what you’re about you can just divvy them up evenly and hope that works for you. The different parts of your car don't degrade randomly, however, but instead take damage based on how you are actually driving: if you hit a ton of bumps at high speeds, your suspension will degrade faster, or, if you fail to switch gears when you should, your transmission will suffer for it. So, you have to plan part selection according to how you drive rather than how you expect the game to treat you, while also making sure you've got a couple of spares of everything you don't ride hard, just in case. You can’t race if you don’t have any spare tires, you know? And if your transmission is busted, you’ll be able to drive, but certainly not race.

In between races, you commit these spare parts you’ve selected to wherever they’re needed. Each part — tires, gear (that’s your transmission, but 1987’s menus and text being what they are), engine, suspension, and brakes — has a damage counter, and will change color based on how they’re doing. Blue is brand new: everything besides blue is an indicator that things are wearing down, and you can track this during the races itself on the bar at the top of your screen. If something is only a little broken and you’re limited in replacements, you can run the risk of making it through the next race without swapping it between legs, but the downsides to that plan should be pretty obvious. You can race without perfectly working brakes just fine in the sense you can account for it by letting go of the gas earlier, but everything else is going to be a real issue that’ll cause you to lose.

The elements specific to the idea of doing this extended rally — picking replacement parts you bring "on the road" with you, the fact this is one long race with stoppages at various destinations — is a real cool idea. And in practice, it works. It might even work a little too well. Victory Run is a tough game, and some of that isn’t because of the nature of the rally. Turns sometimes come out of nowhere because of how the car often sits on the road and how the camera positions itself because of that: you don't necessarily have a great view of what's coming or which way a car in front of you might be about to move or change lanes, and unlike some other titles in this specific style of racer, there aren't any signs indicating that hey, you're going to want to start turning left soon. Which can be a real pain considering that you can time out, and timing out becomes even easier to do, the further into this you get and have pulled from your store of emergency time. If you crash in OutRun, at least you can blame yourself for not reacting to telegraphed changes in the road quickly enough, or because you didn’t properly account for those changes. Just a little too often a crash occurs in Victory Run because something you couldn’t account for occurred. Realistic, yes, but maybe not always in an enjoyable way.

That being said, the difficulty is certainly the point here. The game remains a challenge regardless of how long you've been playing it and mastering it: the Paris-Dakar Rally itself is a grind, and the game reflects that. Your enjoyment of Victory Run, which plays and feels like you would expect a racer that looks like this one to play, is almost entirely up to how you respond to its difficulty. Victory Run was never a showcase racing game or the start of a run on TG-16 purchases, because it's a racing game for sickos. And while that's appreciated, there are only so many of the particular type of sicko it was trying to attract out there. This isn't a criticism, either, more games for sickos, please, even if the majority of people will either never hear of them or turn their collective noses up at them. Just, you know. Non-sickos need not apply here.

Victory Run, unlike the rally it’s based on, isn’t a terrible lengthy game, but none of the racers of the era were, either, and pure length of making it from start to finish isn’t the point here, either. The game is so tough, and will take so much practice to even have a chance at completing it — and your chances of not completing it remain high even if you’ve put hours and hours in or have completed it before — that "length" just doesn't fit in here. Victory Run remains playable and difficult even if you're any good at it, and might be rude and destroy you even if you're great, since all it takes is one mishap to start that ball rolling downhill. If you’re not interested in that level of punishment, then Victory Run will do nothing to pull you away from the competitors of its era or whatever racing games you’re into instead. If you’re curious about a potentially brutal experience that doesn’t pull punches and seems to expect more from you than you’re maybe capable of, though, well. Here’s a racing game for you.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.