Past meets present: Battle Garegga Rev.2016

An arcade classic whose true brilliance was hidden under its many secrets, now unveiled in the present.

This column is “Past meets present,” the aim of which is to look back at game franchises and games that are in the news and topical again thanks to a sequel, a remaster, a re-release, and so on. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

The concept of rank is a well-known one for shoot ‘em up fans that dates back nearly to the beginnings of the genre. It’s not “rank” like where you rank on a score leaderboard, but instead is a calculation and grade inside of a shooting game that essentially determines how difficult your playthrough is going to be. While the earliest shooting games that became sensations like Taito’s 1978 mega-hit, Space Invaders, lacked rank or any kind of adaptive AI to counter how well a player was doing and ensured they wouldn’t be able to play indefinitely or without challenge, it didn’t take very long for such features to emerge.

Namco, as they did with basically everything in the 80s arcade scene, had a hand in developing rank and adaptive AI. Galaxian is the precursor to Galaga and seems relatively simple in many ways, but according to designer Kazunori Sawano (in an interview localized by shmuplations) its enemies adapted to your movements over time so that you would have to adapt to them in turn — the divebombing the enemy ships perform toward your own ship isn’t random or pre-programmed for a specific pattern, but is instead a direct reaction to your own movements. Namco’s 1981 multidirectional shooter, Bosconian, reacts to your behavior and scales the difficulty up or down based on whether you’re taking too long to complete a mission because you’re score-chasing, and if you aren’t stealthy enough to take out the space stations before they see you and deploy formations of fighters. Xevious, among its many innovations, utilized a rank system more akin to what the genre would be used to seeing from that point forward. The more you score and the longer you survive, the more aggressive enemies become. Their speed increases, and enemy types you’ve had considerable success against might even vanish from the game, to be replaced by more difficult spawns. You can reduce rank a little bit by blowing up the red towers on the ground, and a lot more by dying, though that’s not recommended. In the Namco Museum DS edition of Xevious, you can even choose to display the rank on the touch screen, giving you a sense of what actions feed into its calculation.

Namco was far from the only developer programming their AI in this way or including a true rank system like in Xevious. Sega’s Fantasy Zone would punish you if you took too long to complete a stage or you looped around the map too often, by introducing more difficult enemy formations that would shoot more complex bullet patterns more often, and your reward for surviving them was less money than you would have received by just moving on to the next stage. Compile, famously, brought adaptive AI into overdrive with the systems used in games like Zanac and Aleste: enemies and enemy patterns were procedurally generated, and were a direct response to your armaments, weapon levels, and success with them. It made the games quite difficult when you died deep into a run, as you would suddenly be firing your pea shooter once again against onslaughts of enemies and bullets that hadn’t quite caught on to the fact you were now a lot weaker and less fully armed than just a moment before. The games are much easier if you don’t fully power-up, which seems counter-intuitive, but it mostly makes it so less skilled players have a chance at completing the game while more skilled players can find the challenge they’re looking for.

Zanac wasn’t the only game to build in systems where powering up punished you: every power-up in Konami’s Gradius also buffs up your foes, and its parody series, Parodius, does something similar, while also scaling up difficulty the longer you’re able to survive. It’s not enough to avoid being powered up: simply existing within it will make Parodius more difficult.

Taito might not have had a rank or adaptive AI system in the earliest days of their shoot ‘em ups, but by the 90s, they were not just on board with the concept, but coming up with complicated rank systems of their own. Masterpieces like Darius Gaiden and G-Darius used not just how long you avoided dying or power-ups to calculate rank, but took a page out of Bosconian’s book and made the game more difficult if you spent time destroying pieces of bosses to enhance your score instead of just going for the kill. If you destroy entire enemy formations, rank goes up. These two items are both score-chasing, expert behaviors, and the game responds accordingly. It also punishes you for a lack of finesse, though: shooting your gun all the time and missing shots with it increases rank. Increased rank in these Darius games means not just faster enemy bullets, but more of them, and larger ones, too.

RayForce (or Layer Section, or Galactic Attack, depending on where in the world and on what platform you’re playing it on) used cumulative rank based on your completion of levels in conjunction with whether you managed to avoid dying in a given mission. The rank goes from 0 to 7 and begins on 1 — dying drops it, surviving increases it. So you can reach max rank before you’re even halfway through the game if you avoid dying, which allows rank to plateau, sure, but you’re also playing the most difficult version of RayForce possible if you manage that. Dying isn’t so bad in that game, but you still shouldn’t exactly do it on purpose. That’d be lunacy, yeah, to intentionally kill yourself to keep the game manageable?

And then there’s Taito’s Gun Frontier, which is obvious inspiration for today’s subject, Battle Garegga. If you’ve played both games, you’d be aware of that just from some of the systems and design choices the two share, like how you collect bombs and the realistic-looking bullets that are more difficult to pick up on than the brightly colored rounds of so many other shooters, but you don’t even have to guess at it: one of Garegga’s programmers, Shinobu Yagawa, has publicly expressed his love for Gun Frontier. Yagawa’s games tend to be complex and deep: early work of his includes a game that seemed impossible on the Famicom, Recca, and he would eventually move on from Raizing — the developer of Battle Garegga — to Cave. Shoot ‘em ups don’t tend to get more complex and deep than Cave’s frantic offerings, and Yagawa’s own projects there were no exception.

The shorter version of the above: many shooting games don’t just get harder because you’re further into them. They also become more complex and difficult as a direct response to how much success you’re having within them! Sometimes with in-level calculations, sometimes after levels, but the result is the same: the game becomes more or less difficult depending on how well you’re doing or not doing, and in what ways.

What Raizing’s Battle Garegga — first released in 1996 after every game mentioned above had already been on the market for some time — does is both something else entirely and obviously built off of these systems in an on-the-shoulders-of-giants way. Garegga is never introducing more enemies due to your rank, but it will include more bullets, and faster ones, too, while also making enemies much tougher to kill. “Enemies” there also includes bosses, so if your rank is high enough to make the levels challenging on their own, giving bosses significantly more hit points, armor, and much more complex and difficult to navigate bullet patterns might very well mean your end. A high rank in Garegga means that the screen will fill with so many bullets fired by foes with such high armor and health that it will become literally impossible for you to proceed beyond a certain point in the game. It’s basically a blend of everything that came before, put together into a massive system that requires time and practice to sort out in order to understand how it even works, and how to control it for your own benefit.

Garegga’s obsession with rank, and the need for you to fully understand that it exists and how you have to control it, has made it wildly divisive over the years. To those who know of it, it’s either one of the most brilliant, depth-filled, and rewarding STGs of all-time, or it’s overrated and just not very much fun due to the sheer number of walls it throws up in your way. Considering the length of the preamble here, you can probably guess which camp I’m in.

In Garegga, everything increases your rank. Literally everything. Before you even fire a shot, your rank begins to increase: no joke, while taking the screenshot of the ship selection screen embedded above, the game’s start rank increased by 0.1 percent. Firing your gun increases your rank; holding down for auto-fire increases it even more, and holding it down to fire when there aren’t even any enemies to be firing at is something you will learn to regret. Scoring points increases your rank, picking up power-ups increases it, picking up the point medals increases rank, too, but not picking them up can increase it even further. Picking up bomb fragments increases rank, and holding on to bombs for too long also increases it. Playing well enough to have extra lives increases your rank, and if you go beyond having two in reserve, rank will increase even more aggressively to correct for this grave mistake you’ve made.

If you pick up every power-up, every point chip, hold down auto-fire, hoard your bombs, and have all the lives that come from scoring all these points, you’ll come to a mid-game wall in Garegga that you won’t be able to breach. Not a literal wall, no, but an outer wall of bullets moving too thickly and quickly for you to avoid, fired by an inner wall of ships whose armor is now too thick for you to penetrate in a timely fashion. And here’s the kicker: the game doesn’t tell you any of this. You could guess about some of the things that increase rank, but if you were playing it the way you thought it needed to be played, like it was any other shooter, you might just think that the game always ends up this hard as you get deeper into it. That’s not the case, though, and over time and with a whole bunch of trial and error, exactly how Garegga’s rank system works was unearthed and compiled together into an absurdly detailed guide on a shoot ‘em up message board, System 11. Prior to 2016, we knew everything about how Garegga worked solely because of the work of those individuals who put their experiences together into a guide.

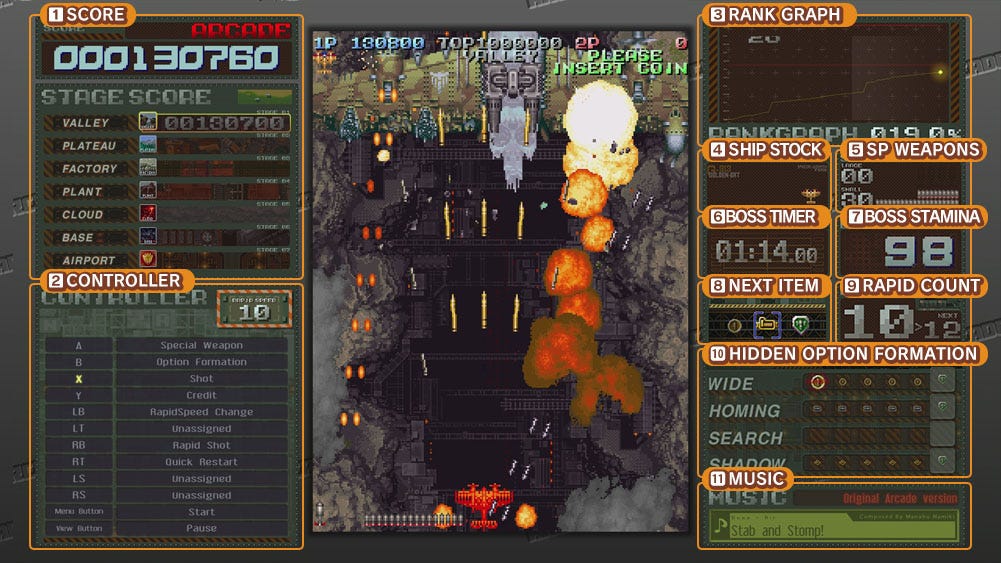

In 2016, to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Raizing’s classic, M2 released Battle Garegga Rev. 2016 as part of its ShotTriggers line. No longer did you have to guess or read a guide in order to understand how Garegga worked or how it expected you to play. You could now view, in real-time, how your actions impacted rank, thanks to a line graph on the top-right of the screen. Whenever it flashed red, your rank increased, and it wouldn’t take you long to notice that it flashed red constantly following every action and even some inactions.

Watching the graph out of the corner of your eye, just like reading the guide in full beforehand, can teach you about how you should be playing Garegga. You still form your own specific, individual path for your run, which is part of the beauty of Garegga’s complexity and freedom, but knowing how the rank system works can explain to you what your choices even are in the first place. Maybe you don’t want to upgrade your guns early on, because it’ll mean rank will increase faster. Plus, trying to survive with your basic weapon at its basic level without a full complement of options to flank you can make you better at the game in general, giving you a stronger foundation for repeat plays. (Options, in STG parlance, are the small ships, fairies, drones, whatever depending on what game you’re playing that flank your ship and either provide some kind of shielding, defensive power, or shoot along with you to add to your overall firepower.) The longer you can go without fully upgrading your weapons, the better. Knowing this, maybe you skip out on upgrading your primary weapon, and instead focus just on adding the options so you have a wider spread. Of course, more shots being fired means rank increases faster, in addition to having your rank increase because you’re powered up. What a pickle.

It goes beyond those comparatively simple deductions, though. Smaller power-ups cause rank to increase in aggregate more than their equal in a larger, single power-up would, so it makes sense to skip the little guys and grab the bigger ones when they fall. Since power-ups increase your rank, you definitely don’t want to collect them when you’re already powered up; yes, you receive points for those pickups, too, but the point totals aren’t worth the increased difficulty. You’ve got to constantly be thinking long-term while playing Garegga. Score chips — those golden medals — increase your rank, but you need them if you’re going to earn extends, and given the nature of the score chips, you’re not going to want to be selective about collecting those like you are about power-ups. The smaller the chip is, the fewer points it’s worth and the more it increases your rank. If you miss a point chip, your streak snaps, and you go back to the smallest ones, which begin at 100 points. (Missing one chip when multiples of the same value are on screen together is fine, but anymore than that and you’re in trouble.) The maximum chips are worth 10,000, which can add up in a hurry when you’re deeper into the game and the volume of enemies has increased. You’ll want to get every one of those, even in risky situations, because not getting it is only going to create even riskier future situations to contend with.

One of the more active mitigation techniques you must employ is using your bombs. And often. Shooting games, from the introduction of bombs to the present day, often focus on not using your bombs and rewarding you for it. Toaplan’s Tiger-Heli introduced the idea of the screen-clearing bomb to STGs, but it’d also give you a serious point bonus at the end of a stage for still having bombs in your possession, with more points coming your way the more bombs are left. They’re often meant as a last resort, a way to avoid burning an even costlier extra ship. In Garegga, though, bombs are how you find hidden caches of point chips, how you do things like unveil hidden environmental bits like the flock of flamingos on the second stage, which, if you then attack with your ship, will allow you to score a not inconsiderable number of points in short order. And they also help keep your rank in check, since not having bombs at your disposal keeps rank from increasing in that specific way.

Bombs are more powerful if you collect enough bomb fragments to make a whole bomb, but you’re better off using them before you get to that point when they’re still in fragment form, so that you can find these hidden point caches, or to avoid death by a basic enemy bullet you won’t be able to get out of the way of, or to just briefly, in the words of President Thomas J. Whitmore, plow the road. If you can reveal a hidden point chip cache with six or eight or however many 10,000 point chips because your streak is maxed out at the point you blow the lid off their hiding space, that’s a huge boost to your quest to earn an extend. Since Battle Garegga has exactly one (1) hidden, collectable extend item in its entire seven stages, you’re going to need those points.

And you need extends in Garegga more than in most other shooters for one very specific reason. You’re going to intentionally die. I asked earlier if it was lunacy to intentionally kill yourself in a shoot ‘em up to keep the game’s rank manageable, and it is. Lunacy is what you need to survive Garegga, though. You won’t live unless you die: Battle Garegga marries survival and scoring in a way that shooters don’t tend to do.

Oftentimes in an STG, scoring and surviving are separate ideas to explore. If you’re score-chasing by destroying everything in sight in Darius Gaiden or what have you, the game will counter this by making the game significantly more difficult. Your goal might not be to finish the game on one credit in this scenario, but to score as many points as you can before your inevitable doom. So, your decisions aren’t made with the long-term in mind, but with scoring as many points as quickly as possible until you can’t. If you wanted to complete Darius Gaiden on one credit, though, or at least on as few credits as possible, you might take a different approach, and avoid doing the things that put you in more danger but allow you to reap significant scoring rewards. It’s not prudent to destroy all the parts of a boss and then make the next stage more difficult if all you’ll get in return is more points, not when you can focus on its primary weak point and kill it outright, limiting your exposure to danger in both the present and the future.

Garegga doesn’t work like that. To survive, you must chase score, but to raise your score, you must survive. And to survive, you must control your rank, which means you must die. You will learn, over time, where it makes the most sense to intentionally get yourself killed in order to lower rank. Maybe it’s before certain bosses you struggle against. Maybe it’s during a boss fight, so you can melt some of their health with the shrapnel from your exploding ship. Maybe it’s right before a massive hidden point cache that’ll require a couple of bombs for you to use, so you use the first one, get killed, then respawn with another bomb ready to deploy. What you need to accept in Garegga is that dying is a part of life, and it’s the only way you’re going to keep the game’s rank from spiraling out of control.

Your alternative is to eventually hit a point you can’t proceed through, as the longer you wait to die on purpose and lower your rank, the loftier it will have climbed, which means the distance between “oh god this is too difficult” and “hey I can do this” has widened, and might never be narrowed again. Stage five is essentially a boss rush that follows an actual standard level, where you face more difficult versions of a couple of the bosses you had already faced — more difficult because rank is higher by stage five than it was in stages one and two when you first faced them — and then you face off against an entirely new opponent that fills an entire horizontally- and vertically-scrolling screen and is loaded with various weapons aimed at you, and then you take on the toughest boss in the game to that point, which goes through long stretches where it’s firing too many bullets too fast for you to be able to harm it. Do you really want to face that thing when it’s firing even faster, more complex bullet patterns, and also it has more armor to contend with? Did I mention there are two more stages beyond this one, and that the final one includes an even more difficult version of the to-that-point toughest fight in the game? And that it’s just the first of three boss fights in that final stage?

Like I said, you’ll need to strategically die in order to live long enough to even see these parts of Garegga on a single credit, never mind actually make it through them.

There is considerable customization in Garegga, not just in your in-game approach, but in how you start. There are four different ships to choose from — well, eight, but those are unlocks and are from another Raizing game known as Mahou Daisakusen or Sorcer Striker depending on where you play it — each with their own differences in speed, guns, and bombs. The gun differences include things like bullet size as well as how easily they’ll shred enemy armor. You can use the ship select screen to choose what the focus of your ship will be: in arcades, you’d press the A button to select the standard version of each ship, B for one with increased movement speed, C for a smaller hitbox, or press all three simultaneously for a faster ship that also has a smaller hitbox. (In home ports, you press whatever the corresponding buttons would be, like on the Xbox Series X, X is A, A is B, and B is C.)

You might wonder why you’d be able to choose to make yourself harder to hit like that, or why anyone wouldn’t choose to be that way, especially when it’s advertised as a feature and not a secret in a game already loaded with those. The smaller hitbox might actually be a curse, depending on your skill level, as it can make collecting those point chips more difficult, which increases the chance your streak will snap, which in turn will increase your rank. Meaning you might actually make the game more difficult in a number of ways by making yourself harder to hit. Garegga has its own logic, and you can learn it. You also have to learn it.

Graphically, Garegga seems a little simple in a screenshot, with muted colors for enemy ships and those realistic looking basic rounds, as well as clouds of smoke and shrapnel following an explosion. In motion, though, it’s gorgeous, with incredible explosion effects and vibrant weaponry colors that really pop off of those seemingly drab-colored backgrounds and foes. It’s a wonderful blend of futuristic sci-fi conventions with more “modern” weaponry and design, and you’ll find that, like with the game’s rules, there’s a significant amount of detail to be discovered in the visuals.

The soundtrack is excellent, as is the arrangement made special for M2’s Rev.2016 re-release. Stab and Stomp is a perfectly aggressive boss theme that’ll add the right amount of tension to what is already an exceptionally tense situation:

Even the more relaxed themes have a beauty and purpose to them that’ll be readily apparent even while calculating rank-influencing decisions in your head on the fly.

There’s maybe never been a shoot ‘em up that needed M2’s ShotTriggers gadgets more than Battle Garegga. They show you not just your point totals and how many points you scored in a given stage, but there’s the aforementioned line graph that charts rank’s gradual increase and sudden, death-inspired dips, a full explanation of what state your weaponry is in, how many hit points bosses have left as well as how much time you have remaining to defeat them, how fast rapid-fire shots are firing, which item will drop next from foes that drop them, and what order you need to pick the various collectibles up in in order to unlock the hidden option formations for your ship. Such as the one that sends all the options off of your ship and directly at a target to absolutely obliterate it from up close.

Hey, you’ll never believe this, but achieving and using a hidden option combination actually increases your rank, so for those playing the game on the arcade difficulty and managing their rank, it’s actually a screen that shows you how to avoid unlocking any of those hidden option combinations. In that case, you’re better off just cycling through the standard formations, which you can do with the C button — those allow you to go for a wider or tighter spread, or have the options rotate around you and fire in all directions, or fire behind you, or have them mirror your own movements to fire in the direction you’re moving in, whether it’s forward, backward, or to the side.

The M2 ShotTriggers release is the definitive version of the game, not just because it includes the original Japanese arcade release of Garegga (and not the international one, which for whatever reason disabled scoring-based extends as that System 11 guide will tell you), but it also includes all of the little additions that the Sega Saturn port made to it back in 1998, which included an arranged soundtrack, options that auto-enabled the use of those four hidden Sorcer Striker ships, the ability to emulate the arcade original’s slowdown, and more. This is the edition of the game I was familiar with before getting my hands on an Xbox Series X, which could play the backwards-compatible Xbox One release of Battle Garegga Rev.2016. Besides the gadgets, M2 also included yet another arranged soundtrack, as well as two additional difficulty levels that change the way the game is played. Super Easy does what it says on the box: it might prove tough for STG rookies, given this is still Battle Garegga, but it’s probably an automatic one-credit clear for veterans, and best-used for them as a way to learn about enemy movements and hidden locations and such.

Rank isn’t so much of a factor in the Super Easy edition of the game, and you won’t lose a life when struck so long as you have a full bomb in stock: instead of dying, the bomb will go off, clearing the screen of a whole bunch of enemies and bullets, all while allowing you to live on. The Premium difficulty is an arranged mode of the game made specifically for Rev.2016, which incorporates rank far more than Super Easy, but it still is a more gradual, mostly designed increase that’ll see you end up in about the same place not completely regardless of your behaviors, but with all of the decisions you make being less punishing than they are in the standard arcade mode. This, too, is an excellent training ground for playing the original version of Battle Garegga, especially since the difficulty does grow enough over time to make a 1CC something you have to work at instead of just being virtually automatic.

The game is at its best in its original arcade difficulty, and when I say it’s tough, this is no exaggeration. As of this writing, my best outing of Battle Garegga on the arcade difficulty has me sitting at number 70 with over 2,560,000 points on the online leaderboards of anyone worldwide with an Xbox One or Series S|X who’s played the mode. I’ve yet to complete stage four (of seven) on a single credit, as I ran out of ships late into that boss fight, and those leaderboard scores are based on what you can do on one credit, the first you play on in a loop. Think about that for a second: a little more than halfway through the game earned me that lofty of a place on the leaderboards, whereas completing the entire game on Premium difficulty and scoring over 8 million points in the process can net you “just” a top 50 slot on that particular leaderboard. The arcade version of Battle Garegga doesn’t mess around.

M2’s release has a couple of other options worth mentioning. If you can’t stand the muted color of the game’s standard bullets, which can be easy to lose in the smoke of explosions and shrapnel from blown up ships, you can change the color of them here so they pop a bit more. You can also choose to hard reset the “cabinet,” which tends to have rank not fully reset after a game over. So, if you want to avoid starting a new playthrough with rank already up a bit, you can utilize that option, but if your playthrough wasn’t going to result in a new high score to post, you can also go to the options menu and choose to go right back to either before ship select or immediately after it in order to save some time. A useful feature when you don’t want to nail the timing of pressing X, A, and B at exactly the same time again on ship select.

Battle Garegga isn’t for everyone — not even shoot ‘em up enthusiasts can agree on just how good it is or isn’t, never mind people who aren’t in the middle of those discussions with others or inside their own heads. Battle Garegga Rev.2016 certainly made it a game that can reach a larger audience, both with its platform and changes made for more inclusive difficulty, but even then, this is still a wildly difficult and demanding game in a niche genre. And that’s fine. There should be more games like Battle Garegga that want you to earn it. Not all games are like that, and that’s fine, too! Inclusive games and ones that want you to struggle, or even those that actively don’t want you to succeed unless you learn the equivalent of a new language in order to understand what’s needed from it, can all exist in harmony. Battle Garegga Rev.2016 manages to be all of those things at once, which is the finest result of all, and the most difficult one to pull off. How fitting, considering the game it managed to pull that trick off for.

Thanks to @HG_101 for helping point me toward the confirmed origins of rank and adaptive AI in shoot ‘em ups; historically, coverage of these trends uses “one of the first to” language rather than “was without question the first,” and the why of that seems to be that this was a series of small pieces of basic rank and adaptive AI that were later put together into more complex systems by other shoot ‘em ups.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

Cool, now I'm totally obsessed with a game I'd never even heard of this morning.