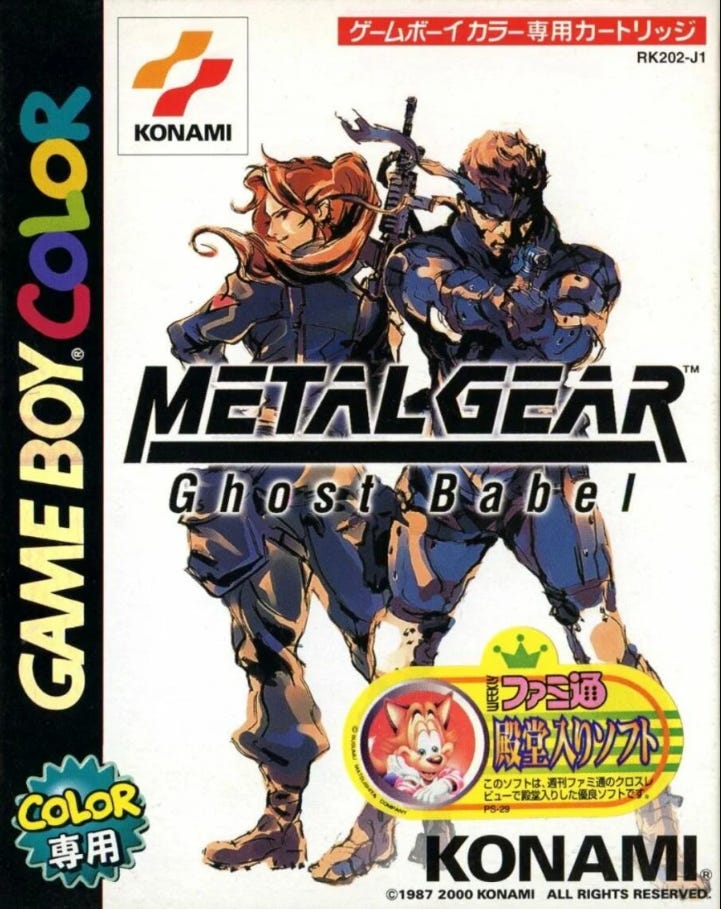

This column is “Re-release this,” which will focus on games that aren’t easily available, or even available at all, but should be once again. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

If Metal Gear Solid was the series' The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time equivalent, as both a translation of the 2D franchise into 3D as well as an expansion of its ideas made possible by both experience and new tech, then the Game Boy Color’s Metal Gear: Ghost Babel is its Minish Cap equivalent. The 2000 game, known simply as Metal Gear Solid in North America despite how confusing that is for everyone, ties the past and present of the series’ seemingly on-the-surface disparate forms together to show they can inform each other, that one version is not inherently better than the other, that they can feed each other. The result is something both new and familiar, the creation of a game even more ambitious than what came before that shows 2D games had far more left to offer than the massive rush to stick to 3D had suggested.

It’s a synthesis we still see with things like Metroid's return to side-scrolling in the present-day, Nintendo’s revival of Link's Awakening that leaned on the day’s tech to change the form but without changing the function of the title’s Game Boy roots, the wave of games inspired by or spiritual successors to Castlevania, Mega Man, the modern wave of Metroidvanias that the proliferation of indies and digital distribution have brought on, and so on. The accumulated knowledge of the various game types can crossover with each other just fine, and Ghost Babel was a shining example of that over two decades ago.

Ghost Babel feels like a game where someone who had played Metal Gear Solid went back in time to the MSX2 days and the origins of Metal Gear to say, "Hey, did you consider this?" Despite existing on the 8-bit Game Boy Color, it’s loaded with the mannerisms of a Playstation game: Solid Snake can now perform wall hugging, shift the view while doing so to see if the coast is clear, rap his knuckles on the wall to draw attention, and perform everything through animations that simply did not exist in the previous top-down, 2D Metal Gear titles on the MSX2. In addition, the kinds of changes to the 2D form that were made in the decade between Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake and Ghost Babel also make this title feel like more than just a return to an older form. The screen scrolls, instead of each piece of the map being one single screen that flips to the next — especially fascinating to see since that was something of an original Game Boy design staple — and Ghost Babel introduced movement in eight directions as well as diagonal firing. Most impressively, though, all of these changes to the original formula that found their origins in 3D Metal Gear and through advancements in 2D games over the years feel like they always should have been there in top-down Metal Gear to begin with.

None of that was an accident, of course: it was the point. Series creator Hideo Kojima was quoted saying as much during a roundtable interview published in Konami’s official Perfect Series guide:

It was a strange circumstance, but we received an order from a foreign distributor [Konami Europe] to make a Metal Gear game for the Game Boy. Metal Gear Solid on PlayStation sold around 5.5 million units The response was particularly amazing in Europe, where there a lot of passionate fans.

To tell you the truth, I didn’t want to do it at first. But up until that point we made games on several platforms such as the 3DO, Sega Saturn, PlayStation, PC Engine, MSX and the PC-9821, but not on the Game Boy. On top of that, another factor that I thought presented a good opportunity was the release of the new PlayStation 2 console, which is on everyone’s mind right now. In the age of hardware with multiple functionalities, more advanced technology is required even in the field of video game development, but by developing a game on a primitive hardware such as the Game Boy, I thought I would go back to my original intent and rethink what a game means.

Kojima only served as a producer on Ghost Babel, rather than in his usual position as someone involved in every part of the design process — directing, writing, design, etc. He was involved enough to be part of the decision about what the game would be, though, as evidenced by the above quote, and from there, some other series’ regulars — character designer Ikuya Nakamura, artist Yoji Shinkawa, and Tomokazu Fukushima, who wrote the Codec conversations in Metal Gear Solid and would do so again in its first two sequels — along with contract studio Tose took the lead. Shinta Nojiri was the director, and while he was part of the Konami crew, Ghost Babel was actually his first Metal Gear assignment: he’d end up working on Sons of Liberty, Snake Eater, and Guns of the Patriots, while designing, planning, and directing the two non-canon Metal Gear Acid spin-offs on the Playstation Portable. So it’s probably safe to say everyone involved was pleased with the job he did on Ghost Babel in Kojima’s place.

Like the Acid games and Portable Ops, Ghost Babel isn’t canon, instead taking place in an alternate timeline seven years after the original Metal Gear’s story. Much of the setup is the same as Metal Gear Solid’s, in that Snake is retired and living in Alaska, and then he gets a call because a shadowy organization has risen from ashes Snake’s former team helped to spread, and they’ve got themselves a Metal Gear. Ghost Babel takes place in Africa, and its story brings together Outer Heaven, FOXHOUND, Metal Gear, a local revolution aiming to push the colonizers out, and the kind of antagonists and characters Metal Gear Solid fans would have expected to see after experiencing that title on the Playstation. Incredibly enough, Tose and Konami pulled that off: it’s not just in the gameplay that things were borrowed from Metal Gear Solid, but Shinkawa’s artwork that was such a huge part of the visualization of Metal Gear Solid on the Playstation is given space to shine in the Codec, in lightly animated cutscenes, wherever it could successfully be placed in Ghost Babel, and the writing is also top-notch for the series.

First, the art:

The Game Boy Color was capable of this kind of presentation, but even if you played games on that system, you might not necessarily have been aware of that, depending on what you were spending your time with. Ghost Babel is one of the finest examples of what that handheld could do, though, and it was much more than just “Game Boy-caliber games, but now in color.” This is all art that would have been wildly ambitious and impressive to produce on the 8-bit NES. In fact, a well-known developer nearly went bankrupt doing that very thing. And there are also elements of the game that didn’t exist on the Playstation: Snake’s limb movement (as with the rest of his movement) is inspired by how he moved in Metal Gear Solid, but his bandana moves with every step he takes, too, which is new:

Possibly it was easier to do this kind of animation with sprites than with the much newer and more basic form polygons took at that point — please think of how long it took for hairs on anyone’s heads to move or react to any stimulus in 3D — but still, the desire to do so was necessary, and effort had to be put in all the same. It’s all part of the splendid animation of Snake’s limbs and body that carried over from Metal Gear Solid, and then was taken a step further, which is basically how this whole game operates.

From an audio perspective, Ghost Babel is also fantastic. The soundtrack was composed by one Metal Gear veteran, Kazuki Muraoka, and another composer who would become one in Norihiko Hibino. While Ghost Babel was Hibini’s first Metal Gear — and first video game composition at all — he would go on to work on Sons of Liberty, The Twin Snakes, Snake Eater, Guns of the Patriots, as well as collaborating on the first two Bayonetta games, Yakuza 2, and more. Muraoka, on the other hand, worked on the soundtrack for the NES version of Metal Gear, composed Metal Gear Solid, then was a sound director, editor, or supervisor on the rest of the mainline games in the series. Ghost Babel is full of arrangements of past themes in its VR Missions — yes, they found room for VR Missions even in a Game Boy Color cartridge — as well as new music for the campaign, and it’s all exceptional, and makes excellent use of the platform’s sound hardware. The Maintenance Base theme is perfect for sneaking around where you’re not supposed to be, which, you know. It’s Metal Gear:

And Reminiscence manages to help convey the emotional weight of the scenes where it’s utilized — in conjunction with the art and the writing, it all manages to create a whole lot more emotion and pathos than you might have been expecting from a game on a platform whose logo includes the word “color” written in the stylized font it is:

The writing is also more than you’d expect from a Game Boy Color title — hey, Nintendo systems were stuffed with killer games at this time, but those games also had a reputation, fairly or not, as being for younger audiences while Sony catered to the generation of gamers who had already grown up on Nintendo platforms. That Metal Gear Solid was rated M by the ESRB but Ghost Babel got an E rating is pretty funny to consider: sure, it’s maybe a little more cartoonish in its violence than the more realistic depictions (for the time) that Konami went for with Metal Gear Solid on the Playstation, since we’re talking sprites and not polygonal representations of people here, but this is still a game that deals with racism, imperialism, the United States’ hegemony and how far they’re willing to go to maintain their presence atop the world, Snake’s legacy as this hero killer of his own father and what it means to the world and to himself, and also a guy setting himself on fire on purpose. It’s a more mature title than your standard E for Everyone experience.

Most importantly, it feels like Metal Gear, and the kind people who had already experienced Metal Gear Solid would have expected following it. All of this despite being on the “primitive” Game Boy Color. What a great little system that too many people have forgotten is full of bangers.

Ghost Babel employs a stage-based structure that was new to Metal Gear at the time, but was also utilized in non-canon Portable Ops and the canon Peace Walker. There are 13 stages of varying lengths, and through this somewhat constricted form of play that cuts off past portions of the world as you leave them, it actually serves to make the game feel bigger than it would have otherwise. How large would Ghost Babel have been if it were actually fully open, if it wasn’t partitioned off into these smaller sections that you were meant to explore up and down since you might never get a second chance to do so? Replicating a larger, open world is difficult on less powerful hardware, but the right design decisions can help you fake it, or at least make it seem like an unimportant thing to do. As it is, Ghost Babel manages to include a number of varied environments — woods, farms, base exterior, sewers, base interior, warehouses, labs, hangars — and does so because the stages will focus on those areas one at a time, often changing up your goals and how you might need to approach a situation because of the changing environments, too.

The guards are smarter than they were in the previous top-down Metal Gear titles, and they also work together in a way that’s bad news for you to maximize their line of sight and cut down on their blind spots. Dogs can sniff you out, cameras can spy your activity, gun turrets will cut into your health with their bullets… Ghost Babel really pushes the idea of making it through without setting off alarms, by punishing you significantly for tripping one: guards will attack you from both a distance and up close, and they’ll come from multiple rooms to find you. You have plenty of places to hide, and can get through the entire game without firing a shot at anything besides a boss or Metal Gear, and Ghost Babel seems to be designed to encourage that style of play. Hell, one of the bosses chides you for how many people you’ve killed to get to him by citing an accurate count, and after each stage you’re shown just how successfully (or poorly) your infiltration is going, with the body count being one of the ways it does so.

Boss fights aren’t particularly challenging, but they’re still excellent for the characters you’re fighting, and play a massive role in making the game’s story what it is. Snake learns what it is these people are fighting for, and how they got into fighting in the first place, and is forced to consider his own place in the world and what it means through these battles. Those he’s fighting aren’t all that much different than he is, and in a way, he’s responsible for who they are and what they’ve become. The how of all of that, you’ll have to play Ghost Babel yourself to discover.

Ghost Babel is a great time whether you set the difficulty on the easiest setting just to sneak around for a few hours and engage with the story, but you can crank up the difficulty and make sneaking around a ridiculous challenge, if you prefer. The stage select mode also allows you to replay the levels you’ve completed in order to aim for a better score, and there are also challenge modes for each stage, as well, which feature you as an unnamed agent playing through a VR recreation of Snake’s Ghost Babel mission, with more of the story revealed to you here as a reward for challenging yourself to, say, only defeat this boss with grenades, or clear a stage in a seemingly impossible short length of time. For all the content that’s here — there’s also a competitive multiplayer mode that requires a Game Link Cable — there’s something missing from the North America version besides the superior name. IdeaSpy 2.5 is a 13-part radio play-style story accessible from the Codec once you’ve already completed the game once, but it’s only in the European and Japanese versions of Ghost Babel. Oh, what could have been.

Tose only got a brief mention at the beginning of this feature, and part of that is because they’re enigmatic as always. We know they worked on Ghost Babel, which is not something we usually know about Tose: they’re purposely secretive about which projects they work on, and prefer, like Solid Snake, to simply exist in the shadows and do the jobs that need to be done. In an interview conducted with Game Developer (then Gamasutra) back in 2006, it was revealed they had developed or assisted in the development of over 1,100 games: obviously, they’ve made more since. The identity of the vast majority of those is unknown, but on occasion, we get a Tose game we know was made by them: Scarlet Nexus with Bandai Namco, the Starfy series with Nintendo, and Ghost Babel with Konami, which very well might be the most critically acclaimed game Tose has ever been the primary developer for: it has a 95.61% score at GameRankings.

Despite being in the discussion for the top title on its platform, Ghost Babel just kind of quietly faded away. It hasn’t seen re-releases — not even when Nintendo opened up the 3DS’ Virtual Console to Game Boy Color titles — and, as a non-canon offering, wasn’t included in Metal Gear compilations that brought back the MSX versions of the classic top-down Metal Gear titles alongside their 3D successors. Ghost Babel released 22 years ago, was a deserving hit with critics, and then just kind of vanished from consciousness. There’s no record of its sales history at any of the usual resource sites, even.

And all of that is a shame: Ghost Babel is excellent, the kind of game that should have inspired Konami to make more like it on the Game Boy Advance, to realize the need to blend old and new on the dual-screen DS and not just go for polygonal power on the Playstation Portable. Instead, it happened, and then was seemingly forgotten about in every way other than putting the Konami developers behind it into prominent roles on future Metal Gear titles. Ghost Babel doesn’t have the kind of legacy it deserved, not even close, but at the least, it merits a re-release. Whether we’ll ever see one is unknown, considering the frosty relationship between Konami and Kojima in addition to Konami’s whole weird deal when it comes to making their past available. But whether we will get a re-release has nothing to do with whether we should: Ghost Babel is overdue for a revival, and not just because it will cost you more than a Game Boy Color did to acquire a copy.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.

This’ll be one of the first carts I pop in my Analogue Pocket whenever it finally arrives!