Past meets present: Gleylancer

What was once a prohibitively expensive Japanese-exclusive Mega Drive game is now available worldwide on modern platforms, and it's great.

This column is “Past meets present,” the aim of which is to look back at game franchises and games that are in the news and topical again thanks to a sequel, a remaster, a re-release, and so on. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

There was once a time where the only way to play Masaya’s 1992 horizontal shoot-em-up, Gleylancer, was to own a Sega Mega Drive and live in Japan. Or, if you didn’t live in Japan, you still needed a Mega Drive, and a way and the means to import Gleylancer to wherever you were. Or maybe it was a few years after this, even, and rather than importing the game, you emulated it on your computer: unless you could read Japanese, though, you missed out on all of the story elements, which existed in the form of anime-style panels. The same problem existed in 2008, when Gleylancer was released worldwide on the Wii’s Virtual Console service, but at least you could still experience the rest of what the game had to offer, without spending big money on importing a shmup rarity.

That was then, though, because, as of October 15, 2021, Gleylancer is once again available worldwide, nearly three years after the Wii’s Virtual Console was shut down… and now the game has finally been fully localized by someone other than fans, too. Now you can download Gleylancer (for $6.99) on the Nintendo Switch, Playstations 4 and 5, as well as the Xbox One, Series X, or Series S. Sometimes the future is hell, and sometimes it localizes Gleylancer and sells it to you for $200 less then Ebay would.

We can discuss the specifics of this modern release of Gleylancer a little later. Before knowing what’s a bit different this time around, however, you should know what Gleylancer even is. It is not a game that’s exactly bursting with new ideas or level designs — it owes a tremendous debt to the heavy hitters of horizontal shmups, like Gradius and R-Type — but the one truly new wrinkle it brought to the table was more than enough. Gleylancer has “options,” which in shmup speak are the little assist craft that fire weapons or shield your ship in a variety of games, like the aforementioned R-Type and Gradius. What makes these options unique is that they’re known as “movers,” because that’s what they do. Whereas in R-Type you can fire off your option and attach it to the front or back of your ship, in Gleylancer, these assist craft can be fully controlled the entire time you’re playing. On the original Mega Drive, you could control your ship with your directional pad, but at the same time, you’d be pointing the movers. If you wanted your ship and the movers to move in separate ways, you held down the C button as you piloted. That way, you could lock in the movers at a diagonal angle, or behind you, or wherever you wanted while you navigated your ship around projectiles, enemies, obstacles, whatever.

It made for a game that had very familiar level design on the surface, but all of the stages could be played a very different way than you ever had before. And since this kind of setup was not widely adopted throughout shooters, it’s still, nearly 20 years later, mostly a unique experience. I say “mostly,” because Gradius V — developed by Treasure and G.Rev and published by Konami in 2004 for the Playstation 2 — utilized a similar system with its options, but that wasn’t a universal thing like in Gleylancer. That depended on what kind of weapon loadout you selected for your ship prior to beginning your game. In Gleylancer, the entire game is designed around the idea that you will be able to shoot at 16 different angles, so you’ve got enemies not just from the front, but from behind, from below, from above, and often tucked away behind obstacles in a way that keeps you from being able to tackle them head-on with your ship’s primary cannon.

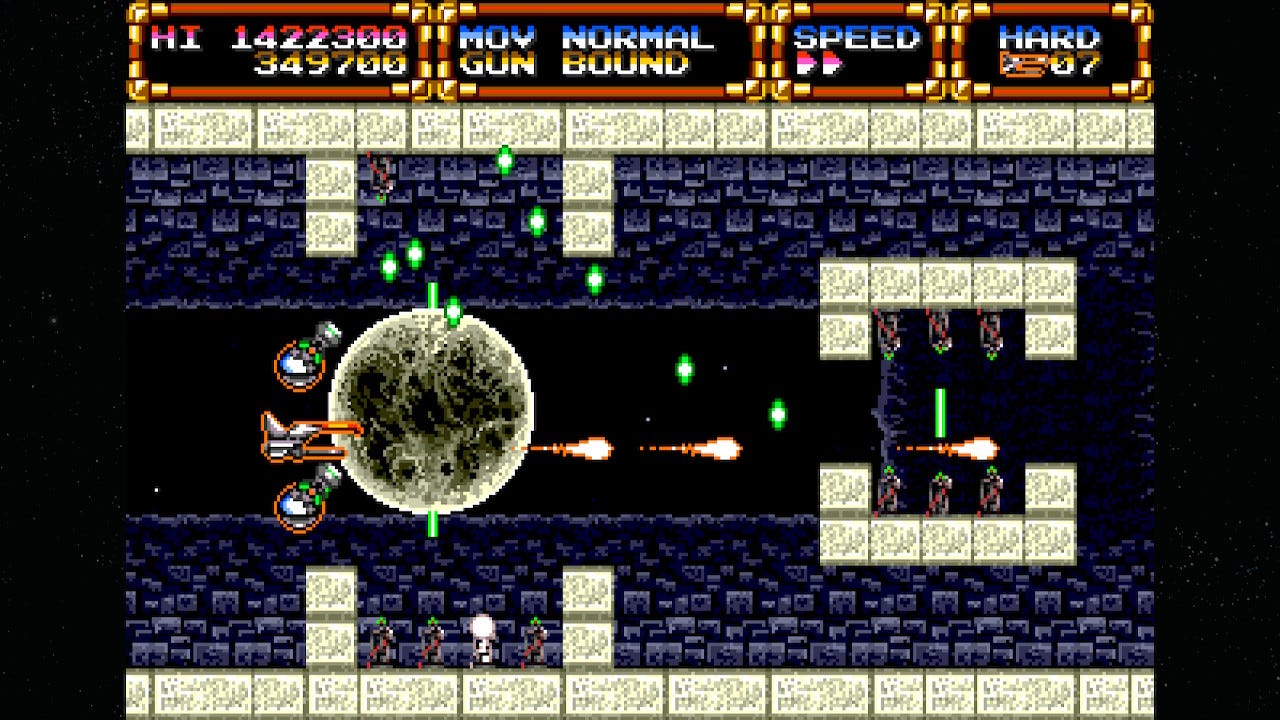

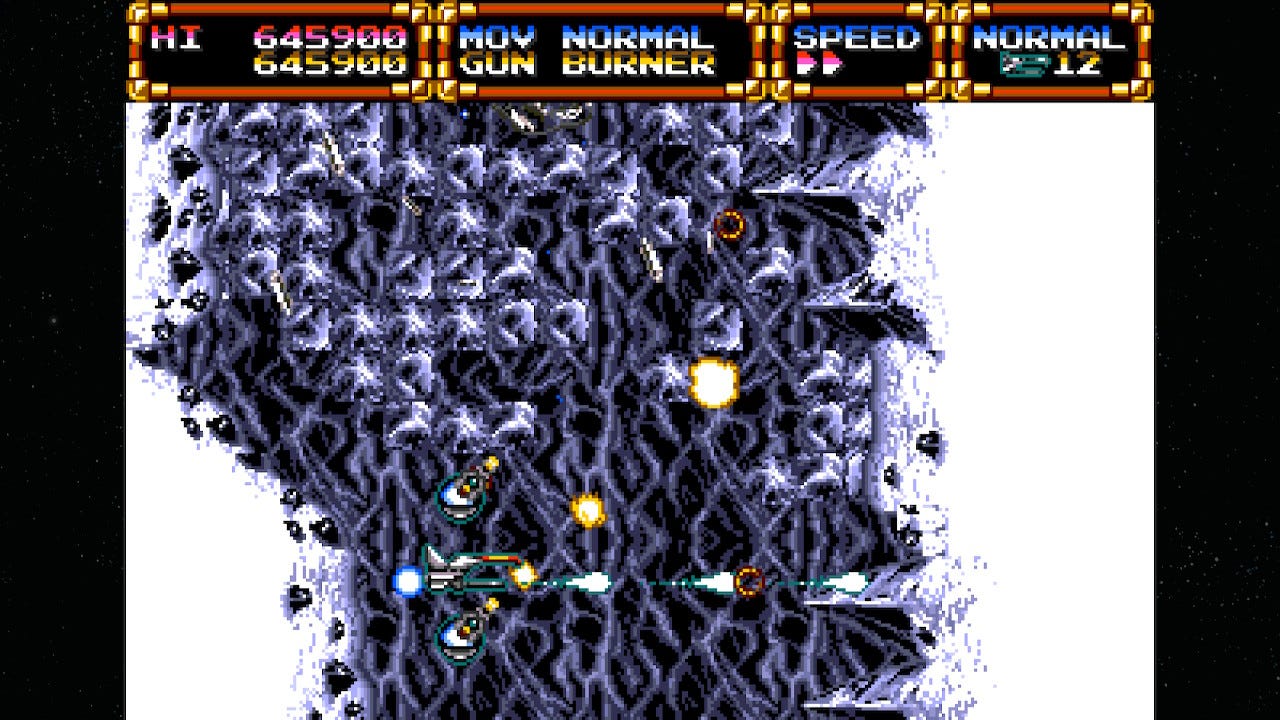

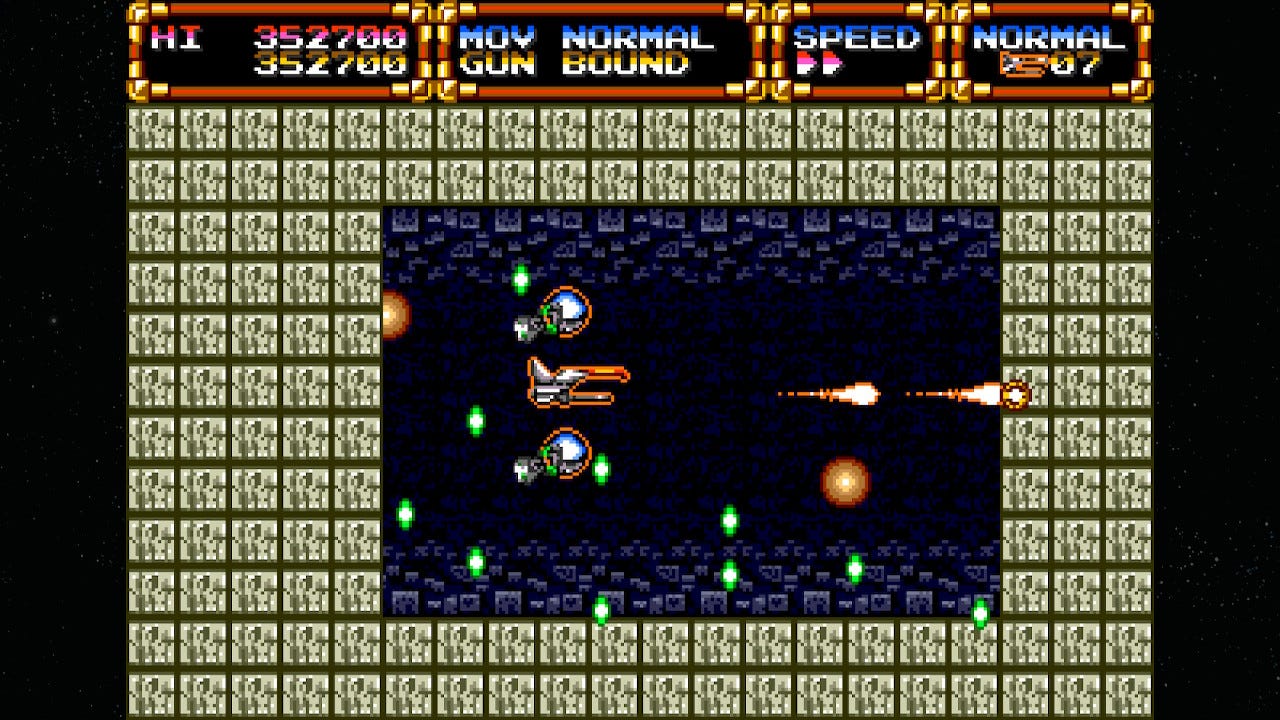

The screenshot above shows an example of a moment where you need to focus on piloting your ship through a barrage of weapons fire, while aiming your movers both up and down at the guns trying to shoot your ship down — guns you can’t reach with your forward cannon. There are also instances like the one below, where your ship isn’t even able to point at what is in your way, so you need to angle the movers to clear a path for you, while also using them to take out any enemies that pop in anywhere besides in front of your ship. And since you’re in a vertical tunnel that is scrolling upward, basically anything you see is coming from where your ship can’t aim at it.

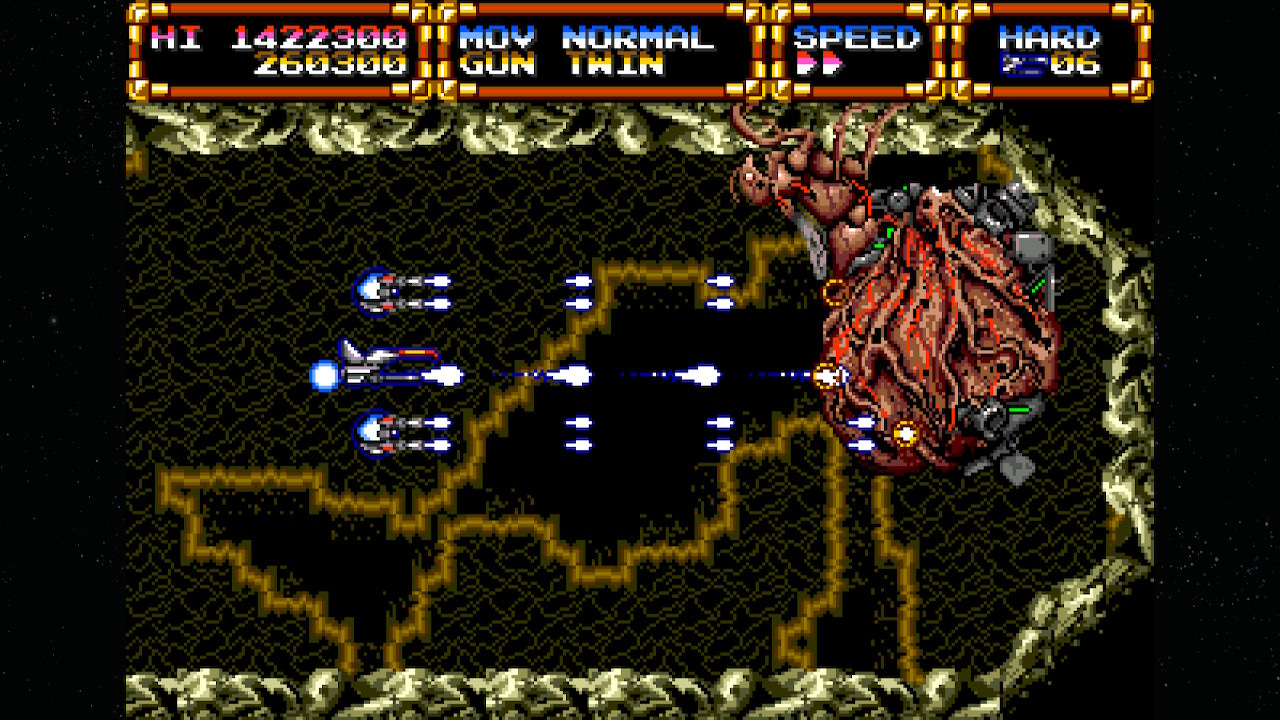

And then you have this boss fight, where the room starts to shrink around you: the boss continually appears and disappears, with only brief moments where you can attack it, and each time it vanishes, the walls close in a little bit more. You need to be able to precisely aim, using your movers, at this, the smallest boss in the entire game, in order to avoid being crushed to scrap. It’s a fight that’s actually most easily won using the saber weaponry, where your movers essentially have enormous lightsabers attached to them that can be “swung” around by your movement of them.

It all makes for a game that feels familiar and yet plays differently than anything it reminds you of. The level design is at its best when it borrows more liberally from the likes of Gradius and R-Type, when it attempts to slow down and bring claustrophobia and fixed scrolling in multiple directions into the mix, in part because it really emphasizes that this is a new way to play the old hits. It also works exceptionally well when it decides to speed up or slow down within a single stage, too, since it brings in-level adjustments from you not just on how to move, but how to fire and anticipate danger, and the kinds of dangers, too. Sometimes a stage is about firing as much as possible in as many directions as you can to stave off destruction, and sometimes you’re being hurtled through a stage as fast as the game can process it, trying to avoid slamming into barricades that’ll spell your doom.

And even the movers themselves have a level of customization to them: there are a variety of ways you can make them work, which basically amount to “what kind of dual movement setup makes sense to your brain?” — that’s what the “MOV NORMAL" text in the trio of screenshots above is referring to, by the way. You can also choose Reverse, which has the movers go in the opposite direction of your ship instead of the same one. There’s a Search mode, where the movers will basically aim at whatever they think is a threat, but the game even warns you that this might be taking your life into your own hands since you’re flying around in a prototype ship. There is Multi and Multi-R, which restricts your firing to horizontal directions but concentrates it, Roll, which has the two movers constantly rotating around the ship, and Shadow, which has the movers trail behind your ship while imitating its every move. Personally, I enjoy the full control afforded by the Normal option, especially since I’m already having to juggle moving the ship and moving the guns at the same time, which can feel like trying to pat your head and rub your stomach at the same time but with the same hand.

You’ve got a variety of weapons to choose from in Gleylancer, and they all work well, though you can certainly develop preferences. There’s some pretty standard twin cannon, a five-way shot that is weaker but has a real spread that covers basically everything in front of you range-wise, shots that bounce off of walls and ceilings and floors at whatever angle you shoot them at, flamethrowers, the aforementioned sabers, and more. You can use just about anything and thrive, but there are certainly cases where one weapon type can work better than another, so keep an eye on the logo for the upgrade in order to avoid accidentally “downgrading” in a given moment.

The game isn’t particularly difficult, though, the difficulty can be uneven. Much of my trouble with it, both originally and in subsequent playthroughs, has come early on, as I’m rewiring my brain to let me control the ship and movers while paying attention to the location of both on-screen: that’s usually when some stray laser fire I didn’t notice (possibly due to the parallax scrolling asteroid field found in the first stage) melts my ship and costs me a life. Once I get my head in the game, as it were, the points and extra lives start to rack up, however. That’s when you feel comfortable controlling the ship and movers separately, when you’ve found your comfortable cruising speed but also know when to adjust to move your ship faster or slower — the last boss fight requires you be able to fly at the higher end of the game’s four speed settings, or else you will not be able to avoid its continuous spiral laser — and when you’ve remembered to keep an eye out for incoming fire, since you lose a life every time you take a hit, which means resetting your offensive capabilities when you return.

If you want to give yourself one less thing to think about, you can set firing to auto, instead of manual, so you can concern yourself more with where you’re shooting instead of when. And while the normal mode isn’t necessarily easy, if you feel you’ve mastered how the game’s systems work, and you want to see more enemies and more projectiles to dodge, well, the hard mode is right there for you then.

The last third of the game sees a real spike in difficulty, regardless of your comfort level, which is good from both a challenge point of view and from a narrative one: Gleylancer has an actual story, and as said before it’s told in-game by anime-style cutscenes. However, you can fail in the actual point of your mission and get the bad ending in the process, by failing to save your father’s ship from the enemies that keep firing at it.

You play as 16-year-old Ensign Lucia, and in the opening cutscene you discover that her father, an admiral in the Earth Federation navy, has been essentially abducted by aliens. His ship was warped out of local space and into unknown regions, and the Earth Federation does not believe they are in a position to launch a rescue even for someone as high-ranking as an admiral and his flagship, not when the alien forces so greatly outnumber and outgun them. Lucia learns of the existence of the experimental Advanced Busterhawk Gleylancer fighter, though, and with the help of a friend, steals the ship and heads off toward the last known position of the ship’s signal.

In stage 11 of 12, Lucia finally catches up to her father’s ship, and it’s under attack. Save it, and you get the good ending. Fail to save it, and, well, Lucia’s dad is dead. Good going, jerk. Since the game actually does a good job of introducing you to the central conflict of the game — a personal story within the larger story of Earth’s space being invaded by hostile aliens, and the ongoing war attempting to stop it — you might even hope that you save Lucia’s dad for more reasons than just it opening up the full, best version of the game.

These kinds of cutscenes in a shmup were not introduced by Gleylancer by any means — it annoys me to no end that the Japanese versions of Aleste games, which comfortably predate Gleylancer, have cutscenes and story that tie together across the series, but the North American versions just straight up got rid of most of that instead of localizing it — but it’s fun that these are about more than just showing you a cool visual of the ship you’re piloting and the person piloting it, too.

The last thing Gleylancer really has going for it, outside of the mover system and a shmup story, is the soundtrack. It’s really an excellent example of Sega’s FM Synth sound hardware used right. The music is driving, it’s persistent, and it’s catchy, which is perfect for the genre. There’s nothing like tapping your foot and nodding your head along as you hyperfocus in on enemy ships and projectiles you’re trying to avoid, and Gleylancer’s soundtrack certainly allows for that. The whole thing is great, and I’ll share the whole soundtrack below, but I kicked things off with the song that plays during the opening cutscene not just because it’s at the beginning, but also because it will give you a great idea of what you’re in for, audio-wise, in Gleylancer.

I liked Gleylancer plenty before it got a re-release, though, it was always a shame I couldn’t know exactly what was being said in the cutscenes. It’s had a bit of a mixed reception over the years. People loved it or weren’t moved by it in the slightest back in its initial release, and outlets like Eurogamer basically shit all over it when it released on Virtual Console years later. I’m a big fan, though, and the latest re-release has only reemphasized that for me.

The modern release of Gleylancer adds quite a few new tweaks that make an already great shmup even better. For one, it’s finally been adapted for modern controller design. You can play the original way still, with the directional pad controlling the movement of both the ship and the movers, and you holding down a button in order to lock the movers’ firing angle into place as needed. Or, you can use the right stick for the movers, and the left stick/D-pad for the ship, creating a feeling that I can only describe as akin to someone having grafted a twin-stick shooter into a horizontal shmup. Everything clicks into place so much quicker now playing this way, and while I’m not about to say I can’t go back to the old setup, I now don’t have to, and probably won’t. It’s all just so much more fluid and precise!

Ratalaika Games’ modern re-release also includes a rewind feature, which, listen. I love a shoot-em-up that hates my guts and wants me to fail. I love plenty of shoot-em-ups that lack checkpoints and force me to start a stage over from the beginning (and I love plenty of shmups that do have checkpoints even if those checkpoints screw me over from an arsenal-building point of view). I also think every single shmup should have a rewind button for when I’m not in the mood for that kind of self-inflicted abuse. It’s not like they keep you from having to figure out how the game works: you simply rewind and then still have to successfully manage whatever it is you just failed at. And no one forces you to use rewind, either, so if you don’t like it, don’t use it. Sometimes I feel like fully challenging myself, and sometimes I just want to pretend I didn’t get hit by that one projectile I had failed to spot before it collided with my ship. Rewind as an option allows for those feelings to coexist, and I’m glad this updated Gleylancer includes it. This has been my November contribution to The Difficulty Discourse.

Gleylancer was something of a lost or cult classic anywhere besides Japan for some time, and it didn’t necessarily get the love it deserved when it released worldwide on the Virtual Console, either, owing to both the density of shmups on that market and its lack of English cutscenes. We’re in enough of a shmup renaissance these days, though, for people to be able to take a step back and appreciate what Gleylancer did — and still does — differently than other shmups on the market. It’s the cheapest its ever been in its new format, and also the most playable and enjoyable, too. If you’re even casually interested in the genre, Gleylancer is going to be worth your time.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.