The Legend of the Legend of Mana

A guest feature on the Legend of Mana, guides, and the "right" way to play a 25-year-old oddity.

This is a guest feature by Patrick Dubuque, who I’ve worked with in the past at Baseball Prospectus, where we wrote and edited a series of features on baseball video games in 2022 and 2023 entitled “Make-Up Games”. Patrick also plays non-baseball video games, however, and had thoughts about the very not-baseball Legend of Mana to share. — Marc Normandin

The Mana series of video games has always thrived on the periphery. Its first volume, retitled as Final Fantasy Adventure in the west, brought a sense of scale to a monochromatic system teeming with single-screen puzzle games. In Adventure it was possible to get lost, in a good way. The second volume carried that immensity to the Super Nintendo in the form of Secret of Mana, the game that instills the vast majority of the series’ nostalgia. Secret had its quirks, and its outright flaws, but its cannon-travel world, its grand soundtrack, and its fantasy opera scale made for a world that felt alive, beyond the semi-linear path of its hero. And the third Mana game, Seiken Densetsu 3 — much later rebranded as Trials of Mana — dwelt even farther in the distance. In the early years of the internet, westerners saw fuzzy screenshots of a game that would take nearly a quarter of a century to legally reach their shores. Under these auspices, the game took on the faint edges of myth, and the series has been trading on that grandeur, despite perpetual mixed reviews, ever since.

Though Secret of Mana holds a place in the hearts of a generation of gamers, it’s a difficult game to go back to, for multiple reasons. Square Enix remastered the game in 2018 for its 25th anniversary, updating it with 3D graphics, cut scenes, and (sigh) voice acting. But as Jeremy Parish noted in his review for Polygon, the switch to polygonal graphics — just as folks were growing to re-appreciate fine sprite work, which the original excelled at — ripped the sense of tangibility out of the game, giving it a sense of weightlessness, characters floating in front of backgrounds. Critics largely suggested returning to the original version, though that provides its own perils; famously retooled halfway through development from CD into a cartridge format, Secret of Mana offers bugs, brutal pathfinding, the standard translation of the era, and a series of (in what would be a hallmark for the series) outdated and often bizarre mechanical choices. It’s a title better off remembered than played.

Mana lives on, improbably, receiving its first mainline entry in nearly two decades with the critically accepted, if not beloved, 2024 Visions of Mana. Between games four (a disaster buried by time) and five, the series existed primarily as a dumping ground of ideas and mobile-gaming opportunism, floating by on its trademark. But in between the legend of Mana and its role near the bottom of Square Enix’s modern portfolio, there was another legend — a spinoff that Americans didn’t realize was a spinoff — the 1999 PlayStation title, Legend of Mana. If its predecessor is best left trapped in memory, Legend can’t exist any other way.

For many, the walkthrough is a dirty word in video game culture. Game designers loathe them for spoiling the intricate work of puzzle design, except when they rely on them to boost profits by engineering puzzles or stashing secrets that would be impossible to solve otherwise. Players tend to consider them a form of cheating, and feel guilty when they go ahead and consult them regardless. Seeing their rise in the early history of the internet, walkthroughs for classic games often feature painfully dated writing, as well as a Dickensian tendency toward verbosity (the bigger FAQ, after all, must have the most facts).

Games have always been experienced in two different modes: as a player, directly inputting the commands, and as a spectator, from younger siblings waiting their turn on the couch to today’s streaming culture. Walkthroughs, however, create a space uncomfortably between the two. The player still has to play, but their inputs are no longer really their own; instead they’re making them under varying levels of command. Playing via walkthrough is more like strolling behind a Virgil — though some Virgils are more eloquent than others — or, perhaps more fittingly, taking a river cruise vacation rather than exploring, or reading about the destination at home.

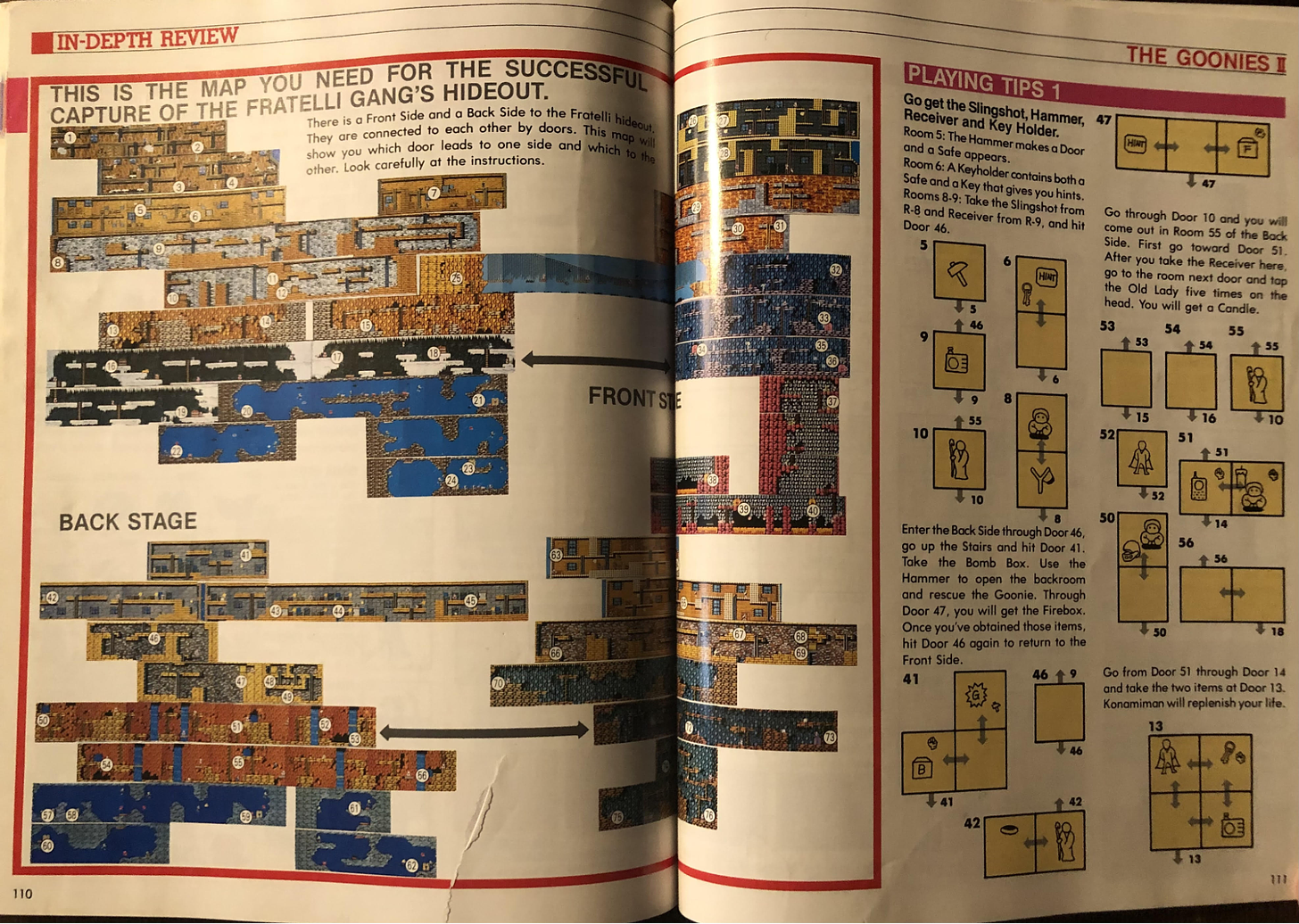

Memory does a funny thing, though: when it starts wiping the slate, it tends to erase the details and leave the feeling behind. The screen with the game lives on and the second screen with the text file vanishes; in the end, when the inputs are made correctly, it’s as if you did it yourself. Sepia-coated reminiscing about the good old days of pre-internet, pre-solution gaming edits out two important factors: the sheer amount of time wasted wandering, pixel-hunting, resetting, reruns of Rescue Rangers droning away in the background; and the internalized screenshots of Nintendo Power, magazines and schoolyard tips and older siblings mocking you for making a wrong turn or using a wrong weapon. Games have always had guides. The place where there was one set of footprints is where The Official Nintendo Player’s Guide was carrying you.

Walkthroughs do, for better or worse, add a layer of separation between player and game, sometimes acting as task listification and other times translation for what’s happening on the other screen. They change how people play, in ways that often interfere with the art itself; so, of course, does checking imdb trivia for a show on one’s phone during a slow scene. The question becomes whether walkthroughs are, necessarily, cheating — not necessarily from the standpoint of succeeding at the game, but cheating like not brushing your teeth before bed, cheating yourself.

Or, as is the case with Legend of Mana, they make the game possible.

Legend of Mana starts off innocently enough. After the title card, you choose between two protagonists, select a starting weapon, and pick a name, all pretty standard, low-stakes stuff. Then it asks you to select a play area within a grid of terrain. “Darkened areas cannot be chosen.” You’re given no other information, not even in the manual. Your choice here does matter — your placement of zones is restricted by land and water, and zones affect each other in ways the game has no interest in explaining — but you’re not going to know how for 20 hours, if ever.

Pretend that didn’t happen, and Legend puts its best foot forward. Start the game and you’re treated to the vibrant, rich colors of the opening cutscene, along with the equally vibrant (and extremely Swedish) title theme by Yoko Shimamura. It’s as good as six minutes get without actually playing a video game. Then, the text begins.

The text dump at the beginning of Legend of Mana feels like a potential leftover from when the game was imagined as a true sequel; nowhere else in the game, until the ending, is this verbose. Fade to black, and the game drops the pretense: You wake up in your cluttered bedroom, a silent potted cactus your only companion. When you exit to the world map, it’s empty, save for your house and an artifact, some colorblocks, that you can place anywhere to create a new location, the town of Domina. From there, it’s up to you.

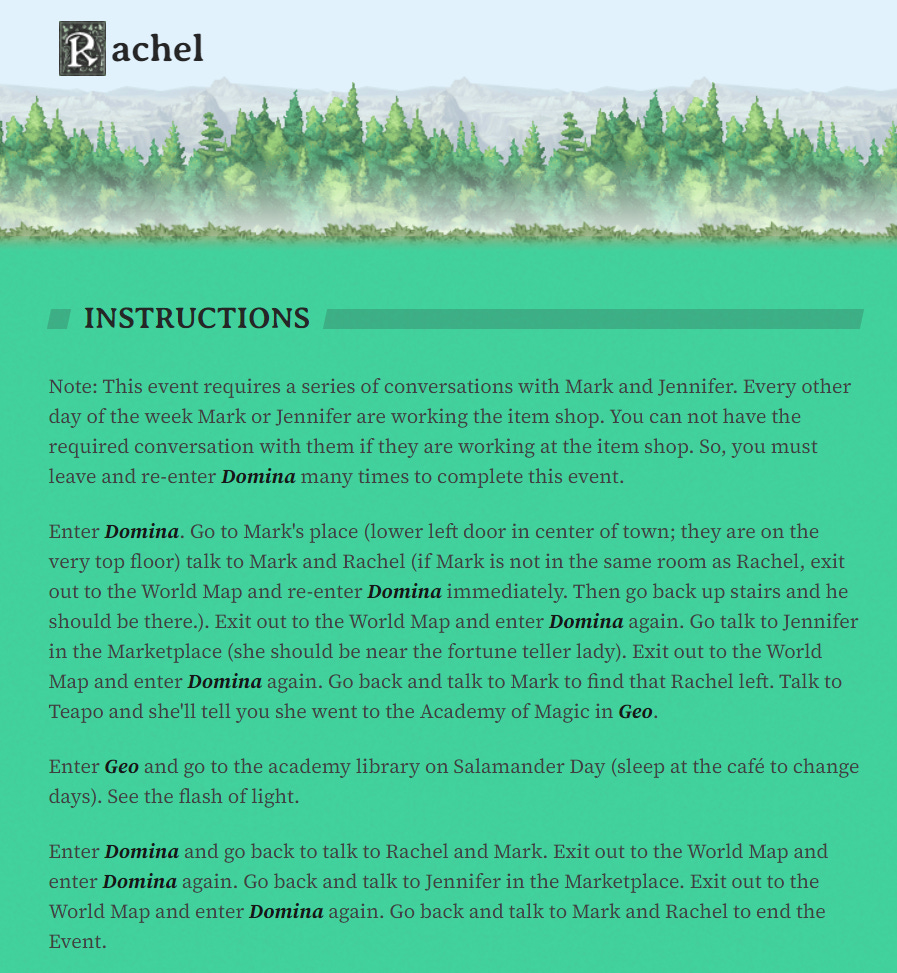

You’re given no linear quest, no directive to save the world. In fact, no one quest in the entire game is mandatory; there are three separate storylines revolving around separate characters, and it’s only necessary to see one to the end to unlock the final stage. Many of the quests begin in a zone you’ve planted but may continue in another place that doesn’t exist yet; your friend in question will disappear, leaving you to wonder if you’re not supposed to be here yet, or if they’re just one screen over and you missed them. Worse still, quest flagging in Legend is as finicky as you’ll ever find. Take this example from the thoughtfully curated Legend of Mana Fansite:

The Rachel sidequest is a perfect example of Legend of Mana, in all its brilliance and failure. It requires zero combat, just conversations with various people in various zones on various days of the calendar. It requires exiting and re-entering zones to change the date, as well as staying at the inn a dozen times, with no indication that the player is at the right location on the wrong day, or vice versa. It demands roughly 20 minutes of the player’s time, most of it spent traversing or loading, with no material payoff. It also contains a touching little vignette of a man who out of pride upsets his wife and alienates the daughter he loves but does not know, told in less than a thousand words.

Reviewers hated Legend of Mana’s story structure in 1999, which was loose to the point of hanging off the bone. Few of the stories tie together, and fewer tie to the mandatorily silent protagonist who isn’t saving the world, or even really solving people’s little problems like a Dragon Quest game. The game strains to hold the player at arm’s length, resisting any impulse to be understood: mechanically, or narratively. It hands you workshops to build weapons and armor, pets and golems, musical instruments, and explains next to nothing about them. It kills off characters and forgets about others for tens of hours. Things just happen. Then it’s over. It always feels like the player is missing something.

There’s a real nobility in this concept, a forceful stripping of both player and character agency. Yes, you do save the world in the end — though from what, or how, or why, slides off the brain in a whirl of pretty music and colors — but you’re barely a part of it, even as you interact with it. You’re given choices but the results, let alone the incentives, are so opaque that there’s no empowerment to those choices, just guessing. The game is designed to make you miss most of it, to feel like there was so much more. That, after all, is what Mana games have always been best at: painting characters and worlds you can’t quite make out.

This is what the game wants. The question is whether you’re willing to provide it. Thus, the walkthrough.

The trouble with remasters is that they are made for adults, out of games that were made for children. No matter how faithful, no matter how expertly crafted and modernized, a remaster can never be both itself at heart and also bond to an audience that has itself fundamentally changed.

Legend of Mana wants you to stumble across the Rachel side quest slowly. It begins in Domina, that first zone you place in the game; its characters (assuming you picked the right day to talk to them) live in a house in the first screen. You’re meant to meet Mark and Jennifer and Rachel, file away their conflict, then return after the placement of the Geo zone halfway through the game to delve into their lives. You almost certainly won’t, because you’d never think to go visit them again without a walkthrough, or without a lifetime to spend in a video game world, i.e. being a child.

Hidden content is, to me, the single most attractive artistic element of video games, something other art forms struggle to include in their mediums. A book can’t hide a passage in the middle of a chapter; at best they can tack on a clumsy footnote. The act of stumbling on something in a video game, to engage in it purely through the player’s own creative drive, is an incredible feeling. The walkthrough obviously nullifies this organic element of play entirely. But it also makes the inorganic, straight experience possible. Ultimately, the question becomes: Is that sense of discovery worth the hours of non-discovery that goes with it? It’s a different equation for every person, based on their interest in the game and their lives outside it. But it seems likely that a vast majority of non-guide users never even started the Rachel quest, let alone finished it. And that’s a shame.

It’s also, sadly, one of the game’s few justifications. Combat is simple and repetitive, stripped down from the top-down, all-directions Zelda form of combat in Secret of Mana to a belt-scroller side view, complete with combo-chain button mashing. It’s not terrible — it gets the job done, and the game offers a bunch of extra verbs that don’t really alter the formula much for variety’s sake — but it doesn’t stay interesting for the whole runtime. The music and the art do, and go a long way toward explaining what nostalgia Legend does supply.

Ultimately, the appeal of Legend of Mana is the exact converse of its combat skeleton. The game is just weird, in a way that mainstream games aren’t anymore. It makes choices that weren’t evolutionary dead ends, but total head-scratchers even at the time. In many ways, this is Square at the peak of its glorious hubris, swimming in Final Fantasy money, tossing pet projects to everyone. (This game did just fine monetarily, despite the mixed reviews.) It’s the rare AAA game of its time that feels modern, because it’d be a AA game now. Except, you know, without the whole “treating players with abject disdain” part.

Fans of the game around the internet are legitimately split on whether to use a walkthrough, and both arguments are understandable. Opponents argue that it’s something to use for New Game Plus, and that you can’t rewind time: That sense of exploration and randomness that make up so much of the game’s value can only be enjoyed the first time. (“This game is best experienced as a fever dream,” one poster argues.) Proponents counter that it’s a bit of a leap to assume that first time is going to be enjoyable, given the endless ways the game hides mechanics, quests, and even destinations in maze-like dungeons designed to waste the player’s time.

In an ideal world, the solution would be to select the proper guide to fit the demand. For some, that might just be a map with where to place the artifacts to make quests available; for another, it’d be a friendly point toward which zone the player should hunt for their next flag. And for those who don’t have time to flail around, or who are returning to the world for a more complete second pass, the traditional walkthrough can offer more thorough help. Invisiclues, the help system designed for old interactive fiction that seeks to drip-feed hints, are a brilliant invention; they’re also hard to make, and all walkthroughs (outside the Moby strategy guide) are an unpaid labor of love. We have to take what we can get.

Legend of Mana is now available on GamePass, and while the role of streaming game services is its own subject, it might be the ideal way to interact with the series. With no real cost of entry, you can show up in the world of Fa’Diel and leave it again at your own whim, taking as much from the game as you like, in whatever form you like. It’s not a classic, or even a particularly good game by modern standards — your typical seven out of 10, to apply a numerical score to a bigger idea. But chances are that when you think back on it later, remembering the music and the pixel art and the scenery and not the loading screens and backtracking, it’ll feel more like an eight or a nine. Memory is still helping out this series, after all this time.

You just have to know how to leave. Walkthroughs can make an impenetrable game accessible and enjoyable, if only to a limited degree. But those against them are correct about one thing: Legend of Mana should never be played to 100 percent completion. The game, and the series, work best when it leaves you wanting, or at least imagining, so much more.

Patrick Dubuque is currently the Managing Editor of Baseball Prospectus. You can follow him for more of his thoughts and work on Bluesky or Twitter.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter, or donate to my Ko-fi to fund future game coverage at Retro XP.

I've often wondered whether to pick up Legend of Mana, but been consistently stymied by the 70% ratings. Funny; I like the way of thinking about games, that some really are best meant to be played by people who have too much time on their hands. As adults, that sadly no longer applies to any of us.

I recently played through Secret of Mana 1 and most of the way through Secret of Mana 2 on the Collection of Mana for Switch. I had played the first as a child and enjoyed it, and I still think the first game works on its own merits and I'd gently suggest you're being a bit hard on it, though I can't say whether I'd feel the same way if I'd never played it as a kid.

Admittedly, the game feels a bit empty, especially compared to the extraordinarily verbose Final Fantasy games released alongside it – there are very few speaking characters and not much dialogue, and clearly that's a result of its development history. But as a capital-A Adventure game, released the same year as Link's Awakening, it's breathtaking: the art and music are absolutely gorgeous, the character designs are consistently creative. The first time you travel by cannon, you realize that this is a game that will surprise you even if you've played other games in the genre. And from the opening moments of the game, thwacking rabites is deeply satisfying.

(Many like Secret of Mana 2 better; for me, it's more of the same, with some improvements but not much change in formula. Still a very fun game to play.)

The apogee that Squaresoft reached with its pixel art and game music from 1993-1995 remains a high-water mark that award-winning games continue to try to reach. And as flawed Squaresoft games go, I find Secret of Mana *much* more satisfying than Final Fantasy 8, released six years later, whose inventive gameplay is for me totally overwhelmed by a story I found insultingly incoherent.