Remembering Toaplan: V-V, aka Grind Stormer

Regardless of which name you're using, it signaled a change in Toaplan's shoot 'em ups, which would become fully realized only with the legendary successor studio, Cave.

Toaplan rose from the ashes of two other short-lived developers, and made a mark on the arcade scene of the 80s and early 90s. They were influential, they were innovative, they made the games they wanted to make, but they couldn’t survive the changing landscape of arcades, and shut down in March of 1994. Still, their influence continued both because of the games they had made and the games the branches of their family tree would go on to make, and Toaplan is now seeing something of a revival in many ways: all of this will be covered throughout the month of March. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

V-V — pronounced V-Five, as the second V is actually the closed-top Roman numeral for five — is a game you don’t necessarily hear about much, even compared to other Toaplan shooters. It’s pretty easy to explain why that is, though. It had a Sega Genesis home port, but it was a pretty compromised one that couldn’t fully replicate the intense experience of the arcade original. The arcade version released outside of Japan is a fine shooting game; the one released in Japan is a great STG. It’s an important piece of shoot ‘em up history, but overshadowed by the very next STG that Toaplan would develop, which iterated on quite a bit of what V-V introduced while also holding the distinction of being a legendary shoot ‘em up studio’s final genre entry.

V-V is vital for what — and whom — it introduced to the video game industry, though, and it’s worth taking the time to reflect on a game that led to the game referenced above, Batsugun, that led to the manic shooter, to bullet hell. That led to the formation of Cave, and a subgenre that to this day thrives, and even permeates other genres at this point. You see, V-V was directed by none other than Kenichi Takano, one of Toaplan’s original six founders. Takano, post-Toaplan’s closure, would found Cave and become its president, while also working as a producer or executive producer on the initial releases of loads of their games, as well as their present-day re-releases on modern platforms.

While most Toaplan shoot ‘em ups were programmed by composers Tatsuya Uemura or Masahiro Yuge, V-V was the domain of a pair of newer employees, Seiji Iwakura and Tsuneki Ikeda. It was the first game credit for either programmer, and while Iwakura would end up with just a few more credits post-Toaplan, Ikeda is a household name. Well, in niche households, anyway. Ikeda would work on V-V and Batsugun for Toaplan, then join Takano at Cave, where he’d be the programmer for DonPachi, DoDonPachi, ESP Ra.De, Guwange, Progear, DoDonPachi: Dai-Ou-Jou, Ketsui Deathtiny, Mushihimesama… I could keep going, but the point is that Ikeda programmed practically everything Cave produced from the moment he joined, and Cave’s output is as meaningful to the history of the genre as Toaplan’s own, or that of any other studio. He also served as director for quite a few of the games he programmed, beginning in 2002, and has continued in both roles for the modern re-releases, as well, with a few supervisor credits thrown in.

More on Ikeda’s very obvious-with-hindsight role in V-V in a bit, but first, there’s more notable credits to discuss. V-V is also the first credit for artist Yusuke Naora. He’d leave Toaplan for Square, joining up with them in time to serve as a Field Graphic Designer for Final Fantasy VI. He was a graphic designer for Front Mission and once again on field graphics duty for Chrono Trigger, and then became the art director for Final Fantasy VII and VIII, and the art director for the “world” graphics of Final Fantasy X. He continued to work on the art, in one capacity or another, for the various Final Fantasy VII spin-offs like Dirge of Cerberus, Crisis Core, and Before Crisis, worked on Final Fantasy XIII, on Type-0, was an art director for Final Fantasy XV, and still does freelance work for Square Enix on occasion even after leaving the company. That’s a hell of a résumé, and the work he pointed to in order to get that first gig at Square was V-V.

Throw in that Yuge contributed a soundtrack up to his usual standards of quality, and V-V’s credits are something else to behold. It was a bunch of new hires and someone as integral to the company as Yuge, and what ended up being produced managed to show appreciation for what Toaplan had been for nearly a decade, and what it would have become had it continued to exist rather than close one year later.

While doing press for V-V, planner and public relations person Iwabuchi Koetsu explained that, “We plan to continue to release arcade STG games that both preserve Toaplan’s signature style while also bringing something new to the genre. For both new and old players, I think the way people enjoy STGs is changing. We want to pursue those changes, and while we don’t intend to stick only to vertical shooting, we want to continue making truly fun games that can fairly be called top tier STG.” They’d only get the one more STG post-V-V, but the various offshoot studios that came out of Toaplan’s closures certainly produced a mix of games that went in this direction of blending the old and the new together, with a focus on more hardcore, niche players due to the shrinking mainstream popularity of the genre.

Ikeda is a bit lucky in terms of where he ended up getting his first gig in the industry. Toaplan wasn’t hierarchical, with an approach where basically anyone could pitch their ideas, and everything would go from there: you didn’t have to be Uemura or Yuge to have a game made, you just had to be able to come up with a killer idea that could field a development staff of people excited to make it with you. Ikeda has even stated that this was a formative experience for him, such as in this 2004 interview about his career, translated by Shmuplations:

Since it was my first game, I have a lot of memories of V-V. When I joined Toaplan, it was my first experience developing games in an environment where everyone was a “colleague;” that is, there was very little of the typical hierarchical relationships you find in offices, so if you had an idea you wanted to push, you had to convince everyone with words and logic instead of deferring to authority. By repeating that process day in and day out, you got to see your own ideas and thinking in an objective way, and realize how narrow and one-sided your conceptions might be. It was then, working on V-V at Toaplan, that I learned you couldn’t just assume that the player was going to see things in the same way as you, the creator, did.

In the aforementioned press interview, Ikeda also said, “For our games, we all contribute to the initial game design plans, and there was a lot of fighting about that. It was tough in the beginning, not knowing who would back down.” Toaplan designed arcade games that were difficult, yes, but they also wanted players to be able to see what the idea behind the game was, to be hooked by it and feel like it was worth stuffing more quarters into. If they couldn’t understand the why or the how of a game, they would move on to the next one. Ikeda not only was able to even program the kind of game he wanted to despite it being his first project thanks to Toaplan’s structure, but learned more about the creator-player relationship, and how to bring the latter around to the ideas of the former. Considering how complicated the systems of Ikeda’s games would become over time with Cave, that’s an important thing to discover, and he did so as early as you can in your career: at the beginning.

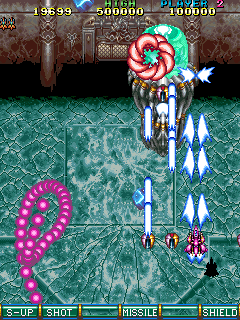

Ikeda would also explain, directly, the kinds of changes he implemented in V-V compared to previous Toaplan shooters. “It has autofire. (laughs) Also, until now Toaplan STGs have had fast enemy bullets, but this time we slowed down the bullet speed but increased the onscreen bullet count. So you can enjoy the thrill of dodging and the sensation of rapid fire.” Those are massive changes: previous Toaplan games didn’t necessarily need autofire, given the way they were designed. Enemies could come in waves, but it was about picking off individual, low-health enemies with a quick and accurate trigger finger, and then slamming on that button repeatedly against bosses to drain their health while dodging quick but relatively uncomplicated bullet patterns. There were tweaks made to the design over the years, like Vimana making enemies far stronger than usual, or Dogyuun introducing some new ideas that changed how you approached things while upping both the bullet and enemy counts without slowing either down, but Toaplan mostly had a core strategy to build off of, and stuck to it.

Until V-V. The slowed down bullets might make it all sound easier to someone unfamiliar with how manic shooters, bullet hell shooters, danmaku shooters, whatever you want to call them, work. But the bullets are slower because you’re supposed to extrapolate from their position and movement where they’ll be when they finally reach your ship, and place yourself in a safe space. Except it’s not as easy as that, because enemies, especially bigger, more powerful ones, in manic shooters tend to fire off more than one kind of projectile at once, each with their own movement patterns, so it’s about reacting to multiple kinds of bullets at once, and not all of those projectiles are going to move slowly, either. The bullet curtains, yes, but missiles, lasers, and so on, those might still be going the more “traditional” speed, and you have to account for them when choosing where your ship must be as the bullet curtain draws near.

Ikeda didn’t mention it in the interview, but the hit box — the area in which, if you’re hit, you will actually suffer damage — for the ship in V-V is also much smaller than it is in other Toaplan STG: the idea is what it always is for bullet hell, in that everything you’re doing always looks and feels more impressive than it really is, but it’s also damn impressive to begin with given the number of bullets we’re talking about maneuvering around here. Toaplan began their legendary STG run with a hit box that was an entire helicopter, and by the time they were done, hit boxes were a small area contained in the center of the ship. Toaplan’s hit boxes certainly weren’t as small as what Cave would eventually utilize, but anyone familiar with Toaplan’s older work knows the dangers of enemies crashing into your ship from below or the sides when you don’t see them. In V-V, depending on where the ships hit you, all you might notice is that hey, you’re not dead: it must have just missed you after all. It did, but only in the sense that it didn’t collide with the smaller-than-usual hit box.

With enemies coming from all directions, and aiming maybe not a thing you can always be doing like in previous Toaplan STG, autofire became a necessity. There’s still more to it than just holding down the button, however. You have three different weapons to choose from in V-V, and each plays so differently that, as you become familiar with how the game is laid out, you begin to understand that certain weapons fit different situations better than the others. The basic “Shot” is a wide beam with options firing outward at an angle, while your primary beam is focused forward. It’s helpful for large swarms of popcorn enemies — that is, weaker, easy to destroy ones that try to overwhelm you mostly with numbers — coming from multiple sides, but is a little weak for foes that can take a beating before exploding. If you move your ship backward without firing, however, the options close in to where your main beam is, and you can now fire a focused, exceptionally powerful laser that lacks horizontal range, but can basically melt enemies. This is very much the kind of thing that would feature in Ikeda’s games going forward, with the addition of your ship slowing down while you use this powerful beam as a countermeasure to keep you from just laying down on the fire button in this mode forever.

The second weapon is “Search,” which has the options seeking out foes to attach themselves to. They basically look like little drills trying to punch their way through the armor of enemies in this mode, which can be useful in whittling down the health of tougher enemy ships, and also great for letting you focus the primary beam attack of Search where it needs to while your options are off elsewhere attacking another foe. Last is “Missile,” which seems a little weak at first compared to the obvious strengths of the other two, but once you’ve fully powered up this particular weapon, it creates a neverending wave of missiles that are fired off by four options, who move when you do but not with you, ensuring that, wherever you aren’t shooting yourself, there is a stream of missiles laying down cover fire. It’s excellent for when the number of enemies is the problem much more than their individual strength, but you can also manipulate the movement a bit to focus it on a single, large target as well.

As for how to pick up these different weapons — and how to power them up — we have to go back to Toaplan’s second shooter, Slap Fight. Slap Fight utilized a power-up bar that looked a lot like what Konami’s Gradius employed: you pick up an upgrade chip, and store a few of them until you reach the upgrade or weapon type you want to use. V-V’s upgrade bar is quite a bit like that of Slap Fight, but the game’s are significantly different: really, there’s no better comparison for the changes that had come to Toaplan’s shooters over time than the differences between these two titles, released eight years apart.

Slap Fight features enemy bullets that move faster than your ship even when it’s had its speed fully upgraded. There aren’t a ton of enemies, but they’re all ridiculously accurate with their shots. When your ship powers up, it actually gets bigger: the only way to truly improve your firepower is to grow in size by adding wings, wings that make it more and more difficult the more of them you add to fully avoid enemy fire. V-V, meanwhile, got rid of all of the ship size changing, slowed the bullets down while keeping the ability to speed your ship up repeatedly through upgrades — while also converting the Speed Up tab to a Speed Down one once you maxed out, in case you find you are now going too fast to control the way you want to — and changed the shield from a temporary power-up that you’d deploy at a specific time like a boss fight to one that you get to keep until you’re hit. The weapon systems are a bit more simplified overall, but in positive ways, like swapping out the wings mechanic that grows the hit box for a straight power-up that will change the size and strength of your attack by adding additional options, from the two you start with to four, in addition to strengthening the primary beam.

V-V isn’t a sequel or even successor to Slap Fight, so much as that Slap Fight was built around an underutilized system that could be brought to the present by this new-look Toaplan development team. It’s both the only thing like it (in the vertical, non-Gradius space), and a completely different experience than its inspiration. V-V limits how many extends you can acquire, with them coming only at 300,000 and 800,000 points, along with the rare one-up item you might find: this makes continuing on after the game’s six stages within its loops far more challenging than in other Toaplan titles, where the extends get harder to come by, but do keep coming. The enemy variety and behaviors are significantly different in these two games, the way you play is new despite obviously taking inspiration from Slap Fight: they’re unrelated, really, except for that one feature with the upgrade bar, in the same way that Gradius and Slap Fight are unrelated outside of that. Slap Fight has just as much in common with Data East’s B-Wings, due to the ship changing shape and size as it powers up, as it does Gradius, in the same way V-V really has more in common with games that didn’t yet exist than it does Slap Fight. The inspiration drawn from it, though, is also very clear: the options in V-V are even named “WING,” which seems like it’s certainly a nod to Slap Fight!

V-V was known as Grind Stormer outside of Japan, and everywhere but there, it’s a completely different game. Well, it’s the same game, in the sense it has the same enemies, layouts, weapons, the shield, the speed up, the power-ups. The difference is in how you get to any of those things: instead of the power-up bar from V-V, the various power-ups you find now just are those things, to be collected or not. It takes away some of the freedom and strategy and relative uniqueness of the game, and makes for a worse experience: it’s still great, but it’s not great: V-V is clearly the superior of the two. Which is why it’s good that the port Toaplan commissioned Tengen to produce for the Mega Drive and Genesis actually includes both V-V and Grind Stormer, so you can choose which version you want to play. The problem is that the port isn’t very illustrative of what made either game work, given that it came up against some hardware issues: consider that the next shoot ‘em up that Toaplan would release, also in 1993, would end up ported to the 32-bit Sega Saturn instead of the Genesis. V-V would have done better with a second attempt port to that platform, too, but by then, Toaplan was gone, and V-V was already a finished project, whereas Batsugun, at least, had an unreleased arrange mode that Toaplan successor studio Gazelle could include alongside the original in a port.

Here’s the good news: it was announced in late-March that Bitwave would be releasing V-V and Grind Stormer in a package deal for Windows, as part of their next wave of Toaplan shoot ‘em up releases. So you can not only experience the definitive version of the game, legally and without MAME, but you can see the differences between V-V and Grind Stormer yourself, and draw your own conclusions. And you’ll want to, because V-V is highly underrated, a game undone only by its inferior port and the superior game it helped to spawn, as well as the genre that grew out of the both of them. Batsugun is the first true bullet hell shooter, but V-V more than set the stage for it.

By the boss of stage 2, you can tell that V-V is much different than previous Toaplan shooters, even from their other early-90s output that pushed the bullet and enemy envelopes more than their 80s games did. By the boss of stage 3, when you’re dodging three kinds of projectiles at the same time while a fourth loops around the ship in an unpredictable fashion, you know for sure that this is something new not just for Toaplan, but the genre. And from then on, the screen is overflowing with enemies and bullets to the point of there even being some occasional slowdown that serves the purpose of letting you collect yourself and survive a maybe otherwise unsurvivable onslaught. It’s not quite bullet hell, not yet, but anyone going from this to Cave’s games, or from Cave’s to V-V, would be able to make the connections.

It helps that V-V isn’t just an important game, but also still loads of fun to play. It lacks some of the complexity of later, fully-realized bullet hell games, but this title also straddles the line between where the genre was and where it was going in a way that nothing else had. And how could anything else have, considering the driving force behind that shift toward a new subgenre for the hardcore fan came from the very developers that made V-V in the first place? It’s a title that makes you wonder what Toaplan would have kept making had they stuck around longer than the one year they had left after V-V — Uemura et al had made the games that Ikeda and co. had grown up on, and the latter had some different ideas about what the next wave of shooters should be, maybe different than the ideas the former had in mind, considering some of the post-Toaplan work of that group.

Maybe it’s for the best that things ended up dissolving in the end, in time for games like V-V and Batsugun to end up birthing a second Toaplan legacy, by way of a number of successor studios that helped shape the next decade of STG in the same way that Toaplan had the previous one. Still, it’s tempting to consider what would have come out of a studio that held on to all of that talent, together, in the non-hierarchical setting that created V-V and Batsugun to begin with. But hey, at least the future we did end up with resulted in the likes of DoDonPachi: Blissful Death and Battle Garegga and Mars Matrix. It’s hard to complain about that, and V-V was the first step towards it all.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.