Retro spotlight: Yakuza

The original Playstation 2 version of Yakuza remains fun, but it's the idiosyncratic bits that stand out 18 years later.

This column is “Retro spotlight,” which exists mostly so I can write about whatever game I feel like even if it doesn’t fit into one of the other topics you find in this newsletter. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

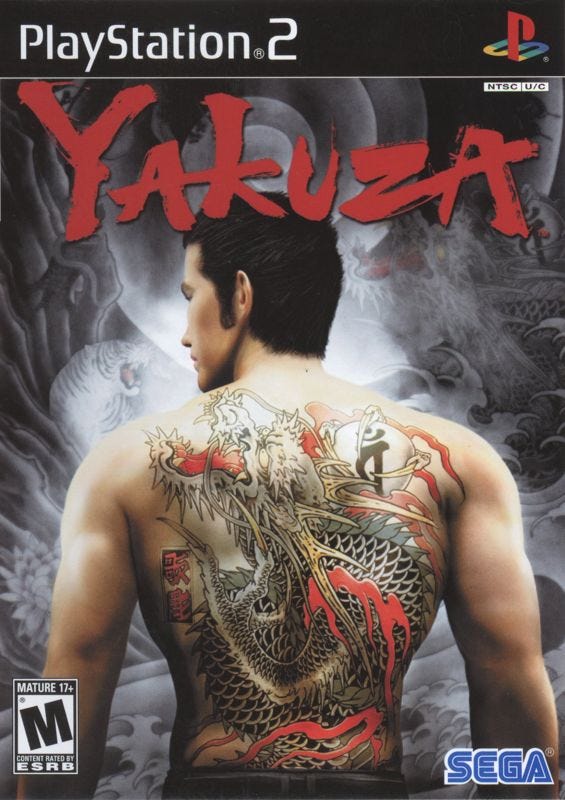

Localization is the story of Yakuza, first released for the Playstation 2 in North America in 2006. The Japanese edition had come out the year prior, where it was known as Like a Dragon. It was a Japan-centric game, taking place in a made-up but realistic district of Tokyo known as Kamurocho, and so there was very little need for such a game to be designed in a certain way to be understood or appealing to the audience it was intended for.

For North America, though, there was still a belief that games needed to be marketed differently, that something that was considered Too Japanese might not sell as well as something that had been Americanized a bit. Hard to imagine why that would be, if you didn’t live through the era of very popular outlets being very racist about role-playing games made in Japan, but trust someone who was there about why a Japanese publisher might have some reticence about that for a game they think could be a big hit overseas.

Localization is important! It’s contextualizing a piece of media for audiences outside of the original one, and the work is vital, no matter how many people think a 1:1 translation is the only correct way to handle things. So, Like a Dragon underwent some radical changes. Changes that could have worked if handled correctly, but that’s the rub. Like a Dragon became “Yakuza” even though the protagonist, Kazuma Kiryu, is an actual member of the Yakuza for about 20 minutes 10 years before the actual setting of the game kicks in, and this was merely the start of the changes.

Changing the name wasn’t really a bad thing — Yakuza does jump off the box a bit more in North America where it’s not simply the equivalent of naming a game “Mafia” (no offense intended to the actual series of games known simply as Mafia), and the story does still revolve around yakuza even if Kiryu isn’t one for 99 percent of the game’s runtime. But it also serves as an introduction to why Sega’s localization team bothered to do what they did here. The idea was to make the game seem more violent, more criminal, and edgier than it actually is. Yakuza was a highly ambitious game that kicked off a series that remains that way nearly two decades later. But it was not originally meant to be a “Japanese Grand Theft Auto,” even if that’s what it was marketed as out west to bring attention to it.

It has criminals! It has violence! It’s got some open-world elements! Obviously, this is Grand Theft Auto in Japan. Not really, no, as it was designed to be far more cinematic, for one, and you weren’t committing violent acts against innocents because you felt like it. Yakuza wasn’t a sandbox where you could do whatever you wanted. It had some highly specific structures and rules in place, and chaos wasn’t the point. If anything, you as Kiryu were meant to sift through the chaos that others were causing. But this is the direction the marketing took, because, well, Grand Theft Auto III sold 14.5 million copies, Vice City 17.5 million, and San Andreas 21.5 million. “Hey kids, want to play our criminal underworld video game?” is an understandable tactic when you see those numbers scrolling past.

Luckily, Sega didn’t go so far in their Americanization efforts to change, say, the food that Kiryu could buy, like Konami had done with The Legend of the Mystical Ninja a decade prior. Convenience stores didn’t swap out their bento boxes for hot dogs, ramen shops weren’t replaced with pizza places. The game remained as Japanese as it had always been in these respects, but that only served to make the parts that did change to be more clearly Americanized that much stranger. If you’ve never experienced a heavy New York gangster accent coming out of the mouth of a yakuza member, well, then you’ve never played the original version of Yakuza. How else would audiences be able to understand that yakuza were gangsters? There was simply no other way to achieve this goal.

Listen, John DiMaggio is incredible at what he does. The man has voiced a ton of iconic characters, and even when he’s in an “additional voices” role he’s always delivering. Having him doing his usual John DiMaggio voices for yakuza characters, however, is just… jarring. Nothing you hear quite matches the tone of what’s actually happening or displayed on-screen, and it doesn’t help that the script of the localization is, itself, awful. It would have been noticeably an issue even without knowing how every Yakuza game after this one was going to sound in terms of tone and characterization, but armed with that knowledge, it’s a nightmare.

There are so many swears. Just like, every other word. As someone who swore like a sailor before having kids made him have to keep that in check, I’m certainly not offended by the presence of swearing — hell, I tell those same children that the reason they shouldn’t swear at school is because it’ll be inconvenient for me when I get a phone call about it — but this is cursing at distracting levels. And not just when someone delivers the strangest pronunciation and cadence of “motherfucker” that you’ve ever heard in your life:

Are you telling me that was the best take they had to use? The one where he started buffering in the middle of the word? Were they desperate to sync up the word “motherfucker” to the way the character model’s mouth was moving so they just completely butchered the saying of it? I’m fascinated by this decision, whatever it was.

Seriously, though, Yakuza’s dub is absolutely loaded with swears. Kiryu comes off looking strange and mischaracterized if you have any knowledge of what he’s like in later games, and it’s not because this was the first game in the series and he just hadn’t been established yet. It’s the localization that turned him into kind of an edgy dick who just happens to be less problematic than the dudes he’s fighting — Kiryu in the remake, Yakuza Kiwami, is the same Kiryu that was in Like a Dragon, and he comes off much better, much more complete, much more relatable and understandable. The localized version of the game is a strange artifact for many reasons, and the way it handles Kiryu — even having him drop an r-slur during the game! — is completely out of step with what he was supposed to be. But the idea was to appeal to the GTA crowd, so, North American got an edgier, swear-happy Kiryu who was less concerned with honor and what was right than he was about getting to kick some asses and joking while he did it.

The real issue, though, is that the voice direction is just way off. There’s some serious talent in the Yakuza dub! DiMaggio already got a mention, but Mark Hamill is here, as well, playing Goro Majima. Which, really, that’s perfect casting for an English-speaking audience, especially this particular version of Majima that’s as violent and unpredictable as he is. Even Hamill can’t quite nail the performance, though, as it’s just as off as pretty much the rest of it. Combine a poor localization with poor voice direction that resulted in some baffling line deliveries and tone that’s both inconsistent and at times incomprehensible, and it doesn’t really matter that you’ve got legends like DiMaggio and Hamill on board, that you brought in Michael Madsen and Eliza Dushku and Rachel Leigh Cook and literally Bill Farmer for the cast. This is a pure garbage in, garbage out scenario, even when you’ve got the best trying to make it otherwise.

That all being said, the dub is actually bad enough in the “right” ways to come back around to being entertaining. It’s not good, don’t confuse it for that, but it’s got its charms thanks to its idiosyncrasy, and is worth experiencing if you’re used to Yakuza games in the era where Sega did a far better job of localizing — when Sega realized that changing the entire vibe of the game’s script was the wrong way to prepare it for western audiences. It was a trip, but I could also see how this particular job, back in 2006, didn’t do Yakuza any favors and maybe even kept it from being a bigger deal, and why Sega just decided to go with subtitles only for a decade after this one rather than use English-speaking voice actors for a dub again.

As for the game itself, Yakuza holds up surprisingly well despite the leaps in hardware and ambition in the series since then. That wasn’t guaranteed, considering that one of the weaker Yakuza games in the entire series is the Kiwami remake built with the engine and ethos of more modern (and far more popular) Yakuza games. The performance of pretty much everything is worse, as it’s very much a late-life Playstation 2 game impatiently awaiting the Playstation 3. The ambition to do so much more is there, but the hardware can only handle so much, meaning, there are constant loading screens or at least loading hitches when you move from area to area, when you engage in a battle, when a battle ends, before cutscenes, after cutscenes… it’s a lot of loading. The camera is also a bit of a mess, since it follows Kiryu from a distance but isn’t very zoomed out, since each little block of street is its own section that has to be loaded up before you move into the next one — hence the little stutters and hitches. It’s like playing a Xenosaga or a Resident Evil from before RE4 in that respect — not a bad thing, just very much of the time, where you know exactly when the disc is actively doing something and when it’s finished until the next thing to load pops up.

Much of the game will be spent fighting in brawls, but there’s a heavy emphasis on story and cinematics, too, and you’ll have plenty of time to explore. The story itself — Kiryu nobly takes the fall for a murder for his lifelong friend and fellow orphan in order to allow him to live the life Kiryu believes he deserves, only for the yakuza and his buddy to devolve into the worst versions of themselves while Kiryu serves time, creating mysteries and messes he must clean up once he’s free — remains a great one. Fewer twists and turns and less expansive than in later Yakuza games, yes, but its greatest fault remains that other Yakuza games exist, which is not a knock against it so much as a compliment to the others.

Yakuza is very obvious about when you’re going to cut yourself off and head to the next chapter or the event that precipitates that moment, often leaving you a character to speak with who will give you the choice of going or finishing up some things first. This is your chance to walk around the district and complete the substories that populate every Yakuza game, to get to know the characters you’ll interact with in ways other than just fighting, and the city that they call home. These aren’t as clearly or obviously marked here in the original Yakuza as they’d eventually be, but you can still find them by walking around and looking for the people who are ready to have a conversation, then go from there. They add a depth to the game that makes it more than “just” some brawls in between cutscenes, and it’s welcome even in this early form.

Fights aren’t quite as smooth as they’d get in the future, but they’re also simple enough to not be bogged down by some of the annoying qualities that would occasionally hamper later Yakuza games before being changed up for sequels. Everything is based off of some simple combo work, based on pressing the X button for some light attacks before moving into heavier ones with the triangle button, or holding to charge up, or grabbing a foe to start wailing on them that way. You still charge up your Heat meter so you can perform some painful special attacks using the triangle button, and you can still lift a bike over your head and smash your enemies with it while giggling. It’s Yakuza! It might feel kind of proto or nascent in some ways, but it’s very much already Yakuza in a way that’s very plain to see.

You can still equip an assortment of weapons and armors to boost your stats, you can still chug Tauriner to charge up your heat and recover some health, or take a little menu-based break to inhale a bento box in the middle of a fight so you have a better chance of surviving. Really, other than the completely absurd rate of swears and the horrible voice direction, there’s very little to complain about, as Sega already knew what they had here, at least as far as the core game goes, and simply refined it all and made it bigger from this point forward.

You gain levels by earning experience — through fights, missions, and eating meals in restaurants to recover health — which you then put into one of three different places. One focused on your Heat meter, one on your Techniques, and one on your Health. You learn more powerful and impactful ways of escaping the clutches of a foe through these upgrades, new ways to extend combos or end them with a much weightier exclamation point of an attack, and extend the length of both your Heat and Health meters this way, as well. It’s all your choice, which you level up and when, but know that it’s difficult to focus too much in one space due to how quickly the experience cost of each goes up after leveling. Yakuza isn’t particularly difficult to get through if you pay attention to your levels and make sure you equip some gear while keeping your items stocked. It’s considerably easier than Yakuza Kiwami, really — that, or playing every single Yakuza game and then going back to the true beginning has just made it so the expectations of the original are easier to overcome than they would have been if I had started here. It feels different, at least, since you don’t have to worry about matching stances to your opponents’ strengths and weaknesses, and have to focus more on crowd control, on making sure you’re blocking when you need to or properly strafing in a one-on-one situation, and all while hitting enemies over the head with a couch when necessary, too.

What the “it’s a Japanese Grand Theft Auto!” marketing and analysis missed out on was that Yakuza was very much a translation of the beat ‘em up into three dimensions. God Hand was another such game that made this effort, though, the two handled the task in markedly different ways. Yakuza took some core tenets of the beat ‘em up — fights on the street and in alleys and in buildings against semi-anonymous foes with health bars, the ability to pick up a variety of items to use as weapons, and the player’s need to reckon with always being outnumbered and how to best and most efficiently survive that issue — and applied it all to an action-adventure experience. Yakuza is a beat ‘em up, but one that has plenty in common with a Zelda or an action RPG, too, without quite being any of those things. In the end, it’s something new: it’s Yakuza. God Hand, meanwhile, was very much converting a historically 2D genre — the belt-scrolling beat ‘em up — into 3D, in the same way that Super Mario 64 made the jump for platforms, and Ocarina of Time for action-adventure titles. It’s an easier to understand affair, in that regard, or at least it should have been, but it was misunderstood to the point of having some legendarily bad reviews and review scores of it, and its developer, Clover, would close and later independently reform as Platinum.

Curiously, both Yakuza and God Hand, despite their modest beginnings, ended up being an important part of the foundation of Japan-developed video games going forward, alongside the work FromSoftware put out. They’re some of the answers to that sometimes concern-trolling question of “how will Japanese developers survive the switch to expensive HD development?” that used to be asked 15 years ago. It took time for all of that to become obvious, though, which was partly on Yakuza and God Hand, sure, but audiences simply not being ready for what was on offer here plays an even more significant role.

Times have changed, though. Western audiences are ready for Yakuza games, to the point that the series really took off when the turn-based, slower-paced role-playing game versions of them started to come out. The balance these titles achieve with both being expansive, deep games and personal, tightly paced ones is something more developers should strive to emulate. God Hand still doesn’t have the respect it deserves, no, but that game itself and the ethos that created it was the foundation for plenty of future Platinum titles: those games themselves are popular, but more importantly for what’s being said here, they’re also aped by other developers. Going back to the titles that kicked all of this off shows you that, yes, refinements and improvements came, but there was more than just a seed planted here.

The original Yakuza, even with its so-bad-it’s-acceptable dub and localization, is still fun. It’s tightly paced, it doesn’t overstay its welcome, and it introduces you to the district of Kamurocho, which is a well-known character unto itself at this point. There are reasons to go back this far in time, if only to see both how far the series has come and how far it didn’t actually have to go.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.