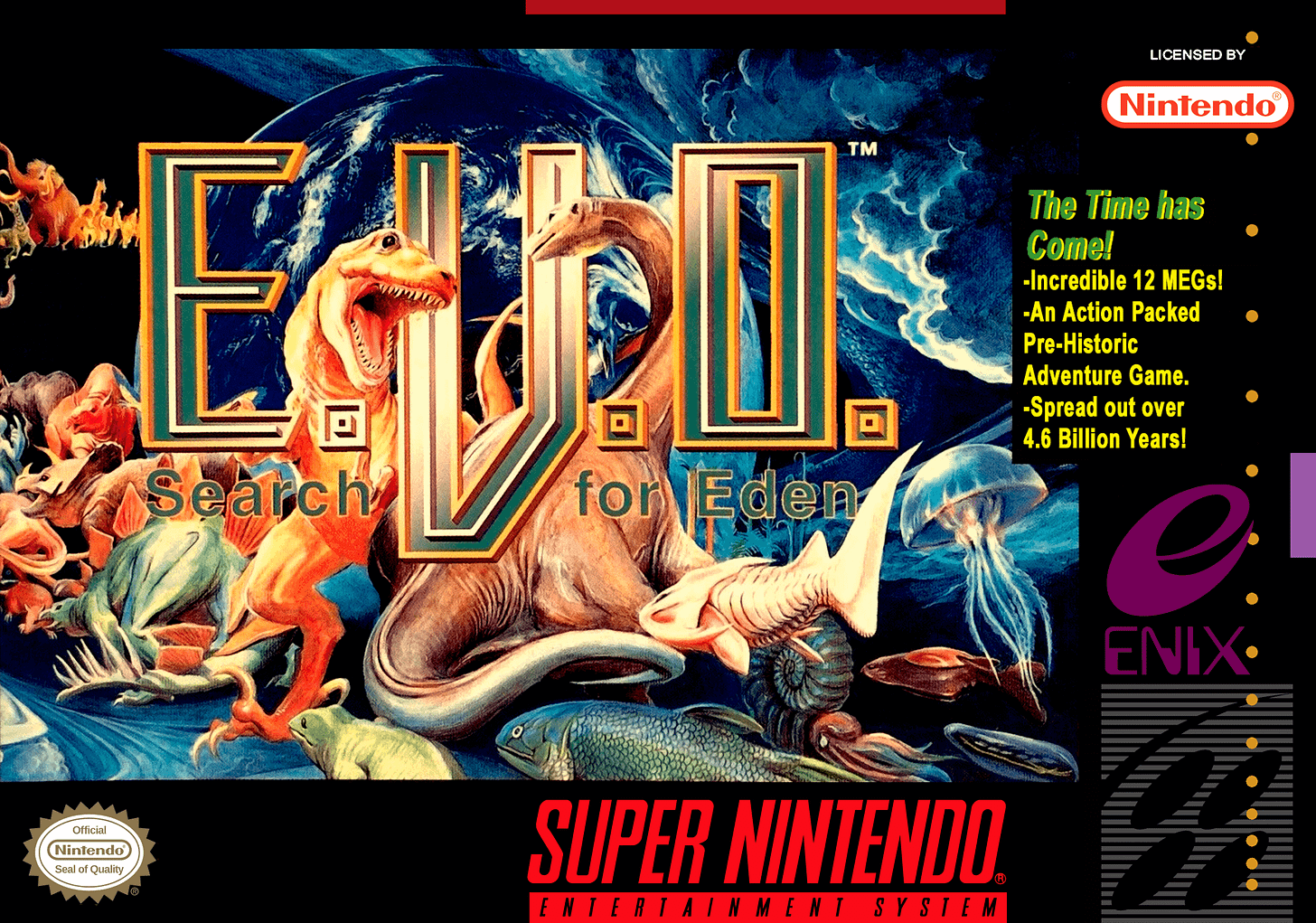

Re-release this: E.V.O.: Search for Eden

Not everything in E.V.O. works like it should, but it's still a fascinating experiment that deserves a second chance. Or third chance, as it were.

This column is “Re-release this,” which will focus on games that aren’t easily available, or even available at all, but should be once again. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Sometimes, we focus a little too much on every single bit of a game working in order to praise it. This quest for frictionless experiences can get in the way of playing some good and worthwhile ideas contained within games that aren’t up to par in one way or another. E.V.O.: Search for Eden is far from a frictionless experience: collision detection is often a mess, the story and themes aren’t quite as put together as you’d like, and the music veers between good and grating. Its main draw, though, is its central conceit: messing around with what is called evolution in-game, but is in reality more like contextual evolution in conjunction with user-controlled intelligent design.

There are elements of evolution in E.V.O., yes, but you’re also searching for literally Eden in order to live in harmony with the daughter of the sun, Gaia, forever, so of course there’s a bit of religion baked in here, too, and not all of it necessarily from the creationism/intelligent design pipeline of Christianity, either. “Mysterious” powers can rapidly change your appearance and species instantaneously, while a higher power also has control over your ability to return from death. Some of that is just for the sake of speeding things up — you don’t need to be a fish anymore and do need some legs once you make landfall — but other times, it’s Gaia just going, “hey it’d be much more convenient if you were a dinosaur now for this next part.”

Now, you don’t need to be a proponent of intelligent design — the vibes-based counter-theory to evolution — to think that the gameplay system of E.V.O. is worth checking out. It’s undeniably fun to experiment with changing the body or jaws or legs of a fish, amphibian, reptile, whatever, in order to set yourself up to survive the ordeal in front of you. Which, per Gaia, is a real survival of the fittest test throughout hundreds of millions of years of pre-history. She wants you to live in Eden with her forever — a decision she makes when you’re a fish. But before you get there, you’ll have to survive the waters, the land before plant life could change it for a wider variety of species, against dinosaurs, an ice age, and among early man. I’m not sure whether to make a joke about age gaps or The Shape of Water here, so I’ll just leave that up to you.

E.V.O. was completely new to North American audiences, but developer Almanic’s most memorable SNES output wasn’t the studio’s first foray into this world. In Japan, the game is actually known as 46 Okunen Monogatari: Harukanaru Eden, and is part of a series that began with 46 Okunen Monogatari: The Shinkaron. Translated, that comes to 4.6 Billion Year Story: The Theory of Evolution. One key difference for the Japan-exclusive PC-88 release that proceeded E.V.O. is that it was a turn-based RPG that was heavy on the text and story elements: its followup is lighter on both, with action and platforming the emphasis instead. As it’s a PC-88 game, it’s not one I can speak of in detail beyond this — someday, when I get both an emulator working well and more unofficial translations appear — but for the curious among you, Hardcore Gaming 101 has you covered.

The most significant change between the two other than the genre switch is that, in the original, you fed your experience points (known as Evo. Points in Search for Eden) into specific categories, similar to so many other role-playing games: strength, stamina, resistance, and intelligence. In E.V.O., though, you use those points on specific body parts not only to make them stronger, but with plenty of customization to consider, too. You can evolve your creature’s jaws, but which jaws? Are you selecting a moderately effective set of teeth and jaws with which to use them so that you can have plenty of points leftover for a tougher, more resilient body? Or so you can focus on adding in horns to ram enemies with? Maybe you’re looking to jump higher so you can attack enemies from above, so there’s a need to balance your spending in order to be able to both jump and bite before foes can react to your attacks.

Not every body part is available to evolve in each time period — your hands and feet are your hands and feet in the era of the amphibians, for example — but you’ve got plenty to work with each time out as is. Jaws, horns, neck, body, hands and feet, dorsal fin, tail, back of the head. Within each is a list of changes you can make, often based on characteristics of existing creatures, allowing you to Dr. Moreau your way through history with less mess than on the island. There aren’t many amphibians out there in nature who were armor-plated with powerful jaws and an ability to leap high into the air with what look like dragon wings attached, but you can make it happen in E.V.O. with the right evolutions. And in the same game in which you eventually get to mess around with mammalian physiology! Don Bluth rejoice, you don’t even need to be a human in order to get into heaven in E.V.O.

The one thing is that, regardless of what you focus your evolutions on, you need to make sure you’re also focusing on being as strong as possible in that arena. Otherwise, good luck defeating any of the game’s bosses, as they all hit exponentially harder than any standard enemies you find throughout the game’s many (short) stages. It’s pretty easy to tell what’s stronger, at least — if the names don’t give it away, the price in Evo. Points will. You can make some basic upgrades to your amphibian creature, for instance, for a few hundred points each, but to get the strongest body armor that’ll help you defeat the King and Queen Bees that are ruling over the land with iron… stingers? It’s going to run you 5,000 of the things. You can also increase your size or decrease it, depending on your needs.

All of these changes feed into stats that you can review, of your max hit points, attack power (Biting, Strength, Kick, Strike, Horn), defensive power, agility, and jumping ability. Mixing and matching to get a good balance is key — being powerful but too slow to do anything with that power is bad, and being nimble but too weak to make a dent in your foes is its own problem. It’s important to realize, though, that some things are going to be incompatible with each other, and new additions will override the old, causing you to have essentially wasted your Evo. Points. Maybe you can’t have a specific body while also having a specific set of hands or feet, or you’re in the age of the dinosaurs and need to choose what kind of dinosaur you’re going to be, and therefore what you’re going to have an advantage in. Fish might be fish, for the most part, but you’ve got dinosaurs walking on two legs and others on four legs, and they are going to have very different strengths and weaknesses to consider.

All of this customization and experimentation is both the meat and the draw of E.V.O., and also the reason to persist through its issues. Collision detection really is a mess: enemy attacks and contact take priority over your own while it’s very easy to be stunned, which means you can basically pinball back and forth between two enemies who aren’t even attacking you but are making contact with you until your health drains away, if you aren’t careful. The threat remains even if you are careful, of course, and persists thanks to decisions like allowing you to bounce on multiple enemies, but only once per jump: so you can successfully sneak up on a foe by jumping on them, then bounce to another, but you’re now open to their attacks while in the air until you land. And if you happen to land on them as you come down from that first jump, it’ll be you taking damage and getting stunned.

There’s also that you are sometimes going to need to grind due to the sheer power and health of the bosses you’ll face, and that’s a pain since there are some regions where enemies just aren’t giving you much for defeating them. Even the mid-world bosses are rough if you don’t take the time to both armor yourself up and find a way to excel in at least one kind of attack. Which results in you getting tons of Evo. Points from these bosses that you don’t really have a use for, since you already had to gear up, as it were, to face them in the first place. At least there is one potential use for these “extra” points, which is to change something unimportant about your creature’s body mid-fight in order to regain your hit points: it’s that or lose half of your current Evo. Points if you happen to die in battle, so you might as well make the occasional inexpensive aesthetic change just to refill your health.

There also isn’t as a tight of a narrative or as cohesive of a world as there is in something like Lack of Love, which also features evolution but does so in a very thoughtful way with both gameplay and narrative tied around the idea of working symbiotically with and within your environment. E.V.O. isn’t concerned with that sort of thing — again, your goal is to show up in Eden to hang with god’s daughter forever — so you spend a lot of time murdering anything you can gain experience from in order to achieve said goal. It doesn’t make it a worse game, necessarily, it’s just something to point out if what you’re looking for is different than what’s on offer here.

The soundtrack is good, except for when it is not. It was composed by Koichi Sugiyama, who you know better from, oh, all of Dragon Quest: the best tracks are apparently arrangements of songs found in E.V.O.’s predecessor, and the others are… worse. The songs themselves are decent in a vacuum, in the sense the sounds are not bad sounds, and there are catchy hooks to some of them. The problem is that they’re very short, like someone decided that, because the SNES’ sound chip was designed with very small and short samples in mind, that those short, 64 kilobyte music samples were themselves entire songs. Instead of stringing together a whole bunch of 64KB samples like Yuzo Koshiro did for ActRaiser, for instance, to create these layered, impressive compositions that went beyond the basic abilities of the tech, E.V.O.’s soundtrack mostly satisfied itself with the same little clip playing again and again and again on a loop until you finish the level or lose your mind.

So, you end up with something layered and appropriately haunting and beautiful with the theme for the ocean, which is an arrangement from the first game in the series…

…as well as this from Chapter 3, which you were released from the prison of only when you entered into a short stage that had no music at all:

That’s the whole thing. Again and again, throughout a game world. Too many songs on the soundtrack are like that, which balances out the good stuff in the wrong direction.

All of that being said, as pointed out before, it’s still worth checking out E.V.O. for what it does with modifying creatures and letting you experiment with them in the game’s many short stages and multiple chapters/eras. It’s not a perfect game, not even close, but it tried something ambitious and intriguing that hasn’t exactly been replicate again and again in the decades since. It’s basically a perfect candidate for something like the SNES portion of Nintendo Switch Online, since you can dive in and come back out without having to commit to the full price of a physical copy of the game. But it’s also an excellent candidate for a remake that hews closely to the original spirit of the game, and spends its time fixing the collision detection, trying to enhance the soundtrack, things like that. It doesn’t need to be expanded or greatly changed or made frictionless: it’s just a game with a great central hook and idea that needs a little bit more support from the rest than it got nearly 30 years ago. As is, though, E.V.O. is still worth checking out, at least to get a sense of how well the one thing it does supremely well works.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.