Retro spotlight: Metal Slader Glory

The technology of the day made Metal Slader Glory something of a failure, with repercussions that led to the HAL we know today.

This column is “Retro spotlight,” which exists mostly so I can write about whatever game I feel like even if it doesn’t fit into one of the other topics you find in this newsletter. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Games don’t have to be bad to fail, you know. Sometimes they can simply cost too much, or take too long to develop, or the advertising and marketing wing of the publisher can spend so much money on the promotion of the game that, even if it does manage to sell decently, that spent budget cannot be recouped, and the release the game actually put the company into debt. Or maybe the production of the game required an expensive chip that existed in limited quantities, so even when receiving said chip at a discounted price, the accrued debt from the marketing and lengthy development cycle made it so that the money for a second run of the game couldn’t be found even when the first run quickly sold out.

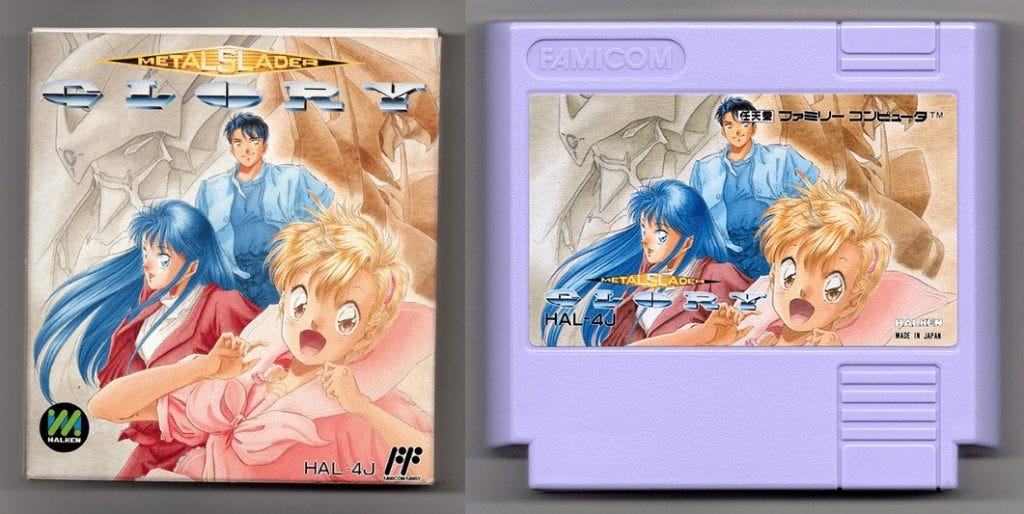

Or, as you can probably guess, all of those things can happen at once to one game, nearly dooming the publisher in the process. That’s the story of HAL Laboratory’s Metal Slader Glory, though, not all of the story, not for the game nor the developer who is very much still around 31 years later. Metal Slader Glory is far from a bad game — it’s a pretty good one, actually, that featured high-caliber art and a sci-fi tale set in a world you want to see more of — but the cost to produce it was simply too much for the technology of the time. Part of what made it stand out in the first place, and still stand out today, is also part of what led to its failure, and eventually, the shift of HAL Laboratory from an independent entity to a second-party developer for Nintendo.

The NES and Famicom were known for their pixel art, but there were workarounds that could allow talented artists and developers to create what looked more like anime-style art or even a cutscene. Think of the opening cinematic from Ninja Gaiden, with its larger, detailed sprites, especially when it zooms in on the faces of the two ninjas and their legs, the scrolling of the foreground — it’s a lot to have the NES be doing! Now, that’s just the opening scene, of course: there is room for that sort of thing on an NES cartridge should a developer want it to be there. If you want to make an entire game out of even more detailed artwork than that that is also larger and animates, you’re going to need to spend a lot of time creating that art, and your cartridge is going to cost much, much more to produce and sell. Which is basically Metal Slader Glory’s whole deal.

It was conceived, written, designed, drawn, and directed by Yoshimuru Hoshi, who was working as a contractor for HAL. As Hoshi himself told it years later in an interview Shmuplations translated:

When I was getting ready to present the game… well, I suppose you couldn’t really call it a presentation. It was an attempt at a design doc, a screen mock-up and a couple of example animations. But, while I was waiting to show what I’d made, I was testing it on the monitor and [Satoru] Iwata happened to walk past. He saw the graphics, and the game was given the go-ahead without the presentation. (laughs)

…

He didn’t tell me directly, but my colleagues told me later that he said the graphics looked more advanced than something a Famicom should be able to produce.

Yes, that Iwata, who would eventually become the president of HAL (while still working as a programmer!) and then move over to Nintendo, where he would be their CEO during the era of the Nintendo DS and Wii systems. At this time, Iwata was head of development for HAL, and he wasn’t wrong: Metal Slader Glory looks more like it belongs on one of the Japanese PCs of the time than it does the relatively underpowered Famicom. It wasn’t just that the art was in an anime style and featured heavily detailed characters in a variety of poses, armed with even more facial expressions. It’s that they also managed to be animated, and not just static portraits, and all back on a machine that didn’t have the ability to always play music and sound effects at the same time. It wasn’t just character animations, either: there’s a stunning-for-the-time driving sequence where a car is towing the titular robot, and multiple spaceship launches and bits of animated space travel, too.

Of course, Metal Slader Glory did have some help on the tech side: for one, HAL was just an absurdly talented studio on the technical side even back before they were famous for any one particular series, one capable of solving development problems and working beyond the limitations of the hardware. In the posthumous pseudo-memoir, Ask Iwata: Words of Wisdom from Satoru Iwata, Nintendo’s Legendary CEO, both Iwata and Shigeru Miyamoto discuss that part of the reason their relationship worked so well is that Iwata was a programming genius adept at pushing beyond the limitations of the hardware, while Miyamoto was something of a visionary for how things should play and feel and make you feel: Miyamoto even commented to Iwata on how, at one point in their history, HAL’s games were often technical marvels that were still lacking some last bit to make them truly great — remember that last item for later. Combined, the two were a force of directorial nature that filled in the gaps in the other, and shaped the Nintendo of the last couple of decades even before Iwata left HAL.

So, in short, the Famicom shouldn’t have been able to do what Metal Slader Glory did, but between the know-how of HAL and a specific chip added to the Famicom cartridge — the MMC5 — they were able to stuff this advanced art onto a system that just did not produce games that looked like this.

Metal Slader Glory is a visual novel/adventure, one that took long enough in development that the popularity of the genre had somewhat waned by the time of its release. It’s not that visual novel adventures weren’t still viable in 1991, it’s just that they were often starting to fill themselves up with more risqué content to gain attention, and were also basically a Japan-only genre at the time, as well. So, the market for Metal Slader Glory could have been there, at least locally, but the conditions of 1991 were a bit different than those of 1987, too, so it wasn’t without risk. Luckily for Metal Slader Glory, it certainly stood out for a Famicom title thanks to its art and presentation. Here’s what Nintendo’s own visual novel adventure, Famicom Detective Club, looked like in 1988-1989…

…and here’s what Metal Slader Glory looked like just a few years later:

It’s not the extra few years of advances in tech that made for such a massive difference: the art always looked like this, or at least was meant to look like this, but it was the act of actually creating it that took so long for Hoshi and HAL. As Hoshi described in the previously linked interview:

I’ll go into more detail about this later, but the Famicom hardware is tile-based and there’s a limit to the number of unique tiles the Famicom can display. If you were to add together what you can store for the background and sprites it would only take up about half the screen, so it’s not really enough to display large pieces of artwork. I think seeing those large characters blinking and moving their mouths on screen was what piqued Iwata’s interest.

…

There’s a limit to the number of 8×8 tiles you can store within a bank so the more parts you can reuse multiple times the easier your job will be. For large areas of the same colour, you can simply reuse the same 8×8 tile over and over again, but that doesn’t work for complex art, so you have to come up with more ingenious ways to solve the problem.

You should read the entire thing, but I’ll try to break this specific bit down. Basically, there is a limit to how many 8x8 artwork tiles you can store inside a Famicom cartridge, which creates difficulties for rendering complex, detailed artwork. It’s why so many backgrounds on NES and Famicom games are simple, or repeat, or are straight-up just solid colors: it’s to save the available 8x8 tiles for areas that requires more detail, and to allow for more variety. One of the more impressive technical aspects of the Super Famicom’s Tengai Makyō Zero (developed by Red Company and published by Hudson Soft) is that the game did not have a single palette-swapped enemy within it. Every single foe in this JRPG was a brand new creature, and they managed this trick with a similar cartridge-boosting chip that decompressed data in order to allow for far more of it to be stored on the cartridge.

If things like palette swaps and reused tiles as a workaround for limited cartridge space were still a problem to be deftly overcome during the Super Famicom era — and Tengai Makyō Zero released five years into that console’s lifespan — you can imagine how difficult it was to fit detail and variety into a cartridge from the previous generation. As the interviewer points out, Metal Slader Glory’s art was only possible because Hoshi “drew the art, converted it to pixel art and arranged the tiles [himself].” This would have been a ton of work if it were just static art we were talking about, but again, these large-scale characters also animated as they talked, as they reacted to what they were hearing or seeing, and so on.

There was actually so much art that it couldn’t all fit into the finished Metal Slader Glory, either, even with Hoshi’s four years of workarounds: much of it would not resurface until the redrawn Director’s Cut of the game was released as the very last title for the Super Famicom in 2000, and the intro portion of the story was actually confined to the original game’s manual as a manga. (Which, thanks to fan translators, you can actually read all of in English in the present.)

Four years might not sound like a lengthy development time in the modern era, no, but in the late-1980s and early 1990, four years was basically an eternity. Iwata himself is actually torn on Metal Slader Glory, given the fact that people love it, but it just took far too long and cost even more. In a 1999 interview with Used Games Magazine, Iwata went as far as to call allowing the game to continue development a “mistake” (translation once again by Shmuplations):

This game took a tremendously long time to finish. It’s actually kind of amazing that we stuck to it, persevered, and eventually released it, but from a management perspective it was a mistake.

…

Very few copies were produced and put in circulation—for that fact alone, I can’t really praise it. (laughs) On the other hand, there’s a lot of people that continue to love this game, and I think that’s due to all the energy and love we poured into its development. That’s something I can be very happy about.

Iwata is not exaggerating when he says that it was a mistake to continue development, at least from “a management perspective.” Again, the marketing and advertising campaign for Metal Slader Glory cost so much that even though the game sold through its first run in a hurry, there wasn’t any money available to buy more MMC5 chips from Nintendo for a second production run. And there might not have been enough chips available to help, either: as Waypoint mentioned in a story back in 2017, the extremely popular Super Mario Bros. 3 utilized the same chip and had been out in North America for a year already by the time Metal Slader Glory released, and the PAL region release of SMB3 was the day before Metal Slader Glory’s own. So it’s entirely possible that Nintendo had limited the number of chips for sale for the first production run of the game because they had other needs for it, too, and then when a second run was needed, HAL simply didn’t have the funds to acquire more.

Basically everything that could ensure that a second run wouldn’t happen occurred, but none of that takes away from the quality of the game. Reviews at the time were middling, but likely stemming from some confusion from the critics, too: while Metal Slader Glory is a visual novel adventure and pretty straightforward about that most of the time, it also features some menu-based “action” segments involving guns and robots, as well as a brief first-person dungeon-crawl. The game did nail these other styles, yes, but take a look back through some old reviews of games that tried to genre-blend like this, and you’ll often find some confusion over not being able to succinctly describe what you can expect.

It also went from a smaller, very character-driven story regarding some questions about what exactly this giant robot — the titular Metal Slader Glory — that Tadashi, his girlfriend Elina, and Tadashi’s younger sister, Azusa had ordered to use as basically a construction vehicle for their business on Earth was, to an attempt to solve the mystery of what everyone who could shed some light on that question was hiding, to a straight-up attack by shape-shifting aliens that you kind of accidentally began to uncover the inevitability of over the course of the previous few hours of play. None of it seems odd in the present, not the way the story shifts in its focus nor the changes in genre, but in 1991, it was all apparently a little much. And you have to remember, too, that it was on last-generation hardware, as impressive as it might have looked with that consideration in mind, so there were reviewers who were going to ding it just for that, as they had already fully moved on to a world where 16-bit consoles existed, in the same way a certain kind of critic from the next gen would get salty whenever a developer utilized sprites instead of polygons.

So, demand for a chance to play the game that just wasn’t available even when it was eventually led to the Director’s Cut, but, notably, it was only as part of the re-writable flash cartridge service the Super Famicom employed in Japan, the same one that allowed for a direct download of the SFC’s late-life Fire Emblem: Thracia 776 to a blank cartridge in a store, rather than having a physical release. The marketing was obviously lesser, given the Nintendo 64 was nearing the end of its life by 2000, never mind the Super Famicom. And this version was published by Nintendo, not HAL, since things had changed in their relationship since the original days of Metal Slader Glory.

It wasn’t just because of this one game that HAL was in debt, but spending four years on an expensive game that didn’t make back its marketing costs did not help with the publisher’s debt, either. In Ask Iwata, it’s revealed that, at the time Iwata took over as the president of HAL in 1992, the company had a debt of 1.5 billion yen, which was around $12 million at the time, and obviously more now after accounting for inflation. After the lengthy development cycle of Metal Slader Glory, HAL ended up rushing a few games to market in the hopes of making a quick buck to pay down their debt, and those did not sell particularly well, which meant the opposite occurred. The unconfirmed word is that this near-bankruptcy tailspin HAL found themselves in led to Nintendo infusing them with cash and making them a second-party developer — that is, one still capable of developing titles for other publishers and platforms, but is also incentivized to work on the platforms of the company that owns a stake in them — under the condition that Iwata was made president of HAL.

One of Iwata’s first decisions as president was to get rid of the marketing and advertising wing of HAL: instead, marketing of their games, and all of the associated costs, would now be left to whichever entity was publishing them, which, far more often than not, was Nintendo. The closer relationship also meant that Nintendo was there to advise HAL on their games, to help give them that last little bit that Miyamoto claimed was sometimes missing from their titles. Per Iwata himself in Ask Iwata, for Kirby’s Dream Land, that meant changing the name of the series from what it was going to be when the plan was to self-publish it — Twinkle Popo — and giving it a few more tweaks after Miyamoto told them “This game deserves more attention,” such as creating the more difficult second run after you complete the game the first time, were examples of that kind of advisement.

These were still HAL’s games, but now they had a partner to ensure that more people would be able to see just what HAL was capable of. Kirby’s Dream Land, by the way, has sold over five million copies worldwide since its release 30 years ago, and its success led to a franchise with 35.5 million in lifetime sales before official figures for the latest, extremely popular entry even exist. HAL’s development and talent is largely responsible for all of that, but given how the Metal Slader Glory situation went, don’t discount the benefit of having a publishing partner with deep marketing pockets and deep insights, either.

Metal Slader Glory is a game worth playing, with a surrounding story worth knowing, that did its part in changing the landscape for and the nature of the relationship between two major development studios. Neither Nintendo nor HAL has ever given it an official North American release, but the same group that localized the Famicom original’s manual also translated the entire game, which means you can emulate it in English and experience it for yourself. It’s around four hours long, and wildly impressive when you consider the context within which it released: that the game ever existed at all might have been a “managerial mistake,” but all this time later it’s hard to be disappointed with the results of either the game itself, or the row of dominoes its existence began to knock down. Let’s hope HAL and Nintendo give it another shot, for a worldwide audience, especially since Nintendo has already tested those waters with their own Famicom Detective Club remake.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.