Remembering Toaplan: Tiger-Heli

Toaplan's first shoot 'em up was a hit that set the direction of the studio from that point forward.

Toaplan rose from the ashes of two other short-lived developers, and made a mark on the arcade scene of the 80s and early 90s. They were influential, they were innovative, they made the games they wanted to make, but they couldn’t survive the changing landscape of arcades, and shut down in March of 1994. Still, their influence continued both because of the games they had made and the games the branches of their family tree would go on to make, and Toaplan is now seeing something of a revival in many ways: all of this will be covered throughout the month of March. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Tiger-Heli was not Toaplan’s first game, but it was their first shoot ‘em up, and the one that set them on the path that they’d stay on for the next nine years. Its existence also shouldn’t have come as a surprise, considering the history of the developers who created it. Toaplan’s initial roster of devs came from a pair of shuttered studios, Orca and Crux, which had made a few shoot ‘em ups in their brief existences. And one of those was a pretty direct inspiration for Tiger-Heli.

“Inspiration” being a specifically chosen word, since, despite the fact that some former Crux employees became Toaplan, Tatsuya Uemura, who worked for both companies, said there was little overlap between the development rosters for the two games. Still, the connection between Gyrodine and Tiger-Heli is undeniable, as both feature an attack helicopter back when there wasn’t an established lineage for that sort of thing, and for reasons beyond believing that controlling one would be fun. As Uemura put it in an interview with STG Gameside in 2012, “…because a helicopter is a slower craft than other planes, and it can hover in midair, we felt it really suited a shooting game where the screen was scrolling. In turn, I think that idea influenced us at Toaplan a bit.”

In 1984, it was still the early days of scrolling shooters. Namco’s Xevious had only arrived on the scene one year prior, and the initial wave of games that saw its genre-defining brilliance and used it as a blueprint were still arriving. Gyrodine was one such game, the debt it owed to Xevious clear. A vertically scrolling shooter with enemies in both the sky and on the land, with different weapons for taking care of either as needed. It also had its own thing going on, however, and wasn’t “just” a clone of Xevious with a helicopter instead of a ship. Rather than sci-fi, it was a realistic military shooter with enemy tanks and jets and choppers. And the angle of your helicopter as you flew actually determined where on screen it shot: you didn’t fire forward while moving left, you fired on the same trajectory as the nose of your craft, which angled with the direction you pressed in.

Tiger-Heli kept the slow-moving chopper, the accurate enemy shots that would be fired once their cannons or turrets or whatever were trained on your craft, and the military realism of Gyrodine, but ditched the angled shooting… sort of. As part of a series of changes, Tiger-Heli added options, known as “Little Heli” to the game. These fired either vertically or horizontally, and you could have two, one on each side of the chopper. They weren’t impervious to damage, like options usually are, but instead could be blown up in one shot. And since the width of your chopper increased with these Little Heli flanking it, and you were already slow-moving and basically always just avoiding being shot down in the first place… you’re going to lose quite a few Little Heli over the course of a run.

One other thing that Tiger-Heli retained from Gyrodine was the game’s publisher. Taito would serve as distributor for both Gyrodine and Tiger-Heli, the former of which had been the start of a relationship between these future-Toaplan employees and the successful arcade publisher. Taito, over the next nine years, would serve as publisher and distributor for 13 additional Toaplan games, many of them shoot ‘em ups like Tiger-Heli — including the game’s two sequels, Twin Cobra/Kyukyoku Tiger, and Twin Cobra II/Kyukyoku Tiger II, which Toaplan did not manage to complete prior to their closure in March of 1994. However, ex-Toaplan employees managed to finish the job they’d started, as Takumi, on a Taito arcade board with Taito as publisher, and the game released in 1995.

Despite the similarities and connections, there was one other major factor that separated Tiger-Heli from not just Gyrodine and other Xevious-style scrolling shooters, but all previous shooting games, or STG. And that was bombs. Bombs in a shoot ‘em up are maybe something you never considered the origins of, given their ubiquitous nature in the present, but they, like every other feature and mechanic, had to start somewhere. And Tiger-Heli was that somewhere.

Bombs are used for so many different purposes in shoot ‘em ups. In some games — like basically everything Cave has ever developed — the use of them is frowned upon, and you’re even rewarded for not utilizing your most destruction option. In others, like Compile’s Seirei Senshin Spriggan, the bomb is central to your offense, its use encouraged to the point that you’ll just die a lot if you don’t bother. In something as high-level as Battle Garegga, bombs are one way to control your rank, and failure to deploy them will not just make the moment you’re in more difficult, but future moments, too. What’s a bit surprising about Tiger-Heli is that basically all of this is true, to different degrees, about the bombs in their initial genre appearance. You can’t lower rank in Tiger-Heli, as it just increases over time, but bombs make certain portions of the game manageable for players of pretty much every experience level. You’re awarded points for not using them at the end of a stage, however — 5,000 points each, in a game known for not handing out points — so maybe it’s worth it to you to not rely on them too much.

And what makes their versatility that much more intriguing is that practically none of that was Toaplan’s goal when they introduced bombs to the mix: players figured out their uses, their pros and cons, and developers took that gleaned knowledge and began to iterate on the innovation in their own games. Toaplan’s goal in introducing the bomb was basically, “that rocks.” Not to say that they didn’t have anything else to do with it — they programmed the point rewards for holding onto bombs in the first place, for instance — but it was the players that figured out the strategies for them, with Toaplan’s own employees saying as much. Here’s Uemura on the subject, from that same 2012 interview:

—You mean the bombs weren’t designed to balance the game, that is, to help beginners in a tight spot, or to be saved up for score at the end of a stage?

Uemura: No, we didn’t plan for them to be used as safety measures like that.

—You weren’t concerned with game balance, but you just wanted that feeling of seeing something go BAM and explode?

Uemura: Yeah, that’s what we were enthused about. Our thinking at first was that bombs were to be used aggressively for attack, but in the end skilled players wouldn’t use them. You could say they ended up having a different value than we had conceived. They’d clear the stage without using a bomb for score, or never use bombs for the achievement of it.

—A new interpretation different from your original intentions had been created.

Uemura: You could say that. People started using them only as an emergency, and it became customary to see how far you could get get without bombing.

And Masahiro Yuge, another composer/designer/programmer from Toaplan, in a separate 2012 interview with STG Gameside:

Yuge: We aimed for a kind of game in which, when a player died and wondered what killed him, he would be able to say to himself “Next time I should do this.” In that regard I think we learned a lot from Xevious. In Xevious the speed of the game was designed such that players had to do devise all these plans, like moving their ship to a certain point when the screen had scrolled just so far. Things like that really taught us a lot. But we also thought of ways to get rid of the impatience inherent to the slow pacing of that game. What livened things up for us was when we added bombs, rather than making everything be about precise aimed shots.

—Lately shooting games mostly use the bomb as a way to save the player.

Yuge: Yeah, that’s true. With Tiger Heli and Kyuukyoku Tiger, we wanted the players to use the bombs as aggressive weapons, but the fact that beginners ended up using them to save themselves was a good thing, even if unexpected, I think.

Bombs were meant to be noticeable on the attract screen, to draw the eye of potential players. They were meant to be a show of explosive force that were fun to use. And they did succeed as both of those things, but players took the initial idea and made bombs into their own thing, too, almost immediately changing the meaning and potential utility of them, which in turn influenced developers and game design. What a satisfying little loop that was.

Bombs, like the Little Heli, could absorb a shot for your main craft. The difference here is that the Little Heli would merely crash and be gone: a bomb shot by an enemy is automatically fired and explodes, killing or damaging anything in its blast radius. This, too, is something of a… well, not standard, but not uncommon practice in later STG. And in fact, M2 has incorporated it into the Super Easy mode versions of a number of not just their Toaplan re-releases, but shoot ‘em up re-releases in general.

Like the Little Heli, you could hold just two bombs at a time in Tiger-Heli: bombs in stock were actually visible on your chopper instead of just as item icons on the HUD. One on the left, one on the right, and when used or exploded by foes, the bomb in question would disappear from view. That’s some kind of graphical detail for 1985, and it’s consistent throughout, as you even have the bombs disappear when your chopper lands in between levels and your remaining bombs are cashed in for points before being restocked for the next stage.

There are no weapon changes or power-ups outside of the bombs and Little Heli, which, when combined with the slow pace and movement speed of the chopper, can make Tiger-Heli feel its age sometimes. You fire as fast as you can hammer on the button, and that’s that. However, you also don’t want to just be mindlessly firing, either. You want to keep track of your shots, if your goal is to score as many points as possible and secure the much-needed extends. And that’s because Tiger-Heli’s primary scoring secret comes from secret cars that’ll appear on screen in certain predetermined locations that you have to memorize — and they only appear when you cross an invisible threshold with a multiple of 16 shots fired to that point.

It’s not super apparent on a first play, no, but the signs are there for you to figure it out and for an arcade-based gossiping to make its way to players. An example: there are exactly 16 destructible objects to fire at in between the start of the game and the first secret car that appears, so if you don’t miss and don’t fire extra shots, it shows up, and suddenly you go from a handful of points to having a big chunk of what’s needed for your first extend taken care of. Observe:

This video is from the Toaplan Arcade Garage re-release of Tiger-Heli that M2 put out in 2021, and includes the “Gadgets” of the M2 ShotTriggers series on the sides of the screen. One such default gadget in Tiger-Heli counts your shots, by going from 00 to 15 before looping back around, and it even shows the car lit up and racing underneath when you’re sitting at the double zero. Paired with the map on the right side of the screen that shows where the secret car locations are, and anyone can, in theory, snag those 10,000-point bonuses.

Even knowing where they are and what your current shot count is doesn’t make getting these cars easy, however: that first one is found without much opposition, as is the second, but before long the areas with cars are also loaded with enemies, so you have to chose between survival or scoring, unless you’re exceptional at the game and can manage both. Even if you are great at this, you still might get blown up trying not to shoot an extra time, or accidentally fire one more or even fewer time before the invisible threshold is crossed and your opportunity to trigger the car lost.

The last important item to note, also often hidden, are the diamonds that appear on screen and then disappear just as quickly. Shoot 10 of these and you earn an extend, but in order to ensure that you even get the opportunity to see that in action, you’re likely going to have to find the hidden ones that are often clustered together, just maybe off the path from where you’re traveling and firing. If you hit one of these hidden ones, it appears, so keep firing until you find the others. You’ll need the help.

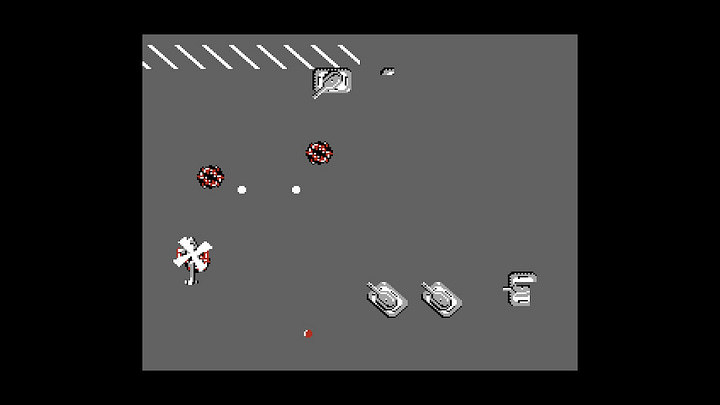

Tiger-Heli is notoriously difficult. Enemies fire on you once their guns are trained on you, and while that takes quite some time early on, the longer you play, the faster their guns swing around to target you, and the more regularly they’ll fire, too.

You saw how the tanks in the first video barely had time to get off a shot before being blown up. The rank difficulty, as shown on the Gadget in that video, is set at “1” at that point, as it’s right at the beginning of the game. By the end of stage 2, that difficulty is set at “15,” and as you can tell by the fact the gauge is still displaying a green light instead of a red one, things haven’t even begun to get ridiculous. And yet:

It’s not just the increase in the number of tanks. They’re firing more often, too. Dodging becomes hell, especially in that slow chopper, but that’s the game. There is no bullet sealing here (for the uninitiated, bullet sealing occurs in many games when you get close enough to an enemy that it stops shooting, so you can hover right on top of or next to some enemies to keep them from firing while you destroy targets that are further away), either, so you can’t even go real close to a tank to keep it from firing at you or to try to blow it up and put a stop to its shots when you’re further away, either. If you get close to a tank in Tiger-Heli, you just took away any time you had to dodge the inevitable shot it’s going to fire at you.

Why is the chopper so slow? It has to do with the strategy behind Tiger-Heli. It’s a game that requires very intentional movement and memorization of paths to take and safer spots to move in. If the helicopter were faster, as Yuge explained, “we’d have to make the bullets faster in order to keep the difficulty balanced, and we wanted to avoid doing that… increasing the ship speed allows the player more freedom of movement, but that would mean that the make the routes the player could plan through each stage would become much more sloppy, and less strategic.” Instead, with an eye on less experienced and new players, the chopper moved slowly, and enemy bullets were clearly visible and able to be avoided. They’d speed up over time, yes, but by that time you’d already developed the idea that you were mastering this game, and another quarter would get you even further, and then another, and so on. Tiger-Heli is very much a memorizer-style shooter that’s about more than just reacting to fast-moving bullet patterns and hoping you pick the correct movement path. You plot out that movement based on experience, you make it into muscle memory, and then, suddenly, you’re posting your personal-best score.

Tiger-Heli has no real boss fights — there are some square for-the-game massive tank-like enemies with multiple turrets you have to contend with, and in very Toaplan fashion, sometimes there are two of them at once — but they aren’t screen-filling combatants, and these bouts even occur in the middle of a stage sometimes. Even without bosses, the game is tough. There are just four stages, and they increase in difficulty basically exponentially due to both the added number of foes on screen and the rank changes, then loop forever starting from stage 2. Looping was seen as a reward for experienced, talented players, a way to get them to continue engaging with a game that they had, at its base, mastered, and was a feature Toaplan became known for implementing in their STG. As Yuge told Gamest in a 1990 interview, “We do that to extend the life of the game for skilled players. Its [sic] said hardcore players spend a long time playing, but they also spend a lot of money on the game to get that good. So it would be unfair and boring for them if the game just ended all of a sudden.” Uemura continued, “You see them and think maybe you could do that, too.”

Tiger-Heli was a hit in the arcades. It released in July of ‘85, and as of October, per the trade paper Game Machine, was the number one table arcade game ahead of titles like Ghosts ‘n Goblins and Gradius. It would receive a port to the Famicom in Japan and the NES overseas, with Pony Canyon handling the former and Acclaim the latter. The port is severely lacking in a few ways, which shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone familiar with the work of developer Micronics in the 80s, but it was also a real success at home, too. The port sold 1 million copies, making it one of just 78 titles out of nearly 1,400 officially licensed ones to manage that feat on the system: 1 million sales put Tiger-Heli right behind hits Mega Man 3, Adventure Island, 1942, Bomberman, Gradius, Metal Gear, and Hydlide. Toaplan had nothing to do with the port, or any port of their games, for some time: their focus was entirely on the arcade, and the only reason the Mega Drive/Genesis ports began to be made in-house was due to similarities in the hardware.

So, Tiger-Heli was a huge hit, but one without Toaplan’s name on it. And the NES port was also a hit despite its inferior quality, but Toaplan had nothing to do with it. It’s maybe not difficult to see how this developer ended up being so vital and influential while also remaining comparatively unknown to some of their peers. Tiger-Heli was the start of something for the company in more ways than one.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

Never played that but I loved Desert Strike which I'm guessing was the next generation.