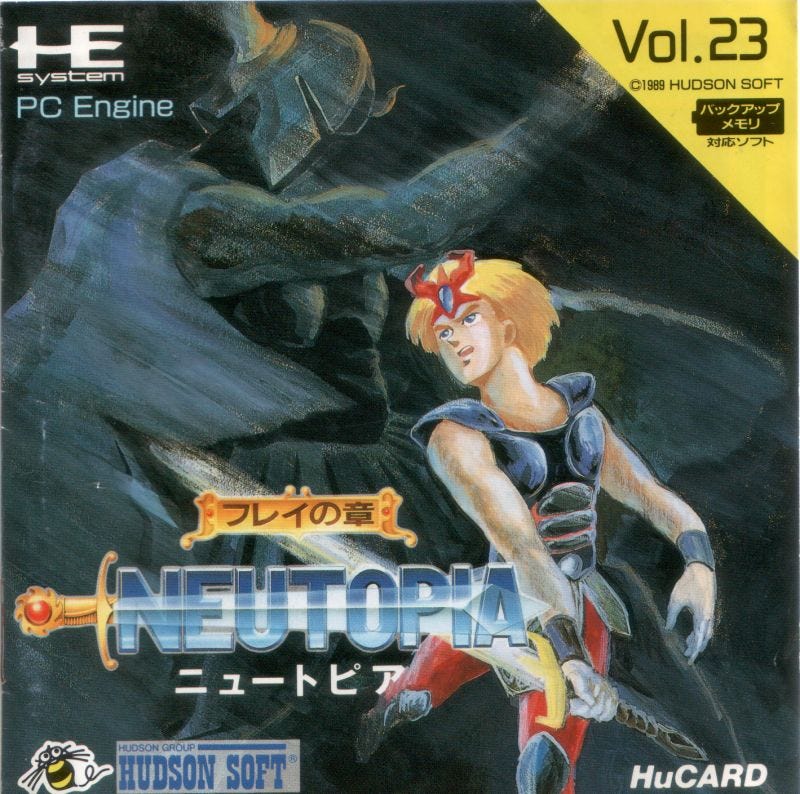

Retro spotlight: Neutopia

The kind of game "Zelda clone" was invented for, but the term also doesn't have to be a negative.

This column is “Retro spotlight,” which exists mostly so I can write about whatever game I feel like even if it doesn’t fit into one of the other topics you find in this newsletter. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

If you’ve been reading this space for some time, you know how I feel about the term “Zelda clone.” It was thrown around far too liberally and quickly in the 80s and 90s as both an accurate descriptor to let you know what you were in for, as well as a pejorative. As I wrote while featuring Crusader of Centy back in 2021, it was all a problem with language:

Adventure is the real progenitor of it all — released in 1980, the Atari, well, adventure, literally changed the game, but it would take the post-crash popularity of the Famicom/NES and the introduction of Zelda to ensure this was a genre that would grow and grow and be endlessly riffed on by other developers and publishers. Zelda is an adventure game, but because it ended up so popular, and because other developers and publishers and console manufacturers wanted their own Zelda, we didn’t get more “adventure” games. We got Zelda clones.

It’s a problem with language. Platform games were already well established by the time of Super Mario Bros., so every platformer that released afterward was not known as a “Mario clone,” not that you didn’t ever hear that sort of thing. Every genre has its starting point: platform games were often referred to, in their early days, as being in the style of 1981 arcade hit Donkey Kong. As that genre kept on churning out new games, new advancements, and so on, it eventually was widely accepted that they were platformers. “Zelda clones” would similarly start to just be called adventure or action-adventure games, but there was a good period of at least a decade where if it looked or played even a little bit like Zelda, it was a clone, with the implication being, fairly or unfairly, that it was inferior to the real thing.

Many “Zelda clones” were called such for the same reason that every first-person shooter on the market was referred to as a “DOOM clone” for a while: there just wasn’t a word for what those were yet, and so, “hey, it’s kind of in the same vein as [extremely popular and well-received game you know the person would understand the reference to]” ended up with the same descriptor as “shameless ripoff.”

Time and familiarity often fixes these issues — we now know games in the style of Zelda as “action-adventure” titles, a genre broad enough to encompass both the original clones, the advances and changes in Zelda games, as well as more modern outings like the combat-heavy Darksiders, while first-person shooters are one of the most lucrative and repeated genres out there with its own subgenres, one of which is “boomer shooters,” or, first-person shooters that recall the style of DOOM. And sometimes time does nothing but entrench the original term: I wish we had another widely accepted and understood word for Metroidvania besides that one — pathfinder, what’s wrong with pathfinder? Listen to Brendan Hesse — but we do not.

This brings us to Neutopia, which is basically the kind of game that “Zelda clone” was invented for. It’s not a ripoff nor a cash grab, but it’s also not subtle at all about its inspirations, and the goal of it was clearly to have a Zelda-style game on the PC Engine and Turbografx-16, to show that hey, Hudson and NEC’s machine could have the kind of games you were buying a Famicom/NES for, too! It doesn’t differentiate itself from its inspiration nearly as much as console-specific platformers would from Mario, but as quoted above, that’s in large part because platformers were already an established thing in the days before Mario: Zelda was not just the peak of its genre, but also in many ways was the genre, too.

Time has dimmed some of Neutopia’s shine, as Zelda games evolved well beyond the original and even circled back to their roots to make one of the finest games ever just a few years back. Since Neutopia — which also starred a young man (Jazeta) going off on a quest to rescue a princess and recover eight missing McGuffins — didn’t have quite the lofty heights of The Legend of Zelda, it didn’t have as much room to fall before it was no longer as impressive as it was at launch, but none of this means it’s not any good, or never was: Neutopia is still a good game, but that’s all. It refined some aspects of the Zelda experience, gave the genre a major leap forward visually in the two years before A Link to the Past would land on the Super Famicom in Japan, but also fell short in a few notable ways that helped Zelda win the war, as it were.

The good: Neutopia, being on the much more powerful and visually impressive Turbografx-16, is a real step up on the graphical side from The Legend of Zelda. Whereas The Legend of Zelda had you heading into caves that were just a border with solid black, with a clearly 8-bit sprite in the middle speaking to you with white text on that blackness, Neutopia features full-on rooms with tiles, walls, and little touches like pools of water, lighting, and so on. The sprites of the various people you encounter, be they townsfolk or villagers or sages or whatever, look detailed enough that there’s more similarity between how they appear and how A Link to the Past’s villagers and character sprites would end up looking than anything from that game’s actual predecessors.

It’s not just the extra horsepower that was put to good use, however, as NEC did an excellent job of localizing the work of Hudson Soft from Japanese into English: there are no accidental riddles to solve, nothing that would inevitably become a meme for how weirdly it was phrased, no characters accidentally telling you completely incorrect information due to poor localization work. It’s been easy to forget over the years, since Nintendo has cleaned up The Legend of Zelda’s most egregious localization errors for re-releases over the years, but the original was a mess — enough so that it was the first subject in Clyde Mandelin’s “Legends of Localization” series of books. (Highly recommended, by the way, as Mandelin discusses not just the localization of the game’s and manual’s text, but also how Nintendo handled the different sound capabilities of the Famicom Disk System vs. the NES.)

The Fire Wand existed in Neutopia before the Fire Rod appeared in A Link to the Past, and honestly, Neutopia’s is the better item because of how it’s utilized. Unlike with A Link to the Past’s iteration of it, the Fire Wand can shoot endlessly instead of being tied to a limited pool of magic power, but that’s not the key difference. No, it’s that the strength of the Fire Wand’s shots, as well as the shape of them, is impacted by your character’s health. At full strength, a burning wave of fire is shot out that will set anything in its path aflame. At levels of lower health, a ball of fire with varying range and strength is shot out of the wand. It’s not as strong as your higher-level swords, but it does act as your ranged attack, and fires diagonally, too, a role that the boomerang ended up playing in A Link to the Past — the only real difference there is that the boomerang can retrieve items, too.

It’s not just the visuals, but also the audio, that Neutopia separates itself from The Legend of Zelda. It’s often much faster-paced, and pulls, stylistically, more from the kind of action RPGs that would appear on Hudson and NEC’s system, such as Ys. Which is not to say it sounds just like Ys or anything, but it’s clear that composer Tomotsune Maeno was thinking more about that kind of sound than anything Koji Kondo came up with a few years prior.

It’s admittedly a bit reductive, but a shorthand that’s accurate more often than you might think is to assume that composers working on 80s and 90s JRPGs (turn-based, action, or otherwise) and action-adventure games like Zelda and Neutopia were influenced by either hard rock and progressive rock, a la Yuzo Koshiro, or by Joe Hisaishi. Koji Kondo has proven time and time again with his work on Zelda games that he and Hisaishi share plenty of similar tastes, and on the other side, Maeno clearly thought Koshiro was on the right track with the emphasis on music that compels you forward. And hey, nothing says you can’t be plenty influenced by both. Just ask Nobuo Uematsu.

The only complaint you can really make about Neutopia’s soundtrack is that the tracks are all fairly short, in regards to how long it takes them to loop around again, and there just aren’t a whole lot of them, either. Then again, it is a real short game, so don’t take modern action-adventure completion times into account when you think about how the above soundtrack video is just over 10 minutes long, or how a gamerip of the OST’s 20 tracks that also includes some sound effects totals 24 minutes.

Neutopia is fairly open, but not to the degree of The Legend of Zelda: you have four different “spheres” to travel through, each corresponding to a different kind of land to traverse (like land vs. sea, a subterranean world), and each sphere has two dungeons within it to explore. The dungeons don’t have keys, so you’re free to go wherever in them at first so long as you can solve the puzzles that lock the doors, which makes for a different gameplay experience than The Legend of Zelda, and the bosses are much different as well. Not just visually — they’re a massive step up both in terms of sprites and design from what The Legend of Zelda managed on that side of things with its bosses — but they’re also more involved affairs, with the need for pattern recognition and reactions, plans of attack you need to come up with on the fly, and so on. Why have two flying foes in a boss fight coming at you from different angles when you can have that but also make them throw knives in a circular spread pattern at different intervals, too?

Those puzzles, though… that’s where some of the bad about Neutopia comes in. They’re overly simplistic, and also numerous. Push a block to solve the puzzle. Alright, now push a block for this puzzle. And this one! The kinds of puzzles you’re presented with aren’t varied enough, and they’re also a constant, since there aren’t any keys. In addition, the general lack of items you receive in the game means fewer ways to solve things, which feeds into the lack of change from puzzle to puzzle. You can throw more and more enemies in, and different ones, in “puzzles” where the solution is killing everything in sight, but over eight dungeons across four spheres, you’re going to want some more variety than that. Neutopia doesn’t have it.

The items that are in the game are certainly nifty — the Fire Wand was already covered, but there are also wings that, when used, warp you back to the last save point/password room you were in, a book that will also bring you back to a checkpoint when you die albeit with half the money you were holding, and magic rings that transforms enemies into weaker foes, making them easier to defeat. There just aren’t many of these kinds of (for the time) forward-thinking items, and some of what’s here is used for the same kinds of things they were, in a different form, used for in The Legend of Zelda. (As for those save points and password rooms: if you were playing on the Turbografx-16, you needed to use lengthy passwords to resume your game, but if you were using a later model with CD-ROM capabilities, there were some built-in slots for saving to utilize instead, which saved you time and erased the sting of again, lengthy passwords to have to write down and then input.)

I do like the compass, though, which helps direct you toward the next dungeon you need to go to — again, this isn’t a big open experience, but a little more linear and pushing you toward the next thing, which also makes it more like future Zelda titles than The Legend of Zelda. The compass does not lead you to whatever it is you need to do, defeat, see, reach, whatever in order to actually open the door of that next dungeon, no, but it does get you there. So you’ve got a balance of “hey, go this way” with “hey, I’m just a compass” going, at least.

Neutopia certainly influenced some of what would come in the genre, as it wasn’t just a repeat of what existed in the genre — it wasn’t a shameless ripoff or literally the same game again, only worse, even if it’s pretty clear where the inspiration came from — but the total package was still missing something to bring it to that next level. Nintendo had plenty of momentum on their side for a number of reasons, but Neutopia, for as fun as it was and can still be, wasn’t going to be enough to knock them or Zelda from its perch. A Link to the Past might have been surpassed time and time again by Zelda titles that followed it, but in comparison to Neutopia? Well, there is no comparison, not really: one is considered an all-timer, and the other is the subject of a story that talks about how “Zelda clone” is probably used more harshly than it should be too often.

That being said, if you’re into the very old-school style of The Legend of Zelda and want to see into the brief past in between that game and what the series would eventually become, Neutopia will show it to you. It’s enjoyable, albeit simple in a number of ways, and is still available on Nintendo’s Wii U eShop for two more months, as well as on the Turbografx-16 Mini, and buried on the Playstation 3’s version of the Playstation Store. Your options are pretty limited, but it’s worth the look if you enjoy this particular brand of action-adventure.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.

Great piece. Also a reminder to why I support emulators and Everdrives. I wish this game was easier to get.

Great read! I think I have both games on Wii. No save states there unfortunately. Are these games where save states provide an enormous QoL improvement? I ask because I'm thinking of getting them on Wii U. And not to spoil a possible future article, but is Neutopia II worthwhile?