August 1, 2022 marks the 30th anniversary of the North American debut of Kirby. Throughout the month, I’ll be covering Kirby’s games, creating rankings, and thinking about the past and future of the series. Previous entries in this series can be found through this link.

Nintendo of America has made a lot of weird, inexplicable, and barely defensible choices over the decades, but they were absolutely correct when they told HAL Laboratory that they couldn’t name a game “Twinkle Popo” and expect it to sell outside of Japan. Sure, maybe I would have played it, Mr. Has Written About Multiple Games That Use “Pop’n” and “Twinkle” in their titles, but for the love of God do not market directly to me if you’re trying to sell millions of copies of something.

That game, as you probably surmised from the headline, ended up being called Kirby’s Dream Land, and the Game Boy classic would become HAL’s first million-seller: in fact, it ended up selling over five million copies, and — until 2022’s Kirby and the Forgotten Land likely surpasses it by year’s end — has been the best-selling Kirby game throughout the entirety of the franchise.

The game itself was all HAL’s doing, outside of three things: the name change, which HAL agreed to without fuss because then-president Satoru Iwata had already happily handed off all marketing duties over to the company that had just saved them from bankruptcy after a marketing disaster that sent them spiraling towards it, and the “Extra Mode” that would end up extending the playtime and replayability of Dream Land. The former was Nintendo of America’s idea, as said, but the latter was courtesy Shigeru Miyamoto, a producer on Dream Land, and was only possible due to the third thing: increasing the ROM size to make space for that more difficult version of the game.

Miyamoto, according to Iwata’s posthumous memoir, said that Kirby’s Dream Land “deserved more attention” in the form of tweaks like this, and Sakurai echoed the sentiment by saying that Nintendo felt it would be “a waste” to see the game sell too few copies, so the game was pulled from its pre-order status, where it had logged 20,000 pre-orders to that point, and reworked. The results speak for themselves: a franchise that is now 30 years old, and, for at least a little while longer, a game that is still the best-selling in the series.

The original names for Dream Land and Kirby still live on elsewhere, at least, even if things like the original, less simplistic design for the Popopo character were replaced by the Kirby we ended up seeing. According to The Cutting Room Floor, the very first title for the game was Harukaze Popopo, which translates to something like Popopo of the Spring Breeze. Popopo was Kirby’s original name — Popopo vs. Dedede, look at that — which ended up being used nearly two decades later in Kirby Mass Attack, as the name of the archipelago that the game takes place on. And Spring Breeze is the first available game in SNES classic Kirby Super Star — it’s a 16-bit remake of (most of) Dream Land, with copy powers now included, named as a nod to the series’ origins.

Miyamoto didn’t get his way with everything he wanted out of Kirby, of course. Famously, he thought Kirby was yellow, but Masahiro Sakurai, the creator of Kirby and director of Dream Land, had always envisioned him to be pink. While Kirby was white on the North American box art for Dream Land, Twinkle Popo’s shelved box art featured a pink protagonist:

Admittedly, that’s a deeper shade of pink than what Kirby would end up being after the name change from Popopo, but he’s also very clearly not yellow, nor white. The yellow Kirby that you see as the second option in multiplayer Kirby titles like Dream Course or Amazing Mirror? That’s because Miyamoto’s color preference ended up being the second choice. (The unofficial nickname for yellow Kirby, by the way, is Keeby, which, according to the 20th Anniversary Dream Collection for the Nintendo Wii, is a play on the Japanese word for yellow.)

We have plenty of insight into how the idea for what would become Kirby originated, thanks to the relative openness of both Sakurai and Iwata, who programmed the game even as he was president of HAL, over the years. During a developer interview leading up to the release of Kirby’s Adventure, Sakurai and Iwata both answered the question of “Why did you give Kirby that crazy ability to inhale everything?” (translation courtesy Shmuplations):

Sakurai: I was wondering if I could make a game with simple controls, where you use the enemies to attack. I was thinking of using an enemy the way you’d use a soccer ball: heading the enemy, kicking the enemy…

Iwata: We came up with a lot of ideas, and the one that stuck was “flying.” How would Kirby fly? By puffing up like a balloon! How would he do that? By inhaling the air. Wouldn’t it be fun then, if he could inhale enemies at the same time? …that was the basic thought process.

Using enemies as the weapon with which to defeat other enemies was such a perfect idea for Sakurai’s goal here, which was to create a game that focused on less experienced players, in a genre that was notoriously difficult at the time. It forced players to interact with the foes on screen instead of just attempting to avoid them — especially since the sprites were so much larger in Dream Land than in, say, Super Mario Land, and therefore tougher to avoid — but making them potential weapons who could be inhaled also meant that you were always able to get rid of any foe in front of you without there being too much challenge even for complete newbies. Once you understood the systems in full and could complete the game, you unlocked the Extra Mode, where enemies were faster, more aggressive, and did twice as much damage to Kirby — since you were now well-versed in the rules of Dream Land, though, you were equipped for that scaled-up challenge. As elegant of a system as the marriage of the quoted ideas Sakurai and Iwata discussed.

Source Gaming published a translation of a talk Sakurai gave on the development of Dream Land, in which the director explained that the game was developed with just 512 kilobytes of space, which meant that the team had to be creative to make it all work. Ever wonder why Waddle Doo and Waddle Dee look so similar, outside of their eyes? It’s because making them that way saved space: by using the same torso sprites for two enemies, Kirby’s Dream Land got two enemies for the storage price of 1.5. The spiky enemy, Gordo, was made by “flipping the upper left quarter of its body to the other quarters.” It also made the relatively simple version of Kirby, which existed as a prototype and temporary drawing in Sakurai’s earliest proposal for the game, useful for space-saving purposes.

In addition, from that same talk cited above:

[Sakurai] also thought, “space permitting, I’d like the bosses to be really big.” For example, the bomb-throwing midboss, Poppy Bros. Sr, has only three frames of animation for his feet movement, and two frames for his head. Many such techniques were employed to save as much space as possible. The series regular, Whispy Woods had 3 moving parts– two eyes and the mouth– but each is actually made from the same, single image, which itself is one image rotated across its horizontal axis. King Dedede only appears in his unique boss room, so there was no need to consider the appearance of other characters, because of this, King Dedede used up the most space of any enemy in the game.

Kirby’s Dream Land was made with 512KB of space — Forgotten Land is 6.2 gigabytes. A lot’s changed in 30 years, and it’s not to say that there are no constraints on development now, because there certainly are, but yeah.

There are two other points from the development of Dream Land that feel worth mentioning here. One, Sakurai developed the game without a physical keyboard, as he made it using a trackball and an on-screen keyboard on the Famicom Twin, which was a combo unit that utilized both the Famicom and its Disk System in one place. Sakurai, just 20 at the time and newer to the industry, apparently just thought this was how you were supposed to do things, so he went with it. He described the process as “like using a lunchbox to make lunch,” which is a line I think I need to steal for everyday use.

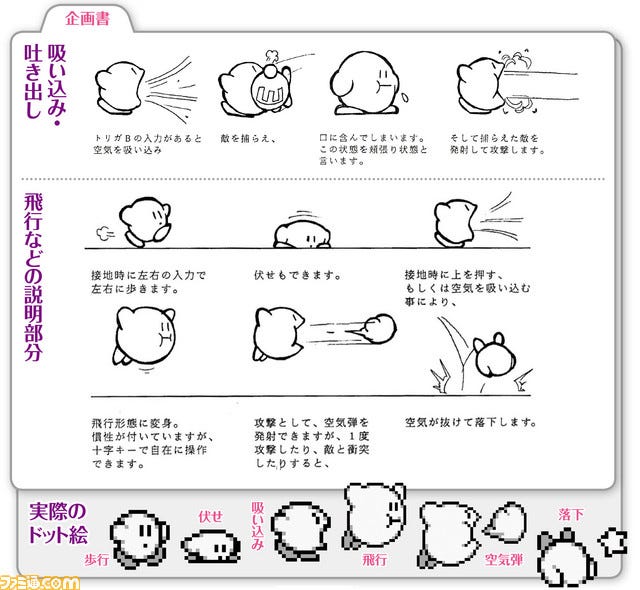

The other is that Sakurai actually came up with one of the key concepts of Smash Bros. during the development of Kirby, but ended up not utilizing it, and then subsequently forgetting about it before inventing it a second time while developing for the Nintendo 64. In Sakurai’s original pitch document, there are images of Kirby taking damage, ricocheting around, and going flying off the screen when he dies, as part of a “cumulative damage system”:

Sakurai would explain that, “To be honest, by the time we made Super Smash Bros., I had forgotten that it was a system I had thought about before, but each of us came up with the same solution for different reasons. In [Dream Land], it was described as a system that takes advantage of the Game Boy's narrow screen.” Why it was cut goes unexplained, but still. Neat, and a more productive use of a shelved idea than a simple nod to a name in a later game, since it helped to launch, no pun intended, an even more successful franchise than the one it originated in.

As for the game itself, it’s as simple as Sakurai intended it to be, and successfully so. Kirby is, outside of the fact that copy abilities hadn’t been introduced to the series yet, the same in 1992 as he is in 2022. He runs, he jumps, he inhales, he floats, he fires off projectiles he had previously swallowed. You will recognize nearly every enemy in the game even if you’ve only played modern Kirby titles, with the only “confusing” part being that Dedede, for once, isn’t brainwashed, but is actually the antagonist of his own volition. It’s an easy game, sure, but that doesn’t make it unenjoyable. It’s breezy, but also a game I’ve bothered to replay time and time again for three decades now, including once again to write about it now even if I wasn’t going to focus on the actual game’s content so much. Because it’s still fun to revisit, all this time later: HAL had really found something here, and Nintendo knew it even in its unfinished state.

It’s so foundational, not even just from a gameplay perspective, but also in how it sounds. Jun Ishikawa would compose the soundtrack, and there probably aren’t that many instances of someone absolutely getting things right the first time to the degree that he did here. Three decades have passed since Ishikawa wrote the soundtrack for Dream Land, and it all still sounds so very much like Kirby today. Part of that is because Ishikawa is still heavily involved in Kirby’s composing, and has been for the entirety of the series’ existence, but it’s also because Kirby’s sound was a success from day one.

The soundtrack showed off what this 8-bit monochrome brick was capable of — the music is, as Kirby music so often would be on more powerful hardware, incessant, with constant notes and layers to it, despite being on such low-level hardware. It’s as impressive as it is catchy, which is why the sound and style stuck the way it did even as Kirby “graduated” to consoles and eventually the 16-bit era’s hardware, too.

There have been so many arrangements of the tracks from Dream Land for a reason, and it’s because they were done so thoughtfully and so completely even on this comparatively limited hardware that they hold up brilliantly all this time later, not just because they elicit feelings of nostalgia in listeners who have been there from the start. Listen to how much is going on in Green Greens, the music for the first stage that would basically become Kirby’s personal theme and used as a basis for plenty of other arrangements and outright new songs in the series over the years:

And Dedede’s theme, too, has survived over the years: Nintendo did a better job with the Game Boy sound than that of the NES, since gameplay and song could work in harmony better on the handheld released a few years later:

It’s all just excellent work, and kind of shocking how much of what is a very short soundtrack for a very short game manages to stick inside your head all these years later.

There are better Kirby games than Dream Land, even if this one has been king of sales for three decades now, but the original still holds up well because it’s just a damn good game. It’s short, yes, it’s simple, obviously, especially since it predates what is considered the core mechanic of the series. But there was something here worth giving more attention to, as Miyamoto put it, something that’s still worth your attention decades later, and it’s really no wonder that the central figures involved in its creation all became household names in the industry, attached to some of the most beloved franchises going.

This newsletter is free for anyone to read, but if you’d like to support my ability to continue writing, you can become a Patreon supporter.